In league with an extraordinary gentleman

Photography by Daryl Stone

Prologue

It is the winter of 2006. At a lively (read: heated) meeting of the James Beard Restaurant and Chef Awards Committee, Alan Richman punctuates discussion with zippity-quick one-liners that smack of truth as they provoke laughter. A gavel invariably pounds on the conference room table, demanding order. At one point, Pete Wells, now the restaurant critic for The New York Times, leans over, nods at Richman and whispers to me, “Someone should follow him around with a tape-recorder.”

Eight-and-a-half years later, I finally take that excellent advice. I do so in Alan Richman’s hometown of Somerville, where the most decorated food writer in America’s history was born.

Present

Alan Richman, restaurant critic for GQ magazine, dean of food journalism and new media at the International Culinary Center in New York, author of the acclaimed book Fork It Over as well as thousands of newspaper and magazine articles, and recipient of the Bronze Star in the Vietnam War, is having lunch at Martino’s Cuban Restaurant on West Main Street in Somerville. It is a hot summer day.

Alan Richman, restaurant critic for GQ magazine, dean of food journalism and new media at the International Culinary Center in New York, author of the acclaimed book Fork It Over as well as thousands of newspaper and magazine articles, and recipient of the Bronze Star in the Vietnam War, is having lunch at Martino’s Cuban Restaurant on West Main Street in Somerville. It is a hot summer day.

“Is this the $4 salad?” Richman asks. “It’d be $40 in New York.”

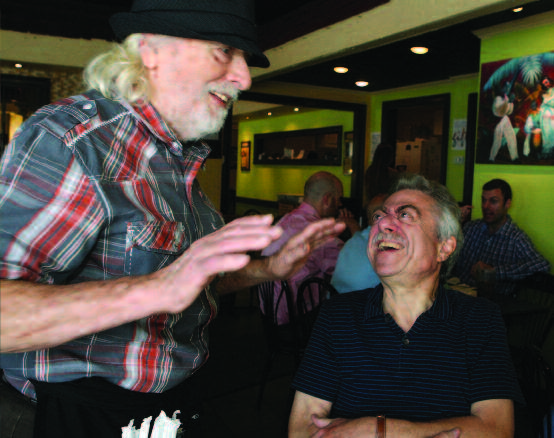

As he dissects the ingredients, chef-owner Martino Linares (above) comes over to the table to listen in. He personally took, and approved, our order.

“The (iced) tea is nicely composed,” Richman adds. “The lemon is already in it. It usually takes me 15 minutes to get the lemon right.”

Linares beams. “Good, heh?” he says.

“All of this might be as good as you say it is,” Richman replies, waving his arm around the food-laden table. Linares chuckles and hops off to sing “Happy Birthday” at another table.

The incognito restaurant critic continues.

“The two things I’ve always hated are empanadas and tamales. Empanadas are always grotesquely soft. But this one is great. It’s delicate. It’s also crunchy. Look at the crimping around the edges. The sauce is smoky.”

And then: “This tamale, the pork, is really good. You know, the Cubans in Cuba have forgotten how to cook. This is good cooking.”

Linares, birthday song sung, is back for more Richman, and he gets what he wants. “My girlfriend and I were looking for a place to celebrate her birthday. I’ll take her here.”

Alan Richman, 70, recalls flying to Cuba from Miami in a pre-Castro time and “eating coconut ice cream out of a coconut shell.”

“Ah! The best!” Linares, 86 going on 16, exclaims in approval.

“When I was a little boy,” Richman tells Linares, “we’d go to Miami Beach. I always wanted to stay in the Fontainebleau Hotel.”

“I cooked there,” Linares says. He’d first come to the States in 1950, volunteered for the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, was captured and spent three years in a Cuban prison. After his release, Linares returned to Miami—and cooked at the Fontainebleau. Thus began his career cooking in big-city French and Italian restaurants in America.

The Cubano arrives, sliced and served jelly roll-style on a platter.

“This is like a Cuban hoagie,” Richman says. “Real roast pork! Look at this thing!

“You know what?” says the man who has won 16 James Beard Awards for his writing on restaurants and food. “I think this is the best restaurant in America.”

Martino Linares does a cross between a jig and a tango as Richman examines the sandwich’s layers.

“This Cubano needs a few more pickles.”

Past-Life Experiences

Richman was born in Somerville in 1944. Though his family moved north to Hillside when he was 5, then subsequently to the Philadelphia suburbs, his grandparents as well as other relatives remained in Somerville. The Richmans visited regularly, which may explain the food critic’s vivid memories of “a wall of comic books in a gas station” near his childhood home on Codington Place.

“It was the Mount Rushmore of comic books. I’d sit there for hours.”

His grandparents, Rose and Nathan Rabinowitz, belonged to the Orthodox temple in Somerville, where young Richman “sat through services in 107-degree heat.” Though his grandmother “wasn’t a very good cook,” she did make a “fine kuchin.”

His grandparents, Rose and Nathan Rabinowitz, belonged to the Orthodox temple in Somerville, where young Richman “sat through services in 107-degree heat.” Though his grandmother “wasn’t a very good cook,” she did make a “fine kuchin.”

At the time, however, Richman fixated on hot dogs and a certain gumball machine that spat forth, if you were lucky, “rainbow-colored gum. Or something like that.” Richman-the-boy “wanted that rainbow gum because, with that, you also got a candy bar.”

From his home base on Codington Place, Richman would go with his grandmother to the old Cort Theatre (“I saw the most boring movie there—The Quiet Man”) but avoid the Hotel Somerset, whose sign still reigns over part of downtown Somerville. “It gave me the creeps.”

Somerville residents never avoided Raymar’s Center, owned and operated by Richman’s Uncle Sidney until 1976. Now it’s called Redelico’s; owner Randy Redelico worked for Raymar’s. He says that Sidney Raymar taught him “everything I know about paint and decorating.”

While Raymar’s was at its peak, brightening homes in blossoming Somerset County, Alan Richman was a student at the University of Pennsylvania (“Candice Bergen was in my class”). After college, Richman joined the Army and, in 1966, was in the Invasion of the Dominican Republic. In 1969, he was called to service in the Vietnam War.

“I was in the world’s largest Army boat company. I used to ride on the Saigon and Dong Nai Rivers, the Mekong Delta.” He claims he “didn’t do anything brave,” though he rose to the rank of captain and was awarded the Bronze Star.

“I loved Vietnam,” he says.

Newspapers were his next stop. Richman became a sports writer (Philadelphia Bulletin), then a sports columnist (Montreal Star, Boston Globe). It was at the Globe that Richman pioneered long-form writing about sports. Sports writers tend to travel to cities where games are played, so Richman started eating in various restaurants in various locales.

By the time he was on staff at The New York Times, he was working on major-league national news stories. “I covered Three Mile Island. I covered the disappearance of Etan Patz.”

Then he went to People magazine, where he was “the first person hired to report and write their own stories,” not merely a hack fashioning an item out of dispatches from correspondents.

“I did a cover story on Oprah Winfrey. I sat in Grace Jones’s living room as she was having a breakup with Dolph Lundgren. I covered the comeback of Vladimir Horowitz in Paris. There was so much money then,” which meant Richman dined well wherever he traveled.

By this time, he was writing about things culinary as a hobby and doing a regular wine column for Esquire magazine. After five years at People, he moved onto GQ.

It wasn’t long before his singular voice in food-writing drew national acclaim.

In 1991, Richman won the very first James Beard Award for food writing. His name has been called out 15 additional times at ceremonies dubbed the “Food Oscars.” There have been numerous additional honors, ranging from citations from the International Association of Culinary Professionals to a National Magazine Award.

His unique combination of wit and wisdom has dominated the culinary world for more than a quarter-century.

Epilogue

Alan Richman doesn’t have a cell phone. Well, he sort of has a cell phone, but it’s “one of those throw-away phones drug dealers use.” He can call you, but you can’t call him, in other words.

He’s explaining this as we take a break from looking for the spot that possibly could’ve been the circa-late-1940s/early ‘50s gas station with the wall of comic books. We’re in another Somerville restaurant, though Richman finds this one as offensive as the cell phone.

“The purpose of cell phones is so people can incon-venience those they are planning to meet,” he says.

Pete Wells was very right.

FOR FUTURE REFERENCE

FOR FUTURE REFERENCE

Alan Richman’s work can be seen in GQ, both the print edition and on the web site. For information about his classes at the International Culinary Center in New York, visit internationalculinarycenter.com.

Fork It Over, published in 2004 by HarperCollins, showcases the writer’s range. It’s a little bit memoir, with a whole lot of vintage Richman commentary.

When in Somerville, stop in for lunch or dinner at Martino’s Cuban, 212 West Main Street; 908-722-8602; martinoscuba.com.