There is simply no explaining some of history’s weirdest trends.

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Until the imitators suddenly realize how stupid they are. Our cultural history is littered with absurd trends that enjoyed a shining moment of mass fascination, only to wind up as objects of ridicule. Most have been mercifully laid to rest for all time, yet others inexplicably continue to rise from the crypt, rediscovered or reinvented by a new generation. The following trends have yet to return—thankfully, but perhaps not permanently. Just remember, as you read about them and chuckle, there is no telling what can happen when a few million of us decide together that some thing is the next big thing.

Color Me Dreadful

The 1970s may be remembered for outlandish fashion and funky, eye-popping design, but that is more a product of retro TV commercials and revisionist history than reality. Clothing, carpeting, drapes, furniture, countertops, cabinets, appliances and even cars were drenched in drab, dreadful burnt oranges, dark walnuts and two of the ugliest colors ever yet realized: Avocado Green and Harvest Gold.

Those who claim there is “no accounting for taste“ might be surprised that a good deal of accountability for these nauseating hues lies right here in New Jersey. For more than a half-century, a select committee of 10 people, whose identities have never been disclosed to the public, has met twice a year with executives of Pantone, a company based in the Bergen County town of Carlstadt. Founded in 1963 by Lawrence Herbert—who created a system for identifying, matching, and communicating colors for consistency across all design industries—Pantone has a mind-numbing 1,925 colors in its current catalog. Its Color Institute studies how “color influences human thought processes, emotions and physical reactions, furthering its commitment to providing professionals with a greater understanding of color and to help them utilize color more effectively.” Avocado and Harvest were Pantone creations; their sister colors included Navajo White and Selective Yellow, which sound vaguely racist today.

I was a pre-teen in the early ’70s, and I swear that almost everything that came in more than one color also came in Avocado Green and Harvest Gold. My objection to these colors is perhaps more visceral than it ought to be. One weekend in 1972, my parents rented an enormous Avocado Green Plymouth Fury station wagon (with matching interior) while waiting for our little white Audi wagon to be repaired for the umpteenth time. Halfway through the 100-mile journey to our summer house in the Catskills, the noxious smell of the Naugahyde, combined with the nauseating color scheme, literally made me vomit. It was the last time that I remember ever being carsick. Now you won’t find a single Avocado Green object in my home. Well, except for actual avocados, which I love. Go figure.

I was a pre-teen in the early ’70s, and I swear that almost everything that came in more than one color also came in Avocado Green and Harvest Gold. My objection to these colors is perhaps more visceral than it ought to be. One weekend in 1972, my parents rented an enormous Avocado Green Plymouth Fury station wagon (with matching interior) while waiting for our little white Audi wagon to be repaired for the umpteenth time. Halfway through the 100-mile journey to our summer house in the Catskills, the noxious smell of the Naugahyde, combined with the nauseating color scheme, literally made me vomit. It was the last time that I remember ever being carsick. Now you won’t find a single Avocado Green object in my home. Well, except for actual avocados, which I love. Go figure.

Beanie Weenies

We all grew up with Jack and the Beanstalk, the tale of a boy who trades his family cow for a handful of magic beans. In most versions, Jack comes out on top of this transaction. This was not the case for the countless millions who exchanged fists full of cash for a different type of bean-based promise. This story begins in 1986, when Ty Warner, the top salesman at Dakin & Co.—the world’s largest maker of stuffed toys—suggested to the higher-ups that using plastic “beans” as filler instead of stiff cotton would make the toys more flexible and posable. He was thanked by being fired.

Warner pressed on with his idea and, in 1993, founded Ty Inc. to produce Beanie Babies. Warner saw the product itself as secondary to the marketing. He priced Beanie Babies at an affordable $5, but sold them only in limited quantities to small specialty shops and toy stores rather than big-box chains—to raise desirability by creating scarcity. Consumers could never find an entire collection of Beanies at one single store.

Warner pressed on with his idea and, in 1993, founded Ty Inc. to produce Beanie Babies. Warner saw the product itself as secondary to the marketing. He priced Beanie Babies at an affordable $5, but sold them only in limited quantities to small specialty shops and toy stores rather than big-box chains—to raise desirability by creating scarcity. Consumers could never find an entire collection of Beanies at one single store.

In 1995, Warner started “retiring” certain Beanie Babies, triggering explosive interest in the secondary collector market. Prices for these originals surged past $20. Meanwhile, Warner’s overseas factories were pumping out boatloads of non-retired ones. By 1998, Ty Inc. was making more than $1 billion in profits.

By the turn of the 20th century, rabid collectors and misguided investors, uninterested in trivialities like supply and demand, had become obsessed with collecting Beanies as an investment. The arrival of eBay around this time only fueled their madness; some of the rarest were selling online for as much as five figures. In 1999, Warner officially “retired” several more Beanie Babies, but this time there wasn’t any market response—no notable increase in value or spike in demand. It was the beginning of the end.

Collectors panicked and flooded eBay with tens of thousands of them and their value blew away like sand in the Sahara. In desperation, Warner ordered all production halted by the end of the year, but his announcement did nothing to stop the big bust. By the early 2000s, most Beanies were worth between 1 and 5 percent of their former prices and wound up in truck-stop claw machines. Don’t be too quick to shed a tear for Warner, however. In 2020, the 76-year-old ranked 359th on the Forbes 400 list of the richest people in America, with a net worth of $2.3 billion.

Record Breakers

Half a century ago, before the internet, cable and even VCRs, the big three national broadcast television networks (CBS, NBC and ABC) produced pretty much all there was to watch. When they struck gold with a hit TV series, they often attempted to leverage their stars’ popularity by ushering them into the recording studio—whether or not they had even a shred of singing talent. Not to worry, they could always cut a spoken record. With very few exceptions, the result was a hilariously awful novelty single or, worse, a full-blown album. And, of course, they sold like hotcakes. These ill-conceived celebrity records are collectible kitsch today, but back in the 1960s they could be found in almost every home in America. These celebrity recordings are a few of my personal favorites. All can be found online:

A 1965 episode of The Addams Family featured Ted Cassidy (aka Lurch) as an overnight teen idol pop star. Cassidy teamed up with Gary Paxton—producer of “Alley-Oop” and “Monster Mash”—on a Motown-style dance single entitled “(Do) The Lurch.” Cassidy actually performed it on the popular variety shows Shivaree! and Shindig! for Halloween.

Sebastian Cabot, who is best remembered today for his role as Brian Keith’s butler, Mr. French, on Family Affair—and as the voice of Bagheera in Disney’s The Jungle Book—recorded a full album of poetic interpretations of Bob Dylan songs in 1967. Sebastian Cabot, Actor featured a full orchestra, and included “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Blowin’ In the Wind” and “It Ain’t Me, Babe.”

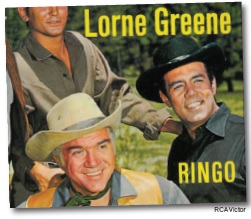

Lorne Greene, who played frontier patriarch Ben Cartwright on Bonanza, had a #1 hit on the US Billboard charts on December 5, 1964 with “Ringo”— a 45 from his album Welcome to the Ponderosa. Singing satirist Allan Sherman re-recorded the song as “The Ballad of Ringo Starr.”

Lorne Greene, who played frontier patriarch Ben Cartwright on Bonanza, had a #1 hit on the US Billboard charts on December 5, 1964 with “Ringo”— a 45 from his album Welcome to the Ponderosa. Singing satirist Allan Sherman re-recorded the song as “The Ballad of Ringo Starr.”

In 1966, when Batman was the top-rated TV show in the US and “Bat-mania” was sweeping the country, MGM Records signed Burt Ward (aka Robin) to release “Boy Wonder, I Love You” and “Teenage Bill of Rights”—written and arranged by none other than Frank Zappa and performed by The Mothers of Invention. “It was one of the weirdest projects I’ve ever been involved in,” Zappa later reflected.

On the subject of weird, among the most famous/ infamous celebrity albums was a 1968 LP entitled The Transformed Man by TV’s Captain Kirk, William Shatner. It included a disturbing version of Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” as well as dramatic readings of Shakespeare. George Clooney once included The Transformed Man in his “desert island disc” collection as an incentive to get off the island. Shatner’s rendition of “Lucy In the Sky with Diamonds” was once voted the all-time worst Beatles cover.

Unsafe at Any Speed

Back in the 1960s and ’70s, nothing was cooler than motorcycles and sportscars. Steve McQueen said so! Naturally, kids wanted bicycles that looked like both. So in 1963—the same year that Chevrolet began using the same name for its Corvette—Schwinn introduced the Sting-Ray (below), touting it as “The Bike with the Sports Car Look.” Schwinn’s R&D director Al Fritz was inspired by middle schoolers in Southern California, who customized their old bikes. The concept was quietly ridiculed by upper management… until the entire first production run of 45,000 sold out in two months.

Fast-forward to 1969, when Easy Rider grossed 60 million dollars worldwide. Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper were nominated for Oscars, but the real star of the movie was Fonda’s “chopper,” which was fitted with Angel Forks that extended the front wheel far forward, with no front brake. Fonda couldn’t turn or stop it, but he sure looked good trying.

My 5-speed Sting-Ray was a dream ride: banana seat, ape-hanger handlebars, a fat rear tire, chrome flared fenders, hand brakes and a “Stik-Shift” mounted to the top frame bar. After Easy Rider, I was one of the countless kids who added Angel Forks to their Sting-Rays. The challenge was learning how to keep from jack-knifing on turns. It took a lot of nasty falls on unforgiving blacktop before getting the hang of it.

My 5-speed Sting-Ray was a dream ride: banana seat, ape-hanger handlebars, a fat rear tire, chrome flared fenders, hand brakes and a “Stik-Shift” mounted to the top frame bar. After Easy Rider, I was one of the countless kids who added Angel Forks to their Sting-Rays. The challenge was learning how to keep from jack-knifing on turns. It took a lot of nasty falls on unforgiving blacktop before getting the hang of it.

That same year, in Britain, Raleigh launched its competitor to the Sting-Ray: The Chopper. Loaded with many of the same features as its American cousin, it was also designed specifically for popping wheelies. Back heavy and inherently unstable (the front wheel was 20 percent smaller than the rear), it wobbled dangerously at even moderate speeds and was prone to flipping “arse over tea kettle.” As with the Sting-Ray, its solo-polo seat and sissy bar encouraged double riding; its stick shift was nicknamed the “Impale-o-Matic.”

A few years ago I wrote a story for this magazine that reminisced about potentially lethal toys from the 1960s and ’70s. The Chopper didn’t quite make the cut, but it provided some painful lessons in physics for its young owners. Despite an alarming number of near-fatal accidents being reported in the press—and public safety experts decrying the Chopper as “a dangerous toy”—sales jumped 55 percent in two years and remained robust until the 1980s, when the BMX craze arrived, replacing one cool trend with a safer one that included pads, helmets and other sensible items.

Both the Sting-Ray and the Chopper are fondly remembered today by 50- and 60-somethings. Why the nostalgia for all those face-plants and near-castrations? As Hunter S. Thompson wrote of this generation in his book Hell’s Angels, “They shun even the minimum safety measures that most cyclists take for granted. You will never see one wearing a crash helmet. Anything safe, they want no part of.”

Pole Cat

Alas, some trends truly defy reason or explanation. In 1924, a Hollywood theater owner hired merchant sailor, movie stuntman and childhood human fly (how’s that for a résumé!) Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly to perch atop his building’s flagpole, as a publicity gimmick, for 13 hours and 13 minutes. It worked…all too well. Almost instantly, Kelly became a national celebrity and flagpole-sitting became an American obsession. For the rest of the decade, young people were scaling flagpoles hoping to set new records and attract newsreel cameras for a few flickering seconds of fame.

Alas, some trends truly defy reason or explanation. In 1924, a Hollywood theater owner hired merchant sailor, movie stuntman and childhood human fly (how’s that for a résumé!) Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly to perch atop his building’s flagpole, as a publicity gimmick, for 13 hours and 13 minutes. It worked…all too well. Almost instantly, Kelly became a national celebrity and flagpole-sitting became an American obsession. For the rest of the decade, young people were scaling flagpoles hoping to set new records and attract newsreel cameras for a few flickering seconds of fame.

Kelly pursued his new vocation with zeal for the remainder of the Roaring ’20s. He appeared in 28 US cities, continually raising the height of his flagpoles, duration of his performances and, of course, his appearance fees—to a jaw-dropping 100 dollars an hour. His crowning moment came in 1930 here in New Jersey, on Atlantic City’s Steel Pier, when he sat on a 200-foot pole for an incredible 49 days and one hour, which is still a world record.

Daredevil stunts fell out of favor during the Depression, and Kelly soon came to be regarded as a public nuisance. His last hurrah was in 1939, when Dunkin’ Donuts sponsored him to consume its product while doing headstands on a wooden plank outside the 54th floor of the Chanin Building on 42nd Street in New York City. Kelly rejoined the Merchant Marines during World War II. After the war, he became destitute. He collapsed and died in 1952 on a street in Hell’s Kitchen, where he’d grown up as an orphan, holding a diary of his more than 13,000 hours of flagpole sitting. He had titled it The Luckiest Fool on Earth.

Editor’s Note: Luke Sacher is a documentary film maker who has authored several articles for EDGE, including loving looks at mad scientists, catastrophic business decisions and the aforementioned dangerous toys. He also interviewed Jerry Lewis and his son, Anthony, for the magazine. Luke actually does own one of the truly rare Beanie Babies, although it is no longer worth thousands; his mother bought it at a garage sale for less than a dollar.