America is often characterized as a nation of immigrants. That makes New Jersey America on steroids.

By Mark Stewart

As much as any state in the nation over the past three-plus centuries, New Jersey has been defined culturally, socially, politically and economically by its newcomers. Decade after decade, our stunning diversity has supplied vital muscle and spirit to the state’s industrial, intellectual and artistic progress. Granted, things haven’t always gone smoothly—it is something of an American tradition to dump on the people who arrived in the U.S. right after you—but by and large, New Jersey has done a sensational job of absorbing its newcomers and leveraging their strengths.

For all its faults and inefficiencies, the odd collection of 500-plus towns and cities that make up the Garden State has enabled every group of newcomers to gain an initial foothold and quickly begin to realize their potential. If anything, that is more true today than at any other time in our history—including the historic mass migration during the late-1800s and early-1900s.

Who are we? How did we get here? In order to know where we are going, it’s helpful to understand where we’ve been.

COLONIAL TIMES

New Jersey at the dawn of the Colonial Era was home to Dutch and Norwegian settlers. In 1638, Swedish and Finnish farmers began carving out space on both sides of the Delaware River, calling their settlement New Sweden. These were hardly gentleman farmers—many, in fact, had been banished from their homelands, with some presented with a choice between exile and the gallows. The Dutch focused their energies along the Hudson River, but their initial attempts at establishing settlements across the water from New Amsterdam (aka Manhattan), were thwarted by hostile natives. Not until 1660 did Dutch farmers gain a permanent foothold in New Jersey, on a rise between the Hudson and Hackensack Rivers in present-day Jersey City.

Upper Case Editorial

By then, the Dutch were no longer calling the shots. In 1644, a quartet of English warships sailed into New York harbor and wrested control from the Dutch. It was a bloodless takeover; the Dutch were traders not warriors and were content to continue plying their trade under a British flag. As every New Jersey school kid learns (but you probably forgot), the crown transferred ownership to George Carteret and John Berkeley (above). They in turn sold off chunks of land and issued the Concessions of Agreement, which included an elected assembly, unfettered trade and freedom of religion (as long as the religion was Protestant).

Upper Case Editorial

The relative freedom afforded by the Concessions of Agreement produced the desired effect: Settlers began pouring into the provinces of East Jersey and West Jersey, as the colony was known. Interestingly, the vast majority of newcomers were not from across the Atlantic, but from New England and Long Island, where the rules regarding government and religion were more constrictive. In 1664, Long Islanders established Elizabethtown and in 1664 refugees from Connecticut founded Newark. In the west, William Penn and the Quakers, who were persecuted in England, settled in Burlington. In New Jersey’s interior, Dutch settlers from the Hudson Valley built vast farms, worked by indentured servants and African slaves. For nearly a century, visitors to New Jersey were more likely to hear Dutch spoken than English.

In 1702, East and West Jersey became New Jersey. The population at that time was around 15,000, with 10,000 people living in the eastern portion of the colony. By the time of the American Revolution, New Jersey’s population exploded, increasing more than tenfold. The boom was a combination of factors. People continued to migrate south from New England and New York. The colony’s fertile soil and plentiful resources triggered a spike in the birth rate. And transatlantic immigration had begun in full force. Scots-Irish (Protestants from Ireland whose recent ancestors had moved from Scotland) and Germans were the two biggest groups. Most of the German settlers continued on to Pennsylvania, where they maintained their culture as the “Pennsylvania Dutch” (Deutsch is actually the word—they aren’t Dutch at all).

EARLY STATEHOOD

At the conclusion of the 18th century, at the dawn of its statehood, roughly seven in 10 New Jerseyans traced their heritage back to the British Isles, with the rest split between Dutch and Germans. Those demographics would change over the next century, but not as rapidly as one might assume. Although America in the early 1800s was a magnet for immigration. New Jersey’s population growth between 1790 and 1840 actually lagged behind neighboring states. Indeed, thousands of newcomers bypassed New Jersey and struck out for more promising farmland along the expanding frontier; most of the prime farmland in New Jersey was already under cultivation. New York and Philadelphia also attracted immigrants who might have settled in New Jersey. In addition, countless New Jerseyans seeking entrepreneurial opportunities during this period moved from rural areas to these major cities.

Even so, New Jersey’s population more than doubled between the Revolution and Civil War. A very high percentage of that increase was “natural” or “internal”—the result of established, growing families. This contributed to a curious dynamic: People in New Jersey began to think of themselves as “native” Americans instead of transplanted Europeans. Unfortunately, his would make life extremely difficult for the next group of immigrants from across the Atlantic.

Economic and political shifts in Europe during the Industrial Revolution drove many people to the United States in the mid-1800s. Those coming from England and Germany tended to be skilled and, often, educated workers who found immediate employment in New Jersey’s growing cities. The outlook for Irish immigrants arriving in America was not as bright. They tended to be unskilled laborers or tenant farmers driven overseas by starvation after a potato blight wiped out their primary source of food in the 1840s. They arrived penniless and unwanted.

Library of Congress

New Irish immigrants often lived in urban squalor, with nearly two-thirds qualifying by modern terminology as “working poor.” Irish men found work only as day laborers. Women between adolescence and marriage fared better as domestic help, and were often the primary breadwinners for their families. This was especially true in New Jersey, where the Irish made up fully half of the state’s new immigrants in the mid-1800s. The impact of the Irish and other new New Jerseyans was profound. They fueled the rapid growth of the state’s industrial centers and swelled the population, particularly in Hudson, Essex and Passaic Counties.

The contributions of New Jersey’s 19th century immigrants went largely unrecognized at the time. America the Melting Pot may have been celebrated as a

www.istockphoto.com

model to the world in the 20th century. In the 19th century, however, few saw the value of a diverse society. In New Jersey, those who viewed themselves as “native born” controlled politics and business, and they wielded this power mercilessly. They also looked down on the state’s new arrivals for the way they enjoyed the country’s promise of freedom of religion. American Protestants in the early 1800s were extremely conservative. In New Jersey, they frowned upon the newcomers’ Sunday activities. After a 60-hour workweek, Europeans were not inclined to devote their off-day to quiet, dignified reflection. They wanted to have fun, picnic, play sports. They overran parks and public spaces, drawing the ire of Protestant groups.

The Irish suffered doubly for their Catholicism. Their loyalty to the United States was constantly questioned because of their fealty to the Pope. Also, a general distrust of Catholicism as being anti-democratic was pervasive in America at this time. The curriculum of New Jersey’s public schools in the pre-Civil War era tilted heavily toward Protestant teaching, to the point where some educators hoped to convert Catholic children. Not surprisingly, it was around this time when Catholic schools began popping up all over the state. Catholic families pulled their kids out of the public schools and also demanded that the state fund these parochial institutions with their tax dollars. Friction between Protestants and Catholics occasionally erupted into violence in New Jersey’s cities. In Newark, a procession of Irish Protestant societies marched into an Irish Catholic neighborhood and a full-fledged riot ensued.

One thing that Irish immigrants brought from their homeland that served them well was their ability to organize against an oppressor. In Ireland, they defied British rule. In American cities, as Irish populations swelled (and created huge voting blocks) their leaders found opportunities in controlling local politics and, by extension, exerting their influence on labor organizations and municipal jobs, including police forces. By the end of the 1800s, their children and children’s children would come to think of themselves as the native New Jerseyans, but in a different way. Although the Irish were no longer newcomers, they remained keenly aware of the distinct aspects of their culture, and proud of them. Each immigrant group that subsequently arrived in the Garden State followed their example, contributing to New Jersey’s diverse cultural tableau.

THE FLOODGATES OPEN

The final decades of the 19th century saw an astonishing uptick in immigration. Greater stability in Western Europe stemmed the tide from England, Ireland and Germany. Now the “new” immigrants came from Eastern and Southern Europe—primarily Italy, Poland, Russia and Hungary. They were characterized as the dregs of Europe: unsophisticated, uneducated and incapable of contributing to a society where they didn’t even speak the language. The reality, of course, was far different. The so-called “great unwashed” and “huddled masses” actually tended to be young, healthy and ambitious. Many young men came to America alone, hoping to secure jobs that would enable them to bring their families over, or at least return home with money in their pockets. These immigrants ended up propelling the Industrial Revolution in the U.S. to new heights with their minds and bodies, contributing to a wide array of industries and making game-changing contributions to science and the arts.

Between 1880 and 1930, thanks largely to the inflow of European immigrants, New Jersey’s population nearly quadrupled, from just over one million to four million. Jersey City, Camden, Trenton and Newark became thriving urban centers during this time, while cities such as Paterson, Passaic and Elizabeth reached the height of their commercial power. The consumer culture that blossomed in America in the early 1900s was no more evident than in Newark, where retail space on Market and Broad Streets fetched higher rents than on Fifth Avenue in New York City. Tunnels, bridges and modern ports, built by recent immigrants—along with the children and grandchildren of immigrants—provided vital links to the rest of the country.

The experience of New Jersey’s first Italian immigrants differed somewhat from that of the Irish. It’s worth noting because today the number of New Jerseyans who claim Italian or Irish heritage is roughly equal. (The exact figures depend on who’s doing the counting, and what criteria they employ, but from a purely empirical standpoint it seems about right.) Thousands of Italian immigrants found employment in New Jersey’s agricultural sector. In South Jersey, near the Pinelands, where the land can be extremely uncooperative, Italian farmers—renowned for their ability to coax produce from sketchy soil—were actively recruited from remote villages. Agents sent to Southern Italy and Sicily by New Jersey land investors posted bills that promised free passage and 20 acres of land for strong men willing to farm their plots. Grapes grew particularly well in the area, which was eventually renamed Vineland.

Most Italian immigrants to New Jersey settled in its urban areas, arriving in especially large numbers in the first two decades of the 20th century. In many cases, they “replaced” the Irish as the go-to day laborers, particularly in railroad and housing construction. Italian women, as a rule, did not work outside the home as domestics. They were more likely to contribute financially by doing piecework out of their homes. Few Italians spoke English when they arrived. They dealt with this disadvantage by establishing self-sufficient neighborhoods in cities like Newark, where Italian was the common tongue in the First Ward for decades. Within these neighborhoods were clusters of Italian families from specific villages, with their own patron saints and annual festivals.

Immigrants from Eastern Europe often gravitated to the cities of Passaic and Paterson. At the turn of the 20th century they were home to dozens of enormous textile operations. Laborers from Russia, Poland and Hungary found steady employment in these businesses. They were paid poorly by mill owners and lived in crowded, dirty conditions. In 1920, Passaic might have been the nation’s most “foreign” city—85 percent of its population was either born outside the U.S. or were children of immigrants. In the crowded First Ward, only 1 in 100 residents could claim to be a “native” New Jerseyan.

A SENSE OF IDENTITY

Today. we often use terms like Italian-American, Irish-American and German-American out of cultural recognition or sensitivity. A century ago, these terms would actually have been more appropriate. Immigrants arriving in New Jersey did not come to “be Americans.” They came to be Italians in America or Irish in America or German in America. A national identity (in the modern sense) would not be truly galvanized until World War II. Indeed, when World War I began in 1914, New Jersey’s multi-ethnic makeup created some tricky issues. Irish-Americans, for instance, were critical of the U.S. government’s support of England. German-Americans and immigrants from Austria-Hungary tended to root for their countries of origin in the early days of the war. They were not anti-American per se, but their loyalties were certainly divided—particularly in 1914, when it was assumed that the fighting would end soon.

Not surprisingly, once the U.S. was drawn into the war against Germany in 1917, German-Americans in New Jersey found themselves the target of hatred and suspicion. Hundreds were rounded up, often on the slimmest of pretenses, suspected of being saboteurs or enemy agents.

Starting in the 1920s, the federal government put the clamps on mass immigration. What had been a flood became little more than a trickle. Restrictions and quotas during this time tended to favor Northern Europeans. With the exception of refugees following World War II, it was unusual to come across a “recent immigrant” in New Jersey. As a result, what had been distinct cultures slowly became Americanized, with traditions (and family names) handed down to children and grandchildren. By the 1960s, the only people with deep “accents” were probably 50 yeas old or older.

Library of Congress

THE IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY ACT OF 1965

In the last 50 years, the majority of new New Jerseyans have come from Spanish-speaking countries and from Asia. In 1965, Congress passed sweeping immigration reforms that struck down the restrictive quota system that had been in place since the 1920s. The new rules gave preference to people who already had family members residing in the U.S., and to skilled laborers. In the ensuing decades, political upheaval in Latin America and a lack of economic opportunities in Asia sparked an explosion of “kin-based migration chains” from these regions of the world. At the same time, Europe had completed its recovery from World War II, so there was little incentive for Europeans to seek American citizenship. These two demographic trends combined to change the face of America—and particularly New Jersey.

Because of its long history of cultural diversity, its economic opportunities and its proximity to major cities, New Jersey proved to be a particularly popular landing spot for immigrants from Asia and Latin America. The state’s current population of roughly 9 million represents 2.8% of the U.S. population, yet upwards of 6% of the country’s new immigrants settle here. That percentage may be even higher when undocumented individuals are taken into account.

New Jersey’s Asian population grew steadily in the 1970s and 1980s to more than 250,000. From 1990 to 2000 it jumped dramatically, by nearly 100 percent. The largest groups were made up of immigrants from India, followed by China and the Philippines. Today, there are significant Indian populations in the towns of Edison and Iselin, as well as in Jersey City, which has the largest Indian population in the state, estimated at over 25,000. At 10.9% of the city’s total population, it is the most ethnically Indian of any major city in the country. “Little India” along Newark Avenue is home to Hindu temples, Indian restaurants and grocery stores, and the site of numerous celebrations, including the Navratri festival each autumn.

New Jersey’s Korean population is centered around Palisades Park in Bergen County, including the neighboring towns of Fort Lee, Leonia and Tenafly. In the 1970s and 1980s, the first wave of immigrants included a high percentage of famously hardworking but unskilled laborers. Over the last quarter-century, the socioeconomic and educational profile of Korean immigrants to New Jersey has risen dramatically.

There are some really interesting demographics out there on other Asian-American groups in New Jersey, particularly those claiming Chinese and Filipino heritage. However, taking a deep dive into those numbers can be tricky. The last U.S. census was in 2010, so the most accurate statistics on who New Jerseyans are and where they live are a mish-mash of seven-year-old census records and data collected by various studies—some by academics and others by state agencies like the New Jersey Department of Labor. Which is to say they are inherently inaccurate. It will be fascinating to see how rapidly the state’s demographics have shifted when the 2020 census results come out. Much of the data collection will be done via the Internet, which adds an additional wrinkle to the process. What can be said with some certainty at this point about

Photo by LuigiNovi Nightscream

New Jersey’s Asian population is that—

as a percentage of the overall population—it ranks third in the nation behind Hawaii and California.

Americans of Asian descent number roughly 20 million, making up around 6% of the U.S. population. In New Jersey, the percentage is around 10%.

LATINO NEW JERSEY

Historically, the state’s Latino Hispanic communities tend to form in its urban centers. They make up the majority of residents in seven cities of 25,000 or more: Fairview, Paterson, Elizabeth, North Bergen, Dover, Passaic, Perth Amboy, West New York and Union City. In Perth Amboy, West New York and Union City, more than three in four residents is Latino. Although one tends to think of Spanish-speaking communities as heavily immigrant, the fact is that roughly three in five Latinos living in the state were born in the United States.

Starting in the 1950s, New Jersey’s Cuban population—many from Fomento and Villa Clara in central Cuba—coalesced around Union City. The Cuban population spread north and south in the ensuing decades and, today, some call this stretch of waterfront “Havana on the Hudson.” Another New Jersey city that became a landing place for immigrants from a specific country is Paterson, which has seen its Peruvian population grow dramatically. The city’s downtown area has been called “Little Lima” or “Little Peru.” Old-timers recall that this neighborhood had once been nicknamed “Dublin” for its heavy Irish population and the line of mills along the Passaic River—and then “Little Italy,” after another wave of European immigrants arrived. Paterson’s Main Street still boasts a Little Italy section, as well as distinct Dominican, Puerto Rican, and Mexican neighborhoods.

New Jersey’s Mexican population has experienced stunning growth. In little more than a generation (since 1990) it has increased more than 800 percent, from around 30,000 to more than a quarter-million. Overall, the Hispanic population in New Jersey grew by two-and-half times during the same period. Mexicans now represent the second-largest Hispanic population in the state, behind Puerto Ricans and just ahead of Dominicans, who make up the largest group from a Caribbean nation. That being said, New Jersey is home to more than 450,000 people who trace their heritage to Puerto Rico. Only New York and Florida have larger Puerto Rican populations. For most of the 20th century, Puerto Rican communities were concentrated in the urban centers of Hudson and Essex Counties, including Newark, Elizabeth and Jersey City. Large Puerto Communities are now located in Paterson, Camden, Trenton, Vineland and Perth Amboy. Puerto Rican migration to the U.S. began in the 1920s, but it wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s that New Jersey became a popular destination.

Which part of the world will send New Jersey its next “wave” of newcomers? With the world’s climate changing, food stress may serve as the trigger. History teaches us that people are often willing to live in fear of war or violence, but nothing moves populations like the fear of starvation. That makes parts of Africa and the Middle East prime candidates. Alas, once thing is certain: Whoever has the fortitude, ambition and luck to make it to America, they can count on finding a Welcome mat in the Garden State.

JEWS IN NEW JERSEY

Like most newcomers to the state, Jewish immigrants created insulated communities within New Jersey’s cities, specifically Newark, Paterson and Camden. The Weequahic section of Newark—a city that at one time claimed more than 75,000 Jewish residents—was perhaps the state’s most famous. The initial wave of Jewish immigrants were German Jews during the mid-1800s. They were extremely influential in the state’s economic growth. At the turn of the century, Jewish immigrants were more likely to come from Russia, Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe, where they were victims of persecution. In the years after World War II, Jewish families that could afford to move to the Garden State’s rapidly expanding suburbs did so.Today, New Jersey’s Jewish populations are predominantly located in suburbs, as opposed to urban centers or “exurbs.” Today there are approximately 550,000 Jews living in New Jersey. The Ocean County town of Lakewood is home to one of the nation’s largest Orthodox communities, which makes up more than half of Lakewood’s population. Beth Medrash Govoha, one of the world’s most heralded rabbinical colleges, is located in the town.

Like most newcomers to the state, Jewish immigrants created insulated communities within New Jersey’s cities, specifically Newark, Paterson and Camden. The Weequahic section of Newark—a city that at one time claimed more than 75,000 Jewish residents—was perhaps the state’s most famous. The initial wave of Jewish immigrants were German Jews during the mid-1800s. They were extremely influential in the state’s economic growth. At the turn of the century, Jewish immigrants were more likely to come from Russia, Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe, where they were victims of persecution. In the years after World War II, Jewish families that could afford to move to the Garden State’s rapidly expanding suburbs did so.Today, New Jersey’s Jewish populations are predominantly located in suburbs, as opposed to urban centers or “exurbs.” Today there are approximately 550,000 Jews living in New Jersey. The Ocean County town of Lakewood is home to one of the nation’s largest Orthodox communities, which makes up more than half of Lakewood’s population. Beth Medrash Govoha, one of the world’s most heralded rabbinical colleges, is located in the town.

THE BLACK EXPERIENCE

THE BLACK EXPERIENCE

African-Americans were among the earliest settlers in New Jersey, although often they had no say in the matter. They were imported as slave labor from Africa or the West Indies by the Dutch and the English. Perth Amboy and Camden were major ports of entry for the trade. While New Jersey had a significant population of “free blacks” in the 1700s, at the time of the American Revolution there were more than 10,000 slaves in the state. The vast majority labored on farms or in ports, which were New Jersey’s two major industries. That explains why it took the state legislature until 1804 to outlaw slavery—and then only gradually. For decades after, many children born to New Jersey slaves were classified as “apprentices” to the owners of their parents into their 20s and beyond. Not until the 13th Amendment was passed in 1865 were the final 16 African-Americans still serving “apprenticeships” legally free.

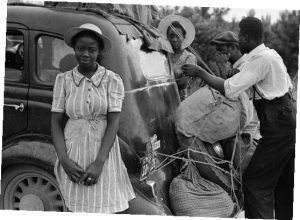

New Jersey’s African-American population did not undergo significant growth until World War I, when demand for industrial laborers in the urbanized North and Midwest triggered the “Great Migration” of more than 1.5 million blacks from the rural South between 1916 and 1930. A second wave estimated at nearly 5 million left the South for the North, West and Midwest in the quarter-century after World War II.

Today, African-Americans make up the majority of residents in six cities of 25,000 or more: Newark, Camden, East Orange, Irvington, Willingboro and Orange. There are also large numbers of African-American families in Jersey City, Trenton, Paterson, Plainfield, Passaic and Lakewood. About 1.2 million people in New Jersey identify themselves as “black” or African-American.