’Tis the season. No, not of family gatherings and holiday cheer. For college-bound seniors and their parents, it’s crunch time.

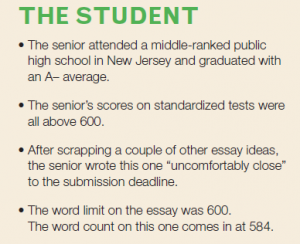

College admissions officers are bracing themselves for the tsunami. Over the next few weeks, the steady stream of applications they have been wading through will turn into an unstoppable torrent. One of the countless charms of the Internet is that it has made the process of applying to multiple schools incredibly simple. A generation ago, high-school seniors would pick a handful of schools—including a reach and a safety—fill out the paperwork by hand, lick the envelope, stamp it, and send it off. Thanks to the common application (aka The Common App) and the wonders of technology, today every one of the 3.5 million teenagers thinking about college can apply to 20 schools with only slightly more effort than it took to lick those envelopes. One thing about teenagers hasn’t changed. No matter how easy the computer has made it for them to apply to college, they somehow find a way to turn the process into a full-on heart attack anyway. The majority of kids will be pushing the SEND button on their applications just a day or two before the deadline. Some will take it down to the final minutes or seconds. While frustrating for parents, engaging in this type of brinksmanship isn’t what should concern the moms and dads of college-bound seniors. The critical time-management issue is making sure that enough thought and effort have been devoted to the creation of an essay for the common application that grabs the attention of even the most overwrought admissions officer. It is the piece that tells a college who a young person is, and helps determine whether he or she would be a good fit for the school. Is your senior‘s essay done? I’m guessing the answer is no. Remove your fingers from around your child’s neck for a moment and take a look at what another kid did. I asked four professionals in the college admissions process to critique this essay. I made it clear that the writer had already matriculated, so we weren’t fishing for praise. Instead, we were looking for specific, constructive criticism that would help members of the Class of 2013 evaluate their college essays as the application deadline nears….

THE ESSAY When life hits you in the face, react with your head, not your hands. I never really knew what my parents were talking about until that awful Sunday afternoon in May. I had struck a section of guardrail with such force, and at such an unusual angle, that it lifted two of the supporting stanchions completely out of the ground. Luckily, I was unhurt. The culprit was long gone. Not a drunk driver. Not some idiot wolfing down a Quarter Pounder while texting on his cell phone. Rather, it was an enormous beetle that had flown through the open, driver-side window—smack into my face. A novice behind the wheel, I swerved left, over-corrected right, and finally lost control at 50 miles per hour. Precisely six weeks after posing for my first driver’s license photo, I had become a cliché. I was shocked and angry and embarrassed. The car was a twisted wreck. It had collapsed around me, absorbing the energy of my high-speed, metal-on-metal encounter. Totaled. It was only later, when I saw photos of the car and revisited the scene of the accident, that I realized how fortunate I was. Had I swerved 20 feet sooner I might have been cleaved by a telephone pole. Had I left the road 20 feet farther down the hill, I would have launched myself into a ravine. Teenagers are not wired to contemplate their own demise, yet whenever I drive past this spot it is hard to think of anything else. In time I realized something slightly more profound. By handing the keys to a newly minted driver, mom and dad were giving me that first terrifying (for them) taste of true independence that’s part of the letting-go process of parenthood. While all I saw was the upside, they had quietly thought through the downside and purchased the automotive equivalent of a Panzer—a used Audi wagon that was basically conceived and constructed to crash into guard rails and deliver young drivers back to their parents older, wiser and relatively unscathed. I might mention here that I had lobbied briefly for a Thunderbird convertible (yeah, dream on!). It’s less than a year later and my parents are now preparing to hand me the keys to a college education. They will be writing out another large, painful check and making me the driver of my own life. How terrifying this is for them I can only guess. Recently, I found myself telling a friend “when life hits you in the face, react with your head, not your hands.” She wasn’t really sure what I was talking about, but a few weeks later, she found herself wrapped around a telephone pole thanks to an adventurous squirrel. At this point, it is safe to say that almost everyone in our group of friends has both heard and understood this bit of wisdom. Of course, part of giving advice is accepting that advice yourself. And in that spirit, I would like to tell my parents what I have learned. Next time I will react with my head and not my hands. That’s a no-brainer, so to speak. And although I still feel indestructible, I also know grave consequences await both my actions and in-actions. Mostly what I’d like to tell them is that in choosing a college, I now know I’m looking for the Audi, not the T-bird. I’d like to tell them…but I won’t. As they taught me, sometimes you just have to figure things out for yourself.

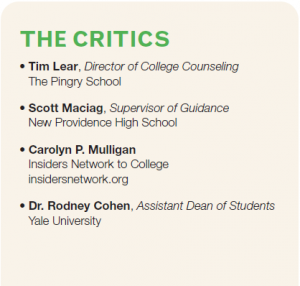

THE FEEDBACK All four of our experts agreed on two things. The essay demonstrated excellent writing skills, but also fell short of that certain something admissions officers love to see in an essay: Wow Factor. “I really enjoyed the opening. It grabbed my attention and piqued my curiosity,” says Lear. However, he  maintains that the subject matter was potentially risky, as some colleges might view the author as “a rather spoiled, a suburban poet without any real wisdom to impart.” “While good writing is good writing, period,” Lear explains, “students need to tell a good story and try to exhibit some real depth. Introspection is an underrated trait, and students are often quick to wrap up their essays too simply or neatly. Embracing ambiguity and thinking deeply before writing are two tips I would offer seniors.” “I thought it was well written, but it ultimately left me scratching my head,” says Cohen, who wanted to know more about the student than was revealed in the essay. “It didn’t tell me enough about the writer as a person. He/she spent entirely too much time on the accident. Ultimately schools are looking for Who are you? How are you going to fit in?” “I like the line about the ‘grave consequences await both my actions and inactions,’’ says Maciag. “This line can send a powerful message. I feel a more substantive essay could have come out of this line than ‘reacting with my head not my hands.’” An essay is supposed to tell the admissions committee something about yourself that is not revealed in the application, Maciag points out. “I did not get this from the essay. I felt the essay included too many details about the accident that had no bearing on the lesson learned.” Mulligan points out that the essay does achieve something critically important. “It was engaging from the start,” she says. “The subject matter caught my attention and kept me reading to find out how it all ended. In the days when admissions folks are reading

maintains that the subject matter was potentially risky, as some colleges might view the author as “a rather spoiled, a suburban poet without any real wisdom to impart.” “While good writing is good writing, period,” Lear explains, “students need to tell a good story and try to exhibit some real depth. Introspection is an underrated trait, and students are often quick to wrap up their essays too simply or neatly. Embracing ambiguity and thinking deeply before writing are two tips I would offer seniors.” “I thought it was well written, but it ultimately left me scratching my head,” says Cohen, who wanted to know more about the student than was revealed in the essay. “It didn’t tell me enough about the writer as a person. He/she spent entirely too much time on the accident. Ultimately schools are looking for Who are you? How are you going to fit in?” “I like the line about the ‘grave consequences await both my actions and inactions,’’ says Maciag. “This line can send a powerful message. I feel a more substantive essay could have come out of this line than ‘reacting with my head not my hands.’” An essay is supposed to tell the admissions committee something about yourself that is not revealed in the application, Maciag points out. “I did not get this from the essay. I felt the essay included too many details about the accident that had no bearing on the lesson learned.” Mulligan points out that the essay does achieve something critically important. “It was engaging from the start,” she says. “The subject matter caught my attention and kept me reading to find out how it all ended. In the days when admissions folks are reading  thousands of essays this is so important—to keep eyes from glazing over and hold the attention of the reader. For the most part, he or she is a solid writer with a terrific vocabulary and good writing style. The essay puts the student in an interesting story, which I like.” When asked if the essay would be better for one type of school over another, Mulligan pointed out that this actually should not be a consideration for the main essay. “Students are attempting to tell the schools who they are,” she explains. “This is their big chance—often the only forum. It is not like Cinderella and the glass slipper, I tell my students. You are not trying to fit yourself into a school, or gear an essay to a school. You are trying to see if a school fits you, and so the essay is about you…and you should not change it to fit different tiers of schools.” To the What type of school… question, Lear had a more succinct response: “One that doesn’t allow freshmen to drive cars.”

thousands of essays this is so important—to keep eyes from glazing over and hold the attention of the reader. For the most part, he or she is a solid writer with a terrific vocabulary and good writing style. The essay puts the student in an interesting story, which I like.” When asked if the essay would be better for one type of school over another, Mulligan pointed out that this actually should not be a consideration for the main essay. “Students are attempting to tell the schools who they are,” she explains. “This is their big chance—often the only forum. It is not like Cinderella and the glass slipper, I tell my students. You are not trying to fit yourself into a school, or gear an essay to a school. You are trying to see if a school fits you, and so the essay is about you…and you should not change it to fit different tiers of schools.” To the What type of school… question, Lear had a more succinct response: “One that doesn’t allow freshmen to drive cars.”

Editor’s Note: Assignments Editor Zack Burgess writes on culture, politics and sports for a number of publications and web sites. His work can be seen on zackburgess.com. The young author of the essay in this story was accepted by (and now attends) a Top 30 university.