Researching your ancestors? Be careful…you just might find what you’re looking for.

By Mark Stewart

My college-age daughter’s curiosity got the better of her one day. She spit into a plastic tube and sent it off to Ancestry.com for genetic analysis. The results were almost exactly what we expected. No exotic forebears. No mystery genes. No colors of Benetton. For better or worse, she is pretty much what you would have called “American” more than a century ago.

Perhaps hoping to find something more scandalous, my daughter invited my wife and I to take the spit test, too. Back in junior high, I daydreamed through Biology, but I paid enough attention in Math class to know that our genetic results would not be any more revealing than hers.

But we did the spit test, anyway. While waiting for the results, I took a closer look at the Ancestry.com web site. I was impressed by the number of family-research documents available, as well as the program’s ease of use, and the constantly churning algorithms that relentlessly pump out little green leaves, which hold potential clues to the next generation and the next and the next and the next. We decided to take the plunge and attempt to separate family fact from family fiction.

Upper Case Editorial

In both of our cases, a certain amount of family lore has been passed down to us through a combination of old-school genealogical record-keeping and oral tradition. For instance, we knew that a branch of my wife’s family came to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the early 1600s. One unlucky member of that clan failed to convince a jury that he was not a witch. (His genetic line ended on another kind of branch, at the end of a rope.) As a boy, I was informed that one of my 17th century Massachusetts relatives was accused of being a witch, too. He must have had the same lawyer, because he was squashed under a large rock. Did one of my un-squashed ancestors know one of my wife’s un-hung ones? They seemed to be moving in the same circles, and almost certainly interacted at some point, perhaps even at one of these executions. As they used to say in Old Salem, nothing beats a good tree-hangin’ like a good rock-squashin’.

My parents gave me two interesting lines to follow. My mother was Jewish and my father was Unitarian. Unitarians are like honorary Jews in that they are constantly debating the fine points of their religion and are (at least in my experience) prone to unfathomable interior decorating choices. The Jewish half of my family came to America from Russia and Germany in the 1870s and 1880s. They got into finance, journalism and shirt-making. For the better part of a century, each branch aggressively pitched their profession to the young up-and-comers in the family—sort of like a reverse Shark Tank—hoping you would choose a fulfilling career at the bank, at the newspaper or in the sweatshop. I actually picked the bank first. The fact that I edit this magazine tells you what kind of a banker they thought I would make. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I guess I was foreclosed on. I was able to trace my mother’s people four generations to eastern Russia, where any further evidence of their lineage abruptly ended.

One of my father’s ancestors, however, left us a genealogical treasure trove. Starting sometime back in the 1800s, a maiden aunt began her own primitive version of Ancestry.com, writing to various family members and church parishes to compile information on her particular branch of the family. When she passed away in the 1930s, she dumped a trunk full of these documents on a bachelor uncle, who proceeded to write a family history, which he printed up and distributed to his siblings, cousins and nephews. Uncle Alex’s work focused on his own specific branch of the family, which was fortunate because, as we would discover, this was by far the coolest group. He also constructed a tree that traced several family lines back to England and Scotland, by way of Massachusetts.

CONVERGENCE

Given that England-to-Massachusetts also was the historical migration route of my wife’s family, we embarked on our genealogical journey suspecting—no, hoping really—that our family lines would cross in some long-ago time and place. The farther back in time the better, of course. I mean, we’re not hillbillies, right? Anyway, as we each worked backwards into the 1500s and 1400s and 1300s, it felt a lot like one of those old SAT word problems where two cars are driving towards each other and you have to figure where they meet.

One of the first to-do items on my wife’s bucket list was to nail down the particulars on four famous relatives: Morgan the Pirate, George Washington and Ralph Waldo Emerson. My daughter’s middle name is Morgan, in honor of Henry Morgan, a ruthless 16th century English privateer whose image now graces millions of bottles of mid-price spiced rum. Do we pull down any royalties from this family association? No. Which is probably why we are Scotch drinkers. The GW connection is through the Martha Custis family. George was Martha’s second husband, so the line theoretically branches off at that point. Our first president was sterile, having survived small pox as a young man, so he and the first First Lady never produced any offspring. Interestingly, my in-laws actually own a letter penned by Washington along with a lock of his hair. Receiving a lock of hair was like getting a signed, game-used baseball uniform back in the old days, so it’s pretty special. I recently met an antique collector who owns a beautifully preserved lock of Martha Washington’s hair. This sent me straight to the Internet to see where we are on this whole cloning thing. Apparently we’re not there yet, but check in with me 20 years down the road if you want a kid who’s handy with an axe, mostly tells the truth, and who can use a dollar bill as ID at the airport.

Upper Case Editorial

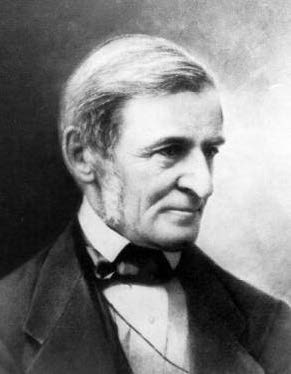

Unfortunately, our initial foray into the Ancestry.com process didn’t shed light either way on these two connections. As for the Waldos, however, my wife hit the jackpot. The poet Emerson (right), it turns out, was indeed a cousin. His line branched off several generations ago, but the Waldo men who preceded him—Jonathan, Zacheriah, Daniel, Cornelius, Thomas, and Pieter—stretched all the way back to the 1500s. Jonathan had the good sense to marry a woman named Abigail Whittemore in 1757. Her mother, also Abigail, had a great-great-great grandmother named Jane Payne, who was born in Kent, England more than 200 years earlier. In terms of record-keeping, the Payne family was what every genealogist hopes to find. The underlying truth of genealogy is that, if one goes back far enough, one is almost guaranteed to find a prominent ancestor— someone clever, rich and fertile enough to dodge the kind of awful Upper Case Editorial fate that extinguishes a family line. The very fact that you exist and are reading this article means that none of your ancestors died a childless, anonymous death. You are almost certainly descended from a person of means and influence…a duke, a lord, a princess, a baroness, or even a king and queen; the trick is finding the paper trail to prove it. In our case, it was the Paynes. The royal Paynes.

We picked through the birth and death information of the Payne family until we arrived at Sir Thomas IV. He lived and died between 1245 and 1288 in Bosworth, an important medieval market town in Leicestershire, a county in the Midlands region of England. Thomas’s wife was Mary Avis, three years his junior. They were my wife’s 21st great-grandfather and –grandmother. By 13th century standards, they were unquestionably people of considerable wealth and power, as were their progeny across many centuries. As we were marveling at the persistence of the Payne line, I recalled stumbling across a Phoebe Payne in my own family tree. Phoebe, my ninth great-grandmother, was born in Suffolk England in 1594, married a man named John Page when she was 27, and set sail to America a few years later. She lived to the age of 83, spending her final days in Watertown, Massachusetts. Could this be the same Payne family?

Upper Case Editorial

Lo and behold, I worked it out that Phoebe’s third great-grandfather, Thomas Paine, was a knight who lived in Market Bosworth in the 1400s. Going back a bit further, the family was apparently using the y form of Payne and Bingo! I landed on the aforementioned Thomas and Mary Payne. It took more than 20 generations, but the family that Tom and Mary launched into the world unwittingly curved back on itself when my wife and I tied the knot in 1987. Note to self: see if anyone owns the url www.lncestry.com.

Now joined in our ancestor search, my wife and I pushed back in time to see where the Payne family line led us. The root of the very English-sounding Paine and Payne, we learned, was actually French: Payns, the name of a small town about 100 miles southeast of Paris, which was called Payen in the Middle Ages. To an old European History major, that town rang a bell. Sure enough, our superstar common ancestor was Hughes de Payen (left), the co-founder and first Grand Master of the Knights Templar.

GAME OF THRONES

Well, you can’t do much better than Hughes de Payen, but we tried. Another branch of my family led to the Frankish king Hugh Capet, who was descended from Charlemagne. That sounds impressive until you do the math and realize that there are probably millions of people walking the planet who are descended from Charlemagne. Including every French person I have ever met. Yet another led to Berengar II, King of Italy from 950 to 961. His reign got off to a decent start but quickly went downhill after he got the bright idea to attack the Papal States. This did not sit well with Otto of Germany, the Holy Roman Emperor, who scooped up Berengar and his wife and threw them in jail, where they died four years later. I dropped the “Italian King” thing on the owner of our local pizza joint. I figured it might be good for a free topping or soda refill. No such luck

Upper Case Editorial

My family’s French connection had a better payoff. They apparently did quite well during what we call the Dark Ages, occupying important regional positions and holding enough land and money to finance small personal armies (a key to survival during those violent times). How this happened became clear when I began encountering titles like Senator and Prefect in front of their names. They were descended from politicians who held power in the province of Gaul during the death throes of the Roman Empire. Tracing the family back further, I discovered three actual emperors in my line- Activus, Gordian III and Gordian I—none of whom was particularly memorable. “GIII” as we now call Gordian III (above), was notable for his age. He was just 13 when he assumed full legal control of the empire in 239 AD. Since most 13-year-olds think they’re smarter than everyone else, I’m sure he did a fine job. GIII was married at 16 and at age 18 led his army to victory over the Persians in Mesopotamia at the Battle of Resaena. Alas, like most teenagers, he became convinced of his own invincibility and was defeated a year later when he pushed his luck by trying to grab more territory. The Romans lost the Battle of Misiche and young Gordian was either killed in the fight or murdered by his own officers

My wife had some interesting characters populating the non-French branches of her tree. Harald Bluetooth, King of Denmark and (briefly) Norway, was supposedly the first Scandinavian ruler to convert to Christianity. An earlier Norse ancestor, the famed Ragnar Lodbrok, is the inspiration for the popular cable series Vikings. We actually stumbled upon this genetic link shortly after watching the latest episode of the series, which stars Travis Fimmel, the Australian fashion model turned actor. According to legend, Ragnar was the warrior who led the Vikings into England and Europe, and possibly into the Mediterranean. Spoiler alert for series fans: The real Ragnar died in a pit of serpents. Yikes!

UHTRED VS. MALCOLM

In all of our genealogical research, the moment that generated by far the most excitement was the discovery that our families had first intersected 1,010 years ago. One of my more intriguing ancestors—and certainly the one with the best name—was Malcolm the Destroyer, King of Scotland. After assuming the throne in 1006, he launched a crech rig (translation: royal prey) on his Northumbrian neighbors. It was Scottish tradition at the time for newly crowned monarchs to attack their nearest weak neighbor. Malcolm picked on the newly founded city of Durham, which appeared to be defenseless. King Ethelred’s English army was occupied to the south fending off Danish raids. In his absence, my wife’s ancestor, a Northumbrian teenager named Uhtred, raised a ragtag force of fighting men from his neighbors in Bernicia and York and stunned the Scots on the battlefield—driving Malcolm back home with heavy losses. From that day forward, he was known as Uhtred the Bold. Uhtred’s reward for service to the king was the hand in marriage of his daughter, the radiant Princess Aelgifu.

The echoes of Uhtred’s achievement still resonate in the Stewart home. And by “echoes” I mean that my wife and daughters now remind me of this battlefield humiliation at the slightest of transgressions. Did you feed the cats, Malcolm? Did you pay the cable bill, Malcolm? Are those your socks on the floor, Malcolm? Who left the seat up, Malcolm?

After a thousand-plus years, you’d think maybe they could let it go. But if I’ve learned anything during this journey it is that, deep down, each of us is a product of our ancestors—good, bad and otherwise.

Somewhere up there, Uhtred the Bold is smiling. And Aelgifu is asking who left the seat up.

Upper Case Editorial

KNIGHT MOVES

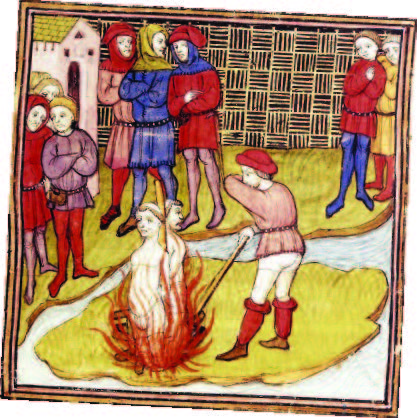

Thanks primarily to the History Channel, the Knights Templar have become a hot topic in recent years. They were a sophisticated and wealthy religious military order that flourished during the Crusades. They built forts across Europe and the Holy Land, earning a reputation as a formidable fighting force and also establishing one of Europe’s earliest banking systems. After Jerusalem was lost, the Templars fell out of favor with the Catholic Church. Philip IV King of France, deeply in debt to the Templars, used this as an excuse to erase his debt by hunting the knights down and executing them as heretics. Through torture, he hoped to discover where their fortune was housed, but none of the Templars talked. Treasure hunters are still trying to find it today. Some believe it includes the chalice used by Jesus at the Last Supper, i.e. the Holy Grail of Arthurian legend. By the way, Philip launched his attack on the Knights Templar on Friday, October 13, 1307—which some believe is the reason Friday the 13th is considered “unlucky.”

Editor’s Note: One of our more entertaining Ancestry.com finds was that my wife is descended from Penelope Stout, who was famously tomahawked by natives and left for dead after her ship ran aground at Sandy Hook in 1643. She survived the ordeal, had 10 children, and one of her descendants, Betsy Stout, married the author of the golf story on page 59. Betsy’s mother sold us our house. Small world.