Eight incredible tales of wilderness survival.

Nothing is more terrifying than a wilderness survival situation. In one jolting moment, you are torn from safety and security and thrown into profound peril. You are alone, with little more than your wits and endurance keeping you alive. It’s the stuff of nightmares. And, of course, the stuff of movies and television. Think Tom Hanks in Cast Away. Or James Franco in 127 Hours. Or, if you’re a reality TV fan, Naked and Afraid. The theme of man- or woman-against-nature is as old as literature.

Older, in fact…hear me out.

I believe it’s a part of our basic biology. Think about it: We all are descended from at least one individual who found himself or herself alone in the wild, possibly left for dead, and then somehow beat the odds and made it back to safety. That little speck of DNA that survived along with that person has been passed down through a dozen or a hundred or a thousand generations—to me, to you, to all of us. Which is why our curiosity is triggered and our adrenaline begins to surge when we see or hear or read about someone who defies the odds and stumbles out of an impenetrable jungle or washes up on a distant shore.

One of the most enduring survival stories in the annals of popular fiction is Robinson Crusoe, the tale of a shipwrecked traveler who spends 28 years on a relentlessly hostile island somewhere in the Caribbean. The book was first published in 1719 and was an immediate sensation. Many readers believed it to be a real-life account and wondered how they might fare in similar circumstances. This was a new genre, “realistic fiction,” and author Daniel DeFoe had clearly tapped into that primal wiring all humans share. Although the plot details of Robinson Crusoe leaped from the fertile imagination of DeFoe, the inspiration for the title character almost certainly came from the incredible tale of Alexander Selkirk, our first of eight remarkable survival stories.

ALONE ON AN ISLAND

Selkirk was a 20-something Scottish privateer during the War of Spanish Succession, a conflict that embroiled all of Western Europe and its colonies in the early 1700s and helped England become a world economic power. Selkirk’s impulse control left much to be desired. He actually had chosen a life at sea over showing up in court to face charges of “indecent conduct in church.” In 1704, he was serving aboard the Cinque Ports in the Pacific, fighting French ships and plundering Spanish mining settlements in South America. When his captain, Thomas Stradling, overloaded the leaky ship on a resupply stop in Mas a Terra, an uninhabited island off the coast of Chile, Selkirk insisted he would not sail unless much-needed repairs were made. Captain Stradling took the unruly Selkirk at his word and abandoned him on the island with a musket, hatchet, knife, cooking pot and Bible. The Cinque Ports sailed away…and soon sank.

resupply stop in Mas a Terra, an uninhabited island off the coast of Chile, Selkirk insisted he would not sail unless much-needed repairs were made. Captain Stradling took the unruly Selkirk at his word and abandoned him on the island with a musket, hatchet, knife, cooking pot and Bible. The Cinque Ports sailed away…and soon sank.

Selkirk set up camp on the beach, living off lobsters and waiting for another ship to sail by. His first of many rude awakenings came during mating season for thousands of sea lions, which chased him off the beach and into the island’s interior. There he lived off wild turnips and cabbage, as well as feral goats, when he could catch them. Unfortunately, Selkirk found himself plagued by rats, which attacked him every night after the sun went down. He solved this problem by using goat milk and meat to domesticate wild cats that lived on the island. They kept the rodent population at bay. Two ships did show up, but both were Spanish. One spotted him and sent ashore a landing party to capture him. Had they been successful, Selkirk would likely have been executed.

Four years and four months after being marooned, Selkirk was finally rescued by an English privateer and went back to his plundering ways like a man making up for lost time. Still an impetuous risk-taker, he was given command of his own ship and enjoyed several successful forays into Spanish territories. He made enough to retire comfortably in London, and his story made him something of a celebrity there, but soon Selkirk grew restless and he joined the Royal Navy, probably to avoid the long arm of the law or some other offended party. He lived an eventful life and was buried at sea after contracting yellow fever at the age of 45.

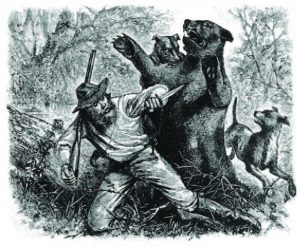

BEAR NECESSITIES

Another familiar story inspired by a real-life tale of survival is The Revenant, the 2015 film starring Leonardo DiCaprio. A “revenant” is someone who has been revived from death. Leo plays Hugh Glass, a frontiersman who, while serving on a westward expedition in 1823, was badly mauled by a grizzly bear in current-day South Dakota. He managed to kill the bear before losing consciousness, but suffered  what appeared to be mortal wounds. After dragging the unresponsive Glass on a litter two days, the expedition’s leader decided he was slowing down their progress and assigned two members of the party to stay with him until he died. While the two men waited for the inevitable, they dug a shallow grave. When the inevitable didn’t come quickly enough, they stripped Glass of his valuables and placed him in the hole they had dug. When the men caught up with the expedition they dutifully reported the sad news of their companion’s demise.

what appeared to be mortal wounds. After dragging the unresponsive Glass on a litter two days, the expedition’s leader decided he was slowing down their progress and assigned two members of the party to stay with him until he died. While the two men waited for the inevitable, they dug a shallow grave. When the inevitable didn’t come quickly enough, they stripped Glass of his valuables and placed him in the hole they had dug. When the men caught up with the expedition they dutifully reported the sad news of their companion’s demise.

You probably know the story. Glass awoke sometime later to find himself alone and under the skin of the bear that had attacked him—with a broken leg and deep, festering wounds. He set his own leg and allowed maggots to feast on his dying flesh in order to prevent gangrene. He survived on berries and roots. Glass dragged himself to the Cheyenne River, made a crude raft, and floated down to Fort Kiowa—a six-week journey covering 200 miles. After recovering from his injuries, Glass set out to exact murderous revenge on the two men who left him for dead.

Glass caught up with one of them, a teenager named Bridges, where the Bighorn River empties into the Yellowstone River. Seeing how young Bridges was, he decided to spare him. He found the second man, named Fitzgerald, in Nebraska. Fitzgerald had joined the army and was stationed at Fort Atkinson. Knowing he would be executed if he killed a U.S. soldier, Glass spared Fitzgerald, too, but warned him that he had better make the military a lifelong commitment—because the day he left the army he would end him. Glass never got the chance. He returned to frontier life and was killed during a skirmish with an Arikira war party. If you haven’t seen The Revenant, don’t worry about spoilers here; the movie is what they called a “fictionalized” version of the true story.

SNOWBOUND

Jan Baalsrud’s story sounds like it must be fiction. A Norwegian commando fighting for the resistance against Nazi occupiers during World War II, Balsruud and 11 compatriots set out to destroy an airfield control tower in the winter of 1943. Their mission was compromised when they mistook a local shopkeeper for their resistance contact (both men had the same name) and the shopkeeper—fearing he was being tested by the Germans—turned them in. The next morning, Baalsrud’s boat, which was loaded with 100 kilos of explosives, was sunk and everyone except Baalsrud was either killed or captured.

Baalsrud, soaking wet and missing one boot, hid in a snow gully, where he disarmed and shot a Gestapo officer with his own luger. From there, the Norwegian evaded capture for two months, surviving in frigid conditions with occasional assistance from locals. Suffering from snow blindness and frostbite, Baalsrud amputated his toes with a pocketknife to avoid gangrene.

Baalsrud hid from German patrols behind a snow wall for weeks and then was transported by stretcher to the Finnish border. Now near death, he was taken by a group of native Samis by reindeer to neutral Sweden. After months of recovery, Baalsrud made his way to Scotland, where he trained fellow Norwegian commandos. Eventually, he returned to Norway, where he worked as a secret agent until the end of the war. Baalsrud lived to the age of 71. At his request, his ashes were buried in the same grave with one of the partisans who had aided him during his escape from the Nazis in 1943, and paid the ultimate price.

SOUNDS BANANAS

Staying alive in the wild often depends on one’s ability to take advantage of the local animals. Marina Chapman’s spin on this rule of wilderness survival is a jaw-dropper. Around 1960, she was abducted as a toddler and then left for dead deep in the Colombian rainforest when her kidnappers, possibly realizing that her family would be unable to afford a ransom payment, dumped her and drove away. She walked for days, hoping to find a village and crying for help that never came. What she found was a troop of capuchin monkeys, who eventually adopted her. She knew she had been accepted into the group when the monkeys urinated on her leg and, later, when they groomed her and allowed her to groom them. For as long as five years—Marina has no way to say for sure—she lived with the capuchins. During that time, she managed to decipher how they communicated and was able to produce a vocabulary of whistles, coos, chirps and high-pitched screams. She said all they (and she) thought about was what they would eat each day.

By the time Marina was “rescued” by a pair of hunters, she had forgotten how to speak. They sold her to a brothel, where she did housework but managed to escape before being forced into prostitution. She used her “monkey skills” to survive as a street urchin in the town of Cucata before being taken in by a family in Bogota around the age of 14. She decided to name herself Marina after a Colombian beauty queen and eventually went to England as the family’s nanny. She married an Englishman and had a family of her own.

Marina taught her children how to climb trees and liked to tell them bedtime stories about hunting for food in the jungle. Sometimes she’d walk around the yard on all fours. And she could spot a snake from hundreds of feet away. The kids thought she was just being funny until they were old enough to hear the whole story—which Marina struggled to tell because her brain still functioned in a non-linear way. Finally, they encouraged her to write a book, The Girl with No Name. Several publishers turned it down, refusing to believe it could be true. To this day, many doubt Marina’s story. True or not, it’s quite a tale.

FALL GIRL

A jungle survival adventure of an altogether different kind began on Christmas Eve 1971, two miles in the air, when a Lockheed Electra passenger plane was struck by lightning and broke apart, spilling its passenger into the angry sky. Seventeen-year-old Juliane Koepcke, the daughter of German parents working in Peru, was still strapped in her seat when it detached from the fuselage. Her mother, who was sitting beside her, disappeared as the entire row of seats plummeted to the earth.

Koepcke regained consciousness and soon realized she was the only crash survivor. Experts theorize that the row of seats acted as a parachute, perhaps catching an updraft and, in addition, that the jungle canopy must have broken her fall. Even so, she suffered a broken collarbone, deep gashes in an arm and leg, and facial trauma. Koepcke pocketed some candy she found at the crash site and then activated the wilderness skills she learned while growing up in the Peruvian jungle with her father, a biologist, and her mother, an ornithologist. Koepcke found a river and waded downstream in knee-deep water for 10 days before discovering a small boat. She poured gasoline over her wounds to sterilize them and then fell asleep in the vessel. She was discovered the following morning by a group of fishermen, who transported her to the nearest village. Koepcke was reunited with her father, who was stunned to see her alive. She then led the recovery team to the crash site.

Koepcke pocketed some candy she found at the crash site and then activated the wilderness skills she learned while growing up in the Peruvian jungle with her father, a biologist, and her mother, an ornithologist. Koepcke found a river and waded downstream in knee-deep water for 10 days before discovering a small boat. She poured gasoline over her wounds to sterilize them and then fell asleep in the vessel. She was discovered the following morning by a group of fishermen, who transported her to the nearest village. Koepcke was reunited with her father, who was stunned to see her alive. She then led the recovery team to the crash site.

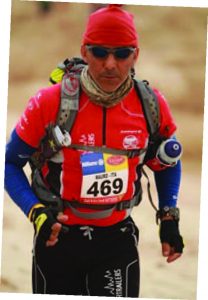

Running on Empty

Have you ever asked your iPhone “Where am I?” If it’s a geography question (as opposed to a career or relationship question) you’ll get an accurate answer that even includes a map. Thanks to GPS and online tools like Waze, getting lost is no longer the terror-inducing situation it was just a generation ago. Mauro Prosperi might be reluctant to admit it, but he really could have used one of those apps. He was competing in the 1994 Marathon of the Sands, a multi-day endurance race across Morocco’s slice of the Sahara Desert when a sandstorm separated him from the pack and left him alone and disoriented. Prosperi thought he was catching up, but he was actually running into neighboring Algeria.

an accurate answer that even includes a map. Thanks to GPS and online tools like Waze, getting lost is no longer the terror-inducing situation it was just a generation ago. Mauro Prosperi might be reluctant to admit it, but he really could have used one of those apps. He was competing in the 1994 Marathon of the Sands, a multi-day endurance race across Morocco’s slice of the Sahara Desert when a sandstorm separated him from the pack and left him alone and disoriented. Prosperi thought he was catching up, but he was actually running into neighboring Algeria.

Out of water and realizing the magnitude of his error, Prosperi grew despondent and attempted to slit his wrists. However, he was so dehydrated that the blood clotted almost instantly. Then he recalled a bit of advice a Berber nomad had offered before the race: When in doubt, walk in the direction of the morning clouds. And so, he set off again. Eating lizards, bugs and cacti, Prosperi made it to a desert oasis and was rescued, 40 pounds lighter than when he had started nine days earlier. He had run, walked and crawled 300 kilometers in the wrong direction.

In 1998, Werner Herzog made the film Wings of Hope, based on Koepcke’s remarkable story. It was a very personal project for the famed director. In 1971, he had been scouting locations in South America and was booked on Koepcke’s ill-fated flight…but missed it due to a last-minute change in his schedule.

WHALE OF A TALE

Just because you can build a boat, it doesn’t mean you should be sailing it by yourself. Steve Callahan, a naval architect and avid sailor, designed and constructed the Napoleon Solo and sailed it across the Atlantic to England in 1981. So far so good. From the port of Penzance, at the extreme southwest tip of England, he joined a single-handed sailing race to Antigua in January 1982. Foul weather off the coast of Spain swamped many of the entries, including the Napoleon Solo, but Callahan made repairs and, though he was now out of the running, decided to complete the journey anyway. One week later, the vessel’s hull was punctured during a night storm in a collision with a whale. Callahan had time to collect a few items, including the book Sea Survival, by Dougal Robertson. He climbed into a six-person life raft and watched his foundering ship drift away.

Just because you can build a boat, it doesn’t mean you should be sailing it by yourself. Steve Callahan, a naval architect and avid sailor, designed and constructed the Napoleon Solo and sailed it across the Atlantic to England in 1981. So far so good. From the port of Penzance, at the extreme southwest tip of England, he joined a single-handed sailing race to Antigua in January 1982. Foul weather off the coast of Spain swamped many of the entries, including the Napoleon Solo, but Callahan made repairs and, though he was now out of the running, decided to complete the journey anyway. One week later, the vessel’s hull was punctured during a night storm in a collision with a whale. Callahan had time to collect a few items, including the book Sea Survival, by Dougal Robertson. He climbed into a six-person life raft and watched his foundering ship drift away.

Callahan’s first move was to activate the raft’s E-PIRB (Electronic Position Indicating Radio Beacon). In 2021, this would lead to a quick rescue. But in 1982, satellites did not monitor E-PIRB signals, and the raft was in the “fat” part of the Atlantic that commercial airliners did not use, so no one else was close enough to detect the E-PIRB. As days turned into weeks, Callahan put Robertson’s words into action. He noticed that a kind of ecosystem developed around his raft and was able to spear or hook a variety of fish. He also created a sun still and other improvised devices that produced a pint of water a day. Callahan fended off sharks, repaired punctures, lost a third of his bodyweight and endured painful saltwater sores for 76 days before drifting to the coast of Guadeloupe.

the raft was in the “fat” part of the Atlantic that commercial airliners did not use, so no one else was close enough to detect the E-PIRB. As days turned into weeks, Callahan put Robertson’s words into action. He noticed that a kind of ecosystem developed around his raft and was able to spear or hook a variety of fish. He also created a sun still and other improvised devices that produced a pint of water a day. Callahan fended off sharks, repaired punctures, lost a third of his bodyweight and endured painful saltwater sores for 76 days before drifting to the coast of Guadeloupe.

After his ordeal, Callahan became a regular contributor to sailing magazines and also designed a lifeboat based on his survival experience. Callahan also wrote the novels Adrift and Capsized. During the making of the 2012 film Life of Pi, director Ang Lee hired Callahan as a consultant to make life aboard a drifting lifeboat more realistic. Callahan fashioned the various fishing lures and other tools that were used by Suraj Sharma throughout the movie.

A FISHY STORY

Callahan called the open ocean the world’s great wilderness. He gets no argument from Jose Alvarenga. An experienced Pacific fisherman, he set out from Costa Azul in Mexico on November 17, 2012 in a 23-foot fiberglass skiff with a big icebox and single outboard motor. His usual fishing partner was unavailable, so he took on a young, inexperienced assistant named Ezequiel Cordoba, whom he had never met before. The two men brought in 1,000 pounds of fish the first day, but a sudden storm prevented them from returning to port. For five straight days, the storm blew them ever deeper into the ocean, destroying the boat’s motor and electronics, and causing them to lose all of their fishing equipment. They had to dump their heavy catch when the vessel became impossible to maneuver.

Fortunately, Alvarenga had managed to transmit a distress signal to the boat’s owner before going radio silent. Unfortunately, the ensuing search effort turned up nothing and was called off after two days. Alvarenga and Cordoba survived by catching fish and seabirds with their hands. After four months with no sign of rescue, apparently Cordoba gave up. He refused to eat and, after securing a promise from Alvarenga not to eat him, he slipped away and Alvarenga dumped his body over the side. Over the next nine-plus months, Alvarenga spotted several container ships in the distance but was unable to attract their attention. On January 30, 2014, he saw a speck of land on the horizon—it was a remote corner of the Marshall Islands, more than 5,500 miles from where he had started. When Alvarenga drifted close enough, he leaped out of the boat and swam to shore. Two locals encountered him on the beach naked and waving a knife, barely able to stand and screaming in Spanish.

At first, no one believed Alvarenga’s story. It seemed implausible that he could have survived 14 months on the open sea; no one had ever survived more than a year under those conditions. Scurvy should have killed him, or so the thinking went. However, the vitamin C he got from the birds and turtles he ate probably saved him. Various ocean scientists studied Alvarenga’s claims and looked at the meandering mid-Pacific currents. They not only determined that such a trip was plausible, but that he was fortunate to have made it as quickly as he did. Alvarenga later passed a polygraph test, ending any lingering doubts. You may recall seeing Alvarenga on television. For a few news cycles back in those innocent days of 2014, he was the lead story. Later, Alvarenga gave a series of interviews to investigative journalist Jonathan Franklin, who published 438 Days: An Extraordinary True Story of Survival at Sea. Finally, and perhaps predictably, Ezekiel Cordoba’s family then sued him for cannibalism.

There are really important lessons to be learned from each of these remarkable tales of survival. If you’d like to know what they are, ask someone else. Or pick up a copy of Field & Stream or Soldier of Fortune. Not being an outdoorsman myself, I have no idea what they are—with the obvious exception of “If you’re thinking about doing something risky beyond the reach of civilization…don’t.”

Did You Know??

Survival stories generate important information about how humans do without food and water. An individual in good health can last a week without food and water before vital organs completely shut down, assuming physical activity is kept to a minimum. Without food, the body needs about 1.5 liters of water (plus a teaspoon of salt) a day to maintain fluid levels. Unfortunately, we know this from hunger strikes.

My stronger, more adventurous camping cousin, who had to get himself to a hospital following a surprisingly serious fly-fishing injury, would no doubt correct me. He’d say, “Aw, go ahead and do it…just do it with someone else.”

That’s fine, I guess, as long as that someone else isn’t me.