Will your house become a virtual doctor’s office?

by Caleb MaClean

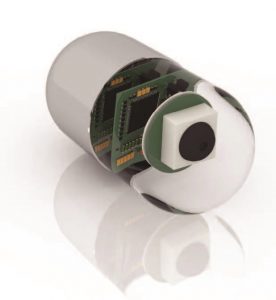

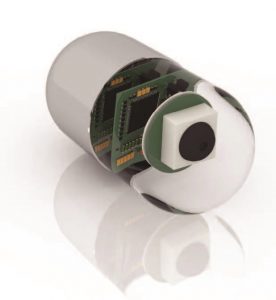

In November 2017, the Food and Drug Administration approved Abilify MyCite, the first “digital” pill. The pill, made of silicon, magnesium, and copper, contains a sensor no bigger than a grain of sand. It communicates with a patch worn by the patient, which then trans its medical data to a smartphone app, which in turn uploads it to a database that’s accessible to a patient’s doctor (and also family members). The sensor is activated when it interacts with stomach acid and transmits the time the pill is taken, as well as the dosage.

Abilify is a medication that treats bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia, all of which demand that a patient stay on schedule with medication. The digital pill makes for easy monitoring by a third party. Although there are some inherent privacy issues that will probably need to be worked out, the big picture for healthcare is big indeed: By some estimates, the improper or unnecessary use of medication costs the industry $200 billion annually. To wrap your head around that number, consider that the total amount of property taxes paid by New Jersey homeowners in 2018 will probably be about $30 billion. With that much money on the table, you’d better believe a flood of digital pills is on the horizon.

www.istockphoto.com

This is just the beginning of a revolution that will move more and more elements of traditional medicine into the home—to the point where, one day, more doctoring will be done through digital housecalls than in medical practices. Which is why, in 2017, the FDA created a new unit devoted entirely to digital health.

It is being staffed with engineers well-versed in software development and artificial intelligence, who are able to deal with the steadily growing flow of medical technologies that require FDA approval. While certain parts of the federal government maneuver at a snail’s pace, the FDA is changing its culture to deal with the day in the not-too-distant future when machines will be monitoring and regulating a huge part of the healthcare industry. The FDA has long considered medical “apps” outside of its purview and thus the vast majority are currently unregulated. As more and more traditional medicine moves out of the doctor’s office and into our bedrooms and living rooms, that will need to change. And soon, for all of our sakes.

The digital pill is, in its own way, a forerunner of how our homes will become part of the pharmaceutical industry Within a few years, 3-D printers will be integrated into millions of American homes, plugged right into our smartphones and laptops. At the moment they are novelty items, but the capability to “print” pills on an as-needed basis may make them as common as home-testing machines for blood glucose or coagulation levels. Besides the cost savings and the convenience factor, this technology could also create pill shapes that release medications at different rates. For patients who need medications “tweaked” regularly, 3-D printers would be a godsend.

DOCTOR, DOCTOR

The digital housecall will be commonplace years before the printed pill. Ask people who work in the tech industry and they’ll tell you it can’t come soon enough. Besides the new FDA unit, there is already a trade organization promoting digital medical consultations, the American Telemedicine Association. Several insurance carriers either cover, or say they plan to cover, webcam exams and consultations. At the moment, digital housecalls are being conducted primarily in rural areas, via smartphone and Skype. The visual component is key; according to health insurance giant Aetna, the error rate is one-fifth that of voice-only doctor consultations.

Actually, the digital housecall is nothing new. It’s around 10 years

The initial driver was distance. In places like Maine, where a single hospital may cover hundreds (or even thousands) of square miles, keeping patients off the road is a huge priority. Maine, in fact, was one of the proving grounds for telemedicine. Doctors there used telemedicine in a wide range of situations, including burn and trauma cases, where victims had to be helicoptered in for emergency treatment. They found they could begin “treating” those patients en route or, in some cases, on the scene.

www.istockphoto.com

Going forward, the driver of telemedicine will be cost (or more to the point cost savings). A doctor can see more patients digitally than in an office, which creates money saving— and money-making—efficiencies. Patients, on the other hand, benefit financially, too. They save time and money by staying at home or at work during a medical consultation. The necessity of hands-on contact is certainly an issue, but as more “connected” monitors and diagnostic devices come online, the need for doctors and/or medical staff to be in the same physical space as their patients will decline. Right now, insurers estimate that only about 20 percent of visits to a GP actually require a GP. Think about your last visit to the doctor’s office: How much physical contact did you have with your doctor? How much of your check-up was off-loaded to a nurse of staff member? Much of what a doctor does is ask a series of questions and listen carefully to your answers—which can be done on a screen.

So how exactly will this work?

Based on what already works in the places that telemedicine has a track record, it’s not difficult to paint a realistic picture. Patients will register online with the primary care physician or medical group that currently serves them, or possibly with a hospital center such as Trinitas. Though the particulars are likely to vary somewhat from insurance plan to insurance plan, patients will make appointments to interact with doctors (or other healthcare workers) in a space in their house or apartment where they can see and hear each other, and where the patients have access to biometric devices that plug into a smartphone or computer. Given that most of the equipment in a doctor’s office—and for that matter in a hospital—already “talks” to computers, there is no reason why simpler, cheaper home versions couldn’t be made available to patients with chronic illnesses or other conditions that require periodic monitoring. Right now, people with artificial heart valves already test their own blood weekly in order to tweak their Warfarin dosage (a famously moving target) and report PT/INR levels to their cardiologists. Five years ago, the home equipment was expensive and cumbersome; most patients had to drive to a lab to get their blood drawn and tested. Now the device is the size of a Game Boy. Five years from now, or perhaps much sooner, the next generation of these monitors will feed data directly into the cardiologist’s computer.

As hospitals cross the digital divide, they are likely to find telemedicine a force-multiplier, as well as a profit center— especially if they offer distinct specialties. For example, there are patients who travel many hours multiple times a week from surrounding states to see the wound-healing specialists at Trinitas. Not all of those trips are related to procedures performed on-site; a fair number are progress-checks and dressing changes that could conceivably be conducted without a patient leaving the home.

DIGITAL DOC-IN-A-BOX

www.istockphoto.com

If you think about it, the reduced need to physically visit a doctor’s office cuts both ways—if the patient can stay at home, why not the doctor? Your digital housecall may be conducted by a physician working remotely, too—perhaps from his or her own home or home-office. There are, in fact, thousands of doctors who already work this way. Many are part of existing telemedicine groups. These companies treat hundreds of thousands of patients and are constantly tweaking how their platforms deliver healthcare to under-served or isolated communities.

At the moment they are kind of like virtual “Doc-in-a- Boxes,” bringing basic diagnostic services into homes. But make no mistake about it…they have their sights set on a bigger piece of the pie.

MDLive, which began offering digital housecalls almost a decade ago, recently added dermatology to its roster of services. It did so by partnering with an existing company called Iagnosis, an online skincare company that developed a platform called DermatologistOnCall. “Teledermatology” (they need to work on that name, by the way) makes sense on a lot of levels.

First, it is a very visual branch of medicine, from training to practice, so it lends itself to a camera and screen. Second, how long do you have to wait to see a dermatologist on your current insurance plan? California-based SnapMD, a relative newcomer to the industry, just launched an app that enables Spanish-speaking patients to communicate with doctors who don’t speak Spanish, and vice-versa. Wall Street is watching companies like these very carefully, trying to divine where the “tipping point” is for the industry. Some believe it is coming in the next year or two.

HOME, SMART HOME

Homebuilders also are paying close attention to this space. They are already partnering with tech innovators on ways to make their homes “smarter” and recognize that, as Baby Boomers age, telemedicine will become a part of their lives. Some builders, in fact, may be thinking really big: Not only will future housing units double as doctors’ offices, by incorporating medical hardware and software, they may double as “doctors,”

The first group to break ground on this idea was a research team at the University of Rochester. Back in the early 2000’s, they initiated a project called the Smart Medical Home. Its goal was to develop interactive technology for home healthcare. It brought together doctors and engineers from the university, Rochester Medical Center and the Center for Future Health. Over the next few years they designed living spaces that actively assisted patients with dementia and Parkinson’s. A Personal Medical Monitor was built into one of the walls. It featured an avatar that interacted with residents and answered questions about medication and symptoms of illness. Sensors located around the structure were designed to monitor the resident and could alert his or her doctor if it detected a change in vital signs.

www.istockphoto.com

The home-as-doctor concept has continued to pick up steam in the ensuing years, as computing power and artificial intelligence have doubled, doubled again and doubled again. In 2015, a story in Healthcare IT News on smart medical homes reviewed a number of machine-tomachine (M2M) health devices in development for home use, including monitors built into footwear that can detect a limp or shuffle that may be a symptom of a more serious illness—and transmit this information through the home. In 2017, the same Center for Future Health in Rochester received funding for the development of tiny, wearable health monitors that transmit data to a base station in the home. The monitor incorporates “predictive” health software that can spot developing health issues, manage daily routines and intervene in the case of an emergency. The system constantly evaluates activities, motion, breathing, the sound of the wearer’s voice and how they all intersect.

It is not just the home and health industries that are working toward this goal. At the 2018 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, CNET held a forum entitled The Invisible Doctor. A panel of tech, medical and insurance industry experts explained how everyday items—from smartphones to home appliances—could potentially be part of a health-monitoring network keeping us connected to our doctors through our smart homes.

Some things, however, simply must be done in a doctor’s office or hospital setting. So the digital housecall will never replace brick-and-mortar medicine. That’s not the idea, anyway. The goal is to make the “front line” of healthcare more time- and cost-efficient and to make doctors more accessible to more people in more places.

Just as important is the byproduct of that goal: To give doctors access to patients before small problems become big ones.

NATURAL DISASTERS

Telemedicine has the potential to play a major role in disaster relief efforts. One of the first things that happens in stricken areas is the collapse of the healthcare infrastructure. Hospitals may keep their doors open and restore power during a crisis—they are built to do this— but are unlikely to be able to cope with the ensuing spike in demand from scores of the sick and injured. In these cases, access to virtual doctors and diagnostic services would prove invaluable in coping with the patient surge at brick-and-mortal hospitals. Down the road, these relationships could conceivably extend to remote surgical procedures, performed by surgeons in daVinci pods like the ones at Trinitas, working on patients in OR’s thousands of miles away.

OLD SCHOOL

OLD SCHOOL

One of the great debates around digital doctor visits is how easily older patients will take to the new paradigm. The implication is that individuals over a certain age are intimidated by technology, or are total Luddites. That may be, but balanced against the comfort level of seeing your own doctor in your own home, it may be less of an issue than critics claim. As home/medical technology advances it will, by definition, become simpler to use, with fewer buttons to push and procedures to follow. You can already get a TV remote you can talk to…biometric devices that follow voice commands can’t be too far behind.

TELEMEDICINE HURDLES

For digital medicine to become fully integrated into the healthcare system, two major challenges will have to be continually addressed. While the hardware end of the business will become faster, better and cheaper, the software may struggle to keep up—and not just the software that runs diagnostic tools. As is currently the case with in-office visits, everything a doctor does will have to be coded and entered into a database used for billing, coverage eligibility, deductibles, referrals, and reimbursements. If you’ve ever peeked behind your doctor’s reception desk at the wall of paper files, you know how much information is kept on patients. Which bring us to the second major hurdle: With all that information digitized for digital doctor visits, just how safe will it be? Federal HIPAA laws create high standards for record-keeping, but can HIPAA regulations anticipate the legal and technical loopholes that digital medicine will almost certainly create?

10 STEPS TO RENAL HEALTH

10 STEPS TO RENAL HEALTH “If you have high blood pressure, diabetes, a family history of kidney failure, or are over age 60, the best thing you can do is to get tested for kidney disease annually by a doctor,” Sean Roach, Public Relations Manager for the National Kidney Foundation tells EDGE. “Usually, a urine test is all you need.”

“If you have high blood pressure, diabetes, a family history of kidney failure, or are over age 60, the best thing you can do is to get tested for kidney disease annually by a doctor,” Sean Roach, Public Relations Manager for the National Kidney Foundation tells EDGE. “Usually, a urine test is all you need.” Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is found in 26 million adults in the United States. The most common causes of CKD are diabetes and hypertension. Data shows that African Americans and Hispanics are disproportionately effected.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is found in 26 million adults in the United States. The most common causes of CKD are diabetes and hypertension. Data shows that African Americans and Hispanics are disproportionately effected.

OLD SCHOOL

OLD SCHOOL