What lies beneath may surprise you.

When the world imagines New Jersey, it pictures the opening drive from The Sopranos, an hours-long Bruce Springsteen concert, prizefights in Atlantic City, Tilly’s grin and the Asbury Park Boardwalk, Jersey Shore the reality show and Jersey Shore the beloved summer destination. New Jerseyans know better—there is a lot more to the state than meets the eye. For instance, we are surrounded by water on three sides, not just one, and our lakes and rivers offer endless opportunities for recreation. Something New Jerseyans may not know is that, under the surface of these picturesque bodies of water, there is a world of forgotten history, hidden secrets, and tantalizing clues to the past.

The Ice Age is a great place to begin our deep dive. During this period in Earth’s history, the frigid climate trapped a lot of the planet’s water in massive ice sheets, which in turn led to significantly lower sea levels—as low as 400 feet or more. The Atlantic coast extended far beyond what we now think of as the Jersey Shore. The Hudson River, meanwhile, didn’t end at Staten Island; it continued to cut through the exposed land for hundreds of miles, creating canyon three-quarters of a mile deep. We know it as the Hudson Canyon, a favorite fishing spot that also happens to be the largest known underwater canyon in the world. Too bad no one was around to see it back then.

Off the Hook

Guy Fleming

Well, hang on a minute. Do we know with absolute certainly that this land was unpopulated? The Ice Age ended and ocean levels began rising rapidly around 11,500 years ago. There is compelling evidence that humans had reached the Atlantic coast by then, which might have been 100 or more additional miles to the east. Called Paleo Indians by anthropologists, they would have hunted various now-extinct animals, including megafauna species that include mastodons, wooly mammoth and giant ground sloths. Evidence of their actual settlements would have been wiped away by the rapid rise of the ocean. However, fossilized animal bones are occasionally recovered far off shore, confirming that what we think of as the “sea floor” was once teeming with animals in the not-too-distant past.

In the 1990s, an ambitious dredging operation took place at the northern end of the coast to replenish eroding beaches. Much of the sand scooped up from a mile or more offshore was deposited in front of the towns of Sea Bright and Monmouth Beach—where beachcombers soon discovered hundreds of human artifacts, including stone tools and projectile points that pre-date the Lenape Indians who had inhabited the area before the coming of European settlers. These items appear to have been produced by the aforementioned Paleo Indians, at an offshore site that is believed to date back at least 10,000 years. The Paleo Indians spread across North America after arriving from northeast Asia via Beringia, the Ice Age land mass now submerged below the Bering Sea. When you stand facing the ocean, holding one of these ancient artifacts in your hand, it is impossible not to wonder what else is out there under the waves.

On the Lake Front

Upper Case Editorial

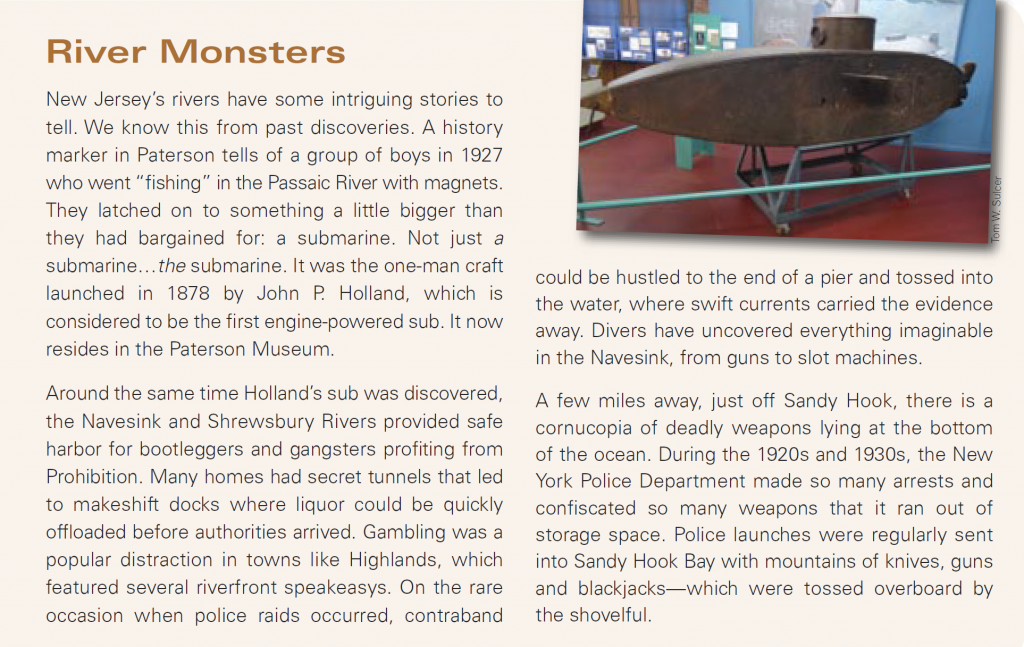

New Jersey’s lakes and ponds guard their share of secrets—some ancient and others from recent history. In 1954, Gus Ohberg, owner of a Sussex County sports shop, decided to expand the small lake on his property in Vernon Township. During the dredging, one of the workers spotted a large brown bone, which turned out to be a mastodon skull. Professionals were summoned to the site and eventually they uncovered the most complete mastodon skeletons ever found. The Ohberg Mastadon—renamed “Matilda” after the bride of one of the archaeologists on the project—was reassembled in Trenton, where it remains a favorite attraction at the State Museum more than six decades later. Matilda was a young female, a teenager, whose remains were carbon-dated to around 11,000 years old—near the end of the mastodon’s reign over North America, likely due to a combination of human hunting, disease and loss of habitat brought on by the end of the Ice Age, when the glaciers that carved through the northern half of New Jersey receded. Matilda may not have been the only member of her family to perish on the Ohberg property. Indeed, rumor has it that Mastodon Lake may have more secrets to reveal.

If you enjoy a mystery, know that the Round Valley Reservoir (right) in Clinton has been called “New Jersey’s Bermuda Triangle.” Since it opened to the public in the 1970s, more than 20 people have lost their lives swimming, boating and exploring there. People can’t resist a spooky story and, indeed, some insist the reservoir is cursed. Its allure to scuba divers, however, is the town that lies beneath its 55 billion gallons of water. The reservoir was completed in 1960, submerging a small farming community in the process. The project was initiated to meet Newark’s growing demand for water and Round Valley seemed like the perfect place to locate a reservoir.

All but one county (Hunterdon, where it was located) agreed, triggering eminent domain. Appraisers were sent to evaluate the 50 or so farms in the way so that the state could make an offer to residents that they literally couldn’t refuse. Some took the money and started anew. Others used a portion of the cash to re-purchase their family homes and then dismantle and physically relocate them. After it was all said and done—and tens of billions of gallons of water flooded the farms—the unthinkable happened: Newark pulled out. For the uninitiated, Newark’s relationship with its water supply has been historically (and often criminally) complicated, to say the least, and remains so. Thankfully, Round Valley still serves a purpose, as the water it sends through an underground pipeline makes its way to the Raritan River. And, as mentioned, it is a popular recreation and relaxation spot. Scuba divers can explore the foundations of many houses, a church, and a school—and maybe even spot a skeleton or two. It’s like New Jersey’s own little Atlantis.

Near the Shore

Deathworm

For more than three centuries beginning in the 1600s, the New Jersey coast was known unofficially as the graveyard of ships. Today, it has more shipwrecks per mile than any other state. Prior to the dredging of the current shipping channel in the 20th century, the approach to New York harbor was not a straight shot. Ships coming north had to hug the shoreline to remain in deep water, passing uncomfortably close to Sandy Hook in order to reach the Verrazano narrows. Vessels coming across the Atlantic had to aim directly at the shore and then make a hard turn to the right to find a channel deep enough to safely make it to port. An inexperienced captain or a violent storm could run a ship onto the sandbars, where it would be smashed to pieces.

One of the oldest wrecks off the coast of New Jersey is the HMS Zebra, a 14-gun sloop built by the British in 1777 to help crush the American Revolution. Its voyage ended abruptly in the fall of 1778 when the ship ran aground near Little Egg Harbor. The Zebra was part of the naval force controlling traffic in and out of the Delaware River, ensuring a constant flow of men and material to Philadelphia, one of the key cities in the colonies.

The struggle to control the waters around Cape May had been raging for two years by then. In the summer of 1776, the American colonists earned a critical early naval victory at the Battle of Turtle Gut Inlet, off Wildwood Crest. A spectacular American casualty in this meeting was the Nancy, a newly constructed brig that had sailed up from the Caribbean with a crew of 11, loaded with rum, sugar, gunpowder and arms. The British had already established a naval blockade of the area, with more than 200 cannons protecting the Delaware River. The Nancy (above) was spotted and pursued by a pair of British warships up the Jersey coast to the inlet, where it was purposely run aground so that longboats could be rowed out to salvage her precious cargo.

Winterthur Collection

The larger British vessels had to remain in deeper waters, but were close enough to fire on the salvage mission. The Nancy’s cannons fired back. When the offloading was complete, the Nancy’s flag was lowered, which the enemy took for a sign of surrender. Moments after boarding the disabled vessel, British forces discovered it was a trap: Using the Nancy’s mast as a fuse, the Americans had left 100 kegs of gunpowder aboard to blow her to splinters, sending more than a half-dozen redcoats to oblivion. The official seal of Wildwood Crest commemorates this event and the town also has a park with a memorial to those who served on the Nancy.

The wreck of the Nancy was a key moment in the early history of what was to become the U.S. Navy. Another maritime incident off the Jersey Shore gave birth to the U.S. Lifesaving Service, antecedent to the Coast Guard. A February 14th nor’easter in 1846 claimed several ships—some five off Sandy Hook alone—but it came to be known as the Minturn Storm. Among the casualties of the howling winds and driving snow was the Alabama, which ran aground near the Manasquan Inlet. A rescue attempt by ill-equipped locals failed and the crew perished. Many of the same good Samaritans turned their attention to the John Minturn, just four miles away in Mantoloking, later that day. The three-masted packet ship was carrying passengers and cargo from New Orleans when it slammed into the sand about 300 yards from shore. The rescuers worked for 18 hours and had more luck than with the Alabama, but there was still a tremendous loss of life. Only 10 people out of 50 survived and frozen bodies littered the beach.

No good deed goes unpunished and, sure enough, news stories reported that many of the bodies had their pockets turned inside out, calling the locals “barbarians.” The sensational tales triggered an investigation, which found that these people had risked their lives to save others, not to relieve corpses of their valuables. One account claimed that a body of a man wearing a gold belt buckle had washed up in Point Pleasant and was returned to his family still wearing the belt. The publicity generated by the Minturn Storm gave U.S. representative William Newell the momentum needed to push for the formation of an organized lifesaving corps. Two years later, the Newell Act called for the construction of a series of buildings to house the proper equipment to save people from wrecked ships. These Life Saving stations, which eventually popped up all over the east coast, were originally built along the shore from Sandy Hook to Little Egg Harbor, giving brave volunteers real equipment and a real chance of saving people.

Dan Lieb, president of the New Jersey Historical Divers Association, lists the John Minturn among the “Holy Grail” shipwrecks that he hopes to explore one day. Right up there with it is the New Era, which slammed into an outer sandbar off Asbury Park in 1854. Hundreds of passengers—mostly German immigrants—clung to the ship’s rigging, hoping to ride out the storm. Some made it, but most didn’t. About half of the 300-odd victims were interred in a West Long Branch cemetery, where a monument marks their mass burial. All kinds of rumors and controversy surrounded the wreck, most of which still linger to this day. Neither the John Minturn nor the New Era has been found yet—or, at least, not that Lieb knows. Often divers who discover a new wreck keep it to themselves.

By rough count, there are more than 5,000 sunken ships within 20 miles of the New Jersey coastline— hundreds of which can be explored by experienced divers. They include boats torpedoed during the two World Wars and victims of maritime collisions, an inevitable result of a busy shipping lane and unpredictable weather.

Upper Case Editorial

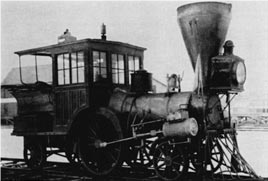

According to Lieb—who has completed over 2,000 dives since being certified in 1974—perhaps the most intriguing underwater wreck in New Jersey is not a shipwreck, but a trainwreck. A few miles off the coast of Long Branch, under 90 feet of water, two 1850s-era locomotives sit, nestled in the soft sand, side-by-side about 10 feet apart. Discovered in 1985, the trains are small (even for their time), weighing 15 tons apiece. The wheel layout is curious: three on each side, with the middle wheel larger than its neighbors. Their pattern of design (above) was common in England, Lieb points out, but a bell retrieved from the site raises the possibility that they may have been manufactured in Boston—or more likely the bell was added in Boston as the trains passed through New England on their way to their still-unknown final destination. It is not clear when the trains were lost, either. There are a number of scenarios that would pin their demise to a specific date, which could range from the 1850s to the end of the 19th century. For instance, the locomotives could have been headed to buyers in the Caribbean or South America, where rail systems were just being established, many decades after they were manufactured.

“Were they on their way to another country because they had become obsolete in America?” Lieb wonders. “I have visited them several dozen times. It’s quite interesting to see land-based vehicles underwater. They look so out of place.”

Another unknown is how the locomotives reached their final resting place. Obviously, they were being transported on a barge or some other vessel. But where is it? In 30-plus years of underwater exploring, no wreckage has been found. And what were the circumstances of their trip to the bottom? Did they break loose in heavy seas? Were they intentionally cut free, either to save the ship or perhaps to generate an insurance claim? Was it sabotage? None of these scenarios can account for the odd position in which they were found.

New Jersey’s waters have many more stories to tell. They provide snapshots of the past, protecting history from the elements of the surface world and preserving countless undiscovered treasures for future generations to explore.

Editor’s Note: The goal of the New Jersey Historical Divers Association (njhda.org) is to identify shipwrecks and bring their history to life. For those interested in exploring underwater New Jersey, a great starting point for new divers is to join a club or associate themselves with a dive shop and ask for recommendations.