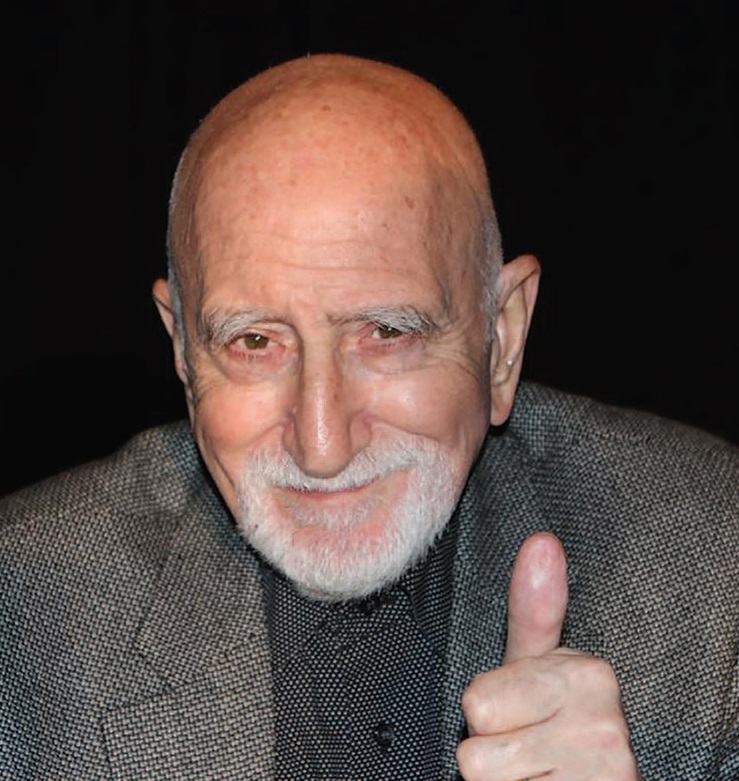

Dominic Chianese has been at this a long, long time. Longer, in fact, than even his most ardent fans probably know. Between playing the pivotal character of Johnny Ola in the first two Godfather movies and his unforgettable performance as Uncle Junior in The Sopranos, Chianese inhabited indelible characters in landmark films such as Dog Day Afternoon, All the President’s Men, And Justice for All, Fort Apache the Bronx and Unfaithful. He has also guest-starred on multiple Law & Orders and landed recurring roles on acclaimed series Boardwalk Empire, Damages and The Good Wife. His Broadway credentials stretch across three decades and include Oliver!, Richard III, Requiem for a Heavyweight and The Rose Tattoo. It was as a stage performer, actually, that Chianese first earned his show business spurs. Mark Stewart talked to Dominic about the craft of acting and his many roles, including that of Enzo on the new NBC ensemble drama The Village, which debuted on NBC March 19.

EDGE: How is film and television acting different from stage acting?

DC: It’s a different method of performance. You don’t use the body. It’s mostly in the face. If it doesn’t come out in the voice and the eyes and the facial expression, you fail.

EDGE: Did your years in the theater help you develop a screen personality?

DC: Yes, but I had to go through The Godfather first, which was my first real movie. I owe a lot to Francis Ford Coppola. That was 1971. It’s important to understand that I’d spent 20 years in the theater before I played Johnny Ola (left). I could never have made him believable without all that time in the theater… and if Francis hadn’t manipulated me when I was talking to Michael Corleone.

EDGE: How so?

DC: I started to “act” in front of the camera and you’re not supposed to do that. You’re just supposed to be the person. There’s a big difference—a different in the voice and a difference in the audience, which is the camera.

The camera does not lie, because the face is going to show everything.

EDGE: There were some impressive actors in The Godfather cast, including Marlon Brando and Al Pacino. Who else stands out among the people you’ve worked with?

DC: Oh, I’ve worked with some great actors. Al Pacino probably taught me the most. George C. Scott—who got me on East Side West/Side, my first TV show, in 1963—John Lithgow, Bobby Duvall, they all taught me something. They knew what the heck they were doing. I learned from a lot of great actors. And also my teachers: Phillip Burton and Wilson Mayer at Brooklyn College, and Walt Witcover, whose class I went to in 1962-63-64. He helped me understand what I was missing.

EDGE: How did you get into acting in the first place?

DC: My first inkling was when I was seven years old. I remember it like it was yesterday. But if you’re asking when I really put my mind to it, I was 20 years old. My voice—my love of music, of singing—is what got me into acting. I was in college, at Champlain College up in Plattsburg, New York. When I was 19, I was asked to join a group of a cappella male singers who were World War II veterans, older guys who were 26, 28, 30, on the GI Bill. They needed a bass so they gave me the job. We traveled to all the Ivy League schools. That is when I knew I was meant to do this. I knew I would definitely be performing the rest of my life. Less than a year later, the Korean conflict was starting and the college was closed down because the government needed a base. I returned to New York City. And as soon as I got off the bus, I went to the Jan Hus Presbyterian Church on East 74th Street and auditioned for Gilbert and Sullivan. I managed to land a chorus job and we toured for one whole year around the country. I was paid $110 a week, which was a fortune back in the ’50s.

EDGE: Did you think you could make a living on the stage?

DC: I spent about 10 years flirting with the idea that maybe this was not for me. The pressure was on to get an education. I ended up in 1961 with a degree from Brooklyn College, but while I was there I had Burton and Mayer, two great teachers who were experienced in the business. They encouraged me to no end. I remember I was cast in Chekov’s Three Sisters and thought I was doing a great job until the last scene. Burton said, “I don’t believe you when you’re saying goodbye to Masha. Maybe you shouldn’t be an actor”—in front of all the other kids [laughs]. Remember, I was 33 years old and had a lot of experience at that time, but I’d been doing mostly comedies and musicals. I think Burton and Wilson were in cahoots. They knew that I had natural ability creating characters and they wanted to get me to really understand the art, the technique.

EDGE: By technique what do you mean?

DC: I read a lot of Stanislavski. He developed The Method [of Physical Action] back in the 1930s. He said you can’t fake emotion. That’s all the method really is. It’s not a miracle cure or a set formula. He said you have to find your own way, really get in touch with something, so that you’re not faking the emotion. The imagination comes out in the voice. Everybody has to struggle a little to find their own technique, their “m-o”—whatever you want to call it. Once you do, you can be a lead actor or a character actor; it makes everything better, including your singing and your comedy. The analogy would be if you’re learning the piano and sit facing the opposite wall with your back to the keyboard, it’s going to be very hard to develop a technique. You have to face the piano, you have to stand a certain way and place your fingers on the keys a certain way, and that makes it easier. Most important is that, whether you’re in theater or in film, whether you’re acting in New York or a small town in Illinois, you’ve got to act the truth. You’ve got to really believe in the character and give it all you’ve got—put your concentration into the character. And then practice, practice, practice.

EDGE: Junior Soprano seemed like a challenging role. He was part manipulative psychopath and part demented old man, and you never knew how much of each you were seeing when you tuned in. Where did you draw your inspiration for that character?

DC: Junior was basically a New York-New Jersey kind of guy, so I drew him from my real life experience. Not as Mafioso [laughs] of course. I’m talking about his way of speaking. Being around so many Italian-Americans my whole life, it was easy to incorporate that into the character. Subconsciously, it was probably my father, my uncle and all the guys around the neighborhood. It was different than playing a farmer from Ohio, if you know what I’m saying…it came naturally to me.

EDGE: Junior was definitely losing it by the end of the series. Was that difficult to play?

DC: I’ve spent a good 30 years going to nursing homes and performing for people, so some came from that experience. But, again, a lot of it came from technique. You know, in order to play drunk in the theater, you have to play sober. You’re trying not to show that you’re drunk. So to play a guy with Alzheimer’s, you have to concentrate on something else, so it looks like you don’t know what you’re doing. I knew that people with Alzheimer’s have a way of not looking you in the eye, and of asking questions and not expecting an answer right back. There’s something missing.

EDGE: Everyone here in New Jersey basically adopted you from that role.

DC: I know [laughs] I know. Especially the people from Belleville!

EDGE: Tell me about your connection to New Jersey beyond the character you played in The Sopranos.

DC: Jersey is where my father did his bricklaying work. We lived in the Bronx but I used to go to Jersey all the time throughout the 1950s. I was always going to Jersey on the bus to lay brick with my father. We’d go to Newark. We’d go to Short Hills. We’d go to Paterson. We’d go to Clifton, where [Sopranos creator] David Chase lived as a little boy. I actually worked on the apartment he lived in, in 1952.

EDGE: Having been part of some legendary ensemble casts. I’m curious. Does your new show, The Village, have a live-theater ensemble feel to it?

DC: I never thought of that but, yeah, that’s definitely true. There is a good, collaborative feeling. The connections are like live theater. The writers are wonderful on this show. I’m very optimistic about The Village. It’s a show about real people, it’s not concentrated on a particular character. I just love the cast and crew on this show, I really do.

EDGE: What do you think the viewers will find most appealing?

DC: I think the fact that the issues are real. There’s a pregnant teenager, a returning veteran, immigration themes, an old man from a nursing home. It’s been very well written and represented here. It’s a show everybody can connect with no matter where you live. It’s about a community, and that’s what I like very much. We’re all in one building in Brooklyn. I grew up that way in the Bronx. We knew everyone from the first floor to the fifth floor. So for me it’s very familiar.

EDGE: Do you see a younger version of yourself when you look around the set?

DC: God no! [laughs] I do see great young actors. It takes me back to when I did my first TV show.

EDGE: So how do you strike a balance between the film and theater technique in this case?

DC: Film is different, but the imagination you use is the same—whether you do theater or film. In this case, the actual performance has to be attuned to the camera as opposed to the live audience. I feel very relaxed with The Village. When you’re relaxed and you’re connecting with your fellow actors, you’re just having a good time.