We are producing a bumper crop of athletes in women’s sports in the Garden State. Do we know who planted those seeds?

New Jersey’s official nickname, The Garden State, first became popular during the 1800s, when New York, Philadelphia and other cities grew ever more dependent on the fruit, vegetables and dairy items produced by our famously fertile soil. Today, there is another export crop you can add to the list: top-notch athletes. We grow them like crazy.

This has been true for decades, of course. As noted elsewhere in this issue, New Jersey has a particular set of circumstances—great population density, strong school programs, healthy income and employment numbers, a terrific road system and, let’s be honest, a little bit of a chip on our shoulders—that constantly recombine to produce talented, successful and occasionally transcendent young men and women who leave their indelible stamp on college, international and professional sports. Okay, now let’s be honest again: The guys hogged the sports spotlight for more than a century here. It’s about time the girls get to share it.

Library of Congress

New Jersey’s explosion in women’s sports programs and participation—from grade school on up—is a relatively recent phenomenon. It was triggered in large part by the passing of Title IX legislation in the 1970s. Title IX was indeed a game-changer. It banned discrimination in higher education, which in turn compelled colleges and universities to support (and often create) women’s sports programs. With a dramatic expansion in college sports teams, the trickle-down effect was that coaches needed star athletes…and New Jersey schools and communities were uniquely structured to feed that need. Which is how we arrived at where we are today. However, giving Title IX the lioness’s share of the credit, as some do, misses a critical point: Today’s athletes stand on the shoulders of the pioneers of their sports—most of whom lived and played decades before Title IX, with some stretching back to the turn of the last century.

Country Club Types

The 1890s are sometimes referred to as the Gilded Age in New Jersey. For sports historians, that decade marked the first flowering of women’s sports in the Garden State. The elite-level athletes of that era tended to be children of means, young ladies who watched their male counterparts play country club sports like golf and tennis—and who wanted in on the action. Of course, they were bucking a cultural norm that had existed for centuries, the understanding that girls with the energy and athleticism to excel in sports should simply find another, more “ladylike” outlet for their talents. Consequently, the first stars of women’s sports in New Jersey weren’t concerned with how they might look to a future husband dripping with sweat. They were winners who possessed a killer instinct. And when the door opened a crack, they simply powered through it.

Pure Golf Auctions

The groundbreakers in tennis included Aline Terry of Princeton, who won the 1893 U.S. singles and doubles championships, and Bessie Moore (right) of Ridgewood, who won a total of six U.S. titles between 1896 and 1905. Terry was a highly mobile and stunningly aggressive player, despite the fact she played at a time when women were expected to wear ankle-length tennis dresses. Moore won by outlasting opponents in long rallies, thanks to her equally good forehand and backhand. She reached her first U.S. singles titles at the age of 16 and, at age 31, was the first-ever U.S. Indoors champion, winning the inaugural tournament held in New York’s Park Avenue Armory. Moore’s great rival was Juliette Atkinson, who was born in Rahway but learned the game growing up in Brooklyn (we’ll take some credit for her as a Jersey Girl anyway). Atkinson combined stamina and strategy to become the nation’s top player in the late-1890s.

Another top player in the early days of tennis was Helen Homans. Growing up in Englewood, she sharpened her skills playing against her older brother, Shep, when she was a young teenager and he was an All-American football star at Princeton (and later a champion tennis player). Homans won the 1905 U.S. singles champion-ship and was a supremely talented doubles player. She married her frequent mixed doubles partner, Marshall McLean, and played at a high level well into her 50s.

Top-flight women’s golf also got its start in the 1890s. For several years before that, New Jersey country clubs set aside certain days for their female members and created a set of tees that were closest to the hole for beginners, juniors and women (though to this day they are somewhat derogatorily known as “ladies” tees). The U.S. Women’s Amateur Championship, which is the country’s third-oldest golf tournament, began in 1895 and was held at the Morris County Golf Club in its second year, 1896. The club had been in operation only two years at that point, having been formed as America’s first all-women golf club in 1894. In 1897, the competition moved to the Essex County Country Club in West Orange. Beatrix Hoyt, the granddaughter of Salmon P. Chase—who served as Secretary of the Treasury and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court during the Abraham Lincoln administration—won both tournaments.

Upper Case Editorial

The biggest name in women’s golf in New Jersey during the 1920s and 1930s was Maureen Orcutt (below), who learned the game as a girl in Englewood. She was runner-up at the U.S. Women’s Amateur in 1927 and won more than 50 titles during her career, including the U.S. Senior crown twice in the 1960s. Orcutt became just the second female sports-writer for The New York Times. In 1946, the former Olympic track star Babe Didrikson Zaharias helped women’s professional golf get off the ground by founding the LPGA Tour. The U.S. Women’s Open came to New Jersey for the first time in 1948 and Babe, age 37, cruised to the title by eight strokes. The tournament returned to New Jersey five more times between 1961 and 2017.

Run Camille Run

While golf and tennis were dominated by the upper crust in New Jersey during the early 20th century, other sports enabled elite athletes to show their stuff regardless of how well-off their families were. The first dual track meet for female athletes was held in 1903 in Montclair and Spalding’s annual guide listed women’s track and field records for the first time in 1904. As social attitudes changed about the value of vigorous exercise for young women, running, jumping and throwing competition became commonplace in New Jersey high schools during the first two decades of the 1900s (although male spectators were often barred from these events).

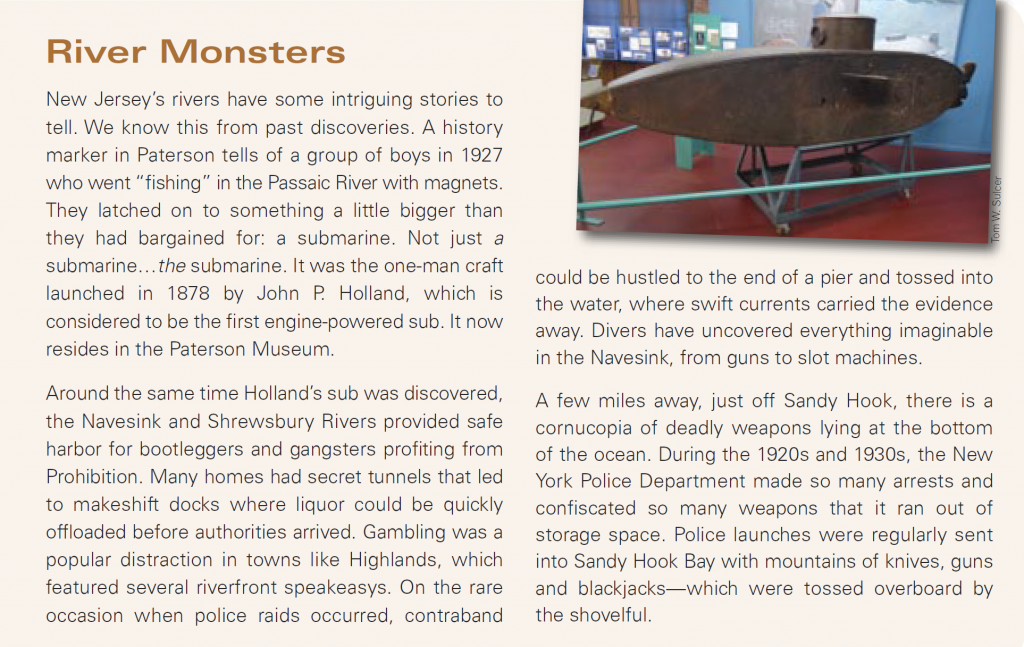

The 1920s are called the Golden Age of Sports in America and that was certainly true in New Jersey. Women’s softball teams began springing up across the state and bowling became a popular women’s sport after Prohibition kicked in. Prior to that, bowling alleys were allowed to serve alcohol and were basically sports bars for men. When the taps were shut off, bowling alleys courted women to make up for lost income. Competitive swimming also became a popular sport for women, especially along the Jersey Shore. Gertrude Ederle (above), who summered in Highlands, learned to fight off the strong currents of Sandy Hook Bay and developed the endurance she needed to become the first woman to swim the English Channel, in 1926.

Black Book Partners

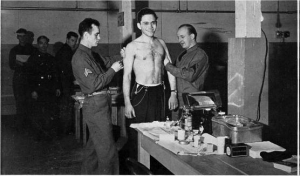

For nearly two decades prior to the Second World War, New Jersey became a regional hub for men’s and women’s track and field events. The first great homegrown women’s star was Camille Sabie (above), a teen prodigy whose name has, unfortunately, been lost to history. Sabie, a Newark girl, was so explosive in short sprints and hurdles that officials sometimes wondered if there was something wrong with their stopwatches. In 1922, she shattered the world record in the 100-yard hurdles twice in two different meets on back-to-back days. She was picked to compete on America’s first international track team, in Paris, where she broke her own world record twice more, ran the anchor leg for the 440 relay squad and beat all comers in the broad jump. In the fall of 1922, she continued smashing records. At a meet in Newark’s Weequahic Park, 25,000 people showed up to watch her equal the American record in the 100-yard dash and set new world records in the broad jump and 60-yard hurdles. Sabie retired from competition shortly before her 20th birthday and eventually became the beloved Phys. Ed. Teacher at her alma mater, East Side High School in Newark.

In 1923, Newark was selected as the site of the first Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) women’s track and field championships. The meet was won by a team sponsored by Prudential Insurance. In 1931, the AAU championships were held in Newark again and, by the time they were done, a 19-year-old Texan had become a household name. Babe Didrikson (yes, the same “Babe” who would help establish the LPGA 15 years later) won the long jump, broke the U.S. record in the hurdles and won the baseball throw with a distance of 296 feet—a record that apparently still stands. Didrikson’s time in the hurdles was so good that officials held up the meet to measure the track…and found that it was actually more than two feet too long.

Another early New Jersey track star was Paterson’s Eleanor Egg, a sprinter who piled up more than 250 medals and trophies in the 1920s and ’30s—but missed two Olympics due to unfortunately timed injuries. Mae Faggs, the first American woman to compete in three Olympics (1948, ’52 and ’56), was born in Mays Landing and grew up in Queens. Another transplanted New Jersey Olympian was Mary Decker-Slaney, who spent her early years in Hunterdon County before moving to the West Coast in the late-1960s.

New Jersey Gems

Over the ensuing decades, Garden State high schools sent several track and field athletes to top college programs—a process that accelerated dramatically after Title IX legislation was passed. That paved the way for New Jersey Olympians like Joetta Clark of South Orange—who represented the U.S. in four Olympics—and her younger sister, Hazel. At the 2000 Olympic trials, Joetta, Hazel and sister-in-law Jearl Miles-Clark swept the top three spots in the 800 meters final—an all-sisters outcome we are unlikely to see again in any track event. This past summer, Sydney McLaughlin of Dunellen was the talk of the Olympics, setting a new world record in the 400-meter hurdles and also winning gold as a member of the 4 x 400 relay team. All are part of a continuum that stretches back nearly a century to the triumphs of Camille Sabie.

Playing Ball

The breakout sports stars of the 1920s and 1930s laid the foundation for the postwar boom in New Jersey of girls’ and women’s sports participation. Softball, swimming and basketball in particular took off. As mentioned earlier, softball was being played at a high level in the Garden State prior to the war years, particularly in Bergen and Hudson counties. In fact, several players in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (made famous in A League of Their Own) came from New Jersey, most notably Dolores Lee of Jersey City, who inspired the scene where Rosie O’Donnell throws two baseballs at the same time. After the AAGPL folded in the mid-1950s, several top stars joined the New Jersey-based Allington All-Stars, a barnstorming club that took on men’s teams all over the country. Their star was Dottie Schroeder, who was played by Gina Davis in the movie. A generation later, girls were getting in on Little League action, starting with Maria Pepe, whose insistence on playing for her Hoboken team in 1972 opened the door to millions of girls who followed.

NJSports.com

Women’s hoops picked up steam in the 1950s and 1960s with the international success of AAU teams and became a full-blown phenomenon in New Jersey during the 1970s, thanks to a confluence of forces: the announcement that women’s basketball would become an Olympic sport in 1976, the advent of Title IX, and the wondrous play of Carol Blazejowski (above). Blazejowski starred for Cranford High and then Montclair College, where she drew huge crowds not only at Montclair but also at Madison Square Garden. She later starred for the New Jersey Gems in the short-lived Women’s Professional Basketball League. Sports Illustrated called her the most relentlessly exciting performer in the history of women’s basketball. One of the co-captains of the aforementioned ’76 Olympic team was Juliene Brazinski Simpson, who developed her skills as a point guard competing against the guys on the playgrounds of Elizabeth and later, in high school, for Benedictine Academy.

One of the early pioneers of women’s basketball was Cathy Cowan of Egg Harbor. She attended West Chester College south of Philadelphia, which had a strong athletic program for women, and ended up being one of the top coaches in the nation during the 1970s. She married NBA referee Ed Rush and later ran basketball camps for girls. One of her counselors was Geno Auriemma, who went on to win multiple NCAA titles as head coach of the UConn Huskies. Another camp counselor was Cheryl Reeve of Washington Township, who coached the Minnesota Lynx to the WNBA title in 2011. The first president of the WNBA, it’s worth noting, was Val Ackerman of Pennington, who starred in college for the University of Virginia. By the 1980s, New Jersey was producing some of the nation’s top players, including Valerie Still of Camden, Adrienne Goodson of Bayonne and Anne Donovan of Ridgewood. Donovan won Olympic gold in 1984 and 1988 as a player, and then as head coach of Team USA in 2008. She also led the Seattle Storm to the WNBA championship in 2004.

New Jersey women began making waves in aquatic sports starting in the 1960s. Lesley Bush, who attended a school in Princeton without a swimming or diving team, found a home at a training center an hour north in Mountain Lakes and made the Olympic diving team in 1964 at age 16. When she stunned the experts by winning gold in Tokyo as a relative unknown in the platform competition, even her parents thought it might be a mistake. Princeton threw a parade for Bush upon her return and many of her classmates—who were let out of school for the day—had no idea it was that Lesley Bush they were going to see. Another teenage swimming prodigy was Ginny Duenkel (right) of West Orange, who also won gold at the 1964 Olympics. Neither her parents nor her coach could afford the airfare to Japan, so she went alone and demolished the world record in the 400-meter freestyle. An earlier gold medalist was Joan Spillane, who began her swimming career in Glen Ridge before moving to Houston. She was a member of the record-setting 1960 freestyle relay team. These swimmers set the stage for modern record-breakers and NCAA champions, including Olympic gold medalists Kelsi Worrell of Westampton Township and Rebecca Soni of Plainsboro.

Gymnastics Hall of Fame

In recent years, gymnastics has made its share of headlines in Garden State newspapers, and there are dozens of first-rate gyms here to get young girls started in the sport. Laurie Hernandez of Old Bridge had something to do with that. She surprised many experts when she finished second behind Simone Biles at the 2016 Olympic Trials, and then won silver in Rio on the balance beam (with Biles taking the bronze). Hernandez also helped the American team win the all-around, becoming the first person born in the 21st century to win Olympic gold. She was the latest star in a Garden State gymnastics tradition that stretched back to the Swiss and German turnvereins of the early 1900s. Along the way, New Jersey produced several elite-level gymnasts, including Irma “Chip” Haubold of Union City (a 1936 Olympian along with her husband, Frank) Helen Schifano of East Orange—America’s top competitor during the 1940s—Roxanne Pierce (right) of Springfield, Alyssa Beckerman of Middletown and Kristen Maloney, who began her career in Hackettstown before moving to Pennsylvania.

There is seemingly no end to the sports that have been impacted by New Jersey women on the national and international levels. They include figure skating, skiing, hockey, cycling, rowing, fencing, bowling, lacrosse, field hockey, all manner of equestrian sports and even professional wrestling. Unfortunately, magazines being what they are, there is only so much one can squeeze in so many pages. The question of who sowed the seeds of women’s sports culture in New Jersey is one that deserves deeper dives and a much more comprehensive answer.

Honestly, you could write a book about it.

account is empty. According to the critics of Artificial Intelligence—including the geniuses who created it—this is one version of the dark future that supposedly awaits us if we don’t get a handle on AI.

account is empty. According to the critics of Artificial Intelligence—including the geniuses who created it—this is one version of the dark future that supposedly awaits us if we don’t get a handle on AI.

assistant could not only read bedtime stories, but could customize those stories for each child, embracing favorite themes or reinforcing lessons learned that day. The same device would also be smart enough to shield a child from inappropriate content, and weigh in on concepts such as good and bad and right and wrong. Parents would be able to control an AI assistant and set all kinds of parameters to ensure that their offspring grow up with the educational and cultural guardrails they choose. For tweens and teens, a trusted AI assistant could be helpful working through issues of social anxiety and depression.

assistant could not only read bedtime stories, but could customize those stories for each child, embracing favorite themes or reinforcing lessons learned that day. The same device would also be smart enough to shield a child from inappropriate content, and weigh in on concepts such as good and bad and right and wrong. Parents would be able to control an AI assistant and set all kinds of parameters to ensure that their offspring grow up with the educational and cultural guardrails they choose. For tweens and teens, a trusted AI assistant could be helpful working through issues of social anxiety and depression.

Getting Help

Getting Help  During the pandemic, the Institute continued to serve clients through Zoom sessions. Despite an adjustment period, therapy quality was never compromised. Some clients (especially those living at a distance from Trinitas) found teletherapy to their liking, while others rejoiced when in-person therapy resumed. Most importantly, all of the DBT clients continued to make progress in the face of heightened stress and anxiety.

During the pandemic, the Institute continued to serve clients through Zoom sessions. Despite an adjustment period, therapy quality was never compromised. Some clients (especially those living at a distance from Trinitas) found teletherapy to their liking, while others rejoiced when in-person therapy resumed. Most importantly, all of the DBT clients continued to make progress in the face of heightened stress and anxiety. Modifying ingrained behavior patterns requires a whole-hearted dedication to achieving a balance between emotional extremes and learning how to identify and make more effective choices. Before being accepted, the DBT team spends time screening prospective clients on the telephone, followed by personal interviews to discern levels of motivation, increase commitment, troubleshoot potential issues and agree on a collaborative approach to reaching goals. The DBT program provides the tools and encouragement; the commitment to apply them to daily life is up to the client.

Modifying ingrained behavior patterns requires a whole-hearted dedication to achieving a balance between emotional extremes and learning how to identify and make more effective choices. Before being accepted, the DBT team spends time screening prospective clients on the telephone, followed by personal interviews to discern levels of motivation, increase commitment, troubleshoot potential issues and agree on a collaborative approach to reaching goals. The DBT program provides the tools and encouragement; the commitment to apply them to daily life is up to the client.

academics pondering why attributes such as resilience have dwindled in recent decades. Dr. Richard Weissbourd, a Harvard professor, is also concerned about the priorities of parenting youth in America today. He calls upon parents to reflect upon the emphasis on their children’s happiness, self-esteem and achievement to the extent that these concerns appear to have usurped the importance of more character-driven values. Weissbourd goes on to say that American parents today are so concerned with their children’s achievement and happiness, that they shelter and hover—so much so that they attempt to envelop them in a stifling bubblewrap hug of insulation.

academics pondering why attributes such as resilience have dwindled in recent decades. Dr. Richard Weissbourd, a Harvard professor, is also concerned about the priorities of parenting youth in America today. He calls upon parents to reflect upon the emphasis on their children’s happiness, self-esteem and achievement to the extent that these concerns appear to have usurped the importance of more character-driven values. Weissbourd goes on to say that American parents today are so concerned with their children’s achievement and happiness, that they shelter and hover—so much so that they attempt to envelop them in a stifling bubblewrap hug of insulation.

A LITTLE HISTORY Gaming wasn’t much of an issue when it began in the 1970s. In fact, the word gaming itself did not yet exist. Pong and Space Invaders could be found in arcades and bars, fascinating the quarter-pushers, but the appeal proved limited. However, a new culture had been born. Indeed, 10 years later, Nintendo consoles were everywhere, and games like Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros., Zelda, and Metroid had parents enforcing strict bedtimes for their prepubescent offspring. The video game industry continued to grow, technologically and financially, as it entered the 21st century. With the doubling of computer power every few years, games had become more complex, more sophisticated and more addictive. And the money being spent on video games by the public was absolutely staggering. Grand Theft Auto IV was released in 2008 and sold six million units, grossing $500 million, in its first week of release. Game developers, now working with squads of brilliant artists, writers, and coders, had tapped into a demand that would have been unimaginable just a few years earlier. Games were modified to be playable not only on hot-selling consoles like Xbox and PlayStation, but on home computers, laptops, tablets and, inevitably, smartphones. With these remarkable advances came a backlash. The assaults came from many quarters—gaming was blamed for teen violence, plummeting verbal abilities, rampaging obesity, and plagues of ADHD, autism and pathological solipsism. College grads, who “should have been” out looking for jobs and spouses, were locking themselves in their darkened rooms with enormous supplies of tortilla chips and diet soda, playing everything from the latest John Madden NFL (total sales for the series estimated at $3 billion) to Guitar Hero, Tiger Woods Golf or Call of Duty.

A LITTLE HISTORY Gaming wasn’t much of an issue when it began in the 1970s. In fact, the word gaming itself did not yet exist. Pong and Space Invaders could be found in arcades and bars, fascinating the quarter-pushers, but the appeal proved limited. However, a new culture had been born. Indeed, 10 years later, Nintendo consoles were everywhere, and games like Donkey Kong, Super Mario Bros., Zelda, and Metroid had parents enforcing strict bedtimes for their prepubescent offspring. The video game industry continued to grow, technologically and financially, as it entered the 21st century. With the doubling of computer power every few years, games had become more complex, more sophisticated and more addictive. And the money being spent on video games by the public was absolutely staggering. Grand Theft Auto IV was released in 2008 and sold six million units, grossing $500 million, in its first week of release. Game developers, now working with squads of brilliant artists, writers, and coders, had tapped into a demand that would have been unimaginable just a few years earlier. Games were modified to be playable not only on hot-selling consoles like Xbox and PlayStation, but on home computers, laptops, tablets and, inevitably, smartphones. With these remarkable advances came a backlash. The assaults came from many quarters—gaming was blamed for teen violence, plummeting verbal abilities, rampaging obesity, and plagues of ADHD, autism and pathological solipsism. College grads, who “should have been” out looking for jobs and spouses, were locking themselves in their darkened rooms with enormous supplies of tortilla chips and diet soda, playing everything from the latest John Madden NFL (total sales for the series estimated at $3 billion) to Guitar Hero, Tiger Woods Golf or Call of Duty.

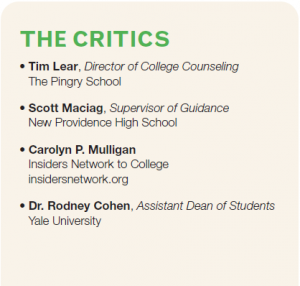

maintains that the subject matter was potentially risky, as some colleges might view the author as “a rather spoiled, a suburban poet without any real wisdom to impart.” “While good writing is good writing, period,” Lear explains, “students need to tell a good story and try to exhibit some real depth. Introspection is an underrated trait, and students are often quick to wrap up their essays too simply or neatly. Embracing ambiguity and thinking deeply before writing are two tips I would offer seniors.” “I thought it was well written, but it ultimately left me scratching my head,” says Cohen, who wanted to know more about the student than was revealed in the essay. “It didn’t tell me enough about the writer as a person. He/she spent entirely too much time on the accident. Ultimately schools are looking for Who are you? How are you going to fit in?” “I like the line about the ‘grave consequences await both my actions and inactions,’’ says Maciag. “This line can send a powerful message. I feel a more substantive essay could have come out of this line than ‘reacting with my head not my hands.’” An essay is supposed to tell the admissions committee something about yourself that is not revealed in the application, Maciag points out. “I did not get this from the essay. I felt the essay included too many details about the accident that had no bearing on the lesson learned.” Mulligan points out that the essay does achieve something critically important. “It was engaging from the start,” she says. “The subject matter caught my attention and kept me reading to find out how it all ended. In the days when admissions folks are reading

maintains that the subject matter was potentially risky, as some colleges might view the author as “a rather spoiled, a suburban poet without any real wisdom to impart.” “While good writing is good writing, period,” Lear explains, “students need to tell a good story and try to exhibit some real depth. Introspection is an underrated trait, and students are often quick to wrap up their essays too simply or neatly. Embracing ambiguity and thinking deeply before writing are two tips I would offer seniors.” “I thought it was well written, but it ultimately left me scratching my head,” says Cohen, who wanted to know more about the student than was revealed in the essay. “It didn’t tell me enough about the writer as a person. He/she spent entirely too much time on the accident. Ultimately schools are looking for Who are you? How are you going to fit in?” “I like the line about the ‘grave consequences await both my actions and inactions,’’ says Maciag. “This line can send a powerful message. I feel a more substantive essay could have come out of this line than ‘reacting with my head not my hands.’” An essay is supposed to tell the admissions committee something about yourself that is not revealed in the application, Maciag points out. “I did not get this from the essay. I felt the essay included too many details about the accident that had no bearing on the lesson learned.” Mulligan points out that the essay does achieve something critically important. “It was engaging from the start,” she says. “The subject matter caught my attention and kept me reading to find out how it all ended. In the days when admissions folks are reading  thousands of essays this is so important—to keep eyes from glazing over and hold the attention of the reader. For the most part, he or she is a solid writer with a terrific vocabulary and good writing style. The essay puts the student in an interesting story, which I like.” When asked if the essay would be better for one type of school over another, Mulligan pointed out that this actually should not be a consideration for the main essay. “Students are attempting to tell the schools who they are,” she explains. “This is their big chance—often the only forum. It is not like Cinderella and the glass slipper, I tell my students. You are not trying to fit yourself into a school, or gear an essay to a school. You are trying to see if a school fits you, and so the essay is about you…and you should not change it to fit different tiers of schools.” To the What type of school… question, Lear had a more succinct response: “One that doesn’t allow freshmen to drive cars.”

thousands of essays this is so important—to keep eyes from glazing over and hold the attention of the reader. For the most part, he or she is a solid writer with a terrific vocabulary and good writing style. The essay puts the student in an interesting story, which I like.” When asked if the essay would be better for one type of school over another, Mulligan pointed out that this actually should not be a consideration for the main essay. “Students are attempting to tell the schools who they are,” she explains. “This is their big chance—often the only forum. It is not like Cinderella and the glass slipper, I tell my students. You are not trying to fit yourself into a school, or gear an essay to a school. You are trying to see if a school fits you, and so the essay is about you…and you should not change it to fit different tiers of schools.” To the What type of school… question, Lear had a more succinct response: “One that doesn’t allow freshmen to drive cars.”

common is a bumpy back-to-school period where teachers, administrators, moms and dads can struggle to regain their bearings. Unfortunately, there’s no review period for parents. “Communication is always critical to a successful school opening,” says Nancy Leaderman,

common is a bumpy back-to-school period where teachers, administrators, moms and dads can struggle to regain their bearings. Unfortunately, there’s no review period for parents. “Communication is always critical to a successful school opening,” says Nancy Leaderman, work extra-hard to establish ground rules. “With parents who are ‘overly involved,’ we use our best judgment about whether the classroom teacher, school guidance counselor or administrator should communicate appropriate and helpful boundaries in order to highlight increased success for student development,” she says. Conard embraces a similar approach with the families at Pingry. “Sometimes, you need to be quite direct before the school year starts,” he says. “It all comes back to shared recognition of the partnership between parents and the school.” One of the problems that Leaderman has dealt with at Golda Och are moms and dads who insist on a specific teacher for a student. “Parents often need to be reassured that we have appropriately placed their children in the correct levels, with the appropriate teachers and friends,” she says. Campbell Rush has had similar experiences, noting that a good deal of thought goes into class placement. “I don’t mind if parents come to us with valid concerns,” she says, “but they have to realize that we work very hard to achieve classroom balance.” One of the classic summer slide no-no’s is bypassing the chain of command. That could mean ignoring security stops or the administrative office when entering a school. Or it might be going over a teacher’s head and seeking an audience with a principal or administrator for what is strictly a classroom issue. As any educator will tell you, this type of behavior ultimately impedes the educational process.

work extra-hard to establish ground rules. “With parents who are ‘overly involved,’ we use our best judgment about whether the classroom teacher, school guidance counselor or administrator should communicate appropriate and helpful boundaries in order to highlight increased success for student development,” she says. Conard embraces a similar approach with the families at Pingry. “Sometimes, you need to be quite direct before the school year starts,” he says. “It all comes back to shared recognition of the partnership between parents and the school.” One of the problems that Leaderman has dealt with at Golda Och are moms and dads who insist on a specific teacher for a student. “Parents often need to be reassured that we have appropriately placed their children in the correct levels, with the appropriate teachers and friends,” she says. Campbell Rush has had similar experiences, noting that a good deal of thought goes into class placement. “I don’t mind if parents come to us with valid concerns,” she says, “but they have to realize that we work very hard to achieve classroom balance.” One of the classic summer slide no-no’s is bypassing the chain of command. That could mean ignoring security stops or the administrative office when entering a school. Or it might be going over a teacher’s head and seeking an audience with a principal or administrator for what is strictly a classroom issue. As any educator will tell you, this type of behavior ultimately impedes the educational process.

our child into a name-brand college. In doing so, however, we are committing a heresy of emphasis; we have become so obsessed with the outcome that we have overlooked the whole point of the process. As a Certified Educational Planner with many years in the trenches of the “admissions game” (as one colleague playfully refers to it), I have accumulated an abundance of two things: anecdotes and raw data. The data speaks for itself; in the end, numbers are numbers. But the anecdotes—the “data” lived out through the hearts, hands, and hormones of respiring teenaged beings—is why I cannot imagine doing anything else with my life. It is this passion that is incendiary with my students; it is the invisible permission slip for each of them to permit themselves to dream of a life and future that is so meaningful, so gratifying, so spectacularly promising, that they cannot help but begin to vision what it might be. Which is why nothing makes me cringe like hearing a parent say, “WE want to apply to…” My philosophy is this: Focus on the student’s process of growth and self-discovery in the college application process, and the ideal college match will be the beautiful consequence. Your child’s “reach” school may not even be on your radar when you begin. Thus your first and most important effort should be to identify the best possible destination—not just for those four wonderful years, but for the rest of his or her life. I may be uttering heresy to those Type A’s among us (myself included) who cleave to the Machiavellian means-to-an-end mentality of Why do anything if it doesn’t get you to the next level in life? But the experts back me up. Steve Antonoff, of Antonoff and Associates in Denver, Colorado, says this about people in my profession: “The treasure the consultant has is not the list, the treasure lies in figuring out who a young person is and helping them discover what colleges will be the best fit for them.” What Antonoff is gesturing at is that a great consultant—or a great guidance counselor, or a wise mentor—will do whatever it takes to: 1) cut through the teen peer-pressure culture that oppressively enforces conformity, 2) focus on students for who they are, and 3) mirror back to them the unique gifts with which they have been blessed. In my own practice, I encourage each young person not to put his or her light under a basket, but to hold it aloft so as to illuminate the room, the school, the community and, I daresay, the globe. Only then does a true picture begin to emerge of the “best possible college.” Only then can a young person start building an application strategy to get into that school. In that spirit, consider the experiences and outcomes of the following four students…

our child into a name-brand college. In doing so, however, we are committing a heresy of emphasis; we have become so obsessed with the outcome that we have overlooked the whole point of the process. As a Certified Educational Planner with many years in the trenches of the “admissions game” (as one colleague playfully refers to it), I have accumulated an abundance of two things: anecdotes and raw data. The data speaks for itself; in the end, numbers are numbers. But the anecdotes—the “data” lived out through the hearts, hands, and hormones of respiring teenaged beings—is why I cannot imagine doing anything else with my life. It is this passion that is incendiary with my students; it is the invisible permission slip for each of them to permit themselves to dream of a life and future that is so meaningful, so gratifying, so spectacularly promising, that they cannot help but begin to vision what it might be. Which is why nothing makes me cringe like hearing a parent say, “WE want to apply to…” My philosophy is this: Focus on the student’s process of growth and self-discovery in the college application process, and the ideal college match will be the beautiful consequence. Your child’s “reach” school may not even be on your radar when you begin. Thus your first and most important effort should be to identify the best possible destination—not just for those four wonderful years, but for the rest of his or her life. I may be uttering heresy to those Type A’s among us (myself included) who cleave to the Machiavellian means-to-an-end mentality of Why do anything if it doesn’t get you to the next level in life? But the experts back me up. Steve Antonoff, of Antonoff and Associates in Denver, Colorado, says this about people in my profession: “The treasure the consultant has is not the list, the treasure lies in figuring out who a young person is and helping them discover what colleges will be the best fit for them.” What Antonoff is gesturing at is that a great consultant—or a great guidance counselor, or a wise mentor—will do whatever it takes to: 1) cut through the teen peer-pressure culture that oppressively enforces conformity, 2) focus on students for who they are, and 3) mirror back to them the unique gifts with which they have been blessed. In my own practice, I encourage each young person not to put his or her light under a basket, but to hold it aloft so as to illuminate the room, the school, the community and, I daresay, the globe. Only then does a true picture begin to emerge of the “best possible college.” Only then can a young person start building an application strategy to get into that school. In that spirit, consider the experiences and outcomes of the following four students…

devices and e-readers (by this time next year there may be close to 100 out there!) seemed tailor-made for the technological needs and aspirations of schools at every level. Teachers, students and educational researchers all nod in agreement that we have come to at an important place in the evolution of learning. Things seem to be changing at light speed. The same pulse-quickening technology that drives lunchroom chatter is finding its way into classrooms all over the state in the form of SMART Boards, iPads and other devices that connect kids to information in attention grabbing ways. It’s an exciting time to be a student. For teachers, it’s a time of transition. They must evolve with the technology. Fortunately, the traditional forms of delivering information, despite losing ground, are not leaving the scene.

devices and e-readers (by this time next year there may be close to 100 out there!) seemed tailor-made for the technological needs and aspirations of schools at every level. Teachers, students and educational researchers all nod in agreement that we have come to at an important place in the evolution of learning. Things seem to be changing at light speed. The same pulse-quickening technology that drives lunchroom chatter is finding its way into classrooms all over the state in the form of SMART Boards, iPads and other devices that connect kids to information in attention grabbing ways. It’s an exciting time to be a student. For teachers, it’s a time of transition. They must evolve with the technology. Fortunately, the traditional forms of delivering information, despite losing ground, are not leaving the scene. Educational Advancement at Far Hills Country Day School, predicts that, 10 years from now, no one will be questioning the role of technology in schools. Everyone will have it and everyone will use it. “No longer will we be asking, ‘Should we use technology in this lesson?’ Technology will be portable and accessible all the time, everywhere—and a given tool for all learning.” When Donna Toryak of Mount Saint Mary Academy looks into her crystal ball, she predicts that paper, pencils and textbooks will be passé, and will no longer be a staple of the traditional classroom. “Online and virtual classrooms may replace what we now see as students sitting in rows at desks, listening to a lecture or annotating the day’s lessons. Technology is a very thrilling theme for the future.” The future has arrived at a growing number of New Jersey schools, and in some cases it’s in the hands of four-year olds. The Rumson Country Day School built a Passport to Adventure afternoon enrichment program around 10 recently purchased iPads. “Our pre-school iPad program enables students to learn through interaction with technology,” explains Laura Small, a teacher and administrator at RCDS. “They practice and master letter recognition, handwriting and math concepts technologically as well as traditionally.

Educational Advancement at Far Hills Country Day School, predicts that, 10 years from now, no one will be questioning the role of technology in schools. Everyone will have it and everyone will use it. “No longer will we be asking, ‘Should we use technology in this lesson?’ Technology will be portable and accessible all the time, everywhere—and a given tool for all learning.” When Donna Toryak of Mount Saint Mary Academy looks into her crystal ball, she predicts that paper, pencils and textbooks will be passé, and will no longer be a staple of the traditional classroom. “Online and virtual classrooms may replace what we now see as students sitting in rows at desks, listening to a lecture or annotating the day’s lessons. Technology is a very thrilling theme for the future.” The future has arrived at a growing number of New Jersey schools, and in some cases it’s in the hands of four-year olds. The Rumson Country Day School built a Passport to Adventure afternoon enrichment program around 10 recently purchased iPads. “Our pre-school iPad program enables students to learn through interaction with technology,” explains Laura Small, a teacher and administrator at RCDS. “They practice and master letter recognition, handwriting and math concepts technologically as well as traditionally.