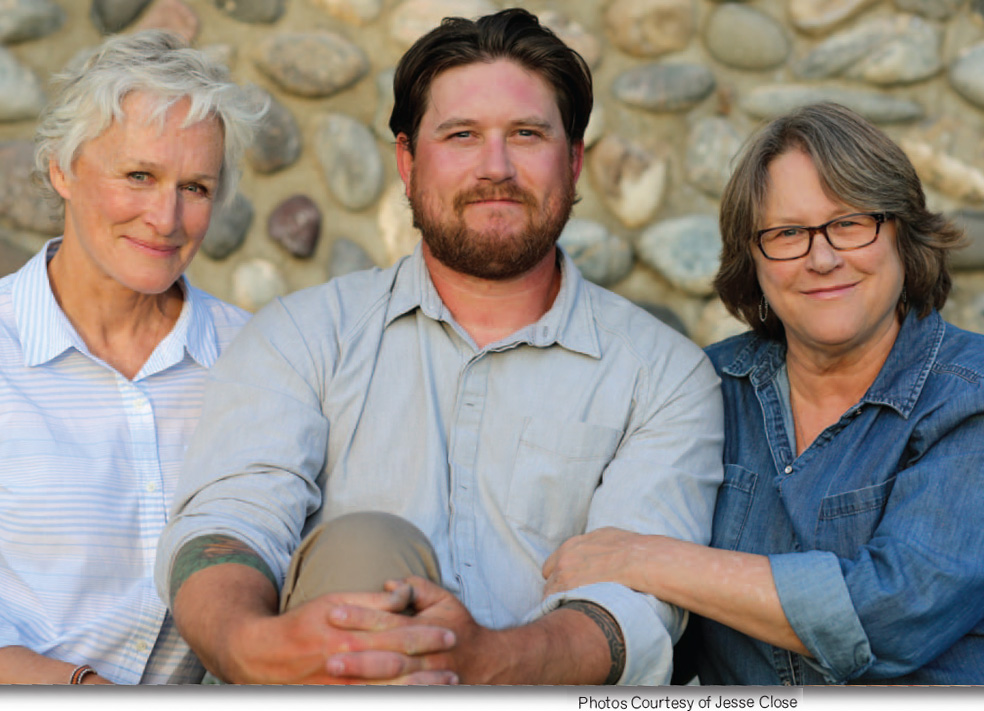

On October 26th, mental health advocate Jesse Close and journalist Jack Ford will discuss the importance of “Easing the Behavioral Health Stigma” at the Trinitas Health Foundation’s virtual Peace of Mind Event, with proceeds helping Trinitas expand its inpatient unit for adults dually diagnosed with intellectual/developmental disabilities and severe mental illness—New Jersey’s only inpatient facility that cares for these patients. Close, the younger sister of actress Glenn Close, is a writer, photographer and mental health advocate whose own battle with bipolar disorder illustrates the critical need for early diagnosis and treatment. She speaks with great passion and humor on a subject with which she is intimately familiar.

EDGE: Something that friends and family and co-workers have come to understand about people struggling with bipolar disorder is that it manifests a little differently for each individual, and also what works as a treatment now may not work as well a week or a month or a year from now. Has that been your experience?

www.istockphoto.com

Jessie Close: Yes. Just recently, in fact, I have started getting off Lithium and onto another drug. It’s going to take a while. I’m still on my full dose of Lithium so I’m not sure how my psychiatrist is going to pull this off. I didn’t realize that Lithium can be quite dangerous if you “cold turkey” it. Luckily, I’m not doing that.

EDGE: You were diagnosed at 50, having gone more than two decades undiagnosed. How did that continue for so long?

JC: I remember as a teenager being sent to live with my older sister, Tina, while I was on a trip with my parents to Africa—I didn’t do well over there—I said to her, “I’d really like to talk to a psychiatrist.” She said, “Oh, we don’t do that in our family.”

EDGE: Was that a New England thing?

JC: Yeah, yeah. Stiff upper lip, you know. However, I knew there was something wrong. I was born in 1953 and the stories I’ve heard from that era are about people having lobotomies. We weren’t respected as people. We were “crazies.” I’m so happy that so many young people are now getting help sooner than later. Bipolar disorder can hit young men from around 17 years old up, while for women it usually hits us in our 20s, sometimes earlier. I don’t know why that is.

EDGE: Do you think the healthcare system in this country, as currently constructed, is adequately equipped to deal with mental illness?

JC: I would hope so. But we’ve had a running battle for years with our hospital here in Bozeman, Montana, trying to get them to create a mental health unit, and they’re just fighting it and fighting it. If you have Apple TV, you can watch a show Glenn and I did called The Me You Can’t See. It’s done really well. There is a sequence in that show where the hospital rep says, “We want it to be perfect.” My sister pipes up and asks, “How can it be perfect if you haven’t even started?”

EDGE: During the COVID-19 shutdown, a lot of the people who might have noticed someone with a bipolar disorder going off the rails no longer had regular face-to-face contact, where they could check in or intervene. Is that one of the under-told stories of the pandemic?

JC: I think the pandemic has caused a lot more mental illness. I was fortunate that Glenn lives nextdoor so we had each other, and my daughter and older son, Calen, were here. But back in March 2020, when we started to isolate, I found it very difficult to just be in my home.

EDGE: Calen is schizophrenic.

JC: Yes. My eldest son, Calen, was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 18. He went off the rails at 17 and we didn’t know what was happening. We went to McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts and met with the Director of the Psychology Research Lab, Dr. Deborah Levy, who unfortunately has since passed away. She studied our family for four years, took blood and tissue samples, and ran the data through her colleagues at McLean. She was able to show how genetic mental illness really is. She described my mother as a “mosaic” because she had three children without mental illness and then she passed it to me. I had three children and passed it on to Calen in the form of schizophrenia. He went to McLean for two years. He was 19 when he went and 21 when he came home and early intervention helped him enormously. He’s an artist and writer now and he takes his meds—you would never suspect that he has schizophrenia.

EDGE: What event precipitated your finally seeking treatment?

JC: It was after a family gathering in Wyoming, where my parents had a house, and I was about to drive with my daughter back up to Montana and I knew I had to say something. I went to Glenn and said, “I cannot stop thinking about killing myself. It’s this constant, monstrous thing saying kill yourself kill yourself kill yourself.” A week later I was at Belmont.

EDGE: Had you had the benefit of an early intervention, how do you think that would have changed things?

JC: Well, I wouldn’t have had five husbands [laughs] that’s for sure! When I speak at events like Peace of Mind, I ask, “Who in this audience has been married five times?” So far no one has raised their hand.

EDGE: My mother was married five times…but I suspect it was because she was a narcissist. Anyway, going forward now, even if no one raises their hand, at least you can say you know someone!

JC: [laughs] Well, I so wish I had been diagnosed earlier because I know I wouldn’t have had five husbands. I was out of my mind most of the time. I haven’t been with a man since 2004 and I’m very happy about that. I’ve gotten so much done. I’ve had shows with my drawings, I’m getting ready to send a new novel to my agent, I have two photography projects going and I can help with my three grandchildren. I attribute all of that to being on the right medication. But, yeah, I do have very deep regret that I wasn’t diagnosed sooner. I’m pushing 70 for God’s sake.

EDGE: For individuals with a bipolar diagnosis, a common trigger is seeing their siblings have success or just having a good time. Was this something you experienced as Glenn’s entertainment career unfolded?

JC: It wasn’t much of a factor in my case. I saw how hard she works. She has to travel, remember lines—it’s a brutal career. She has done so well because she works her butt off. Glenn is six years older than me and has always been my big sister. I remember like it was yesterday how she would take me up to her room, where she had a blackboard. She taught me how to do the letter “i” and I loved the dot then and I love it now. She was very good to me and continues to be.

www.istockphoto.com

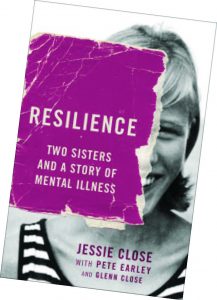

EDGE: You wrote a book entitled Resilience. How do you define that word?

JC: I was resilient because I didn’t commit suicide. I’ve had three attempts; thank goodness they were all thwarted. There is a scene in the book when I was married to my last husband when we were living way out in the boonies in Montana. I’d made a mental note he’d left his handgun on the seat of his truck—he usually kept it locked up. I got drunk and went out and was about to open the door and thought to myself, All three of my children will hear the gun go off and come outside and see me. I just couldn’t do that to them. So my kids “saved” me. Later, in 2004, after that husband fled, I finally went to the hospital and got help. That’s when they started me on Lithium.

EDGE: Beyond getting the right medication, how did that experience change you?

JC: Being around other people with mental illness was so wonderful, because you all speak the same language. It was amazing.

EDGE: When you appear at events like Peace of Mind, what do you want the take-away to be for the audience?

JC: I want to open their eyes to the fact that those of us who are mentally ill are human. We have the same feelings as everybody else…they might just get exaggerated. I want them to laugh, I want them to realize in their gut that, if you treat people with mental illness with love and kindness—and understand that they can get help—that it’s quite amazing how medication gives our brains what they need and turns us around. And if there is someone in the audience who is concerned about a family member, I hope after listening to me they will do something about it. EDGE

Editor’s Note: For more information on Peace of Mind, visit trinitaspeace.givesmart.com. For tickets, call (908) 994–8249. Trinitas operates one of the most highly respected and comprehensive departments of Behavioral Health & Psychiatry in New Jersey. Services are offered along a full continuum of care, with specialized services available for adults, children, adolescents and their families, as well as services for those with various substance use disorders. In addition to operating a 98-bed inpatient facility, the medical center provides almost 200,000 outpatient behavioral health visits annually.