Do adoptees have an edge in the celebrity department?

By Mark Stewart

On January 1, 2017, a new law went into effect that has proved to be a game-changer for thousands of New Jerseyans. Anyone adopted in the state can have their records unsealed and view their original birth certificates. For the vast majority of children born prior to the 1990s—when the idea of “open adoptions” began to gain momentum—the answer to the question Who am I? has been Who knows? Since the new law went into effect, several thousand adoptees have petitioned to receive their un-redacted birth records. Birth parents can request their identifying information be redacted, but thus far, only a few hundred have done so.

In many cases, the biological parents are as curious to see how their progeny turned out as their children are to learn more about their family origins. This really isn’t much of a surprise. Imagine having put a child up for adoption and wondering for years, or even decades, how that child made his or her way in the world. The hope for any biological parent is that the baby grew up happy, healthy and found success as an adult.

Okay, now take it a step further—think about what it might be like to discover that your biological offspring became a star. There are no hard statistics on how often this comes to pass. But you’d be surprised how many universally known and admired public figures were raised by adoptive parents.

Adoption comes in many shapes and sizes, of course. A considerable number of famous Americans, for instance, were adopted as children or teenagers by step-parents—including Bill Clinton and Truman Capote—while others were adopted by members of their own extended family. Clinton was originally William Jefferson Blythe III, while Capote was born Truman Parsons. Olympic gymnast Simone Biles was adopted by her grandparents after it became clear her mother, Shanon, could not kick her drug and alcohol problems. Eric Clapton, the child of an unwed teen mom, grew up believing that his grandmother was his mother and his mother was his older sister—although it does not appear he was ever formally adopted. Eric Dickerson, a Hall of Fame football star, was born under similar circumstances and adopted by his great aunt. He, too, grew up believing his mother was his older sister. Jesse Jackson was fathered by a neighbor, Noah Robinson, but adopted by Charles Jackson, the man his mother married the following year. He grew up having father-son relationships with both men.

In all of the aforementioned examples most, if not all, of the puzzle pieces required to complete the adoption picture were on the table. But what of the adoptees whose biological parents willingly relinquished their rights at (or shortly after) birth? The list of celebrities who were given up as infants is equally impressive. The world of commerce and industry, for example, is peppered with examples of adoptees who became successful business leaders. In some cases, they took over family businesses and helped them expand and flourish. Steve Jobs and Dave Thomas are perhaps the two most famous businessmen who were given up for adoption as infants.

Matt Buchanan

Jobs, the visionary industrial designer who co-founded Apple, was put up for adoption in San Francisco in 1955. His biological parents—the son of a wealthy Syrian family and the daughter of a Midwestern farm family—met as students at the University of Wisconsin. Jobs was conceived during a summer visit to Syria. Religious differences (he was Muslim, she Catholic) made marriage problematic. Initially, Jobs’s birth mother hoped to place him with a wealthy couple. However, at the last minute that couple decided they wanted a girl. Her baby boy was placed instead with Clara and Paul Jobs, a Bay Area working- class couple. She refused to sign the adoption papers until the Jobses agreed that he would go to college. Two years later, the family adopted a girl, Patricia. She and Steve grew up in Los Altos, a town with great schools and a high density of engineering families. Jobs tracked down his biological parents in his 30s, with the help of a letter from the doctor who had arranged the adoption, which was delivered after his death. Jobs ended up forging a relationship with his biological mother after his own mother passed away.

The Wendy’s Company

Thomas, the man behind the Wendy’s fast-food empire, is a Jersey boy. He was born in Atlantic City in 1932 to a single mother and adopted at six weeks. Sadly, his adoptive mother died when he was five years old. He moved frequently with his father and lived with his grandmother for a time. Thomas landed his first restaurant job at the age of 12, in Nashville, Tennessee. At 15, he was working at a Ft. Wayne, Indiana restaurant when his father decided to move again. Thomas decided to stay put. He dropped out of school to work full-time. Thanks to his food-service background, Thomas was assigned to a base in Germany during the Korean War, where he was responsible for feeding 2,000-plus GIs a day. He returned to Indiana, where he began working with Harland Sanders, devising ways to make his Kentucky Fried Chicken franchises more profitable—and suggested Col. Sanders do his own commercials. Thomas founded Wendy’s in 1969 and ended up doing his own commercials, too—more than 800 in all. In 1992, Thomas started the Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption, which is dedicated to placing children in the foster care system into adoptive homes. Thomas passed away in 2002. His daughter, Wendy, serves on the foundation’s board.

Two of history’s most accomplished filmmakers—Michael Bay and Carl Dreyer—were given up as infants, albeit it was 75 years apart. Dreyer was born in Copenhagen to a successful farmer and a young girl who worked for his family as a maid. Dreyer’s father, who happened to be married, forced her to send the baby to an orphanage. The boy was adopted at the age of two by Carl Dreyer, a typesetter, and his wife, Inge. He left home at 16 to pursue his education and went into the film industry in his 20s. Dreyer moved to France, which was the epicenter of artistic filmmaking in the 1920s. In 1928, he made The Passion of Joan of Arc, a silent masterpiece that blended aspects of expressionism and realism, and broke ground in a number of artistic and technical areas. Four years later, Dreyer made the surrealistic classic Vampyr. The Joan of Arc picture has been hailed as the greatest European film of the silent era. Dreyer continued to make movies until his death in 1968.

Bjoern Kommerell

Michael Bay, who began interning with George Lucas as a high school student, was born in 1965 in Los Angeles. He was adopted by a Jewish family. His father was an accountant and his mother was a child psychiatrist. A cousin, Susan, was married to Leonard Nimoy. As a boy, Bay was drawn to his mother’s 8 mm camera. At age 8, he attached firecrackers to a toy train and staged an explosive accident. The fire department was called to extinguish the flames. Fast-forward to the 1990s, when he delivered lots of bang for the buck in Bad Boys (his directorial debut, starring Will Smith and Martin Lawrence), The Rock (with Nicholas Cage and Sean Connery) and Armageddon, in which the earth is nearly obliterated. Between 2007 and 2017, Bay made five Transformers features.

Two heralded writers were adopted shortly after birth, author

Robert Wilson

James Michener and playwright Edward Albee. Michener, whose books often focused on multi-generational family sagas, was born in Bucks County, Pennsylvania in 1907. He never learned anything about his biological parents. He was adopted by a Quaker woman named Mabel Michener and grew up in Doylestown. He taught during the Depression and then took a job with MacMillan Publishing editing Social Studies textbooks. Called to active duty during World War II, Michener traveled the South Pacific on a string of choice assignments as a naval historian because, legend had it, the Navy brass mistakenly assumed that he was the son of an admiral with a similar-sounding name. He drew on these experiences to write his first book, Tales of the South Pacific, in 1947. It provided the inspiration for the Broadway smash South Pacific, which opened two years after the book was published. During Michener’s career, 14 other books became movies or television miniseries. In 1977, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Univ Houston

Albee was born in Virginia in 1928 and brought to New York two weeks later, where he was adopted by a Westchester couple. His father, Reed Albee, owned several theaters and his grandfather, Edward II, was a wealthy vaudeville magnate. His mother, Frances, was an active socialite. Albee and his mother had a complicated relationship, which he later drew upon for his 1991 Pulitzer-winning play, Three Tall Women. He never felt close to his father either. He felt his parents never really understood much about parenting. Albee had a New Jersey connection; he attended the Lawrenceville School as a teenager, but was expelled long before he graduated. After college, he moved to Greenwich Village and began to write plays. He broke through in 1962 with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Four years later, Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor starred in the film adaptation. Albee won a total of three Pulitzer prizes and was arguably the most important American playwright of his generation. He passed away in 2016.

Looking back at the grand achievements of these individuals, it is interesting to plot out what role adoption played in their intellectual and personal development. In the case of entertainers, it’s anyone’s guess. One thing is certain: a significant number of commercially successful actors and musicians are adoptees. Some of their stories are inspiring, while others serve as reminders that the circumstances of adoption are not always neat and clean. A case in point is comic actor Tommy Davidson, who first starred in the FOX series In Living Color. Born to a single mother in Mississippi in 1963, he was literally left for dead in the trash at 18 months. The woman who rescued him, and ultimately adopted him, was white, as was her husband. He grew up in the toney D.C. suburb of Silver Spring as the older brother to two siblings, Michael and Beryl. Funny, smart and energetic, Davidson was one of the hottest stand-ups in the business in the mid-1980s and is still making movies three decades later.

Luigi Novi Wikimedia Commons

Hip-Hop pioneer Darryl McDaniels—the DMC of Run-D.M.C.—was born in New York City in 1964, surrendered as an infant to a Catholic orphanage, and adopted by his foster care family, the McDaniels, who chose not to reveal to their son that they were not his birth parents. Despite reaching the apex of his profession, the emptiness McDaniels felt drove him to the brink of suicide. As he tells it, he was “saved” after listening to Sarah McLachlan’s song “Angel” on the radio. Four years later, he learned the truth about his origins (“the missing piece to my existence“) and embraced his adoption as the first step to fulfilling his destiny. McDaniels was inspired to cut a remake of Harry Chapin’s “Cats in the Cradle” and asked McLachlan to participate. She not only agreed, she provided the band and the recording studio. When they finished, she said, “Darryl…I gotta tell you something. I was adopted, too.” McLachlan was born in 1968 in Nova Scotia and, like McDaniels, was adopted by her foster family as an infant. They have since joined forces on a number of initiatives in support of adoptee rights.

Three other high-profile sirens claim similar backgrounds: Faith Hill, Deborah Harry and Kristin Chenoweth. It might be worth noting that, from a stylistic standpoint, you probably couldn’t pick a more diverse trio. Hill, who’s got a closet full of Grammys and Country Music Awards, was born in Mississippi the same year as McLachlan and adopted by the Perry family, who named her Audrey Faith. In 1996, she fell in love with touring partner Tim McGraw and they were married that same year. Interestingly, McGraw, who was raised by a single mom, discovered at age 11 that he was the son of Mets pitcher Tug McGraw. After denying the relationship for several years, their increasing resemblance made Tug finally acknowledge his paternity.

Chris Ptacek

Kristin Chenoweth, a darling of the Broadway stage, was born in 1968, too. She was adopted at five days old by an Oklahoma family and found her niche as an actress and singer by age 12. After earning a scholarship to the Philadelphia Academy of Vocal Arts in 1993, she agreed to help a friend move from New Jersey to New York. On a lark, she auditioned for Animal Crackers at the Papermill Playhouse and won a featured role. She gave up her scholarship and later moved to New York to pursue her musical theater career, landing her first role on Broadway in 1997.

Deborah Harry, the iconic frontwoman for the new wave group Blondie, is a full-fledged Jersey Girl. She was born in 1945 in Miami as Angela Tremble but given up for adoption at three months to Richard and Catherine Harry, who owned a gift shop in Hawthorne. Harry broke free of her suburban roots as soon as she could and worked as a go-go dancer and Playboy bunny before launching her musical career. She always knew she was adopted, but not until she was in her 40s did she try to track down her birth mother (who had no interest in forging a relationship with Harry).

Finally, we have the realm of sports. No one has pushed the adoption conversation to the forefront in recent years more than the oversized star of baseball’s Yankees, Aaron Judge. He was born in 1992 in Linden, California, a one-stoplight town where he was adopted the next day by two local schoolteachers, Patty and Wayne Judge. They watched in astonishment as he grew to his current dimensions: 6’7”, 280 lbs., setting school records in baseball, football, and basketball. After a “cup of coffee” with the Yankees in 2016, he began terrorizing enemy pitchers in 2017 and won the Rookie of the Year award in a landslide. For now, he isn’t saying much about his biological parents, who one would guess from his appearance were some version of “mixed race.” Given his superstar status, and that it was a small town adoption, it’s unlikely the details will remain secret for long—even if he wants them to be.

Finally, we have the realm of sports. No one has pushed the adoption conversation to the forefront in recent years more than the oversized star of baseball’s Yankees, Aaron Judge. He was born in 1992 in Linden, California, a one-stoplight town where he was adopted the next day by two local schoolteachers, Patty and Wayne Judge. They watched in astonishment as he grew to his current dimensions: 6’7”, 280 lbs., setting school records in baseball, football, and basketball. After a “cup of coffee” with the Yankees in 2016, he began terrorizing enemy pitchers in 2017 and won the Rookie of the Year award in a landslide. For now, he isn’t saying much about his biological parents, who one would guess from his appearance were some version of “mixed race.” Given his superstar status, and that it was a small town adoption, it’s unlikely the details will remain secret for long—even if he wants them to be.

If Judge continues to hit homers and makes it to the Hall of Fame, he will not be the first adoptee in Cooperstown. That honor belongs to Jim Palmer, a six-time All-Star who won 268 games for the Baltimore Orioles between 1965 and 1984. Palmer was born in New York City in 1945 and adopted as an infant by a garment industry executive, Moe Wiesen, and his wife Polly. The Wiesens lived in Westchester County until Jim was 10. His father died in 1955 and his mother moved Jim and his sister to California. There she met and married Max Palmer, an actor. Jim still went by Wiesen as he began to make a name for himself on the baseball diamond. At a Little League banquet where he was to receive three trophies, he asked the emcee to call him Jim Palmer. On Max Palmer’s 87th birthday, he told Jim that was the highlight of his life, and that he was proud to see his last name on each of the Cy Young Awards that Palmer won.

Two notable gold-medal Olympians were raised by adoptive parents, Dan O’Brien and Greg Louganis. O’Brien, the star of Nike’s “Dan and Dave” commercials in the early 1990s, won the decathlon in the 1996 Summer Games. His biological parents were Finnish and African-American. He was adopted by an Oregon couple and raised in Klamath Falls. Louganis, who won four gold (and one silver) diving medals between 1976 and 1988, was put up for adoption at eight months. His biological parents were Samoan and Swedish. He was raised in Southern California by Peter and Frances Louganis (Louganis is a Greek name) and had pushed his way into his older sister’s gymnastics and dance classes by the age of two. He began diving at the age of nine when his parents installed a backyard pool.

The world of pro football offers three intriguing adoption stories: Daunte Culpepper, Colin Kaepernick and Tim Green. Culpepper was voted an All-Pro NFL quarterback in 2000 and again in 2004, and his football roots run deep. His birth mother, Barbara Henderson, was the sister of Thomas “Hollywood” Henderson, a star linebacker for the Dallas Cowboys in the 1970s. She was serving time for armed robbery in a Florida prison when she gave birth to a baby boy. One day later, he was adopted by Emma Culpepper, who worked in the jail and raised a total of 15 children. At 17, her son stood 6’4” and was named Florida’s top high-school football player. He went on to play 12 seasons in the NFL, and continues to use his fame to support the African American Adoption Agency. Kaepernick, whose refusal to stand for the National Anthem in 2016 triggered a social media firestorm, was the mixed-race child of a destitute teen mother in Milwaukee. Shortly after his birth, he was placed with Rick and Teresa Kaepernick, a couple who had lost two sons to heart defects. The family moved to California, where Colin blossomed into a top-rated baseball pitcher and straight-A student. He turned down diamond scholarships to pursue his dream of playing college football, eventually landing a full ride at the University of Nevada. After being drafted in 2011 by the San Francisco 49ers, Kaepernick led the team to the Super Bowl in 2012.

Tim Green, a defensive star for the Atlanta Falcons from 1986 to 1994, became an author of both fiction and non-fiction books after his playing days. In 1997, he published A Man and His Mother: An Adopted Son’s Search. In the book, Green talks about how he believed his “rejection” at birth drove him to become a high achiever, but also to have poor relationships with women. After learning that a girlfriend’s mother had given up a child for adoption at about the same time he was born (1963), he launched a seven-year quest to locate his birth mother so he could let her know that she had made the right choice—that he was successful and happy.

Which is everything a biological parent could possibly hope for, isn’t it?

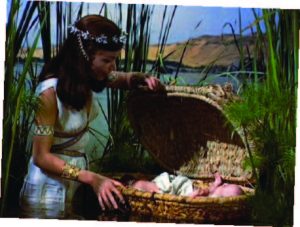

Paramount Pictures

THAT’S MY BOY!

The original “Star Child” adoptee came to us from the Old Testament, with an assist from Cecil B. DeMille. According to the story in Exodus, a Hebrew woman named Jochebed placed her newborn son in a waterproofed basket and floated him downriver after Pharaoh had ordered the male children of Israel killed. The infant was plucked from the bullrushes by an Egyptian princess and raised as Moses, a member of Pharaoh’s royal family. Although Moses achieved greatness as a member of Egypt’s ruling class, it was after he embraced his birth mother that he took it to the next level.

Given that Moses is one of the Bible’s most iconic figures, it stands to reason that it would take an actor with some gravitas to play (and also voice) him on-screen. Over the years, the part has gone to Christian Bale, Christian Slater, Peter Strauss, Val Kilmer, James Whitmore, and Burt Lancaster. The most amusing Moses was Mel Brooks in History of the World Part I. The most famous was Charlton Heston in The Ten Commandments.

Little known fact: Baby Moses (above) was played by Fraser Heston, Charlton’s son. Thirty-four years later, Fraser—who became a producer and director—cast his father as Long John Silver in the 1990 film Treasure Island.

MORE LIKELY? LESS LIKELY?

What are the odds that an adopted child will flourish and excel, compared to a child raised by biological parents? The answer depends on one’s definition of “success.” So much of what we achieve is linked to self-image. That can be complicated for adoptees. Baby Boomers, for example, grew up in an era where they had zero information on who had given them up, or why. On the one hand, these children grew up feeling good that they were “picked” by parents who desperately wanted them. On the other hand, there is a dark place every adoptee has gone when they wondered why they were “discarded.”

A survey done a decade ago generated some interesting statistics. Three out of four adopted children are read to (or sung to) every day. This is true for only half of biological children. Also, ninety percent of adoptees had positive feelings about the process—including an appreciation for the selfless act of their birth mothers.

WIN-WIN SCENARIO

WIN-WIN SCENARIO

Although some friends and family members may object to a young mother giving up a baby for adoption—or judge her harshly for the decision—statistics show that what is best for the baby usually has a positive outcome for the mother as well. Birth mothers are:

- No more likely to suffer from depression as single moms raising small children.

- Less likely to have a second out-of-wedlock pregnancy.

- More likely to delay marriage, but also more likely to eventually marry.

- Less likely to divorce.

- More likely to finish school.

- More likely to be employed 12 months after the baby is born.

- Less likely to live in poverty or receive public assistance.