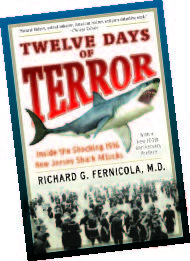

Author of Twelve Days of Terror: A Definitive Investigation of the 1916 New Jersey Shark Attacks

A century after these infamous attacks, what is known about them and what is still up for debate?

The first attack occurred late in the afternoon of July 1, in Beach Haven. The second occurred on July 6 in Spring Lake. Both victims were men in their 20s and both were killed. On July 12, there were three victims in Matawan Creek, two of whom were killed. The third person survived with serious leg injuries. What is still up for debate is how many sharks were involved, what the species was/were and, ultimately, why this series of ferocious attacks occurred in a place where attacks had never occurred before and haven’t since.

What were those 12 days of terror like for beachgoers?

People didn’t associate the water with dangers—they were more afraid of jellyfish, sharp stones and crabs. So the response to a predator attacking the limbs of bathers and killing four out of five people was what you might imagine it would be today. A shark attack is such a rare occurrence in New Jersey that I refer to the ferocity and frequency of these attacks as an “anomaly within an anomaly.” There was a fear of the unknown in nature and, as a result, there was a great reluctance to venture into the ocean after the attacks.

How did public perception of sharks change?

How did public perception of sharks change?

In 1916, a lot of people in the metropolitan area didn’t know what a shark looked like, or even have a grasp that there were multiple species. If an American bather spotted a shark prior to 1916, it posed as much of a danger as, say, a stray dog—certainly nothing life-threatening. The 1916 attacks baptized us to the potential danger of these predators if you were in the wrong place at the wrong time. The attacks also triggered what was probably the biggest shark hunt in history. People tried to catch and kill any large shark they could. When it became apparent that the attacks had ceased, that response changed.

In the 15 years between the original release of your book and the updated 2016 edition published in May, people have become obsessed with sharks. That’s helpful to you as an author, but how do you explain it?

I will say I’m very, very surprised at the response to films like Sharknado. I’m even surprised by the perpetual interest in “Shark Week.” I believe that it’s a combination of things, including the growth of social media and the immediate news feeds that give you reports of shark attacks from very distant lands. You also, over the last 20 or 30 years, have an increase in wholesome and accurate education about sharks to a whole new generation of young people, mostly through aquariums and research programs. I hate to use the word “sinister,” but there is something diabolically mysterious about the general appearance and stealthy maneuvering of sharks that continues to fascinate people.

So this summer, when people take Twelve Days of Terror to the shore, is it safe to put it down and go in the water?

Yes. Reading about attacks can sensitize you to the dangers of sharks, but that is completely unfounded, especially as it relates to New Jersey. The rarity of attacks in New Jersey should actually encourage someone to go in the water.

Editor’s Note: Richard G. Fernicola is a physician specializing in post-stroke and post-injury recovery. The 2016 edition of Twelve Days of Terror is published by Lyons Press and hit store shelves in May.