You heard it here first.

By Mark Stewart

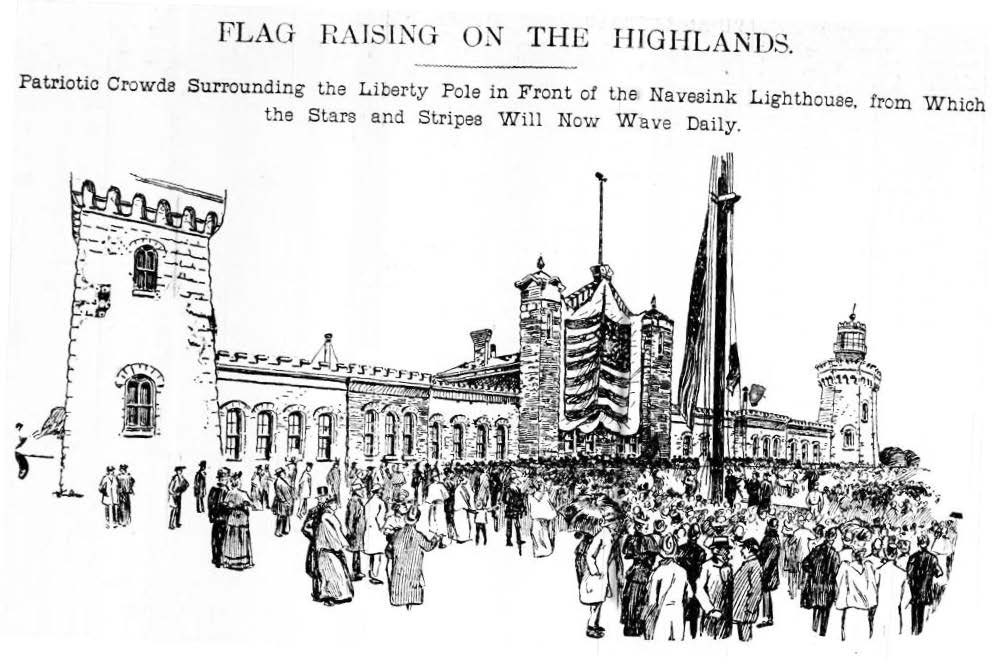

New Jersey is a land of famous firsts. According to the state.nj.us web site, we have played host to the first light bulb, first steam locomotive, first phonograph, first submarine, first drive-in movie, first electric guitar, and first football game. There are many more, of course. And yet, in this litany of #1’s, there is one fantastic first that is nowhere to be found in school textbooks or anywhere in our popular culture. On April 25th, 1893, during a ceremony atop the Navesink Highlands overlooking Sandy Hook, the Pledge of Allegiance was given as the national oath of loyalty for the first time.

How this day came together is a tale of passion, politics and power. How it ended up in the dustbin of history is a reminder of how fragile our cultural heritage can be.

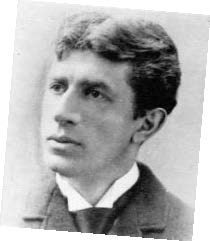

The Pledge of Allegiance looked a little different back then. It read: I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. Subsequent wording referencing the “United States of America” and “Under God” was added in the 1920s and 1950s, respectively. The original version was written in 1892 by Francis Bellamy (right) and published in The Youth’s Companion as part of a school program to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas

The Pledge of Allegiance looked a little different back then. It read: I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. Subsequent wording referencing the “United States of America” and “Under God” was added in the 1920s and 1950s, respectively. The original version was written in 1892 by Francis Bellamy (right) and published in The Youth’s Companion as part of a school program to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas

All images courtesy of Upper Case Editorial Services

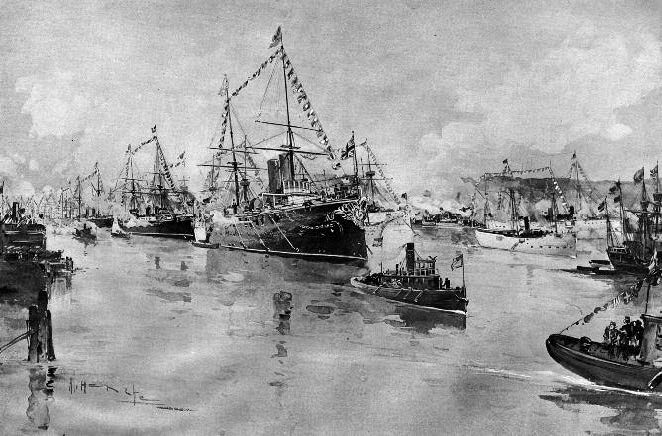

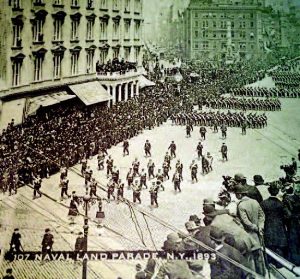

The Columbus Day ceremony was held on October 21. A mere seven months later—blinding speed by 1890s standards—Bellamy himself led a group of young men in reciting the Pledge during an event in New Jersey that might draw millions were it recreated today. It involved an unprecedented international naval review (above), followed by parades and parties in New York City that went on for days. The next time anything like it was even attempted was during the Bicentennial, in 1976, when the tall ships arrived

JERSEY BOY

JERSEY BOY

The key player of this story was not Bellamy, but William McDowell (right), a Newark-based financier whose business occasionally took him across the Atlantic. Upon each return to the U.S., McDowell marveled at the excitement that spread throughout the passengers as the first piece of American soil appeared. For the immigrants who filled steerage class, this moment was particularly meaningful. It marked the start of a new life. Roughly a third of Americans can trace some ancestry back to one of the people on these vessels. On a clear day, that first glimpse of America was the majestic Navesink Light Station, now known as the Twin Lights. Wouldn’t it be something, McDowell thought, if—before the two brownstone towers came into view—a gigantic American flag rose dramatically above the horizon? McDowell may not have been the first person to think of such a thing. However, he knew how to make things happen. His “Liberty Pole” plan first needed to gain the approval of the U.S. Lighthouse Board in Washington. The board was not known for its rapid decision-making. Fortunately, McDowell had friends in high places.

An ardent patriot, he was among a group of patriotic Americans who hoped to rekindle America’s national spirit, which had been profoundly fractured since the Civil War. In 1889, McDowell founded the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, or SAR for short. Its aim was to recognize and celebrate American ideals and culture. The group enjoyed rapid acceptance and growth, counting among its early membership several wealthy and influential business and political leaders. In the summer of 1890, SAR officers decided to take the “Sons” part of the organization’s name literally and denied membership to women. McDowell was appalled. His great-grandmother, Hannah Arnett, was a popular heroine of the American Revolution. In 1776, a group of men meeting in her Elizabeth home were preparing to take the oath of loyalty to Great Britain in order to protect their lives and property. Arnett overheard them and called them traitors to their faces. Mr. Arnett’s attempt to remove his wife backfired; she threatened to divorce him on the spot. Eventually she convinced the group to reject the oath. An editorial by Mary Smith Lockwood published in The

An ardent patriot, he was among a group of patriotic Americans who hoped to rekindle America’s national spirit, which had been profoundly fractured since the Civil War. In 1889, McDowell founded the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, or SAR for short. Its aim was to recognize and celebrate American ideals and culture. The group enjoyed rapid acceptance and growth, counting among its early membership several wealthy and influential business and political leaders. In the summer of 1890, SAR officers decided to take the “Sons” part of the organization’s name literally and denied membership to women. McDowell was appalled. His great-grandmother, Hannah Arnett, was a popular heroine of the American Revolution. In 1776, a group of men meeting in her Elizabeth home were preparing to take the oath of loyalty to Great Britain in order to protect their lives and property. Arnett overheard them and called them traitors to their faces. Mr. Arnett’s attempt to remove his wife backfired; she threatened to divorce him on the spot. Eventually she convinced the group to reject the oath. An editorial by Mary Smith Lockwood published in The

Washington Post asked, “Where will the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution place Hannah Arnett?” McDowell offered a response in the same newspaper, offering to help start the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Washington Post asked, “Where will the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution place Hannah Arnett?” McDowell offered a response in the same newspaper, offering to help start the Daughters of the American Revolution.

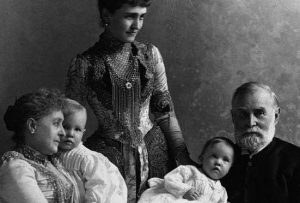

A few days later, with McDowell among the attendees, the DAR had its first meeting. Its President General was First Lady Caroline Harrison, wife of President Benjamin Harrison. With his new allies, the Harrisons (left), endorsing his plan to erect his Liberty Pole, McDowell had no problem getting a thumbs-up from the lighthouse board members—and little trouble raising the money to realize his dream. The Liberty Pole would be 135 feet tall—think of a car dealership flag on steroids—standing twice the height of the Twin Lights’ massive brownstone towers. The pole was constructed from two separate poles, hinged in the middle. The base was larger than most people could wrap their arms completely around.

HELLO, COLUMBUS

McDowell actually hoped to place Liberty Poles at the high point of every harbor where immigrants were flooding into America. This ambition (which ultimately went unrealized) paled in comparison to a proposal made by a group of Chicago millionaires that included familiar names like Swift, Armour, McCormick and Marshall Field. They convinced Congress to approve the creation of a Columbian Exposition, a World’s Fair to end all World’s Fairs. They managed to outbid New York for this honor—no small feat, considering the backers of the New York bid included J.P. Morgan, William Waldorf Astor and Cornelius Vanderbilt.

New York’s “consolation prize” would be the aforementioned week of patriotic celebrations, all kicked off by a flotilla of international warships. The vessels would gather at Hampton Roads, Virginia, and then steam north to anchor in Sandy Hook Bay the day before the naval review in New York Harbor. Once these plans were set and a date (April 26, 1893) picked out, McDowell scheduled his Liberty Pole dedication ceremony for the morning of April 25. The program would include the raising of the John Paul Jones flag timed to coincide with the passing of the warships.

The John Paul Jones flag (below) was the flag in America in

the 1890s. Its history stretched back to the 1779 seas battle where Jones refused to surrender his battered ship to the British, exclaiming, “I have not yet begun to fight!” Because the flag made famous by the Star-Spangled Banner was still in private hands, the John Paul Jones flag was considered one of the nation’s most treasured artifacts. It was transported from event to event by a Mrs. H.R.P. Stafford (right), and always drew a large and enthusiastic crowd. Special trains and steamers were scheduled to carry the many hundreds of people who wanted to travel from New York City and Northern New Jersey to attend the Liberty Pole dedication. At this point, McDowell had every reason to believe the Harrisons would attend. However, things didn’t quite work out as planned.

SELLING THE FLAG

Unbeknownst to McDowell, he had an important partner in Boston. The publisher of The Youth’s Companion, Daniel Ford (right), shared his belief that America needed to rekindle its patriotic pride. As the owner of the largest-circulating weekly publication in the country, Ford had the ability to promote this idea to his 500,000-plus readers. Of course, Ford was also a businessman. His nephew, James Upham, was in charge of the magazine’s premium department. Upham launched a plan in the late 1880s to sell flags by convincing the Companion’s legion of young readers that no schoolroom should be without one. The plan met with moderate success, but had yet to realize its potential. Then Francis Bellamy joined the staff.

Bellamy was an unlikely candidate for everlasting fame. He was a Baptist minister in Boston who had recently been relieved of his duties for pushing the Christian Socialist message too hard in his Sunday sermons. Fortunately for Francis, one of his congregants was Daniel Ford. Ford wasn’t a fan of the minister’s politics, but he admired the 36-year-old’s way with words and offered him a job at the Companion.Like McDowell, Ford had some influence in the White House. He encouraged President Harrison to okay a plan to make Columbus Day in 1892 a national school celebration…and to anoint The Youth’s Companion as the creator and distributor of the official program. Once Ford received the go-ahead, he assigned Bellamy to work with William Torrey Harris, head of the National Education Association. Harris was an admirer of the Prussian education system and believed the primary role of schools was to turn children into obedient citizens. Together, they hammered out a carefully orchestrated one-hour ceremony. At the urging of Upham, the program included the raising of a flag. Upham hoped that any school that did not yet have one would order a flag from his department. Taking this idea a step further, Ford and Upham also instructed Bellamy to pen a 15-second oath of loyalty for the children to recite. The program—including Bellamy’s Pledge of Allegiance—was published in the September 8,1892 edition of the magazine. On October 21, 1892, thousands of schools celebrated Columbus Day.

Bellamy was an unlikely candidate for everlasting fame. He was a Baptist minister in Boston who had recently been relieved of his duties for pushing the Christian Socialist message too hard in his Sunday sermons. Fortunately for Francis, one of his congregants was Daniel Ford. Ford wasn’t a fan of the minister’s politics, but he admired the 36-year-old’s way with words and offered him a job at the Companion.Like McDowell, Ford had some influence in the White House. He encouraged President Harrison to okay a plan to make Columbus Day in 1892 a national school celebration…and to anoint The Youth’s Companion as the creator and distributor of the official program. Once Ford received the go-ahead, he assigned Bellamy to work with William Torrey Harris, head of the National Education Association. Harris was an admirer of the Prussian education system and believed the primary role of schools was to turn children into obedient citizens. Together, they hammered out a carefully orchestrated one-hour ceremony. At the urging of Upham, the program included the raising of a flag. Upham hoped that any school that did not yet have one would order a flag from his department. Taking this idea a step further, Ford and Upham also instructed Bellamy to pen a 15-second oath of loyalty for the children to recite. The program—including Bellamy’s Pledge of Allegiance—was published in the September 8,1892 edition of the magazine. On October 21, 1892, thousands of schools celebrated Columbus Day.

Since every school now had a flag, most continued to have their students recite the Pledge of Allegiance every day. It became so popular that a movement started to make it a national oath for all Americans, not just kids. This concept attracted broad support, and not just because it might awaken the nation’s patriotic spirit. Ellis Island had opened a year earlier to accommodate the ever-growing influx of immigrants. Unlike, earlier waves, this one included a high percentage of people from Southern and Eastern Europe, many of them Jews or Catholics—religions that were misunderstood in the 1890s. Some questioned whether these new Americans would be loyal to the United States. An oath of allegiance thus held great appeal. President Harrison, who was preparing to run for reelection, thought a national oath was a superb idea.

Since every school now had a flag, most continued to have their students recite the Pledge of Allegiance every day. It became so popular that a movement started to make it a national oath for all Americans, not just kids. This concept attracted broad support, and not just because it might awaken the nation’s patriotic spirit. Ellis Island had opened a year earlier to accommodate the ever-growing influx of immigrants. Unlike, earlier waves, this one included a high percentage of people from Southern and Eastern Europe, many of them Jews or Catholics—religions that were misunderstood in the 1890s. Some questioned whether these new Americans would be loyal to the United States. An oath of allegiance thus held great appeal. President Harrison, who was preparing to run for reelection, thought a national oath was a superb idea.

The push for a national loyalty oath was not without its potential obstacles. Caroline Harrison, McDowell’s great friend, succumbed to tuberculosis that fall. Benjamin Harrison then failed in his bid to retain the presidency, losing to the man he had beaten four years earlier, Grover Cleveland. Fortunately, while Cleveland steered away from many of Harrison’s policies, he continued to support the idea of elevating the Pledge of Allegiance to national-oath status. The new president also gave his blessing to the great naval celebration in New York. Better still, Letitia Stephenson, the wife of the new vice-president (and grandmother of Adlai, the future UN ambassador) became the President General of the DAR.

With everything still on track for April, Ford, Upham and Bellamy—along with John Winfield Scott, who ran the Companion’s New York offices—began working with William McDowell to co-opt the Liberty Pole dedication on the 25th, including the reading of the Pledge of Allegiance during the flag raising ceremony.

RAIN RAIN GO AWAY

On the morning of the 25th, a cold and drizzly Tuesday, hundreds of dignitaries disembarked from railroad cars and excursion steamers and made their way to the top of the Navesink Highlands for the Liberty Pole dedication. Thirty-five naval vessels cruised past the lighthouse, with the lead ship firing a salute. An artillery crew from the New Jersey National Guard returned an ear-splitting volley. Mrs. Stafford displayed her famous flag and Bellamy led members of the Lyceum League in their historic recitation of the Pledge. The crowd performed the “Bellamy salute” as first described in his Columbus Day program. (During World War II, the salute was deemed too close to the Nazi salute and was changed to the current hand-over-heart version). An enormous “peace flag” covered the front of the lighthouse. The day concluded with speechmaking and poetry readings. The event was covered on the front page of all the New York papers the next day, and in various magazines for weeks afterwards. By any measure, it was an unforgettable occasion.

Except that, almost immediately, it was forgotten.

So what happened? The weather was lousy, making photography a challenge. There are a handful of images from the day, but few convey the importance or scope of the occasion. Near the end of the program, a steady rain began, scattering the crowd. Letitia Stephenson, who suffered from crippling rheumatism, did not show. Then came the much sexier news stories. The following day, the same warships assembled in New York for a review by President Cleveland. Days of parties and parades pushed the Pledge event off the front page. Harper’s Weekly created a spectacular six-sheet foldout feature that showed all of the ships in the harbor. A few days later, the Chicago World’s Fair opened, seizing the national consciousness.

More distractions followed, including a financial panic that spring. It was the worst in American history to that point, putting one in four Americans out of work. McDowell abandoned his Liberty Pole scheme and got back to business. Francis Bellamy continued to work at the Companion. And even though the Pledge of Allegiance would soon come to be regarded as America’s national oath of loyalty, no one could quite recall when and where its first recitation took place. As for the John Paul Jones flag, it was donated to the Smithsonian after the death of Mrs. Stafford. Curators there felt they did not have the necessary documentation to establish its authenticity. It was boxed up and never displayed in public. A few years later, the enormous Ft. McHenry flag made famous by the Star-Spangled Banner was donated to the Smithsonian, and the John Paul Jones flag was soon forgotten.

More distractions followed, including a financial panic that spring. It was the worst in American history to that point, putting one in four Americans out of work. McDowell abandoned his Liberty Pole scheme and got back to business. Francis Bellamy continued to work at the Companion. And even though the Pledge of Allegiance would soon come to be regarded as America’s national oath of loyalty, no one could quite recall when and where its first recitation took place. As for the John Paul Jones flag, it was donated to the Smithsonian after the death of Mrs. Stafford. Curators there felt they did not have the necessary documentation to establish its authenticity. It was boxed up and never displayed in public. A few years later, the enormous Ft. McHenry flag made famous by the Star-Spangled Banner was donated to the Smithsonian, and the John Paul Jones flag was soon forgotten.

There is a small but dedicated cadre of history bugs who have managed to piece together the origins and early days of the Pledge of Allegiance. They were deeply disappointed in 2014 when New Jersey celebrated its 350th anniversary. Not a word about the Pledge or the Liberty Pole or the great naval procession could be found anywhere in the official literature or on the state web site. And if all those amazing things aren’t part of the state’s official history, well, who’s to say they even happened at all?

Winston Churchill famously observed that, “History is written by the victors.” There is a lot of truth to this thought. Unfortunately, it fails to answer a critical question about the history that isn’t written…namely, who decides what is worth throwing away?

Editor’s Note: It turns out this is one piece of New Jersey worth saving. At the Garden State Film Festival in Atlantic City this spring, one of the nominees for Best Documentary is a 40-minute film narrated by Ed Asner entitled You Heard It Here First: The Pledge of Allegiance at the Twin Lights.