If you feel as if you’ve seen Leslie Bibb “in everything,” there are two reasons why. There is very little she has not accomplished in film and television, and she possesses a rare talent for lighting up a scene whenever she steps in front of the camera. And no one is better at getting a laugh. After a successful modeling career, Leslie rocketed to stardom as the star of the WB comedy-drama Popular and raised the bar higher yet with a tour de force as Carley Bobby in Talladega Nights. Her film work includes the Iron Man franchise, Law Abiding Citizen, No Good Deed, Tag, The Lost Husband and a sneaky-smart dark comedy called Miss Nobody. Her TV credits number in the many dozens, including memorable turns on ER, Crossing Jordan, GCB and American Housewife. In God’s Favorite Idiot, she played Satan and in Jupiter’s Legacy she played a superhero mom. Needless to say, Leslie does not shrink from a challenge. She sat down with Gerry Strauss for an energetic, wide-ranging discussion About My Father and Palm Royale. of her life and career, and her two newest projects,

EDGE: When you were growing up, were you thinking about a life in modeling and entertainment?

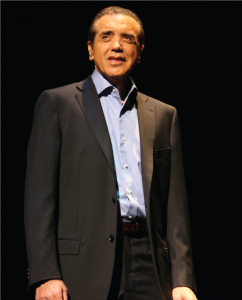

LB: Being from Virginia and growing up in a very country sort of town, it still seems crazy to me. I was coming out of a movie theater with Sam [Rockwell], and he said, “Cookie, there’s your poster.” I walked over and I looked at it and I just saw like, Sebastian Maniscalco, Robert De Niro, Leslie Bibb. And I was like, What? It’s surreal. Growing up, I wanted to get into the  University of Virginia and thought I might go into politics, because I was a page in the General Assembly and my mom ran campaigns. Later, she was the Director of Consumer Affairs for the Commonwealth of Virginia. I thought I wanted to be a lawyer and sort of segue into politics. I won this contest on Oprah Winfrey and it changed the trajectory of my life. My father had died when I was quite young and my mom raised me and my three older sisters. We weren’t a family that traveled. Before my mother and I moved to Richmond, we lived in Lovingston, which was such a country town—like if you needed new sneakers, you had to drive 35 miles to Charlottesville. Our big thing was we went to Virginia Beach. One time we went to Disney World. Suddenly, I was traveling to Europe. It was definitely wild. [Laughs] I’m grateful and feel like something in this lifetime I did right. It feels good.

University of Virginia and thought I might go into politics, because I was a page in the General Assembly and my mom ran campaigns. Later, she was the Director of Consumer Affairs for the Commonwealth of Virginia. I thought I wanted to be a lawyer and sort of segue into politics. I won this contest on Oprah Winfrey and it changed the trajectory of my life. My father had died when I was quite young and my mom raised me and my three older sisters. We weren’t a family that traveled. Before my mother and I moved to Richmond, we lived in Lovingston, which was such a country town—like if you needed new sneakers, you had to drive 35 miles to Charlottesville. Our big thing was we went to Virginia Beach. One time we went to Disney World. Suddenly, I was traveling to Europe. It was definitely wild. [Laughs] I’m grateful and feel like something in this lifetime I did right. It feels good.

EDGE: How did you get involved in the modeling contest?

LB: My sister Trish called my mom and said, “Hey, Oprah Winfrey is sponsoring this model search. You should take a couple pictures of Leslie and send them in.” My mom shot a whole roll, but she wasn’t a good photographer, so there were literally two that weren’t, like, a blur. She sent them in and I was one of 63 girls picked out of 6,000. Wow! Then we got narrowed down to 20. They flew us into Chicago for the weekend and we filmed an actual Oprah Winfrey Show. It didn’t even make sense to me…it felt like I was living a fairytale. And then I won! It was crazy. That summer I went to Japan and started modeling at 16. I was able to start paying my own way, which was a really nice thing for my mom, who’d been pretty selfless with us. Then I fulfilled the dream of getting into UVA.

EDGE: But you left college as a freshman. Was that a difficult decision?

Tina Turnbow

LB: In high school, I could go to New York and do a catalog or a 17 Magazine shoot and miss a week of school. I couldn’t do that in college. That first semester, I couldn’t find the balance between the two. I was walking back to my dorm on a Saturday night after a fraternity event where I saw some [disturbing stuff] happen and something crystallized and I realized I had to abandon what I thought I was going to do my whole life, leave college and go to New York. I just kept telling myself, You have a job and we’ll see what happens. That Monday, I went into the dean’s office and I asked for a leave of absence. I called my mom and to her credit, she was great. I said, “It’s only a semester. I’m only taking off a semester [laughs]. I swear.” UVA was a really good school and I worked really hard to get into it my whole life. Every time you studied and every time you did something it was to get into this school. And then to abandon that for something so weird like going to New York to be a model? I knew I wasn’t going to be a big model, like those girls you see walking around town. I’m not that pretty. I’m not that tall. I’m not special in that way. But I moved to New York on January 5th and I’ve never looked back. I’m so in love with the city, even when it makes me crazy. The minute I got here it made me feel like I was home. I mean, I remember when I was 16 in the model apartment that Elite had me in, looking out the window and just being in awe of it. So it feels to me like a warm hug, New York City.

EDGE: Were you acting at this point?

LB: Our high school didn’t have a big arts program and I just wasn’t hip to it. So, it wasn’t like I always knew I wanted to be an actress. But now, when I look back, I’m like, Oh, comedy—of course! It makes sense to me because all I was doing was watching Carol Burnett and Tracey Ullman as a kid. Yeah. I didn’t understand what was seeping in at the time. Within a year of moving to New York, I found acting and the minute I walked into the Maggie Flanigan Studio it just went great. I was like I’m with my people.

EDGE: Your first recurring character was Brooke McQueen on the WB series Popular, which brought a whole new level of attention. How did you process that?

LB: This is pre-Twitter, pre-Instagram so [television] was the world. It was a very sort of G-rated popularity, you know what I mean? People were still kindhearted and not troll-y. I look at young actors now who are coming up and I really feel for them, because it was kind of Utopian. You went to the Nickelodeon Kids Choice Awards or the Teen Choice Awards. It was exciting and cool and wonderful.

EDGE: Was the success of Popular validating for you, not getting the immediate feedback of social media that you have now?

Dan Anderson/Lionsgate

LB: It was validating but you know what’s funny? I didn’t really feel that while we were filming Popular. I feel it more now. I would say once a week somebody stops bullets just bounce off of you. me and goes, “I loved you in Popular!” Carly Pope, who played Sam McPherson on the show and is still like my sister—we’re forever tethered to each other [laughs]— I don’t think we realized what was happening or the impact we had. We were kids, you know, and you think, Oh, this happens every day. You get to be the star of a show every day. And then the show goes away and you’re like, Oh no, now I’m just a working actress who has to hustle for another job. But you’re such a kid. You’re just like, I can do anything. Yeah. What’s next? Back then, remember, you had pilot season. You didn’t have all the streamers. There was NBC, ABC, CBS, Fox and the WB was like the new channel. So yeah, it was just really exciting. You’re made of Teflon at that age;

EDGE: In Talladega Nights, you’re hilarious, you’re in the room holding your own with Will Ferrell, John C. Reilly…

LB: …Molly Shannon, Sacha Baron Cohen…

EDGE: Yes, so here’s the question. Sometimes actors in a situation with established comic legends are there to kind of have that hilarity bounce off of them. You were in a situation where you had to volley back and give as much as you got. What’s the key to walking in there and pulling that off?

LB: Thank you for saying that. Thank God I studied acting! I looked at Carley Bobby and just knew who she was. I had her so crafted in my mind and I was so rooted in that character. Don’t get me wrong. In the audition with Will, when I had to screen test with him, my hands were shaking before I went in. But I’d strung these pearls and I came in with a beer can. Will was improvising, and then I improvised something about my pearls. [Director] Adam McKay asked, “What was that?” And I said, “I feel like Carley is the star of her own Country & Western love song [laughs]. I feel like her mama told her that pearls make you a lady, so she always wears pearls.” To Adam and Will’s credit, they made that playing field so easy. They give you a ball, they give you a bat, they give you a mitt and they say, Let’s go!

EDGE: What did you take away from that film about improvisation? Clearly there was a lot of that happening.

Upper Case Editorial

LB: Adam once said, “Never sit on an intention. Even if you say something and it goes south, it’s not that the improv is wrong, it just falls flat. There could be something that we hit on that could lead to something great.” It really was the best piece of advice because it is something I carry through in all my work. And I try to—whether it’s a comedy or not—just trust my instinct. Which can be hard sometimes if you have a director that’s sort of diminishing you or making you not feel safe, to remember to do that. But you must do that as an actor. Never, ever sit on your intention if your instinct is pulling you somewhere. Go with it.

EDGE: Do you consider that your signature role?

LB: I do. I think it would be Carley Bobby. I don’t think I knew that I could do that. That was the game-changer for me, in terms of believing in myself and trusting my instincts.

EDGE: You played reporter Christine Everhart in Iron Man, the very first movie in the Marvel Universe, and continued in that role on-screen and in voiceovers. How do you process the success of that franchise?

LB: In addition to being part of these movies that people watch and stream every minute of every day, I’m most proud of Iron Man because I think—not because I’m in it—out of all of those movies, Iron Man is the best and the most well-made. I remember when we were filming it, Jon Favreau saying to me, “I feel like we’re shooting the most expensive independent film ever.” Remember, Robert Downey Jr. was not Robert Downey Jr. yet. It was a big deal but it did feel like an independent film. It was not super cool, not this big, polished thing—even though it was very polished and very cool. What changed me was getting to see people like Robert and Gwyneth Paltrow work, and to work with Jon, who is one of my favorite directors because he is a great actor, which makes him a brilliant director. I did good work and I’m proud of it.

EDGE: This year, you’re in About My Father, a comedy with acting legend Robert De Niro and one of the hottest standups, Sebastian Maniscalco. With everyone coming from different directions, how did you go about creating chemistry?

Tina Turnbow

LB: Okay. So I think chemistry is something you never know if it’s going to be good or not good. Luckily, we all had great chemistry and were fortunate enough that somehow that chemistry was translated to film. ’Cause sometimes you feel like it’s happening, but then it falls flat. It’s this weird thing. You can feel alive when you’re filming it, but then when you see it, you’re like, Where is it? Maybe the director filmed it in a weird way. Maybe the editor did something. Luckily, everything that felt so great when we did it in 2021 in Mobile, Alabama, when I saw it, I was like, Oh, it’s on screen! The chemistry comes from David Rasche, Kim Cattrall, Anders Holm, Brett Dier, Sebastian (above) and Bob and myself. Everybody knew who their character was. Everybody had a very strong idea of what they were doing. If we started improvising something, our wonderful director Laura Terruso was always game. Her mom is Sicilian, so she knows this world and she was the best captain of a ship we could have had. She navigated this whole course for us. And you know, Sebastian and Austen Earl wrote a great script and I think it was on the page. Sebastian did an incredible job being number one on the call sheet and being the lead of a movie, which he’d never done before. He was a wonderful partner in crime. And I love Ellie, the character I play. I love her optimism and her indomitable spirit.

EDGE: Your other release this year is the Apple series Palm Royale, a comedy starring Kristen Wiig that features Carol Burnett in an impressive cast.

Dan Anderson/Lionsgate

LB: I love Kristen Wiig so much and I feel like I grew as an actor, leaps and bounds, getting to watch that woman work. Carol Burnett is so awesome. It’s like crazy to me. Allison Janney, I mean, who doesn’t love Allison Janney? Laura Dern who’s just…I want a cup of whatever Laura Dern is drinking in life. God, she’s such a force. Ricky Martin, Josh Lucas, me— it’s 1969 Palm Beach, Florida and my character’s just insane. I had never gotten to do something quite like this before. The show is quite big and I’m really proud of it. Most of my stuff is with Kristen; we’re sort of each other’s nemesis.

EDGE: You’ve done so much in film and television, what’s out there that intrigues you as something different you’d like to do?

LB: I’ve always wanted to do a Western because I love riding horses. But I really want to direct, so that would be the next hat I’d want to wear, the next thing that I want to do for myself. Direct on a horse, maybe! But no, direct. I think that would be an incredible challenge.

Editor’s Note: Leslie Bibb’s decision to leave college and launch her career as a model and actress turned out to be a good one. To get the truth about this moment of truth, check out the extended version of her Q&A at edgemagonline.com.

EDGE: How difficult is it to assemble a cast like the one in The Shield?

EDGE: How difficult is it to assemble a cast like the one in The Shield?

inspiration, New Jersey serves as his touchstone. The instant he motors past that center stripe in the Lincoln Tunnel, he feels he is home again. In his chat with the NBC Nightly News anchor, EDGE editor MARK STEWART discovers that what you see (and hear) is what you get. Whether getting a story right, hosting Saturday Night Live, or putting his money where his heart is, Williams is as authentic as they come.

inspiration, New Jersey serves as his touchstone. The instant he motors past that center stripe in the Lincoln Tunnel, he feels he is home again. In his chat with the NBC Nightly News anchor, EDGE editor MARK STEWART discovers that what you see (and hear) is what you get. Whether getting a story right, hosting Saturday Night Live, or putting his money where his heart is, Williams is as authentic as they come.

BW: When I pass into New Jersey there’s something that happens to me at mid-span on the GW Bridge and midway through the Lincoln Tunnel. I call it my ‘power corridor’. I feel most at home there. I speak New Jersey. New Jerseyans are real. It’s the most densely populated state in the union and yet I can tell from your accent if you’re from South Jersey or North Jersey. I can usually tell if you’re from the Mid Shore. We have a lot of different regions, and yet I think there’s a baked-in pride. We have to put up with a lot of crap. I don’t take kindly to a lot of Jersey jokes because I know a lot about my state. Way too many people judge our state based on one stretch of highway on the Turnpike along refinery row. And that’s unfortunate. I think if we had it to do over again, we wouldn’t route so many millions of motorists right past the most heavily industrialized region of the East Coast.

BW: When I pass into New Jersey there’s something that happens to me at mid-span on the GW Bridge and midway through the Lincoln Tunnel. I call it my ‘power corridor’. I feel most at home there. I speak New Jersey. New Jerseyans are real. It’s the most densely populated state in the union and yet I can tell from your accent if you’re from South Jersey or North Jersey. I can usually tell if you’re from the Mid Shore. We have a lot of different regions, and yet I think there’s a baked-in pride. We have to put up with a lot of crap. I don’t take kindly to a lot of Jersey jokes because I know a lot about my state. Way too many people judge our state based on one stretch of highway on the Turnpike along refinery row. And that’s unfortunate. I think if we had it to do over again, we wouldn’t route so many millions of motorists right past the most heavily industrialized region of the East Coast.