- 384 Springfield Ave. Summit NJ 07901

- (908) 277-0400

- visit website

- 317 Springfield Ave Summit NJ 07091

- (908) 277-4440

- visit website

- 24 South Ave. Fanwood NJ 07023

- (800)287-1793

- visit website

- 49 Summit Ave. Summit NJ 07901

- (908)273-3273

- visit website

- 549 Lexington Ave. Cranford NJ 07016

- (908)276-0900

- visit website

- 673 Audrey Dr. Rahway NJ 07065

- (732)215-4737

- visit website

- 333 Springfield Ave. Summit NJ 07901

- (908)464-8800

- visit website

- 1119 Springfield Rd. Union NJ 07083

- (908)686-6333

- visit website

- 24 Franklin Pl. Summit NJ 07901

- (908)273-3224

- visit website

- 1309 Kennedy Blvd Bayonne NJ 07305

- visit website

- 224 Elmer St. Westfield NJ 07090

- (908)232-5723

- visit website

- 90 Park Ave. Florham Park NJ 07932

- (973)755-2085

- visit website

- 110 South 20th St., Ste. 400 Philadelphia NJ 19103

- (866)488-2722

- visit website

- 89-91 Coit St. Irvington NJ 07111

- (800)941-5541

- visit website

- 1 Prince Rd. Whippany NJ 07981

- (800)545-1020

- visit website

In New Jersey, over-the-top gardening is no longer flying under the radar.

As forest and farmland have yielded to suburban sprawl, cities large and small across the country are reclaiming the urban landscape and becoming greener. Much of this green revolution is taking root high above street level, in the form of mini-parks and farms sprouting from the unlikeliest of places. Fueled by increased sustainability concerns and the burgeoning locavore movement, rooftop gardens are everywhere—out of sight but, increasingly, top of mind. Take our nation’s capital, for example. In 2012, Washington DC added 1.3 million square feet of rooftop garden space. From ancient times, when Nebuchadnezzar hung world-wonder gardens from the terraces of his Babylonian palace, rooftop gardens have captured our imaginations.

Even on a micro scale, what apartment dweller hasn’t tended herbs and potted tomatoes on a patio or fire escape? Well, now “agri-tecture” has become big business. In Brooklyn, rooftop farms are practically commonplace— beehives hum, chickens lay eggs, and organic vegetables begin their farm-to-table journey. The benefits of these Edenic aeries are manifold. Besides creating natural spaces and gardens, and optimizing space, the greening of roofs increase sustainability by reducing and reusing storm water, countering carbon dioxide, improving quality of life and the health of building occupants. To some, a green roof is a purpose; to others it is a passion. One extreme example is the Pasona, a human resource conglomerate in Tokyo. It’s headquarters is green inside and out with, a roof sprouting sweet potatoes, green interior and exterior walls, and a hydroponic rice-paddy foyer, which is harvested several times a year. The rooftop movement differs from country to country, and region to region, but make no mistake— it has definitely taken root here in New Jersey.

77 Hudson • Jersey City Installed by Let It Grow, of River Edge, NJ Four years ago, this rooftop garden was installed in Jersey City on an 11-story paring building structure between a KHovnanian condo high rise and an Equity Residential rental tower. This was a huge engineering feat, as much of the parkland material was installed by crane. Built on Styrofoam and two feet of fill on nearly an acre, it includes a pool, hot tub, dog run, African fire pit, children’s play area and even a landscaped hill. Undeterred when Hurricane Sandy struck and wind-stripped the soil (leaving roots exposed), the building replaced the landscape with heavier soils, planted more densely and installed a glass windshield. According to Randy Brosseau, KHovnanian Area President, it’s all worth it: “The garden adds a lot of value to our residents’ lives, whether using the facilities, enjoying the parkland or enjoying the view of the plantings. The green roof to many is a good reason to buy at 77 Hudson.”

NJIT Cafeteria Garden • Newark Installed in 2010 by “My Local Gardener” with Peter Fischbach and Julie Aiello You can’t get fresher or healthier food than the vegetables that are served at NJIT’s cafeteria. For three years, NJIT students and faculty have enjoyed farm-to-table vegetables harvested from an elevated 220 sq. ft. organic roof garden outside the student pub. On an existing “green” roof—which already had a faucet—the design team installed 10 recycled flower boxes and filled them with a light soil that wouldn’t weigh down the roof. According to NJIT chef Peter Fischbach (right), who envisioned the project with Julie Aiello, Director of Marketing and Sustainability for Gourmet Dining Services (GDS), the campus food purveyor, they plant rotating crops of healthy vegetables four to five times a growing season, including lettuce, beets, tomatoes, squash, broccoli, kale, collard greens, Brussels sprouts, peppers and peas. They also grow a large selection of herbs, which are used to season the food. Meanwhile, the garden has germinated other campus organic gardens. According to Fischbach, “The project has been so successful that it has inspired other colleges serviced by GDS—Seton Hall, Manhattan College, Kean University, FDU in Madison. And we are preparing to put in a garden at Bloomfield College.”

NJIT Cafeteria Garden • Newark Installed in 2010 by “My Local Gardener” with Peter Fischbach and Julie Aiello You can’t get fresher or healthier food than the vegetables that are served at NJIT’s cafeteria. For three years, NJIT students and faculty have enjoyed farm-to-table vegetables harvested from an elevated 220 sq. ft. organic roof garden outside the student pub. On an existing “green” roof—which already had a faucet—the design team installed 10 recycled flower boxes and filled them with a light soil that wouldn’t weigh down the roof. According to NJIT chef Peter Fischbach (right), who envisioned the project with Julie Aiello, Director of Marketing and Sustainability for Gourmet Dining Services (GDS), the campus food purveyor, they plant rotating crops of healthy vegetables four to five times a growing season, including lettuce, beets, tomatoes, squash, broccoli, kale, collard greens, Brussels sprouts, peppers and peas. They also grow a large selection of herbs, which are used to season the food. Meanwhile, the garden has germinated other campus organic gardens. According to Fischbach, “The project has been so successful that it has inspired other colleges serviced by GDS—Seton Hall, Manhattan College, Kean University, FDU in Madison. And we are preparing to put in a garden at Bloomfield College.”

Revel • Atlantic City Installed by Cagley & Tanner of Las Vegas Last summer, Revel, the upscale resort in Atlantic City, opened a two-acre Sky Garden to recall the beauty and ambiance of the great Atlantic seaside resorts of the past—following the practice of situating a resort in a garden that descends to the beach. While the hotel’s architecture is 21st century, the designers sought to enhance the vista with a mix of nostalgia and modern ingenuity. This homage to the lawns that swept down to the ocean begins, in fact, at 114 feet above sea level, and is landscaped for seasonal interest—with 20,000 plants ranging from native sea grasses to Japanese Black Pines that create a Pine Grove surrounding an outdoor fireplace. (Planting the large pines required creating a deep recessed area under the roof surface to allow for root growth.) Their hard work paid off, as the garden successfully weathered the forces of Sandy.

Extra Space Storage • North Bergen Extra Space Storage, with its landscaped roof, definitely wins the “good neighbor award.” While only the on-site manager has access to Extra Space Storage’s rooftop garden, the company installed the nearly half-acre landscaping to “ensure an aesthetically pleasing view for all for the high-rise condo properties that surround our building,” explains Clint Halverson, Vice President for Corporate Communications and Investor Relations. The mechanics of creating a rooftop garden involve a number of variables: structural support, irrigation, installation stories above ground level, wind buffers and— not the least of concerns—waterproofing, root barriers and drainage. However, the rewards also are significant. Gardens insulate, reducing heating and cooling costs up to 30%. And they shield a building from urban noise. In the end, though, the greatest selling point of a rooftop garden is its aesthetic and recreational appeal. In a world of concrete, glass and steel, we welcome anything that speaks so eloquently to our senses and spirit.

Editors Note: Sarah Rossbach is the author of Feng Shui: The Art of Chinese Placement, which was described by The New York Times as the “bible of the practice.”

The Big Build Up

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

Is there a second story in your future?

Moving up doesn’t have to mean moving out. More and more, owners of one-story dwellings in the Garden State have been addressing their space issues by adding a second floor. Yes, it’s expensive. And yes, it’s messy. But in many cases, “building up” makes more sense than shopping for a new home. There are any number of reasons to add a second story to your current home but, needless to say, they are all related to space. The big question is Why go through the time and trouble to do so if you could just buy something that suits your needs? Well, for starters, that would mean having to put your own (presumably undersized) house on the market for sale, or as a rental property. So there’s a major hassle factor. Also, you may be locked into a great mortgage rate in your current abode, or for some reason be unable to qualify for a favorable rate on a new property.

The most common answer to Why build up? is that you love your home, your neighborhood and your neighbors, and are willing to put up with the inconvenience in order to stay put. From an architect’s perspective, the primary challenges of designing a new home involve understanding a wide range of variables, and then reconciling them with the desires of the homeowner. The most cost-effective solution almost always involves using the existing foundation and exterior walls. A talented architect, working in concert with a structural engineer, should be able to check off most of the items on your list. For older homes—or homes that were constructed cheaply to begin with—there are going to be structural issues. However, rarely are they insurmountable. Hopefully, the solutions won’t bust your budget. Consulting with that structural engineer is a must. Understanding local building codes is obviously important, too. You’d be surprised to see what’s on the books in your town when it comes to staircases, ceiling heights, and room dimensions. The engineer sho uld also be able to tell you with absolute certainty whether you can get the job done without tearing out your first-floor ceilings. This greatly reduces the mess and expense. From a builder’s perspective, adding a second story isn’t all that different than building from the ground up.

uld also be able to tell you with absolute certainty whether you can get the job done without tearing out your first-floor ceilings. This greatly reduces the mess and expense. From a builder’s perspective, adding a second story isn’t all that different than building from the ground up.

In most cases, the addition fits neatly atop the current first floor, and uses the existing exterior walls as the primary support. In some cases, a modular addition can be employed, which offers significant savings. It’s partially assembled on the ground and then lifted into place with a new roof, or under your existing one. The interior finishing work is not all that different than any other home remodel job. From a realtor’s perspective, it usually makes sense to find something with more space in the same neighborhood. Especially in depressed markets, finding more space is cheaper than creating it. Of course, that generates a couple of potential commissions, but the facts do bear out this position. The addition of a second story rarely recoups the investment when it’s done. On average, in suburban areas, at least, the number seems to be around two-thirds. In other words, a $150,000 second-story addition may only increase your home’s value by $100,000. This is math you may be willing to live with, but it’s math you should do (with a competent and trusted realtor) before going all-in. Among the classic mistakes homeowners make is assuming their current attic construction will support a second floor. It almost certainly won’t.

Attics are not built to handle second-story traffic. There is no cost savings to be had here—it’s not as simple as simply raising the roof and converting gloomy storage space into a bright and airy second story. Also, that attic staircase you’d planned on repurposing is unlikely to pass muster with local building codes when it connects the two new living spaces. If you do not currently have a staircase in your home, keep in mind that it will have to go somewhere on your first floor—and that you may lose a room. Speaking of which, the plumbing, electric, heating and air conditioning systems that serve your first floor will need a lot more space on the first floor to make it up to the second floor. Some homeowners end up opting for an entirely new and separate set of systems for the addition. Keep in mind that part of the expense of adding a second story almost includes a new furnace, AC unit and water heater. Another consideration is what you’ll need to do to the exterior of your home to make it come together. That re-siding project you’ve putting off the last few years? Now’s the time to squeeze the trigger.

Y ou should also think about pulling together the interior. Indeed, a less common but still-critical mistake homeowners make is failing to really think through how the new second story will relate to the “new” first story in terms of how the entire home is used. Moving bedrooms to the second floor opens up all sorts of possibilities on the main level. If you determine how you might be using the first-floor space in the future, you can leave yourself a lot of options, especially if a new kitchen is part of the long-term plan. When it’s all said and done, a basic second-story addition will eat up a half-year of your life and cost you at least $125 to $150 per square foot, soup-to-nuts, plus professional fees. Depending on your desired finishes and a handful of other variables, the price tag of a 1,000-foot addition is likely to be in the neighborhood of $150,000. Does that make sense in your neighborhood? Ultimately, that’s a call you’ll have to make.

ou should also think about pulling together the interior. Indeed, a less common but still-critical mistake homeowners make is failing to really think through how the new second story will relate to the “new” first story in terms of how the entire home is used. Moving bedrooms to the second floor opens up all sorts of possibilities on the main level. If you determine how you might be using the first-floor space in the future, you can leave yourself a lot of options, especially if a new kitchen is part of the long-term plan. When it’s all said and done, a basic second-story addition will eat up a half-year of your life and cost you at least $125 to $150 per square foot, soup-to-nuts, plus professional fees. Depending on your desired finishes and a handful of other variables, the price tag of a 1,000-foot addition is likely to be in the neighborhood of $150,000. Does that make sense in your neighborhood? Ultimately, that’s a call you’ll have to make.

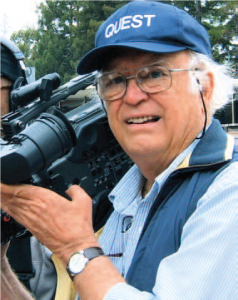

An award-winning documentarian is leaving his mark on the Lambertville art scene

Bill Jersey

How do you segue from a gig as Art Director of the 1958 sci-fi potboiler, The Blob, to become one of the pioneers of the cinema vérité movement? If your name is Bill Jersey, you grab your camera, prop it on your shoulder and never look back. The legendary documentary filmmaker—now a robust 85 and a fixture in Lambertville arts circles—laughs that his Fundamentalist upbringing on Long Island hardly predicted his future stature as a cinematic trailblazer. In fact, Jersey never saw a film until he ran off to join the Navy. He was 17. “The first film I saw was on the USS Arkansas, a battleship that I went on to the South Pacific,” recalls Jersey from his home office along the banks of the Delaware River. “I enlisted in the Navy to get away from home. It was my escape.” The G.I. Bill helped bankroll his undergraduate studies in art. “Studying art in college was the only thing I could do that was acceptable to my parents,” he says. “I couldn’t go to the movies, dance, drink, smoke, swear or play cards.”

After graduation, he put his paint box in mothballs and tested the waters at Good News Produ ctions, a religious film company in Valley Forge, PA. “I told them I didn’t know anything about film,” says Jersey. “They hired me anyway, and I learned how to be an art director. I also realized how little I knew.” So he headed West to graduate film school at the University of Southern California. Graduating in 1956, he dipped his toe in the B-movie drama pool as Art Director of The Blob, Manhunt in the Jungle and 4D Man. But he was primed for documentaries. “There was something about wanting to connect to people in the real world and finding them much more interesting than working with actors with a script,” he says. “If you really care about people, they will know it, and they will open themselves up to you. And that’s what makes a good documentary.”

ctions, a religious film company in Valley Forge, PA. “I told them I didn’t know anything about film,” says Jersey. “They hired me anyway, and I learned how to be an art director. I also realized how little I knew.” So he headed West to graduate film school at the University of Southern California. Graduating in 1956, he dipped his toe in the B-movie drama pool as Art Director of The Blob, Manhunt in the Jungle and 4D Man. But he was primed for documentaries. “There was something about wanting to connect to people in the real world and finding them much more interesting than working with actors with a script,” he says. “If you really care about people, they will know it, and they will open themselves up to you. And that’s what makes a good documentary.”

In 1960, Jersey launched Quest Productions and began attaching his own vision to a slate of industrial films for corporate giants Western Electric, Exxon and Johnson & Johnson. He won his first Emmy Award in 1963 for directing Manhattan Battleground for NBC-TV’s DuPont Show of the Week. Ever the maverick, Jersey never felt compelled to toe the company line. “I don’t do ‘promotional’ films,” he emphasizes. “I found you have to really try to understand the company better than they do. I try to give them what they need, even though frequently they would not describe their needs that way. The only way is by taking the big risk, the hero’s journey, to look at things honestly.” Jersey got a chance to kick-start that journey when he filmed A Time for Burning in 1965. Commissioned by Lutheran Film Associates, the cinema vérité Civil Rights documentary records the failed mission of young Lutheran Pastor  Bill Youngdahl to integrate a large, all white church in Omaha.

Bill Youngdahl to integrate a large, all white church in Omaha.

A Time for Burning tracks the crises of conscience and faith that arose when the minister encouraged his white congregation to engage with black congregants from a neighboring Lutheran church. Despite his gentle, faith-based approach, Pastor Youngdahl’s impact on Omaha’s Lutheran community proved to be, as Jersey predicted, incendiary. “The Lutherans wanted a film about the church and race,” he recalls. “So I found a minister who had an integrated church in New Jersey and was being called to a big al lwhite church in Omaha. I knew he’d want to integrate it, and that there could be some tension. I met with the minister, who said, ‘You can do a film here, there’s no problem.’ And I thought, ‘Well, that’s what you think.’ “Look,” adds Jersey, “the church didn’t need a film about a minister getting kicked out of his church.

They needed a film about how wonderful the church was, and how Jesus was going to be loving to everybody.” Unencumbered by a script, narrator, captions, timelines or media stars and filmed with a minimal crew, A Time for Burning became a benchmark Civil Rights documentary that subsequently received critical acclaim, an airing on most PBS stations nationwide, and an Oscar nomination. It thrust Jersey to the forefront of the cinema vérité movement where he has remained for almost 50 years,  producing and directing independent documentaries on such hot button issues as racism, criminal justice, gang violence, AIDS, Communism and integration. “For me, cinema vérité means letting the truth drive the story,” explains Jersey. “I don’t set out to prove anything— as many documentarians do. The difference between me and others is that I believe in being a participant observer. I explore options with my participants in the belief that our encounters will open them up to seeing more of themselves—not to see themselves as I see them. It’s a tricky business; but in my view, it’s an essential part of being a documentarian.”

producing and directing independent documentaries on such hot button issues as racism, criminal justice, gang violence, AIDS, Communism and integration. “For me, cinema vérité means letting the truth drive the story,” explains Jersey. “I don’t set out to prove anything— as many documentarians do. The difference between me and others is that I believe in being a participant observer. I explore options with my participants in the belief that our encounters will open them up to seeing more of themselves—not to see themselves as I see them. It’s a tricky business; but in my view, it’s an essential part of being a documentarian.”

A Time for Burning continues to be a staple in film schools where Jersey is a sought-after guest lecturer. In 2004, the film was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the prestigious National Film Registry. Despite his résumé of more than 100 films, Jersey—with typical self-effacement—claims to have lost count of the awards and honors he’s received. In the mix are names like Emmy, Oscar, Peabody, DuPont Columbia, Christopher, Gabriel, Cindy and Cine Golden Eagle. Jersey continued in the winners’ circle this spring, garnering a Peabody Award for Eames: The Architect and the Painter. The documentary profile of visionaries Charles and Ray Eames had a healthy theatrical release in late 2011 prior  to debuting on PBS as part of the American Masters series. It should come as no surprise that Bill Jersey—father of five and grandfather of five—has no intention of winding down. “On the contrary, I’m winding up!” he says with relish, as he now juggles two careers instead of one.

to debuting on PBS as part of the American Masters series. It should come as no surprise that Bill Jersey—father of five and grandfather of five—has no intention of winding down. “On the contrary, I’m winding up!” he says with relish, as he now juggles two careers instead of one.

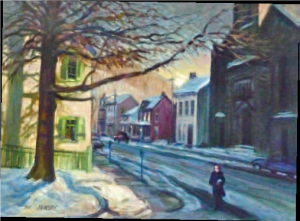

With a new two-hour documentary in the works—The Failed Revolution—about the history of the Communist Party in the U.S., Jersey has also enthusiastically returned to painting. He takes full advantage of the lush natural landscapes in and around his home, a charming 19thcentury boat builder’s cottage in Lambertville on the canal bordering the Delaware River. “We love it here!” he enthuses. “And since my passion is painting, this is a great community to be a part of.” A fan of painter Edward Hopper—“his use of light”— Jersey brings his filmmaker’s eye to his painting: “One of the reasons I like landscapes so much is I like being  out in the country where the light is changing. If you’re painting a river, you’re painting something in motion. The light does not sit there for you. That lovely shadow from the rooftop that you love will be gone in 15 minutes. It’s a very alive process.”

out in the country where the light is changing. If you’re painting a river, you’re painting something in motion. The light does not sit there for you. That lovely shadow from the rooftop that you love will be gone in 15 minutes. It’s a very alive process.”

Sharp and witty with energy to burn, Jersey spent his 85th birthday with his wife, Shirley Kessler, painting in Italy and enjoying his favorite sport—fine dining. He’s quick with a quip when asked if “80 is the new 60”. “Not in the knees,” he laughs, “but in terms of intellect and one’s capacity to engage in meaningful interaction with the world. That’s what keeps me young. Every day I read The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times because those are two perspectives I need to understand the world.” “Life is good!” admits Jersey, the eternal optimist. “With all my aches and pains, I am grateful—that’s the magic word—for every minute of every day!” There are Jersey tomatoes, Jersey Boys and Jersey Devils, but there’s only one Bill Jersey.

All photos courtesy of Bill Jersey

Editor’s Note: Bill Jersey’s paintings will be on exhibit at a one-man show at the Bank of Princeton Gallery in Lambertville, NJ, November 15 through December 15, 2012. A Time for Burning and Eames: The Architect and the Painter are available on DVD. Judith Trojan has written and edited more than 1,000 film and television reviews and celebrity profiles for books, magazines and newsletters. Her interviews have run the gamut from best-selling authors Mary Higgins Clark, Ann Rule and Frank McCourt to cultural touchstones Ken Burns, Carroll O’Connor, Judy Collins and Caroll Spinney (aka Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch). Follow Judith’s media commentary in her FrontRowCenter blog at judithtrojan.com.