More than one historian has observed that New Jersey has a legitimate claim to being the golden cradle of American popular culture. A decade before the first cameras rolled in Hollywood, Fort Lee was the birthplace of the motion picture industry. A half-century before Las Vegas, Atlantic City was America’s first playground. Red Bank produced Count Basie, Hoboken Frank Sinatra. In 1926, the Patron Saint of Comedy, Jerry Lewis, entered the world in Newark and later announced his arrival with the immortal words Hey Laaaaady! This fall, the 90-year-old Lewis starred in the title role of Max Rose, portraying an octogenarian pianist dealing with the loss of his beloved wife. Filmmakers Luke Sacher and Carole Langer have known Lewis and his family for decades. They asked him to peel back the veneer on his 70-plus years in show business and talk about the Jerry that his fans rarely get to see.

Soapbox Productions

EDGE: When you and Dean Martin began working together at the 500 Club in Atlantic City, were you looking for a partner?

JL: No, it was an accident. I wasn’t looking for anything. The singer got laryngitis, and [club owner] Skinny D’Amato said to me, “Do you know anybody?” After the first night he was on the stage with me, I knew we had lightning in a bottle. He was just hoping to get through the two weeks so he could pay a car payment. When I took Dean for a tux after two weeks, he said, “What the hell do we need tuxes for?” I said, “Because, before the end of a year, we’re going to be making around five thousand bucks a week.” He said, “You’re crazy! You’re nuts. We’re going to go and spend three hundred a piece for tuxedos?” I said, “Trust me. Let’s just do it. We’re going to have to look like what they’re spending.” And in less than six months, we were getting five thousand a week.

Soapbox Productions

I was writing immediately, the minute I got him in Atlantic City. But listen…he was a klutz. Dean moved on the stage like he had three pounds of [poop] in his pants! He was the klutz of the world! After we were together a couple of years, he started to take on a little bit of ambiance, and movement and grace, because we were learning, and we were honing our profession, our craft.

If he didn’t have to put his mind to work, he didn’t. Yep. He could take a nap fifteen minutes before opening night at the London Palladium with Her Majesty the Queen in the audience. We always knew that, the way we had it—I handled the business, I did the editing, I did the writing—it worked.

He played golf. But, it’s very important to say for Dean that when he came from the golf course, and I finished writing the material, and we would put it on its feet, he knew it in five minutes. And [his timing] was impeccable. It could be on take one, he had it so well. What [people] didn’t understand was that they couldn’t have seen me if he wasn’t there. He was the spine of the whole act. I did tell him the following: “You can’t take a pratfall in a grey suit. It doesn’t work.” He said, “Why?” I said, “’Cause you can go down to the Bowery and see fifty, sixty grey suits laying in the gutter. But when you take a fall on a dusty floor, wearing a three thousand dollar tux. That’s funny.”

Dean was my hero, my big brother. My confidant. And one thing I knew best about him was that he hated pathos. Because it would dig in and find something that he was working so hard and so desperately to keep behind the facade. Let me tell you how he was brought up. He was brought up by an old Italian family, who gave him a couple of prerequisites: 1) grown men don’t cry and 2) you never take money out of your pocket, you just put it in. You share with no one. And 3) there is no one on earth that cares about you. You, therefore, have no reason to care about anyone else. That was his training. And they did a good job. The only man that ever got through to Dean was me, because of my passion, because of how much I loved him.

EDGE: Besides raising money for causes like muscular dystrophy, you have used your stature in the business time and again to stand up for friends and co-workers.

JL: I’ve never used fame or power for myself. With the exception of underdogs, of course, or people that are maligned or demeaned and have no recourse. I love to get on my white charger…I had it as a kid, in grammar school. If I saw somebody that was being unjustifiably treated, I had to do something about it. I didn’t see anyone else doing anything about it, I always had to. I had a Holden Caulfield kind of a gut that drove me to do the things that I did. And I find that in my older years, as I look back, I feel tremendous self-esteem for what I did. Talking about them sometimes diminishes them; I’m not often comfortable talking about the nice things that you do. I’m not sure if it’s a selfless act—I have a feeling it’s a selfish one. Because I get so much pleasure out of seeing that they’re not demeaned anymore.

I’ve always had a fair doctrine that runs through my blood. If I see a producer bump into my camera operator, or my sound man, or my grips or my electricians—and doesn’t even know their names—I’m going to teach him a lesson in manners. I’m very protective of the people I work with. Because I know that they are the unsung heroes of everything I’ve done.

I remember a time, in the early 1960s, Paramount brought an efficiency expert out to Los Angeles. He thought it would be a good idea to get rid of the watchman on the West Gate at Paramount Studios. Now, I grew up with this watchman. From the time I came to that studio, Jess was my friend. They dismissed him, after 42 years. It was a bean pusher who picked the name out of a hat, and that was that. So I called Joe Stabile [my executive producer]. I said, “Get a Mayflower moving van and have it parked outside my office. We’re out of here!” The Mayflower van got there, and it was a humongous 18-wheeler. Y. Frank Freeman, the Chairman of the Board of Paramount West Coast, could see it from his office. I went into Y. Frank Freeman’s office, and said, “You see that truck, Frank? That’s going to have all of my office and all of my staff. We’re going to load it in, and drive off this lot, if Jess doesn’t get his job back.”

He looked at me and he said, “Well, I don’t really understand. You bring this company 800 million dollars in film rentals. Isn’t that a larger issue than one man?”

I said, “You’re not listening to me. If you can’t put the price on one man’s life, 800 million doesn’t mean a thing. And you didn’t know it was happening, Frank. An ‘efficiency expert’ has done this, and I’m expecting you to fix it so that I can pay this guy that drove this Mayflower truck—pay him a nice little gratuity—and have the truck depart from the studio.”

EDGE: You also stood up for Sammy Davis Jr. in Las Vegas when he was performing with the Step Brothers.

JL: Absolutely. Vegas in the ’50s was still pretty much like the Deep South. One night after a performance, I saw Sammy in the dressing room—having dinner! And in the next dressing room were the Step Brothers having dinner. I said, “What the hell is going on here?” He said, “We’re not allowed in the Garden Room.”

So I went to a couple of my friends who ran the hotel and I said, “I don’t think you’ve got a show at midnight—and it’s a Saturday—unless you start adjusting some of your rules. The Step Brothers will eat in the Garden Room, and go anywhere they want in the hotel. Or I’ll do one of two things: not appear, and/or have a press conference. And let the rest of the world know that you’re building this empire on the kind of stuff that we’re trying to get out of this country. It was fixed.

Soapbox Productions

Sammy and I were friends for 45 years. We had a Damon and Pythias friendship, closer than any man and wife, closer than any two friends could ever be. The reason we were that way was because we didn’t take ourselves too seriously. We made jokes about the stupidity of ignorance, and the stupidity of racism. We had the best time laughing at all of that crap! I said to him, when he converted to Judaism, “You didn’t have enough trouble being black?Jesus Christ, I mean, you got a death wish? You’re black and you want to be a Jew also?” I said, “All we have to do is have a car accident, and you’d lose one eye!” And sure enough…

I was there the night of the accident. It was a very straightforward accident. He was driving straight, and a car hit him head-on. No reason, no nothing. He was on his way to Los Angeles, felt like driving, to relax, and he was hit by an oncoming car. He was lucky to be alive, but he lost his eye. I sent him watermelon and Kentucky Fried Chicken in the hospital, so he’d be comfortable. And Matzo!

EDGE: When did you first meet Sammy?

JL: Let me see, the year had to be 1950, Ciro’s Night Club, Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles. I went to see [him with] the Will Mastin Trio, and I knew I was experiencing lightning in a bottle. His presence on the stage felt like there were fans that were pushing you into the back of your seat. I hadn’t had a feeling like that since I saw Jolson when I was five years old. At the end of the show, I went backstage to see him. He was young, it was the first big shot for them, and I had some notes for him. And I’ll never forget his first remark. He said, “We haven’t met yet and you’re monitoring me?”

I said, “You’re doing some things on that stage that border on genius, and then you turn around, and you do some things on that stage that border on amateur. So I thought I would mention it to you. ’Cause you don’t need the latter.” One of the notes that I gave him that first night was you can’t walk out looking like a bookie at a racetrack. Which is what he looked like. I also gave him a couple of ideas about transposing material. He did some wonderfully strong things too early, and couldn’t rise above them—though he stopped the show cold. It was an incredible performance.

EDGE: Who did you learn the most from during your career?

JL: My father. My father taught me everything…I’m just still trying to get it right. He was the most brilliant performer that ever lived. He did the mime better than I did, he conducted better than I did, he was funnier than I ever was, he sang better than I ever sang, he danced better, he had an Astaire kind of quality. The women absolutely went nuts when he would sing a love song, and in a heartbeat he’d have his stupid hat on, doing crazy walks that I learned from him. I learned everything from my dad.

He was right about a lot of things. He was right about, when you walk out on the stage, and that lady paid $70 to see you, you have only one responsibility, and that’s to work your [rear end] off. And if you’re going to be a consummate professional, he said, sweat. “I’ll be embarrassed and offended if you ever walk off that stage dry. That means you dogged it, you didn’t give 100 percent, and you’re getting careless.” He got me to where I am. Let’s put it this way. I once told somebody, most men in this world don’t mind being one of the two hundred drummers in the parade. I do mind. I had to carry the baton. You want the baton? It carries a lot of responsibility.

So it was my dad’s birthday, and I called General Motors.

Soapbox Productions

A.L. Roach was Chairman of the Board of General Motors, and I said, “My dad’s never driven a car in his life, and he’s going to be 50 years old. I want to get him a Patton Tank, so that if he gets into an accident, at least he’s surrounded by better than what they’re making today.” And I paid$100,000 to have that four-door sedan made. And in 1957 or ’58, that was a lot of money. They built it for me, F.O.B. Detroit, delivered to me in Los Angeles. I put red ribbons around it, I drove it to his house. I went up to the door, rang the bell. I said, “Happy Birthday, Dad, look!” and he said… “It’s not a convertible.”

So I was shattered for a moment or two. Then I went on to explain the reason that it’s a four-door sedan is that you’ve got much more protection. “It was built to protect you and mom.” But I never forgot he said that. He just wasn’t thinking, that’s all. He didn’t mean to hurt me. I was so full of myself then, driving so hard to reach those galaxies I dreamed about. I was very vulnerable.

The love, when it’s right, that the father has for the child—only God can explain to us the dimension of that love. And I knew that I had that from him. And I also knew that he had it for me. But when I was quitting school, he was very clear: “If you’re not going to complete your high school education and not be able to go on to college, there’s a Band-Aid that can be put on this decision you’re making. And that Band-Aid is, go out in the world, and ask everybody anything you want to know. You’ll become articulate, in some cases prolific. You’ll be bright. You’ll get an education better than anything they’d ever give you at Dartmouth—if you’ll do that. I need you to attempt that, because without a formal education, you will get shot down at some time, and not be able to recover.”

Hopper Stone/Falco Ink

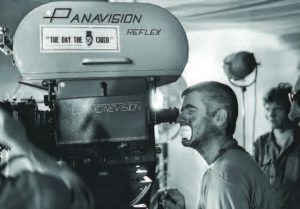

JERRY ON THE MAKING OF MAX ROSE…

The last time I read a script I thought would make a wonderful movie was The Nutty Professor. I haven’t had the experience of film making for 20 years, but you don’t forget it, you remember every frame. I fell in love with this script on the first read, which is incredibly different than normal. I’ve read scripts 15 times and couldn’t get them to work.

What attracted me to [Max Rose] was how love can really generate a difference in the personality of a human being. I fell in love with the thought that anyone can fall in love, and that everyone will fall in love. And the beauty of love, as far as I’m concerned, is that it makes you better—it makes you stronger, it gives you direction and gives you an understanding of what life is and what we’ve been given.

We had fun but we had to concentrate. It’s the only film I’ve ever made that kept me absolutely dedicated—without any adjustments or additions. Just do the script—the script is honest, it was written well. There was nothing I could do, other than spoil it, other than to do the scripted material.

AT THE COPA, COPA CABANA…

In April 1948, Dean and Jerry were booked into New York City’s Copacabana—arguably the most prestigious nightclub in America—as the supporting act for movie star and songstress Vivian Blaine. Blaine would be cast as Adelaide in the original Broadway production of Guys and Dolls two years later. The Copa was owned and managed by Jules Podell, whose connections to the mob were common knowledge.

Sonny King, one of the great lounge singers of that era, once explained to me: “Look, they owned all the clubs and showrooms all over the country, right? New York, Philly, Atlantic City, Chicago, Hollywood, Vegas. So who are you gonna work for? The guy who owns the delicatessen?”

Anyway, on opening night, the crowd went wild for Dean and Jerry, and simply wouldn’t let them off the stage. Vivian Blaine was forced to come on late and shorten her act. At the end of the show, Podell told Blaine that she would now be opening for Martin and Lewis—not only the following night, but for the rest of her booking. She quit.

One night later that week, between the early and late shows, Dean was chatting with maître d’, Joe Lopez, while Jerry was working the bar with his “whacko” routine. Suddenly, a very well-dressed older man with a serious face shouted at Lewis Why don’t you knock it off and shut up!

Jerry stayed in character, pointed at the man, and retorted just as loudly, “See, folks? That’s what happens when cousins get married.”

The man rose from his chair, approached Lewis, and informed him that if he opened his mouth one more time, he would be collecting his own teeth from the floor. Jerry took just long enough to respond for Dean to rush over and apologize for his younger partner’s rudeness. Sensing he had crossed a line, Jerry apologized, too.

Keep your partner away from me, the man warned Dean, as he escorted Jerry away.

“You tell him he’s lucky I got a sense of humor!”

“You tell him he’s lucky I got a sense of humor!”

Dean informed Jerry moments later that they had just apologized to Albert Anastasia (right), known less for his sense of humor than for his status as lord high executioner of Murder Incorporated.

Editor’s Note: The stories in this feature were recounted by Jerry to Carole Langer during the making of an A&E documentary. His thoughts on Max Rose followed a later screening of the film in Las Vegas. Carole was nominated for a Primetime Emmy for her Biography episode on Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack, and received the DuPont Silver Baton for “Who Killed Adam Mann?” on PBS Frontline. Luke Sacher—an Emmy-nominated videographer, writer and editor who shot and edited both programs—has been a friend to (and fan of) some of the true legends of the entertainment world. Janet Leigh was like an aunt to him, he recalls. “She was one of the best women that ever lived. My grandfather, actor/director Abner Biberman, was Tony Curtis’s first drama coach. Both Tony and Janet were best friends with Jerry Lewis. Tony once told me that Frank Sinatra was ‘the teacher of all of us.’ But I’ve always felt, personally, that Jerry was my most important teacher as a child. His movies were more than just silly fun to me…they were moral lessons that helped mold my sense of right and wrong, and championed the power of love and kindness and empathy to make life worth living. No fooling.”