The Energy Star program turns 25.

By Caleb MacLean

As 25th anniversaries go, the milestone celebrated by the EPA and DOE for its Energy Star program in 2017 doesn’t rate particularly high on the thrill meter. The same year the program was launched (1992), Cartoon Network went on the air, the Mall of America opened in Minnesota, John Gotti was sentenced to life in prison, and Vice President Dan Quayle gave his famous Murphy Brown speech. No one cracked out the champagne for any of those events either. And yet, all these years later, we encounter Energy Star stickers almost every time we enter a store (brick and mortar, as well as online) that sells computers, TVs and appliances.

Which got me wondering…what the heck is Energy Star and do I even know what that rating means?

Like 88 percent of Americans, I am aware of the Energy Star “brand” and can bluff my way through a fairly good explanation of why it’s important. But just for the record, the Energy Star program was created by our federal government—jointly by the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Energy—during the Bush I administration. Initially, it was aimed at the power-sucking computer industry, as more and more Americans were purchasing desktops in their homes. The Internet was barely a thing back then; one wonders whether the Energy Star architects saw it coming.

Like 88 percent of Americans, I am aware of the Energy Star “brand” and can bluff my way through a fairly good explanation of why it’s important. But just for the record, the Energy Star program was created by our federal government—jointly by the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Energy—during the Bush I administration. Initially, it was aimed at the power-sucking computer industry, as more and more Americans were purchasing desktops in their homes. The Internet was barely a thing back then; one wonders whether the Energy Star architects saw it coming.

The chief architect, in case you were wondering, was John Hoffman, one of the first federal officials to seriously study climate change. In the 1980s, he convinced Ronald Reagan to back an international effort to protect the ozone layer. Hoffman then moved on to conceiving Energy Star, which was his clever way of reducing power plant emissions that produce greenhouse gases, without actually going after the power plants. Hoffman got the idea while looking around his Washington office at all the humming CPUs and monitors, and wondering if there was some way for manufacturers to create a “sleep” or “low-energy” mode. The program, which was voluntary, soon spread beyond computing to other appliances, and was implemented during the Clinton administration by Brian Johnson and Cathy Zoi, who guided the president’s energy policy

Today, the Energy Star program saves tens of billions of dollars a year in energy, and has been adopted by the European Union, Canada, Australia, Japan and several other first-world countries. To earn an Energy Star designation, a product must demonstrate that it uses at least 20 percent less energy than required by standards set by the EPA or DOE. That number depends on the product. A dishwasher must prove a 41 percent savings. Fluorescent lights must use 75 percent less energy and last 10 times longer than a standard-issue light bulb. TV’s have to come in at 30 percent. Newly constructed homes can also qualify for an Energy Star rating; they must use 15% less energy than homes built in 2003. In all, more than 50,000 different products are now part of the program. About half of American households purchase at least one Energy Star–rated product a year.

Today, the Energy Star program saves tens of billions of dollars a year in energy, and has been adopted by the European Union, Canada, Australia, Japan and several other first-world countries. To earn an Energy Star designation, a product must demonstrate that it uses at least 20 percent less energy than required by standards set by the EPA or DOE. That number depends on the product. A dishwasher must prove a 41 percent savings. Fluorescent lights must use 75 percent less energy and last 10 times longer than a standard-issue light bulb. TV’s have to come in at 30 percent. Newly constructed homes can also qualify for an Energy Star rating; they must use 15% less energy than homes built in 2003. In all, more than 50,000 different products are now part of the program. About half of American households purchase at least one Energy Star–rated product a year.

Of course, there were some bumps and bruises along the way. Many companies found loopholes enabling them to qualify inefficient products for the Energy Star program. Between 2006 and 2011, critics pointed out other major flaws, including the fact that some companies were allowed to test their own products, and then submit the results. You can imagine how that worked out. In 2011, the EPA slammed the lid on this type of fraud by demanding that all products sold in the U.S. be tested and certified by an EPA-recognized third-party laboratory. Part of the EPA budget cuts proposed by the Trump Administration in 2017 would reportedly eliminate this safeguard, so stay tuned.

Another criticism leveled at the program is that, for certain appliances, a sexy Energy Star rating may have a downside. For instance, an energy-efficient fridge may use a smaller compressor, have more insulation and employ a computer to regulate temperature. That either means less room inside or more space taken up outside (because of added insulation), and also that a buyer might have to service or replace a compressor or computer that fails. If that fridge turns out to be too much of a headache, it will end up in a landfill long before its intended lifespan, where it could damage the environment.

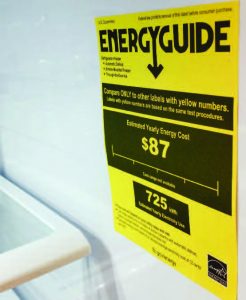

For now, at least, those bright yellow tags do mean something. That’s important to understand because, generally speaking, the better the performance, the more expensive the purchase price will be. The idea is that, over time, the products with the highest ratings will actually be “cheaper” thanks to lower energy costs.

For now, at least, those bright yellow tags do mean something. That’s important to understand because, generally speaking, the better the performance, the more expensive the purchase price will be. The idea is that, over time, the products with the highest ratings will actually be “cheaper” thanks to lower energy costs.

The first thing to look for when shopping is the Energy Star logo, which is usually located in a corner of the label. Next, under the words Energy Guide (where the bottom of the Y is an arrow), you’ll find a dollar amount. That represents a rough estimate of what the appliance will cost to run over a year. Under the dollar amount is a number that represents the kilowatt hours of electricity the appliance is likely to consume. Both numbers are handy for doing side-by-side comparisons. If you have an electric bill handy, you can actually multiply the cost per KwH listed on your statement by this number and see if it will cost more or less to run in your area.

www.istockphoto.com

The administrators of the Energy Star program will be the first to admit that its numbers are only a guideline. Also, they are far more impactful in some categories than in others. And as technology changes so do the program’s standards. The numbers of the past quarter-century, however, definitely speak for themselves. Buying and building within the Energy Star spectrum has saved the world a half-trillion dollars in energy costs…and helped us all breathe a bit easier.

Editor’s Note: Many Energy Star appliances pay off with tax credits, too. Typically these credits can be applied to your state tax bill, not your federal return. To better understand how rebates work, visit energystar.gov and type in your zip code.