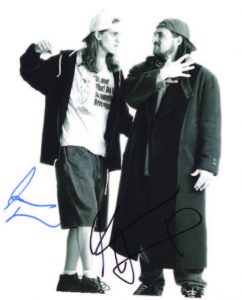

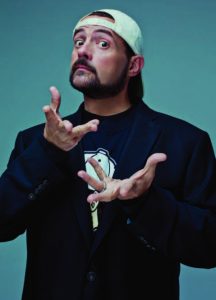

New Jersey’s contributions to American popular culture are historically significant and meticu-lously documented, if not always fully appreciated in real time. Kevin Smith is practically the embodiment of real time. He is in the moment and of the moment, and that has defined his work as a film maker, podcaster and all-around multi-dimensional entertainment visionary. Clerks III, which debuted in September at an historic Jersey Shore movie theater he now owns, is the latest chapter in a three-decade career that has included critically acclaimed films, innovative live tours and podcast mega-success—punctuated by a near-fatal heart attack. The grassroots success of Smith’s first effort, Clerks, taught him valuable lessons about the movie business and the importance of forging a personal connection with his audience. Gerry Strauss asked Kevin to explore the roots of his fascination with film and examine how building connections —with actors, directors and fans—has enabled him to keep moving forward in dynamic, surprising and impactful ways.

EDGE: I admire the passion with which you stay connected with your New Jersey roots. Now that extends to the theater you’ve bought in Atlantic Highlands.

KS: It was one of my hometown theaters where I grew up. We’re coming up with this big mural to put into the lobby that’s got all the people from New Jersey who became successful. Look, there’s Tom Cruise, he was here once, and DeVito and Nicholson and Brittany Murphy. The idea of some kid coming into theater looking up and being like, These people came from New Jersey? Maybe I’ve got a shot—it takes me back to when I was a kid.

EDGE: How so?

Upper Case Editorial

KS: When anybody would reference New Jersey in a movie or TV show, it was like, They know we exist. You felt positively cosmopolitan. You felt like you were part of the conversation. It was thrilling. I think that’s what I’ve always been trying to accomplish, to be part of the conversation. And I found that Jersey is an excellent conversation-starter worldwide. It carries with it credibility that other places don’t necessarily have. If I was from Rhode Island, it wouldn’t make much of a difference.

EDGE: I was thinking about films from my youth with a New Jersey connection, like The Karate Kid, and then realized the first few minutes of that movie they were getting the heck out of New Jersey.

KS: Yes! [laughs] Most Jersey origin stories have people leaving the state. That was one thing I was always proud about. My characters were content to stay within state.

In Clerks II, the plot hinged on whether or not Dante’s going to move away to Florida, and then ultimately he decides to stay. So yeah, New Jersey is in my DNA, man. I absolutely adore the state. It adds this weird layer of working-class credibility—which I think Bruce and Bon Jovi are kind of responsible for—that I have been benefiting from, and it has been absolutely magical. Being from New Jersey has sometimes been the only thing that’s kept my career alive.

EDGE: How do you think storytelling became part of your DNA?

KS: My journey with self-expression, for lack of a better word, began because of a Jersey Girl—specifically, my sister Virginia. I found a composition notebook under her bed when I was about five or six years old. I opened it up and the front page was a drawing of her and her friends kneeling around a cellar door. The title was The Secret of the Cellar Door. “What is this?” I asked. She said, “This is a book that I’m writing. It’s a story about me and my friends on an adventure.” I was like, “You can’t just write a book. You’ve got to ask for permission from the government…we have a library card and Anybody can write whatever they want at any time.” That really captured my imagination. The family had this big electric typewriter, this thing you plugged in and it hummed and it sounded official, and it was very powerful. Once I learned how to use it and tell a story, that electric typewriter became one of my best friends. the flag is on it, and the eagle. It’s official.” She goes, “Look, not every book looks like the books in the library, and you don’t have to get ‘permission’ to write, ever.

EDGE: When did you become conscious of movie making?

Film Venture Intl

KS: There was a movie called Don’t Go into the House that was shot in our neck of the woods, in Atlantic Highlands—including in front of that movie theater that I’m buying. It was a horror movie and the house that represented the killer’s lair—where he would bring women and chain them up and then use a flame thrower on them—is now the Historical Society of Atlantic Highlands. When we were kids, you would watch that movie and you’d be like, that’s here. I could bike to that house. That’s real, that exists. Little tangible moments like that.

EDGE: Nothing locally in the way of influences or role models?

KS: No. The role model had to come from outside of the state: Richard Linklater. When I saw Slacker I was like, Wait, you could be in nowhere, Texas, and make a movie? I didn’t know it was Austin [laughs]. I didn’t realize Austin was the capital of Texas. But a little ignorance went a long way because, when I saw the movie, I was like, This guy making a movie in Texas means that I can make a movie in New Jersey. It was saying that you ain’t got to be from New York or Los Angeles—make it up in your world. He made Austin the backdrop of the city, almost the main character. I was like, where I live is interesting and I’ve got that whole convenience store. So he inspired me more than anybody.

EDGE: Do you take pride in the fact that you’re now serving that role, inspiring up-and-comers?

KS: I love that. Money was never the big driver for me. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not a communist, I’m a capitalist as much as the next guy, but it has never really been the motivator. The motivator at first was for people to hear my voice, my stories, my opinions. Now the driver is the people that you inspire along the way. Richard Linklater did it for me. He wasn’t looking for me. He wasn’t thinking about me. But his art made me believe that maybe I could do something. The same with Spike Lee. I recently saw Spike Lee in Minneapolis at VeeCon, the big NFT convention. We share mutual friends. I told him, “When you started your journey, when you made She’s Gotta Have It, and even before that when you went to NYU, I know you weren’t trying to reach me. But you did and I can’t thank you enough, it launched my ship.”

EDGE: How did he respond?

Miramax

KS: He said, “The professor teaches all students, Kevin. So if I reached you, then that was the point. Then I did my job.” Later he said, “We’re still here. We’re still doing it.” That “we” meant the world to me. That made me feel like such a professional. Seeing Spike take off with She’s Gotta Have It, that was fuel for me later on. It’s no coincidence that She’s Gotta Have It was a black-and-white movie and so was Clerks.

EDGE: It strikes me that the Clerks franchise is the thing you go back to when you’ve got something to say from the heart. Are these movies most personal work among all of the films you’ve done?

KS: I would say of everything I’ve done, the Clerks movies always strike closest to home. Chasing Amy runs second. There’s personal stuff in all the movies, but Clerks started me on this path.

EDGE: You told that story in the first movie so naturally.

KS: It was easy to tell the story because I was in that world. I worked at that convenience store. I was a guy who tended register, man, at a bunch of different convenience stores. So I knew retail and I knew what it was like to deal with customers. When we made Clerks II, twelve years after the first one, at that point I had a full-blown movie career. I didn’t know about retail anymore, so it had to be infused with something else altogether, because it lacked that personal edge of knowing what it’s like to be an employee. The boys had to go on a journey that was kind of similar to mine, where, by the end of the movie they realized, Oh my god…we can be our own bosses instead of just working for somebody else. But Clerks III is super personal because not only does Randal have my heart attack, but then the boys go on and make my movie. They get to make their version of Clerks. That’s been the formula for Clerks since the beginning: take my personal life and fictionalize it to some degree. Clerks III was like midlife crisis fantasy camp. I got to go back to the job that I have a very complex relationship with. When I worked at Quick Stop, I didn’t want to work at Quick Stop. I wanted to be any place else—until 10:30, when we locked the doors and I would hang out inside Quick Stop ’til three, four in the morning with my friends. It was a clubhouse. I loved the place…I just didn’t like working. So I got to go back to Quick Stop all summer when we were shooting the movie, but in the best way possible. I would literally walk in and out of the store and walk in RST Video like I used to in the late ’80s and early ’90s. But I didn’t have to wait on customers and I didn’t have to be there. I was there by choice. And when we were done making pretend that we were working, we all left, walked away. I didn’t have to mop the floors like I used to back in the day. It was the best possible version of working at Quick Stop.

EDGE: You’ve worked with a number of different actors who were just arriving in the film world—Ben Affleck and Jason Lee come to mind—whom you helped shepherd into becoming the stars they became. Do you look back at those times with pride, knowing that you were able to be a part of that development?

Smodcast Pictures

KS: There was a time where I was the big story, so I was able to help Ben and Jason and others. Now I’ll never be as big a story as Ben. So it actually helps me that I was like, “Here, man, let me jump in and let me try to get your movie made” because I had juice back then. The older you are and the longer one stays in the business, the less they give a crap about you…but…because I have people on my side who I’ve been working with since the beginning, since I believed in them before they were famous, I’m able to whip out some cool people to put in a flick. It makes you look hip to some degree. It makes people think, Oh, if that person will still work with them, I guess he’s still relevant. But for me, it’s just like, these are cats that I believed in dearly. And when they get famous you’re like, I knew it! I knew I was right! They’re special and you feel special and smart because you got to identify that quality before anybody else. It’s a sense of authorship. I think of people like Brian O’Halloran and Jeff Anderson who played Dante and Randal in the Clerks movies, Ben Affleck and Jason Lee who played Holden and Banky in Chasing Amy, or Ben and Matt Damon who played Bartleby and Loki in Dogma. Those actors will inhabit those performances for the rest of my life; they are the co-architects of my entire world. Also, it’s nice that they got famous because it certainly makes it easier for me to convince people to let them be in my movies.

EDGE: Initially there was resistance?

KS: In the beginning, I would have to drop the budget to get them into my movie. Chasing Amy was meant to be a $3 million movie. They wouldn’t let me make it for three million with Ben and Joey and Jason, so I dropped it to 250 grand, and then they were like, “Go ahead…now you can make it with your friends.” I hate to make it seem like war—because making art is not like war at all—but I was in the trenches with these kids, making my dreams come true. They were laying the track with me, so forever they maintain in an incredibly special place in my life. So I’ll always reach out to them to try to bring them back into whatever I’m doing. But even if I never worked with them again, the sense of pride I feel when I watch them kind of ascend. It is breathtaking. It’s fun. Ladies and gentlemen, meet these cats that I find really interesting. They’ve become part of the establishment now, part of the business. It’s really cool.

EDGE: Do you think much about your legacy?

KS: I do. The older one gets, the more it’s like, look, it’s paid all my bills and I’ve been happy for the last 30 years, but has anything I’ve done made an impact, or is it just going to go with me when I drop dead. Did I make my mark? You didn’t think about it when you’re making your mark because you’re just focused on doing it. I think I’ve done enough things where it’s like, Oh yeah, they’re going to know you were here. Never mind the actors we’ve worked with who have gone on to be huge movie stars, or dopey stuff like me and Mewes getting our handprints in the cement at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. Love or hate my movies, you can’t deny that they happened, you can’t deny that we were a part of [the culture]. So that makes me happy, knowing that for a few minutes after I drop dead, my work may go on without me. I mean, there seems to be no expiration date on Clerks.

EDGE: Does that surprise you?

KS: It still blows my mind to this day.

EDGE: Have you ever fallen out of love with movie-making?

Allan Amato

KS: Between Red State and Tusk, I took three years off. While I was promoting Red State in 2014, I kept saying, “I’m retiring. This is it. I’m doing a Soderbergh, man. I’m retiring.” Rolling Stone did a big article on it and my mother called me up crying. I had reached a point where I was really disenchanted by how much it costs to release a movie. I knew how to control the cost of making a movie. I made Clerks…I know how to get it real cheap. But you could make the movie as cheap as possible and then you hand it over and they pour $20 million in marketing all over it. That’s how movies don’t get made! I was like, “I don’t have that kind of audience. You don’t need to spend that.” I was so tired of them talking about how We’re going for the widest possible audience. I’m like, “Why? I’m an acquired taste.” If I could admit that, why couldn’t they? I’m not ever going to make a blockbuster, man. I’m an indie film maker. I make Kevin Smith movies and there’s a ceiling to that. Finally, I was like, I don’t want to do this. I’m going to take the movie out on the road myself and not spend any money on marketing. Let’s see if that’s possible. And that was the root of what we do now, the root of the Jay and Silent Bob Reboot Road Show Tour and also the Clerks III Convenience Tour that we’ve got coming up. Anyway, during those three years off I did a ton of podcasting.

EDGE: And how did the podcasting feed into what’s happening now?

KS: I had been touring by myself for years at that point, just standing on stage and talking. But then I started going out there with my friends and these podcasts that I’d been working on. That was where I built the live-show business that I have with my friends. When we go on tour, it’s a blissful experience. People pay $100 to “watch a movie with Kevin Smith.” I am both the celebrant and the celebrated at the same time—I get to connect with the audience. I found something that works for me that makes me happy. During that three-year gap of me not making movies, I had to rebuild my business and all I did was devote myself to podcasting and live shows, which were very successful. And eventually, podcasting led back to film.

EDGE: To Tusk?

KS: Right. Scott Mosier and I were doing episode 259 of SModcast, which was called “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” telling this ludicrous story that we’d read online about a guy who was offering you a room for rent in his house. You’d pay nothing, but for two hours a day you had to dress up in a very realistic walrus costume. So we [brainstormed] this movie just fooling around, going back and forth, and I was like, You know what? That ain’t a joke. That’s a legit movie. So the thing that brought me back to movies was the desire to see a thing that nobody was ever going to do. On the podcast I asked, “Where are all the brave filmmakers who would make this man-to-walrus transformation? Where are the guts?” And then I realized, you used to be a gutsy filmmaker. Why don’t you do it? That’s why, spiritually, I consider Tusk to be the “sequel” to Clerks. Clerks was a movie that was made without thinking about critics, not thinking about box office, not thinking about film festivals—I didn’t even know about film festivals. I just wanted to see the movie. Tusk brought me back into movies and that passion has stayed reignited ever since.

EDGE: Did the heart attack you suffered four-plus years ago help reignite your passion, too?

KS: It sure upped the ante. When you almost die, suddenly you’re like I’ve still got a bunch of things I want to do. I just wasn’t done talking yet.

Editor’s Note: The Atlantic Moviehouse had its gala opening in September. For photos from that event and more on Kevin Smith’s plans to use the space as a multimedia venue, go to edgemagonline.com and click on his Q&A.