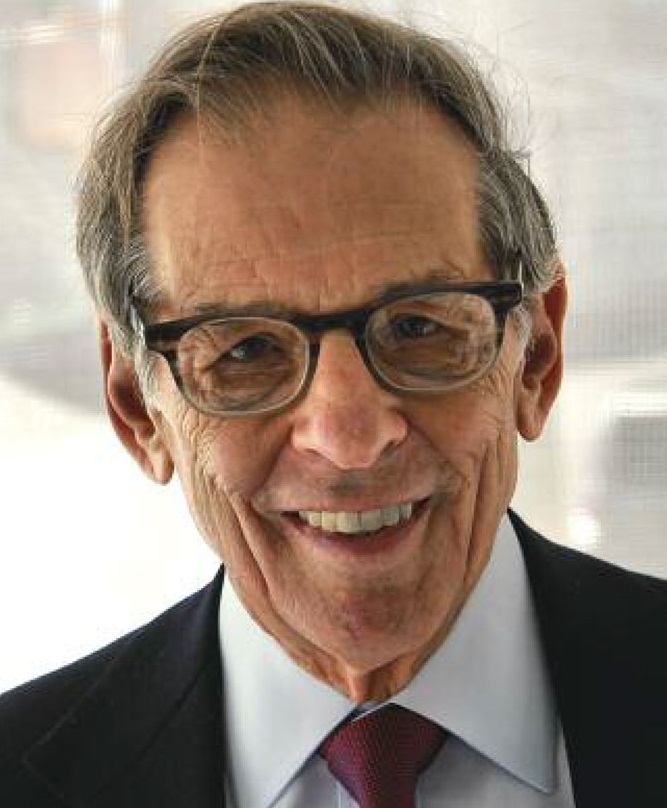

Robert A. Caro has spent nearly four decades chronicling the life of Lyndon B. Johnson, tracing his roots from a Texas farmhouse all the way to the White House. Through his biographies of Johnson and Robert Moses, Caro has illuminated the American political process and how power is wielded within our government. He is a recipient of the National Humanities Medal, and has won numerous other awards and accolades throughout his career. To EDGE interviewer Jesse Caro, he is something more than that: Caro is his grandfather (aka “Bop”). A recent college graduate embarking on a career in journalism, Jesse wielded his own political power to arrange a sit-down with the two-time Pulitzer Prize winning author. The topic: Caro’s own formative post-graduate experiences in his chosen profession.

EDGE: After graduating from Princeton—where you were the Managing Editor of the Daily Princetonian—you became a reporter. What drew you, early on, to journalism?

RC: That’s a question I’ve been asked before, but I’m not sure I know the answer to that. In the beginning, I liked trying to figure out how things worked, and wanted to explain that to people. When I first went to work for this little paper in New Jersey, I almost immediately narrowed that down to an interest in politics because, it seemed to me, that’s what matters. Almost immediately, I realized the idea of politics I had in college had very little to do with the way politics worked, and that I didn’t know how politics worked. Every day, I was learning something as a reporter. And since I felt like, if power in a democracy ultimately comes from us and the votes we cast, then the better informed people are about the realities of politics—not what we learned in textbooks in high school and college, but the way they really worked—the better informed our votes would be. And presumably the better our country would be. So I almost immediately started to be interested in politics for that reason.

EDGE: How did that lead you into investigative reporting?

RC: Purely by accident. I went to Newsday, and I was the low man on the totem pole. But Newsday was a crusading newspaper.

EDGE: Is that why you wanted to work there?

RC: Yes, that’s I wanted to work there. But I hadn’t done any crusading—I was still low on the paper. They had a managing editor named Alan Hathway, a figure straight out of the 1920’s and The Front Page—rambunctious, freewheeling, crusading. But he really didn’t like the idea of the Ivy League. He had always said he didn’t want anybody from the Ivy League in his city room. While he was on vacation, his assistant, I think as sort of a joke, hired me. Hathway was so mad when he came back, he wouldn’t talk to me. He would walk by my desk without saying a word. But Newsday was doing a terrific thing.

There had been an Air Force base in the middle of Nassau County called Mitchel Field, and the Air Force didn’t need it any more. Real estate developers were coming into to Nassau County and they wanted it.

EDGE: How was Newsday covering the story?

RC: Well, the FAA wanted to give most of the land to real estate developers and keep part of it as a general aviation airport—which means a corporate airport—so all these big companies could have corporate jets and fly into the middle of Nassau County. Newsday was trying to prove that influence was being used by the developers and big corporations on the FAA, but the paper wasn’t having success in doing that. So I was in the city room on a Saturday afternoon and the phone rings. It’s a guy from the FAA. He said, “I know that what you’re doing is right, and if you want to be able to prove it, I’ll let you. Just send someone down here…there’s no one here but me.”

EDGE: So this story fell into your lap.

RC: Yes, totally out of nowhere. It was the weekend of the Newsday picnic, and everybody went except basically me.

EDGE: Did you try to contact anyone?

RC: I called all the editors. Everyone was away; everyone was at this beach. Finally, I get some editor who tells me I’ll have to go myself. Well, I had never done anything like this before. So I drove down and the guy let me in, and he basically pointed me to a couple of file cabinets. He said, “Those are the things you want to look at.” I didn’t go home—I worked all that night and all the next day, and wrote a memo for the editors on what I had found. The Monday morning after this, Alan’s secretary calls early in the morning and says, “Alan wants to see you.” Alan had never said a word to me. All the way driving in I was thinking, I’m going to be fired…I’ve got to keep my head up. When I get to the doorway, I see he’s reading the memo about what I found in the files. He looks up and he says, “I didn’t know someone from Princeton could go through files like this. From now on, you do investigative work.”

EDGE: Is it something you’d wanted to do?

RC: Yes, but you say it like I planned everything out. That’s an exaggeration. I knew that what I wanted to do was politics. What I wanted to do was find out how politics really worked.

EDGE: You’ve told me in the past you worked for a county Democratic organization in New Jersey in the 1950s? Did that experience spur your interest in politics?

RC: It did. I graduated from Princeton in 1957 and got married the day after I graduated. We went on this honeymoon for two months, driving around the country, and got back somewhere around Labor Day. I went to work on a paper in New Jersey that was tied in with the Middlesex County and New Brunswick political machine. It almost sounds funny—their chief political reporter would be given a leave of absence for every election so he could write speeches for the Middlesex County Democratic organization. He had a heart attack, so he couldn’t work for a while. He wanted to make sure he had this speech-writing job when he came back, so he wanted to be replaced as speechwriter by someone who was no threat to him. So who better than this kid from Princeton? That’s why I got the job. There was an election coming up and Joe Takacs was the political boss of the city of New Brunswick—a guy who ruled that city with an iron hand. I really did get a look at politics because he really liked me, and he took me with him everywhere. But then the following thing happened. On election day, he did what I later found out was called “riding the polls.” His regular driver took off, and a police captain was the driver for the day. We drove around in this big black car from polling place to polling place. At each place a police officer—a lieutenant or a captain—would come over to the car and basically say that everything was in order. Then we got to this one place where there was a commotion going on between a group of black people and police officers. This [police officer] came over to the car and said something to the effect of, “We’ve had trouble here, but we’re taking care of it now.” I looked over, and they had brought two paddy wagons, and there was a bunch of policeman herding these neatly dressed men—ties and jackets—and young women none too gently into the paddy wagons. They had been trying to be poll-watchers, to make sure the voting was honest, so they had to be gotten rid of.

EDGE: How long did you stay on after seeing this?

RC: When this happened right in front of me, a number of things got to me. It was the meekness with which they were taking this treatment—as if it was expected and they were resigned to it, and I couldn’t stand it. I knew in that moment that I didn’t want to be in the car; I wanted to be out there with them. So the next time the car stopped I just opened the door and got out. I didn’t know it then, but my interests were coming more and more to politics, and more and more to how politics really work. I wouldn’t say I was interested in investigative journalism—I was interested in understanding how politics really worked. And then this [story] happened at Newsday, and Alan said to me, “From now on, you do investigative work.” With my usual savoir faire in moments like this, I said, “But I don’t know anything about investigative journalism.”

EDGE: I’m sure that’s what he wanted to hear.

RC: Well, he said, “I’ll sit you next to [Robert] Greene,” who was a great investigative reporter, and he taught me a lot. And Alan taught me a lot. I learned a lot of things that a lot of reporters never learned. I know how to go through court papers. I know how to trace land transactions. I learned that all from them. I was getting a lesson every day. I learned things then that have guided me all my life, and the simplest thing is: Turn every page. I was going through some files, and I asked Alan some advice about something, and I’ve never forgotten: He said, “Never assume a damn thing. Turn every page.” That has guided me through my whole life.

EDGE: You mean to be thorough, to make sure you don’t miss anything.

RC: Yes. You don’t assume. You never know what’s going to be on a piece of paper. When you get to the Lyndon Johnson Library, the first two floors are a museum. Then you come around the corner and there is this marble staircase. And here are Lyndon Johnson’s papers…there’s four floors of them. They go back—I keep wanting to measure this—it’s like hundreds of feet. The last time they counted, they said there were forty-four million documents, so you couldn’t possibly turn every page and read every page. You’d have to have many lifetimes to do it. My first book [on Johnson] was going to be almost all on his congressional period. So while there were thousands and thousands of boxes, the number of boxes that had to do with the congressional period was manageable—there were 349 boxes. I thought if I was doing what Alan taught me, I would go through every piece of paper in those boxes. It would probably take about a year and a half or something, but you can do it. And by doing that, I found out all these things that people thought could never be found out. All the biographies—there were already a lot of Johnson biographies when I started—they all sort of knew that Brown & Root, this big Texas contracting firm, had financed him. And everyone said, Well, we can never find out about it because no one would talk about it. But I said, “If I’m going to do this, I’m going to do this the same way I was as a reporter—I’m going to turn every page.” And in some file—whatever the file was, it didn’t seem to have anything to do with this—there was this telegram from George Brown, an actual telegram from George Brown to Lyndon Johnson in October, 1940 saying, Lyndon, the checks are on the way.

EDGE: How many years have you spent on Lyndon Johnson now?

RC: I started in 1976.

EDGE: I imagine that immersing yourself in one person’s life for that long must give you incredible insight into who that person is—which is something that I don’t think you could get from being a journalist. Is that something you were seeking, or is that something that just happened based on the nature of your work?

RC: That wasn’t something I was really interested in, in the beginning.

EDGE: Do you feel as though it’s something you have come to appreciate?

RC: If you spend that much time with someone, you feel like you know them. My interest is not telling the life of a great man.

EDGE: It’s in political power?

Robert and Jesse Caro. Never turn your back on grandpa!

RC: Yes, but you immerse yourself, and when Johnson is doing something, you say to yourself, “Well now he’s going to do something.”

EDGE: The way you might with a friend or a close acquaintance?

RC: A really close acquaintance that you’ve spent a lot of time with.

EDGE: Have you found that LBJ’s political life reflected his personal life? Or was Johnson a different person at home than he would have been in the White House or Congress?

RC: Johnson—I can answer quickly—he was the same person.