How much is enough? How much is too much?

By Christine Gibbs

Don’t Bother, Homework Is Pointless. When this headline ran in The New York Times during the 2014–15 school year, you could practically hear the jubilant roar of elementary school students and their parents. Imagine a world without nightly assignments. No more badgering. No more meltdowns. Utopia. The writer cited research that almost universally drew the same conclusion: Homework in the K-thru-8 world is practically pointless.

Three years later, despite mounting evidence that a 20th Century approach to homework does not adequately address the needs and challenges of the 21st, the war between those in favor of homework and those against it rages on. The anti-homework faction has amassed a mountain of newspaper stories like the one in the Times and can also cite serious studies, with statistically significant results, published in countless treatises and on endless websites. For example, research performed at Stanford University found that among 4,300 students in high-achieving California communities, those who spent two hours on homework experienced more stress, physical health problems, lack of balance, and even alienation from society.

Three years later, despite mounting evidence that a 20th Century approach to homework does not adequately address the needs and challenges of the 21st, the war between those in favor of homework and those against it rages on. The anti-homework faction has amassed a mountain of newspaper stories like the one in the Times and can also cite serious studies, with statistically significant results, published in countless treatises and on endless websites. For example, research performed at Stanford University found that among 4,300 students in high-achieving California communities, those who spent two hours on homework experienced more stress, physical health problems, lack of balance, and even alienation from society.

A few daring school districts have been brave enough to implement a no-homework policy in the lower grades, which prompted a visceral reaction from many parents (and even some teachers) who feared it would affect everything from test scores to future college acceptances.

In 2014, sociology professors Keith Robinson and Angel L. Harris authored a book that has become required reading in certain circles entitled The Broken Compass: Parental Involvement with Children’s Education. They present extensive and credible evidence that homework doesn’t help much, if at all. Another conclusion of their research was that parental meddling in homework assignments can actually bring test scores down. This kind of interference, common among today’s helicopter parent population, “could leave children more anxious than enthusiastic about school.” The Race to Nowhere, a 2011 documentary produced by Vicki Abeles—a well-known filmmaker, speaker, and children’s advocate—featured interviews with burned-out students from our own Garden State schools who reveal how too much homework is often detrimental, especially in the early grades. The final conclusion of her film is that “the only homework that actually helps kids learn is reading… just reading.”

So does homework work? Yes, say its proponents. A robust homework regimen has lasting real-world benefits. In her 2011 article, entitled “Why Homework is Good for Kids,” education historian Diane Ravitch pointed out that a little- or no-homework policy is likely to result in students who do not read much, do not write well, or don’t complete assignments. She sums up her defense of homework as follows: “[It] doesn’t help students who don’t do it, but very likely does help students who actually complete their assignments. Duh.”

So does homework work? Yes, say its proponents. A robust homework regimen has lasting real-world benefits. In her 2011 article, entitled “Why Homework is Good for Kids,” education historian Diane Ravitch pointed out that a little- or no-homework policy is likely to result in students who do not read much, do not write well, or don’t complete assignments. She sums up her defense of homework as follows: “[It] doesn’t help students who don’t do it, but very likely does help students who actually complete their assignments. Duh.”

While researchers haggle over the merits of the day-to-day payoff of homework, longtime educators point out facts that are difficult to dispute. Taking homework seriously—i.e. doing it well and doing it neatly (not in the back of the car or wedged into a subway seat)—develops habits for life. One of the great complaints employers have is that a high percentage of their workers do not understand expectations or how to meet expectations, and that accountability seems like a foreign concept. This is true of fast-food workers, Ph.D.’s and everyone in between. Homework helps young people comprehend responsibility and the value of a job well done.

Who makes decisions about homework? Schools typically have a policy on time limits. For younger kids, it’s often a half-hour a night—increasing to 90 minutes or more by middle school, as they have more subjects and become more mature. In most cases, the type and quality of homework is discussed on the division level. The focus is on elevating the students’ cognitive skills.

Who makes decisions about homework? Schools typically have a policy on time limits. For younger kids, it’s often a half-hour a night—increasing to 90 minutes or more by middle school, as they have more subjects and become more mature. In most cases, the type and quality of homework is discussed on the division level. The focus is on elevating the students’ cognitive skills.

Our federal government has long been a proponent of the benefits of homework as part of any good curriculum. Through programs such as No Child Left Behind, countless millions of dollars were aimed at ways to improve education—almost all of which emphasized homework as a valuable teaching tool. Such programs unfortunately fell short of their goals through inefficiency at the state level. As these programs failed, so did the undisputed confidence in the rewards of a hefty homework regimen.

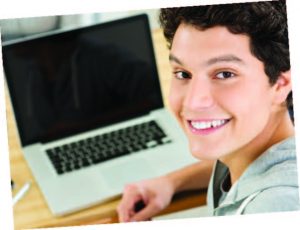

Many experts feel that homework strategies have failed to keep pace with the digital age. Finding answers is often a button-click away, while collecting information is like trying to drink out of a fire hose. The gates to knowledge have been flung wide open and, yet, when a child sits in front of a screen, there is no gatekeeper. Interestingly, upper grade homework has remained roughly the same since 1984—a bit under two hours—but what fills that time is, in many cases, dramatically different today than in the ‘80s. Some believe development of an Intelligent Tutoring System (ITS) will “replace” homework. An ITS is a computer program that gives students customized instruction and feedback in real time, with oversight by a teacher. These programs are becoming more prevalent in professional settings and may eventually find their way down to the grade school level.

Many experts feel that homework strategies have failed to keep pace with the digital age. Finding answers is often a button-click away, while collecting information is like trying to drink out of a fire hose. The gates to knowledge have been flung wide open and, yet, when a child sits in front of a screen, there is no gatekeeper. Interestingly, upper grade homework has remained roughly the same since 1984—a bit under two hours—but what fills that time is, in many cases, dramatically different today than in the ‘80s. Some believe development of an Intelligent Tutoring System (ITS) will “replace” homework. An ITS is a computer program that gives students customized instruction and feedback in real time, with oversight by a teacher. These programs are becoming more prevalent in professional settings and may eventually find their way down to the grade school level.

Harris Cooper, a Duke psychology professor, points out that people have been arguing about homework for a century. “The complaints are cyclical,” he says, “and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is about too much.”

Cooper adds that, back in the 1970s, the focus in American schools was on too little homework because we were more worried about global competitiveness. Wherever we stand as a parent or educator, we should prepare for the homework pendulum to continue to swing. But for now, although homework doesn’t appear to be all it was once cracked up to be, Do your homework! still resounds in many a U.S. household.

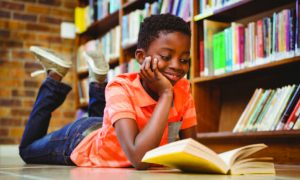

In the end, wherever you come down on the homework debate, and regardless of which mega-study you believe, there is one point all educators agree on—and cannot stress enough to parents—which echoes the conclusion of The Race to Nowhere: The single most important thing a child can do outside of school is read. Whether it is done for an assignment or as an escape, reading helps young people develop a sense of grammar and spelling, exposes them to new ideas, sparks the imagination and helps instill in them an intuitive understanding of communication.

MAKING HOMEWORK WORK

MAKING HOMEWORK WORK

As principal of the Benedictine Academy in Elizabeth, Ashley Powell is all too familiar with the battle of contention that has been raging for the past 10 years or so about the pros and cons of homework. She takes a structured approach on the “pro” side. For Powell, there is no value in simply requesting a review of what went on that day in the classroom:

“No busywork for homework…instead, I favor extending exploratory learning of subject matter through project and research assignments, rather than rote memorization.”

“There is just too much available online,” she adds, “so assigned topics can simply be Googled and regurgitated

“The key to making homework work for teachers (and students) is to know why they are assigning each night’s homework and to make sure it serves a valuable purpose.”

THE SWEET SPOT

THE SWEET SPOT

Finding the right balance of homework is a constant challenge, says Jayne Geiger, Head of School at Far Hills Country Day for 22 years and now Interim Head at The Rumson Country Day School. “We want children to take homework seriously, to think and reflect and produce their best work,” she says. “Yet we don’t want to overburden or overpressure them, especially with all of the outside-of-school activities students have now. We’re always looking for that sweet spot.”

Homework is a valuable tool, Geiger adds.

Homework is a valuable tool, Geiger adds.

“With younger children, it is used as an assessment tool. It helps us make sure that students understand the lesson. It reinforces what they’ve learned and gives them time outside the classroom to practice. For older kids, homework focuses more on context and application. Students might be asked to write an opinion on a topic discussed in class, work communally on a Google Doc, edit something they have already written, or do individual research and produce an original thought.”

For all ages, Geiger says, homework establishes good habits, including responsibility, organization and preparation. It also enables students to develop and practice their executive functioning skills.

But never forget, she adds, that reading “is still the best medicine!”