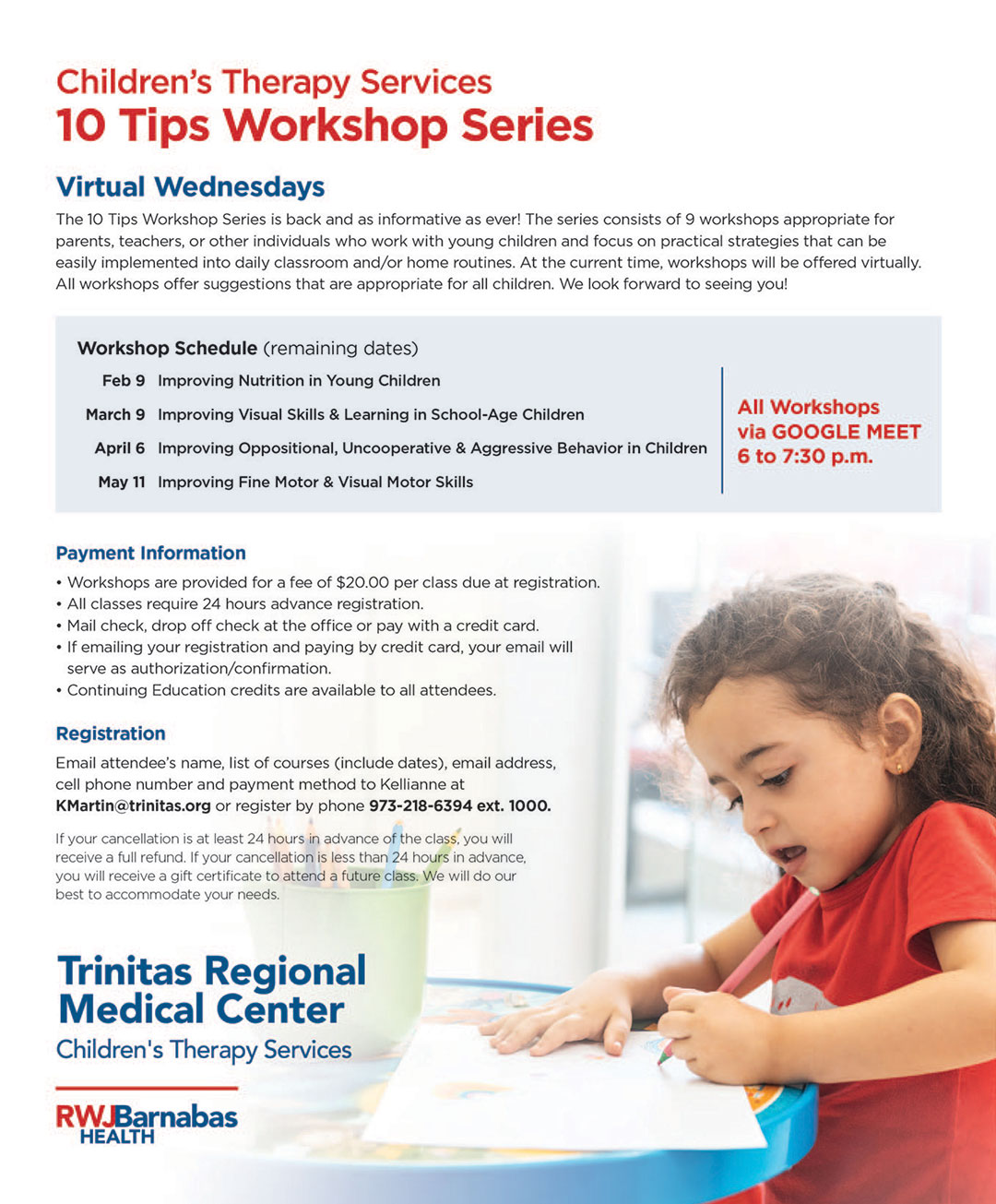

That year Elizabeth played baseball with the big guys.

Karen Finkelstein

During the winter of 1872–73, Elizabeth caught an expensive case of baseball fever. The sport had long been popular in the city, which had grown to over 20,000 residents in the years after the Civil War. In 1870 and again in 1872, Elizabeth’s amateur baseball club, the Resolutes, had claimed the New Jersey championship. Their main rivals were in Jersey City, Newark and Irvington. The 1872 championship, the result of a 42–9 thumping of the Champion Club of Jersey City—along with rousing victories over some leading professional clubs—convinced supporters of the Resolutes to recruit a lineup of professional players in 1873 and join the National Association, forerunner of today’s National League. This would mark the city’s one and only season in baseball’s big leagues. Their competitors that year included teams from major cities: Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Brooklyn, and Washington, DC.

As insane as it seems to see Elizabeth on that list of “major-league” cities, the enthusiasm heading into the spring of 1873 was not entirely unfounded. Most experts considered the 1872 Resolutes the finest amateur team in the region, if not the nation. But baseball was still a very young sport and few teams had found a way to make the professional game profitable. Even the Boston Red Stockings, the National Association’s pennant-winners in 1872, were thousands of dollars in debt at the end of the year and sent some of their players home for the winter minus a final paycheck. The Resolutes hoped to solve this problem by forming a “cooperative” club. They would pay their expenses and salaries from their portion of each game’s gate receipts, collected from the city’s rabid baseball populace.

NJSports.com

This was a fine idea on paper, but if you were a top player in 1873, would you play for a club that couldn’t guarantee your salary? If you said No way then you’re not alone. The Resolutes were laughed off by nearly every player they approached with this scheme. With no top stars interested in this proposition, the Resolutes cobbled together a roster of players from previous failed cooperative experiments, along with some local journeymen and a few better players who, unfortunately, were known as much for their surly attitudes and fondness for the bottle as their skills on the diamond. Those who did throw in with the club were encouraged by the fact that the team’s catcher, Doug Allison (above), was also the manager. The 26-year-old was the closest thing the Resolutes had to a “star.”

Catcher was the most important position on the field in the 1870s and Allison was one of the first players to move right up behind the batter to receive pitches on a fly instead of on a bounce, inviting the bat to cut through the air just a few inches from his face. A bit like NASCAR fans, Allison’s supporters came to witness his skill and daring, while also recognizing that a bloody accident was potentially just one pitch away. Another notable Resolute was a scary guy named Rynie Wolters, the first professional baseball player born in the Netherlands. Wolters had made a living in the 1860s as a cricket bowler and took up baseball pitching as the fortunes of the latter rose and the former faded. Despite the fact they served as Elizabeth’s opening day battery, Allison and Wolters were not what you’d call team players. They were baseball mercenaries and made no bones about it.

Filling out the lineup were Doug Allison’s brother, Art, along with Eddie Booth and Henry Austin—who formed the Resolute outfield—pitcher Hugh Campbell, and Favel Wordsworth, a shortstop with a name that seemed more appropriate for the stage than the diamond.

More than 500 fans braved chilly late-April temperatures to watch the Resolutes play their first official game, in Philadelphia. Wolters was horrible and they lost to their hosts, the Athletics, 23–5. Wolters stormed off and did not pitch again for Elizabeth, leaving Campbell to shoulder almost the entire pitching load the rest of the year. The Resolutes made a better showing in their second contest, falling to the Baltimore Canaries by an 8–3 margin, this time in front of 300 spectators.

Karen Finkelstein

Three areas of concern that cropped up almost immediately were that 1) the players didn’t seem to be gathering for practice between games, 2) because their home field did not have a dressing room, the player had to change into their uniforms in an Elizabeth rooming house, and 3) for some reason lost to history, the club was not actively advertising the date and location of its games.

Elizabeth was winless in May and, despite logging its first victory—over the Brooklyn Atlantics and their star fielder Bob “Death to Flying Things” Ferguson—barely drew flies for the club’s June meeting with the star-studded Red Stockings. Low attendance not only reduced the Resolutes’ basic operating capital, it also ate into the players’ “co-op” income, the combination of which triggered a slow, agonizing death spiral.

When the Resolutes visited Boston in July, the Red Stockings crunched two games into one day, marking what appears to have been professional baseball’s first doubleheader. The first of those games turned out to be the National Association’s greatest upset, an inexplicable 13–2 win by Elizabeth. The Red Stockings, with four future Hall of Famers in the lineup, woke up and won the second game, 32–3. The great victory in Boston was only the Resolutes’ second of the year and, as it turned out, their last of the season. They finished 2–21 in official league games and folded as a professional organization in August after several key players abandoned ship in search of better paydays.

Though an unqualified failure both on and off the field, the Elizabeth Resolutes were nonetheless a noble attempt to elevate a growing but still-small city to big-city status through sports. It wasn’t the first time civically minded American citizens tried to pull this off, nor would it be the last. The difficulties encountered by the club did, however, bring most sane baseball people to the painful conclusion that cooperative teams could not and should not be a part of the growing professional game. The numbers simply did not work. The good news is that the Resolutes reverted to amateur status and remained one of the state’s better teams for several years.

Elizabeth never lost its appetite for baseball. Its sandlot and high school teams produced more than two dozen professional players over the years—most recently Alex Reyes of the St. Louis Cardinals, who pitched in the 2021 All-Star Game. As for the Resolutes, well, they are still playing—their home field is actually in Rahway River Park—as a vintage baseball club that uses the same rules and equipment the original Resolutes did in the 1870s. The team was conceived by the late Paul Salomone of Westfield and first took the field in 2000.

Editor’s Note: For more information on the Elizabeth Resolutes vintage baseball club, visit their Facebook page.