The ups, downs, ins and outs of raising a child who is probably smarter than you are.

By Jim Sawyer

Over the past few decades, the validity of IQ scores has taken a beating. For all that number does say, there is an awful lot it doesn’t. For better or worse, however, we are a score-keeping society, thus we continue to honor high IQs. For the record, a young person with an IQ of 125 or above is considered to be “gifted.” This is no guarantee of success in life, but it is strongly indicative of a complex, fertile intellect.

If you happen to be the mother or father of such a child—or suspect that your child is gifted—you know that parenting is anything but easy. Nor, in many cases, is recognizing your child’s “giftedness” in the first place.

Indeed, high-intellect kids don’t all act or think or look the same. They do not always stand out from their peers in obvious ways; often when they do, it is for behavior that is negative rather than positive. The National Association for Gifted Children—a Washington DC-based organization dedicated to supporting families and teachers of gifted and talented kids—points out that 60 percent of gifted five-year-olds already know nearly all of the material taught in kindergarten the day they walk into the classroom. A bored five-year-old can easily become disruptive.

What qualifies a child as gifted? He or she is able to reason and learn at a high level from an early age, demonstrating proficiency in math or music or language. You’ve probably encountered a three-year-old with a broad vocabulary who speaks in long, complete sentences (with grammar that’s as good or better than yours). This is a major tip-off. Sometimes, however, giftedness in a young child is more noticeable in the physical realm, such as artistic talent or athletics. Either way, gifted children almost always learn faster than their peers and perform better in testing and on exams. Because they deal with a larger and ever-changing “sample size” of students, educators—particularly classroom teachers—are often the first to notice a gifted child. It’s not always news to the parents, however it is gratifying to have their suspicions confirmed.

What happens from that point—how development is encouraged and accelerated through childhood, adolescence and young adulthood, and how certain obstacles are eliminated along the way—will determine how a kid’s gifts manifest themselves in later life. So, hey. No pressure, right?

School is tremendously important. Or, perhaps more to the point, education is tremendously important. Finding a school with a “gifted” program is a start. But not all programs are created equal. Ideally, gifted children will be exposed to a wide range of educational experiences (both in and out of school) at a young age and, then, as they grow older, more of a focus on the areas in which they show the most promise. A good gifted program will be nimble enough to keep adjusting to a child’s capabilities, while also pointing parents to outside resources and programs that will keep nourishing his or her intellect. Parents need to stay on top of their gifted child’s progress, taking advantage of whatever assessments are offered and being open to suggestions and even criticism. Indeed, parent education is a huge part of the process.

www.istockphoto.com

What if your son or daughter has not been identified as gifted, but you are convinced he or she is? Actually, this is not all that unusual. Not every elementary school (and not every elementary school teacher) is equipped to spot giftedness. In many cases, this type of evaluation won’t even be made until your child is six or seven, particularly in a public school environment. If you suspect your three-year-old is miles ahead of the competition, go get him or her independently tested. The sooner you can evaluate needs and opportunities, the better off your child will be.

That is doubly true for children who exhibit early social or behavioral problems, or who are hyper-focused on a single area of interest (e.g. being able to name 100 dinosaurs). While these can be signs of giftedness, they may also be early indications of ADHD or Asperger’s. IQ testing is one way to avoid a misdiagnosis. A gifted child who underperforms in the classroom may not be connecting with the teacher, or be bored or disorganized. But he or she may have an attention deficit issue, too. Both can be true. Testing will usually solve the mystery, but it is up to the parents to push for that; the school may see a lackluster student and never think to do any screening.

www.istockphoto.com

What Now?

Once your gifted child has been identified and you’ve found programs and resources that will feed his or her intellect, the rest is easy, Mom and Dad. No…just kidding. Your work as a parent actually has just begun!

Consider, for instance, the fact that gifted children sometimes act their age. Their minds may be careening into adulthood, but their bodies and emotions are always playing catch-up. It is not unusual for incredibly able and mature kids to melt into disabling temper tantrums over the tiniest things. They are under constant pressure of one kind or another, and often suffer from severe anxiety—without being able to articulate their frustration. This is only exacerbated by bouts of disorganization and by a feeling of isolation from their peers. A high-functioning mind is rarely a peaceful one. Constant love, support, understanding and recognition are a must. A little courage doesn’t hurt, either.

Ironically, the best bits of advice for parents of gifted children may be the most counter-intuitive. Parents who push or overschedule their gifted child, or who defer to them on big decisions, are likely to do more harm than good. On three specific points—all don’ts—there is strong consensus among educational and developmental health experts:

- Don’t push for perfection. Good grades and scores are not a measure of success for a gifted child. Encourage your gifted child to develop and pursue multiple interests at whatever pace makes sense to them. Voracious learners will learn voraciously without parent reminders.

- Don’t confuse challenging your gifted child’s mind with keeping the child constantly busy. Maintain a reasonable schedule with lots of downtime. When a gifted child is “doing nothing,” the kid’s brain is still percolating.

- Don’t let your gifted child call the shots. You are the grown-up. You make the important decisions.

Go ahead and add to “that Don’t make your gifted child an example for your other kids.” Rather than elevating the performance of siblings, this is more likely to lower the performance of the gifted child, who might choose to “dumb down” in order to fit in with brothers and sisters.

Friendly Advice

Finally, parents of high-intellect kids should understand that their child may need help or encouragement forming social connections. This is really important. Popular culture tells us gifted kids are nerds or geeks who naturally isolate themselves from others. This is untrue. Gifted children play sports and perform on stage and get into all kinds of mischief. They want to fit in with schoolmates as much or more as they do with their siblings.

Ask a gifted child what he or she wants most in the world and the answer is likely to be “a friend.”

Often, a gifted child will seek friendship from an older child who is at a similar stage of emotional maturity. Interestingly, this is often misinterpreted as a lack of maturity, which is 180º wrong. A study by the Davidson Institute for Talent Development concluded that intellectually gifted children start looking for friendships based on closeness and trust at an age when their classmates are still looking for play partners. Naturally, they gravitate toward older kids. This gap narrows by the end of elementary school, but the intervening years can be isolating. The study’s author, Miraca Gross, suggests that parents actually discuss the hierarchy of friendship conceptions with their gifted children:

“Because gifted children begin to make social comparisons earlier than their age-peers, they can become acutely aware that they seem to be looking for different things in friendship than are their age-peers. A frank but sensitive discussion of this can help ameliorate the feelings of ‘strangeness’.”

Gross adds that high-intellect children tend to prefer one or two close friends to being part of a larger friend group:

“It’s okay if your gifted child prefers to link with one ‘special’ friend rather than ‘play the field.’ Parents sometimes worry that the child seems to be putting all his or her friendship eggs in the one basket—but we must remember that because the quality of gifted children’s friendships is different, they have an earlier need for the exchange of confidences and the discovery of mutual bonds. This is more easily achieved in pairs than in larger groups.”

www.istockphoto.com

If you are the parent of a gifted child, good research and advice is available on a wide range of topics, both online and on bookstore shelves. Several organizations have dedicated themselves to maximizing the brainpower and mental health of high-intellect kids, and most elementary schools do employ someone who can spot a superior student who has somehow slipped under the radar through nursery school and kindergarten. If you suspect your child is gifted, these same resources can point you toward the kind of testing and expertise that will let you know for sure.

www.istockphoto.com

Summer Solutions

According to the National Association for Gifted Children, even the brightest kids can backslide academically during an unstructured summer. The solution for many is an overnight camp experience. Parents of gifted children face some challenges finding the right fit, however. The boxes you’ll want to check (and, frankly, this goes for parents of every child) include:

- Good balance between academic, physical and social activities

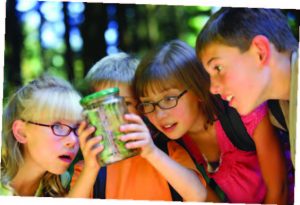

- Active, hands-on learning vs. passive learning

- Exploring areas beyond what a child is learning in school

- Progress assessments at the end of a session

- Staff trained to address intellectual and emotional needs

According to Dr. Denise Drain, who consults on gifted programming strategies, professional development and program review, a good summer program should build on children’s interests and expertise.

“They may give children and adolescents an opportunity to develop expertise in areas such as sports, visual and performing arts, music, and academics,” she maintains, adding that being engaged in their own learning “increases motivation and helps children to develop goals and positive attitudes toward their abilities.”

There are a number of exceptional residential summer camps within a day’s drive of New Jersey, which make use of high-end college facilities. If you are in the market, these might be good starting points:

Summer Institute for the Gifted • Bryn Mawr, PA

Residential students live in dorm groups of a dozen or so, with four-period academic days and special trips and programs on the weekends. Classes are comprised of students in the same age- and talent-range.

The Center for Talented Youth • Baltimore, MD

This organization has a summer camp program for gifted children at Johns Hopkins. The three-week sleep-away programs begin in 5th grade and offer courses in the humanities, sciences, math, writing, and computer science.

Duke University Summer Camp • Durham, NC

Duke’s youth summer programs encompass math, science and engineering, but also offers creative writing and performing arts for gifted campers. The programs run for about two weeks, again starting at 5th grade.

Black Book Partners

Clearing the Bar

Which public figures just cleared the 125 IQ gifted threshold? Vladimir Putin tested at 127, while President Lyndon Johnson was a tick lower at 126. Also at 126 are NFL quarterbacks Tom Brady (right) and Steve Young. Right at 125 are guitar virtuoso Eddie Van Halen, along with actors Chris Pratt, Tom Cruise and Mira Sorvino. Who fell just short of gifted status? Among public figures who tested at 124 were President George W. Bush, X-Men actress Famke Janssen and serial killer Ted Bundy.