Abraham Browning Photo courtesy of NJ.gov

Why do our license plates say Garden State? Unless you are in law enforcement, it is doubtful that you spend a lot of time thinking about license plates. However, if you are 60 or younger, that slogan has probably been attached to every car you or your family has ever owned. At the time Garden State was added to our license plates in 1955, the term had been in use as an unofficial nickname for well over half a century. The characterization of New Jersey as a garden may not seem right to out-of-towners, but anyone who has spent any time here knows how incredibly productive the soil is in all but a couple of places. In the 1700s and 1800s, New Jersey served as the primary food source for two of the nation’s fastest-growing cities, New York and Philadelphia. Benjamin Franklin likened our state to a barrel of food, open at both ends, nourishing two major populations.

Legend has it that the term Garden State came into wide use after the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. During that event, Abraham Browning, New Jersey’s Attorney General in the years prior to the Civil War, gave a speech in which he described his home state as “an immense barrel filled with good things to eat and open at both ends—with Pennsylvanians grabbing from one end and the New Yorkers from the other.” It was during this speech that he supposedly dubbed New Jersey the Garden State. When the license plate bill was introduced in Trenton in 1954, Governor Robert Meyner decided to investigate the origin of the slogan and determined that at no time had it ever been recognized officially. Focused on promoting the state’s growing reputation as a business-friendly industrial player, Governor Meyner felt the word garden sounded too rural—and actually vetoed the bill! “I do not believe that the average citizen of New Jersey regards his state as more peculiarly identifiable with gardening for farming than any of its other industries or occupations,” he said. The legislature ignored him, overrode the veto, and early the next year the new license plates started arriving at Motor Vehicles.

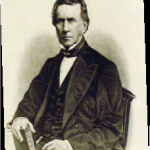

Photo courtesy of Fabioj

Who came up with the Big Bang theory? If you were hoping to read about Leonard, Sheldon, Howard and Raj, skip to the next teachable moment. This Big Bang happened billions of years ago—and was “discovered” by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson in 1965. The two radioastronomers, working at Bell Labs in Holmdel, were interested in measuring radio signals coming from space. They were given permission to use a satellite receiver (from an obsolete project called Echo), which was destined for the scrapheap. It just happened to be perfect for their experiments. As soon as Penzias and Wilson began, they noticed a static-y background signal in the microwave range.

Until they eliminated this mysterious noise, they could not continue with their work. The problem was complicated by the fact that, no matter where they pointed the receiver, they heard the same noise. They began ruling out various possibilities. It was not an extra-terrestrial radio signal. It had nothing to do with nearby New York City. An above-ground nuclear test was not the culprit either. It occurred to the scientists that perhaps the pigeons living in the antenna were creating the problem. They shooed them away and then swept out their poop themselves. Next, they turned to the work of others. In 1929, Edwin Hubble had shown that the galaxies we could see from earth seemed to be moving away from us. This suggested that the universe had been compacted at some point.

In England, astrophysicist Stephen Hawking and two colleagues were taking Albert Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity and trying to work backwards to measure time and space. The conclusion they drew was that time and space had a “beginning”—and that all matter and energy originated at that point. Closer by, in Princeton, Robert Dicke theorized that if such an origination point existed, then the residue of the “big bang” that created the universe would be evident in consistent, low-level background radiation anywhere you looked. What Dicke needed was evidence. After four frustrating seasons, Penzias and Wilson began reaching out to their colleagues. They contacted Dicke and presented their dilemma. Of course, he knew exactly what the noise was. Dicke shared his theoretical work, knowing he’d been “scooped.” The three scientists published their findings and in 1978, Penzias and Wilson received the Nobel Prize. One wonders if they could have imagined this outcome more than a decade earlier, while they were sweeping bird droppings off their receiver.

How did our bridges and tunnels get built? New Jerseyans don’t like it a bit when Manhattanites deride them as the “Bridge & Tunnel” crowd. But bridges and tunnels provide vital lifelines for urban dwellers and, lest we forget, they do not build themselves. In the case of the Holland Tunnel to New York and the Ben Franklin Bridge to Philadelphia, credit goes to the vision, political will and—surprise!—unbridled corruption of two of the state’s iconic influence-peddlers: Frank Hague and Enoch “Nucky” Johnson. Hague clawed his way to power in Hudson County beginning in the 1890s, rising from the job of Jersey City constable to ward boss to City Commissioner by 1913. During World War I, Hague filled a power vacuum and seized control of the state’s most populous and richest county.

He was elected Jersey City Mayor in 1917. Johnson, the inspiration for Nucky Thompson in the HBO series Boardwalk Empire, held a number of different official positions in Atlantic City. He ascended to role of political boss in 1911 after his predecessor was jailed. He quickly consolidated this position and held it for three decades. To stimulate business for his town, Johnson made sure that city officials looked the other way when it came to enforcing laws against gambling, prostitution and liquor. When Prohibition kicked in a few years later, Atlantic City became a Mecca of vice and Johnson’s take on this illicit business was hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. Between the two machine bosses, they controlled enough money and manpower in New Jersey to get almost anything done— or make almost anyone disappear. They first joined forces in 1916. Johnson was the campaign manager for Walter Evans Edge, a state senator from Atlantic County who had his eye on the White House.

The first step was to get him to the governor’s mansion. This would be tricky, as Edge was a Republican and Hague was a Democrat who controlled votes in the northern half of the state. Johnson (then 33) met with Hague (then 40) and suggested they forge a partnership that would serve both their ambitions going forward. Hague instructed his organizers to make sure Edge won the Republican primary, and then yanked his support from a stunned Democratic candidate Otto Wittpenn in the general election. With Edge running things in Trenton, Johnson’s power grew. The new governor rewarded him by making him Clerk of the State Supreme Court. He also pushed through laws that gave New Jersey’s cities more autonomy, which helped solidify Johnson and Hague as machine bosses. In 1917, Governor Edge “rewarded” Johnson and Hague by reorganizing the state highway department. This enabled him to authorize the construction of a bridge between South Jersey and Philadelphia (the Ben Franklin Bridge) and a tunnel between Jersey City and Manhattan (the Holland Tunnel).

The bridge opened in 1926 and the tunnel opened in 1927. Both projects transformed the cities that Johnson and Hague controlled. After 30 years, the law finally caught up with Johnson. For years, he had listed enormous amounts of income from gambling, prostitution and kickbacks on his tax return as “other contributions.” The IRS finally nailed him in 1941. Hague fared better during FDR’s administration. Indeed, the lion’s share of federal funds earmarked for New Jersey was put under Hague’s control, conspicuously bypassing the state’s senators or governors. Hague finally resigned as Jersey City Mayor when the new state constitution went in place in 1947.

It was rewritten largely to curtail the influence of local political bosses, and he knew it. Edge went on to enjoy a long and productive national and state political career, but never made it to the White House. He was the fron-trunner for vice president on Warren Harding’s ticket in 1920, but enemies he made with his wheeling and dealing in the Garden State blocked his candidacy, and Calvin Coolidge ended up as Harding’s running mate. Coolidge ascended to the presidency after Harding died in office. Who knows what New Jersey would look like today had Edge been president instead of Coolidge. One can only imagine the extent to which Frank and Nucky might have elevated their power.

Photo Courtesy of Twin Lights Historical Society

Where was the Pledge of Allegiance given for the first time? The Pledge of Allegiance was first published on September 8, 1892, in The Youth’s Companion, a children’s magazine that enjoyed wide circulation across the United States. On April 25, 1893, the Pledge was given for the first time as America’s official national oath of loyalty in a ceremony atop the Navesink Highlands, overlooking Sandy Hook. How the Pledge made this extraordinary journey in less than eight months is a story that is still not covered in most textbooks. The Pledge originated in the offices of The Youth’s Companion in Boston as part of a promotion to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus discovering America.

The publisher’s nephew, James Upham, was in charge of marketing the publication. His goal was to sell flags through advertising that appeared on the magazine’s back pages. Knowing that schools did not typically have flags in their classrooms, he came up with the clever idea of having students recite a pledge of loyalty to the flag at the start of each school day. At a time when patriotism in America was on the rise, this seemed like a sure bet. The writer of the pledge was Francis Bellamy, a local Baptist minister and occasional contributor to the Companion. He may or may not have had editing help, but the final result was I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. An ardent socialist, Bellamy had originally include the words equality and fraternity in the Pledge. It was decided that no one quite knew what fraternity meant (it was an expression held over from the French Revolution), and that equality might offend those who frowned upon the notion than women and African Americans might share in the advantages enjoyed by white males.

The Pledge of Allegiance immediately caught the attention of President Benjamin Harrison, who was running for reelection that fall. Harrison proclaimed that October 12 would now be Columbus Day, and ordered that the Pledge be recited in schools on that morning. It soon became a daily practice in many schools, and at various public events. Harrison ended up losing the election to Grover Cleveland (the nation’s only NJ-born president), but Cleveland continued to carry the ball on the Pledge. As the April 1893 opening of the Colombian Exposition in Chicago approached (it was a year late because of construction delays), it became clear to Cleveland and others in his administration that a “mirror event” somewhere on the East Coast would be necessary. A Newark businessman named William McDowell entered the picture at this time. On his various return trips from Europe via steamship, McDowell noted that the greatest commotion on board was not when the incoming immigrants passed that new statue, Liberty Enlightening the World, but upon the first sighting of the coastline. The first piece of America immigrants saw rising over the horizon on their way into New York Harbor was the Navesink Light Station, better know as the Twin Lights. McDowell believed there should be a flag atop the highlands, between the two lights, that was double their height.

Having already secured funds to erect this 135- foot Liberty Pole, he joined forces with The Youth’s Companion and government officials to hold a ceremony to make the Pledge of Allegiance “official” at the same time the Chicago World’s Fair was opening. On April 25th, several hundred local and national dignitaries gathered on a hastily constructed grandstand to witness the dedication of the Liberty Pole at the Twin Lights. It was a miserable, drizzly morning punctuated by several speeches and flag raisings. The Pledge of Allegiance was given for the first time as the official oath of loyalty. A flotilla of international warships fired salutes as it made its way north toward Sandy Hook. The following day, the ships were assembled for a naval review in New York Harbor, followed by parades and a couple of days of social events. Because Cleveland chose to bypass the flag-raising (he managed to make the parties in New York) and because almost every reporter of note in America was in Chicago to cover the Colombian Exposition, the day the Pledge became official never made it into the history books. The wording has changed a couple of times in the last 120 years, and the way we salute the flag has, too. One thing, however, remains the same—the Pledge of Allegiance is the symbolic final threshold every new American must cross before he or she becomes a U.S. citizen.