Easing the Stigma of Mental Illness and Addiction

By Yolanda Navarra Fleming

If anyone can speak with authentic candor to a ballroom full of people about behavioral health and addiction, and make them simultaneously laugh out loud and nod in empathy, it’s Patrick J. Kennedy II, the former U.S. Congressman, mental health advocate and author of the New York Times Bestselling book titled A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction (Blue Rider Press, New York, 2016).

If anyone can speak with authentic candor to a ballroom full of people about behavioral health and addiction, and make them simultaneously laugh out loud and nod in empathy, it’s Patrick J. Kennedy II, the former U.S. Congressman, mental health advocate and author of the New York Times Bestselling book titled A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction (Blue Rider Press, New York, 2016).

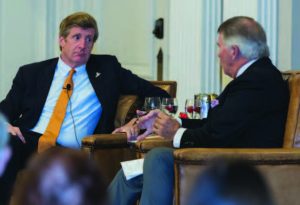

In October 2018, the Trinitas Health Foundation launched their Peace of Mind Campaign with an informative evening with Journalist Jack Ford moderating a conversation with Kennedy on “Easing the Stigma about Behavioral Health” at The Park Savoy Estate, Florham Park.

In October 2018, the Trinitas Health Foundation launched their Peace of Mind Campaign with an informative evening with Journalist Jack Ford moderating a conversation with Kennedy on “Easing the Stigma about Behavioral Health” at The Park Savoy Estate, Florham Park.

The event raised $235,000 toward the $4 million renovation project to update Trinitas’ Behavioral Health facility, one of the most comprehensive departments of behavioral health and psychiatry in New Jersey. They offer specialized services for adults, children and their families, as well as services for those with various addictions, and a 98-bed inpatient facility. The hospital welcomes nearly 200,000 behavioral health visits per year. The multi-disciplinary and bi-lingual staff includes psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, nurses, creative arts therapists, substance abuse counselors and mental health workers, offering such services as psychiatric, emergency response/screening center, inpatient, outpatient, partial hospital programs and addiction services.

The event raised $235,000 toward the $4 million renovation project to update Trinitas’ Behavioral Health facility, one of the most comprehensive departments of behavioral health and psychiatry in New Jersey. They offer specialized services for adults, children and their families, as well as services for those with various addictions, and a 98-bed inpatient facility. The hospital welcomes nearly 200,000 behavioral health visits per year. The multi-disciplinary and bi-lingual staff includes psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, nurses, creative arts therapists, substance abuse counselors and mental health workers, offering such services as psychiatric, emergency response/screening center, inpatient, outpatient, partial hospital programs and addiction services.

Trinitas provides treatment for patients like Kennedy, who was diagnosed with asthma as a child, and went on to suffer through a lifetime of depression, bipolar disorder and substance use, which included many failed attempts at sobriety until he arrived at the right balance of medication and alternative therapies.

Patrick Kennedy, son of the late Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy and Joan Kennedy, has fully embraced his DNA. He has worked tirelessly to shed new light on the struggle with mental illness and addiction that hang—now in plain view—on numerous branches of his family tree. In true Kennedy fashion, he is in the public eye working to right certain wrongs, more specifically, to get the world on board with the fact that the brain is part of the body and requires (and deserves) proper medical attention just like any other part. But unlike the Kennedys before him, he practices a sort of transparency that he recognizes as his destiny, which he fully owns both in spite of his DNA and because of it. In his book, he admits to the mistakes he has been hardwired to make and since then, has made easing the stigma of behavioral health his sole mission.

His passion was contagious when he and journalist Jack Ford discussed Patrick’s position as the nation’s leading political voice on mental illness, addiction, and other brain diseases. Ford’s focus on the subject stems from the fact that his father died from alcoholism at age 49.

Kennedy’s efforts to create stronger advocacy for all types of mental health and substance use disorders, have manifested in, among other things, lead sponsorship of the Mental Health Parity and Addictions Equity Act of 2008, as well as the creation of two nonprofit organizations—The Kennedy Forum and One Mind, which aim to provide and encourage groups that would normally compete for research dollars and support in other forms, to join forces.

The Kennedy Forum leads a national dialogue on transforming mental health and addiction care delivery by uniting mental health advocates, business leaders, and government agencies around a common set of principles. One Mind pushes for greater global investment in brain research, which Kennedy has called “the next great frontier in medicine,” and is pioneering a worldwide approach to make scientific research, results, and data available to researchers everywhere.

Progress has been made, but Kennedy says there is much more that can be done to encourage acceptance that brain illnesses should be treated with the same level of concern and respect as other diseases of the body such diabetes, cancer, heart disease, etc.

Here is a large portion of their conversation.

Jack Ford: You have clearly become one of the champions in the area of mental health and addiction. …You have been very open and candid in your book talking about your own life and your own struggles. There has always been a spotlight on the Kennedy family, and it’s something you cannot run and hide from. But what made you decide to step into that spotlight to talk about this in your own personal journey?

Patrick Kennedy: …I didn’t ask to be here as the advocate for mental health and addiction. I never wanted to be here at a podium being asked about this part of my life… and living in a family that also suffered from mental health and addiction. You got me by default. I became the leader of mental health and addiction policy in this country because I put my name on a bill that said the brain was part of the body. I never expected to be the first name on the bill. I thought because in my father’s case it took him 50 years in the US Senate before he got sponsored whatever he wanted because he was in the Senate longer than almost anyone else and he was chair of the big committees. So it was odd that as the youngest member of Congress, at 27, from the smallest state in the country and in the minority party, and as the lowest guy on the totem pole I got the chance to put my name number one. I got to be the sponsor. How in the world does that happen? Because no one else wanted to have to go in front of the cameras and have Jack ask them the same question he just asked me. That is the honest-to-God truth. No politician wanted to get up there and say they’re a champion of mental health, knowing that all of us are affected by it, and then have a press person ask about our own family situations. Because if we said anything, well, that yarn just spools right out and where do you reign it back in? And so you’re in trouble. If you say you’ve never been to treatment yourself, then you’re a one-termer. You say it’s happened to anyone in your family and you’re in the dog house with them, and you might be affecting their mental health by outing them involuntarily. So, there is no good minefield to walk through on this. And if you say no, they’ll think you’re a liar. So that’s why no one else wanted to put their name first.

I put my name first, not because…I keep reminding my Republican colleague Jim Ramstad, who I co-sponsored this with, he goes…if your uncle were alive he’d put you in a chapter in his book Profiles in Courage, but I have to tell everyone…the only reason I came out was because the guy I was in drug treatment with sold his story about being in drug treatment with me to the National Inquirer, which meant my face was on the cover (with the headline), “Patrick Kennedy: Cocaine Addict.” When I got up one morning, I was a second-term member of the State Legislature, and that was on every check-out counter in my district. I thought I was all done, as you would expect. I represented a very conservative neighborhood in Providence, RI, in the State House. The good thing is that my neighborhood was predominately Italian-American. Even though no one liked a drug addict, they really didn’t like someone who ratted on a drug addict. My posse…we started a re-election bid on “We’re not for the Rat Bastards; we’re for Patrick Kennedy.” That was my campaign slogan.

JF: That sounds like a skit from Saturday Night Live.

PK: Life is often like that.

JF: You’re right. So you became the lead sponsor with a bi-partisan backing, signed into law in 2008 by President George W. Bush. The title of the act is the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. Why did you feel there was a need for the Federal Government to pass this act and what were you hoping it would provide?

Jill Sawers, Campaign Co-Chair & Trinitas Health Foundation Trustee Chair

PK: I was incredibly blessed because everything I was exposed to in life kind of set me up for this. If I look back on my life now, I could never have orchestrated the way it turned out, in a better way for me. My Aunt Eunice started Special Olympics with my grandmother. My family was steeped especially in the Disability Rights Movement, my father worked on the Americans with Disabilities Act. I was very sensitized to people who were treated as “the other,” particularly if they had a brain illness of some kind. My Aunt Rosemary, frankly, had a lobotomy because of her psychiatric disorder. Most people don’t know that. She had a mild form of intellectual disability. And yet, like many people, a certain percentage of those with intellectual disability also have psychiatric disorders. Everything I’ve read and learned about my Aunt Rosemary, leads me to conclude she had a psychiatric disorder, which really unnerved my grandfather, as it would any parent. At that time, lobotomy was the standard form of therapy. When that didn’t go well, she was banished from my family, and was sent to Wisconsin and wasn’t seen again by any member of my family, until after my grandfather had a stroke. My grandfather never saw her again after the lobotomy. That shame was so deep in my family that it transmitted itself through my father’s generation. When I think about my father’s inability to address what’s right in front of him, …he had learned and become very good at denial. It allowed him to survive things that…no one could survive what my father survived.

Deborah Q. Belfatto, Campaign Co-Chair & Trinitas Health Foundation Trustee

I was sensitized to that and to growing up with my mother being vilified because of her alcoholism. She would walk through the house inebriated in the middle of the day. My dad would have all of our nation’s leaders come to our house, people you would recognize and know of, and none of them would look up when my mother walked through the hallway. As a kid, I totally got the message to get her back in the room and shut the door. My brother, sister and I spent our childhoods doing all we could to hide our mother so she wouldn’t embarrass anybody. That was on family vacations, in our house and everywhere we went. I never got to connect with my mother on an emotional level because she was so debilitated by her illnesses, both alcoholism and severe depression, but I felt the need to defend her. Throughout my life, that’s what I took on.

I really feel blessed that I was able to support this bill and that, ironically, the House version of the bill covered alcoholism and depression and the Senate version of the bill did not. I could not get any agreement between the House and the Senate versions. But when my dad got brain cancer and he was home and nearing the end of his life, I asked him to help get the House version passed. He told me to call Chris Dodd, his best friend. …four days later, the market collapsed and the banks in this country went belly-up, and all of a sudden, Chris Dodd became somebody. He was Chairman of the Banking Committee and all of a sudden he was the most important man in Washington, D.C. That was four days after I asked for his help to get HR1424, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act passed.

He called me back and said, “Patrick, we have to pass this bail-out of our nation’s banks. It’s going to cost the taxpayers between $700 and 800 billion dollars. None of us wants to vote for it, but we know if we don’t, our country could end up in another Great Depression. That was the feeling on Wall Street and around the country at that time. He said, “I have an idea.” I said, “What’s that?” He said, “How about I write the whole Toxic Acid relief program into your bill, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act.” And I said, “You can do that?” And he said, “Yes, I’m Chairman of the Banking committee.” And that’s exactly what he did. And because of that, we got the whole DSM (Diagnostic Statistical Manual for all mental illnesses) covered in the Parity law, which we never would have gotten if it was on its own. Just to give you a quick flash of what a Conference Committee is, it’s when the Senate sponsors meet with the House sponsors. Pete Domenici said to me, “I’ll be damned if I let those addicts sink our bill.” And frankly, he was right. If we had added addiction, there was no way the Congress of the U.S. would have passed that. There would be no way we could pass that bill today for the same reasons.

There is no advocacy out there in this country. None! Facing addiction… You could fill this whole house with the members nationwide. Faces and Voices probably would fit in the room back here. NAMI (National Alliance on Mental Illness) does a great job, but they’re a fraction of what they really represent in terms of the populations affected by these illnesses. Bottom line, the reason we don’t get anywhere on these illnesses, is the stigma is so great that no one is willing to come up like HIV-AIDS, who knows. If they could do it, we should be able to do it. But frankly, I think the stigma is even greater than even cancer. That’s the big problem.

JF: Why do you think that is? I had a conversation with someone recently on my PBS show about this. They said something to me, and I hadn’t thought of this. So much of it has to do with words. For instance, if you’re talking about someone who has “substance abuse,” what does that say as opposed to “substance disorder?” I thought about it. I realized, and I make my living with words, the words you use can be extraordinarily impactful. What do you think it is that drives this notion of the stigma that attaches to mental illness and addiction?

PK: …It cuts to the heart of it, and that is who we are as people. We’re talking about our agency, our ability to be considered of right mind. Who amongst us wants to be saddled with the label that somehow we’re not “all there,” that we’re not in full possession of our mental faculties. That, my friends, is why there’s stigma because there’s no one out there who wants to be seen in a way that’s pitiful. …There is nobody who can get past the fact that if you admit that you have one of these illnesses people are going to not only look at you different, but you’re going to have an immediate liability in dealing with them and other people for the rest of your life. They’re always going to look at you in that prism. Are they all right today? Are they on their meds? People make judgments. It’s very disconcerting.

JF: How can we combat that? Like you said, it gets to the core of who we are in the notion of your defense mechanisms and how you want to view yourself. As an aside, I interviewed an Iraq War veteran who lost both legs and part of an arm and suffered a head injury. The first day after his surgery, he was ready to get up and start his rehab, but he wouldn’t talk about his brain injury. When I asked him, he echoed what you said. He said, I can lose my arms and I can lose my legs and I can still function and remember that I was a soldier. But I can’t look my comrades in the eye if they think there’s something missing. So how do we deal with that?

Susan Head, Campaign Co-Chair & Trinitas Health Foundation Trustee

PK: …We have to deal with each other based upon a sense of compassion and not judgment, in that respect. The way we’re all conditioned is to give people value based on all of these other characteristics besides who they are as human beings, and what matters most is how you connect with someone. Mental illness and addiction do not need to impair the human connection, even while it can impair the way communication takes place because of the impairments from these illnesses. But people can show human warmth and love, and that has to be the essential element. I’m a real believer these days in seeing the spark of divinity in every person because every person has his own set of gifts. It may be more difficult to see to find those gifts in some people than in others, but if you spend time because you know we’re all children of God, and they’re going to teach you something you didn’t know before and they’re going to add to your life in some other way…that, I think, is the revolutionary change. That leads to a whole different paradigm in the way people relate to each other. That’s the paradigm that’s going to heal this stigma. It has to be a spiritual solution.