“I am definitely stealing that pancetta vinaigrette for a dozen different dishes I cook at home.”

Ursino’s executive chef, Peter Turso

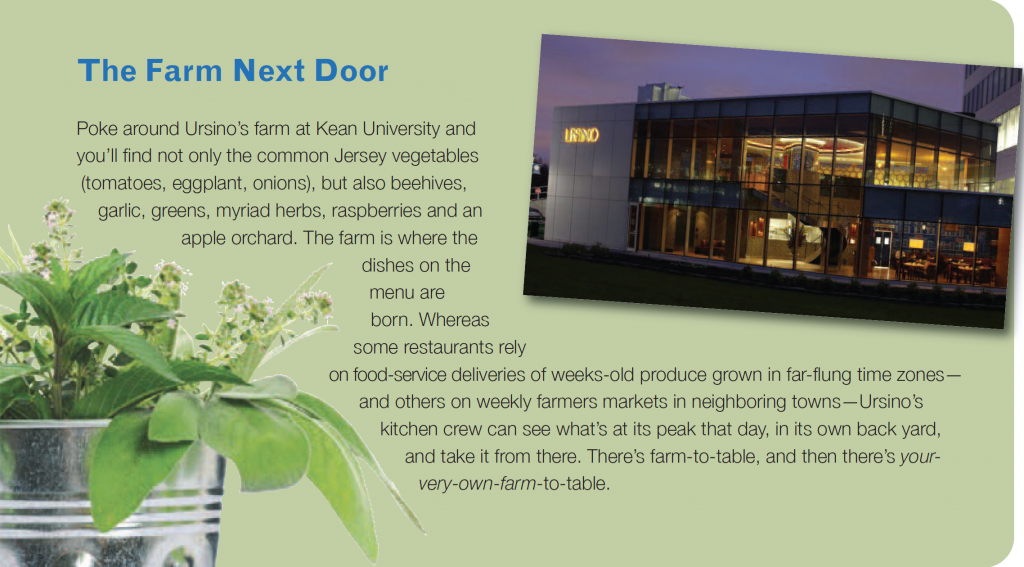

Back there,” my friend said, pointing to his left as we walked across an expansive parking lot at Kean University to Ursino, a restaurant set in a science building amid classrooms and common spaces. “That’s where the farm is. Four acres. You don’t expect it, but it’s there.” He continued to describe the produce he saw growing during a summertime tour—how the farm was laid out, and the enthusiasm for the percolating crops displayed by Ursino’s executive chef, Peter Turso, and the farmer-in-residence, Henry Dreyer. Four lush, green acres are cloistered in crammed-full Union that are mined to the max by the farm-to-table team of Turso and Dreyer. As he detailed the operation, I envisioned similar campus farms sprouting at any one of New Jersey’s institutions of higher learning. I’m glad for the overview my friend provided because, once inside Ursino’s thoroughly modern, multilevel dining areas, that was the only mention of the mere-yards-away, oncampus farm I heard. Not one member of the service staff took a moment to tell us of the unique relationship between Kean and Ursino, the reasons for its existence and how  Turso’s menu reflects what’s grown by Dreyer and his farm crew. The menu descriptions, while referring to the origins of ingredients such as Barnegat scallops and “local” oysters, all but ignored this extraordinary plus. For instance, Liberty Hall beet salad, with its richly colored baby carrots, nibs of honeyed walnuts and sparks of sharp Valley Shepherd cheese, was a rousing harbinger of autumn on this latesummer night. Yet nowhere is it explained that Liberty Hall is both the name of one of Kean’s campuses and a history museum, originally the elegant home of New Jersey’s first governor. (You’d think an education would be part of the dining package.) We had to ask about almost everything, and waits between questions and answers often were long. On the other hand, Turso’s focused, uncomplicated food doesn’t need a promotional boost. Slice into the smoked swordfish, smartly partnered with shavings of crunchy fennel and perky pea tendrils, and you’ll quickly be distracted from service flaws by flavor rhythms of the rich fish as it intersects with a smack of anise from the fennel and the engaging rawness of the shoots.

Turso’s menu reflects what’s grown by Dreyer and his farm crew. The menu descriptions, while referring to the origins of ingredients such as Barnegat scallops and “local” oysters, all but ignored this extraordinary plus. For instance, Liberty Hall beet salad, with its richly colored baby carrots, nibs of honeyed walnuts and sparks of sharp Valley Shepherd cheese, was a rousing harbinger of autumn on this latesummer night. Yet nowhere is it explained that Liberty Hall is both the name of one of Kean’s campuses and a history museum, originally the elegant home of New Jersey’s first governor. (You’d think an education would be part of the dining package.) We had to ask about almost everything, and waits between questions and answers often were long. On the other hand, Turso’s focused, uncomplicated food doesn’t need a promotional boost. Slice into the smoked swordfish, smartly partnered with shavings of crunchy fennel and perky pea tendrils, and you’ll quickly be distracted from service flaws by flavor rhythms of the rich fish as it intersects with a smack of anise from the fennel and the engaging rawness of the shoots.

With the grilled octopus, also a starter, a taut, charred crust yields to a softer center as harmonious riffs of accents enhance the fundamentally bland but meaty sea creature. There’s the silky puree of Marcona almonds, the sweetness of roasted red peppers and the spirited heat of chimichurri. All prod more from the octopus than typical treatments with lemon and garlic. We asked for spoons to help us get all we could out of the coconut-curry mussel pot. It’s a bountiful cauldron of large mussels in a rousing sauce that resonates with curry’s warming mix of spices tempered by the cooling sweetness of coconut milk. A bonus on the side: crunchy, spunky, slightly salty shrimp toast, the perfect sop-up agent. During the waits for wine and food, my dining companion offered the background the staff didn’t—on Turso (experienced chef, stints at Nicholas in Middletown and David Drake, now shuttered, in Rahway) and Dreyer (veteran farmer, renowned and beloved in the region), and why Kean U. wanted both a farm and an upscale restaurant (farm-to-table is on-trend and attractive to potential students, their parents, alumni and donors). In my mind, I added an introduction to the menu that said, “Your vegetables are grown on this campus. Please take a short walk and visit our farm.”

Those Barnegat scallops do have a ball, tossing tastes back and forth with Dreyer’s roly-poly turnips and bitter, but braised-to-sweet radicchio. As I swiped a scallop speared with a slice of turnip, a leaf of radicchio and a sliver of sweet apple through a wash of citrus-licked butter sauce, I tasted exactly why this farm-to-table thing has taken root: Fresher is better. But I did want to know where the “local pork” and its hen-of-the-woods mushrooms that star in one of Turso’s signature dishes come from. So even if the captains don’t care to connect, a little menu rewriting could serve as a bridge. Ursino’s expertly cooked, top-quality halibut has no problems connecting to an accompanying stew of leeks, red onions, fennel and potatoes. Uniting it all is a vivacious vinaigrette, punctuated by smoky-sweet pancetta that underscore for me why dining out and experiencing strong new voices in food is a joy. I am definitely stealing that pancetta vinaigrette for a dozen different dishes I cook at home. Terrific, and then some. Less than terrific was the cheese plate. I’d asked if any of the cheeses were from the revered Valley Shepherd, of Long Valley, and was told “maybe one,” without specifics, by a plate runner. He returned to say “all the cheeses” were Valley Shepherd’s, though still without much in the way of details. We gambled, and though my favorite nettle-streaked cheese made it to the plate, we were served just six paper-thin, inchlong slivers of cheese that looked lonely and wan on the large plate. And for $15. No price-to-portion quibble with the lemon ricotta ice cream sandwich, with almond sponge cake forming the bookends and raspberry, lavender and teensy sprigs of basil reminding us of that very nearby farm. I wasn’t impressed, though, by the heavy-textured banana bread pudding, laden as it was with too many layers of caramel, chocolate and hazelnut. As we walked out of Ursino and back across the parking lot, my friend says, “Food’s great here, but how would you know there’s a farm behind it? Shouldn’t that be all over the menu and the first thing the servers say?” Yes to both.

Ursino, as envisioned by its chef and its farmer, hits the mark with fresh-faced food that routinely tips its hat to its origins through inherent simplicity. It follows Rule No. 1 in cooking—don’t mess too much with fine ingredients—to the letter. But it’s incongruous, particularly in a university setting, that the educational component of farm-to-table is lacking. But this is an easy fix; basic menu-editing and staff instruction. By the time you read this, the team of chef Peter Turso and farmer Henry Dreyer will almost certainly have aced the test.

Editor’s Note: Andy Clurfeld has been an advocate of “buying local” in the Garden State since the late 1970s, so the burgeoning farm-to-table movement is hardly new to her. She writes the syndicated food-wine pairing column Match Point and has been covering everything New Jersey—from politics to crime to tax issues (and of course food!)—as a newspaper and magazine journalist for more than three decades. She was a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2010.