Hidden from the Nazis as a boy, TRMC’s Neurology Chief honors the women who helped him survive

By Erik Slagle

When a neurology patient recovers from injury or trauma, there’s a bit of mystery to how the brain responds—even a bit of a miracle. Dr. Bernard Schanzer has been working those miracles for more than 40 years, first as a neurology resident at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, and later as chair of the Trinitas Neurology Department, the position he holds today. His personal story, though, might be the most miraculous one of all.

Bernard and his twin brother, Henry, grew up in Belgium during the 1930s, unaware of the horrors that awaited Jewish families. In the spring of 1940, as the German Army rolled through their country, they fled with their parents and sister, Anna, to neighboring France. The children eventually found sanctuary with the Bonhomme family on a farm in Saint-Etienne, near Lyon.

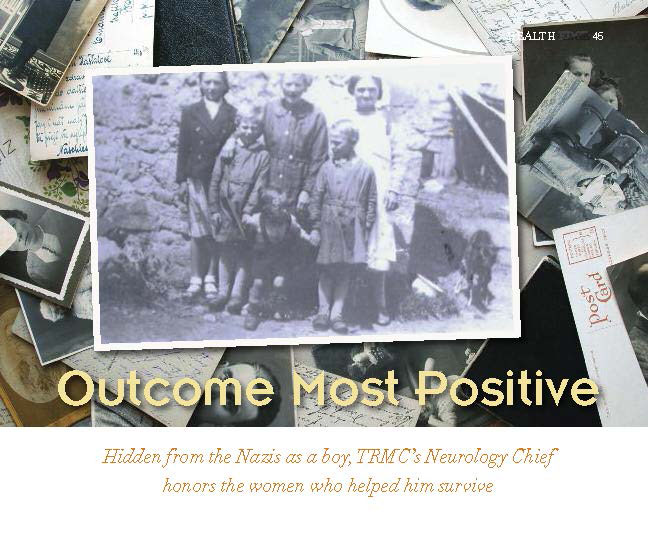

Dr. Bernard Schanzer (l) of Trinitas and his brother Henry pose for a family picture with Camille Panchaut, great-great-granddaughter and great-grandniece of the women who sheltered the Schanzer brothers from Nazis in France during World War II.

Dr. Schanzer recounts his story without a drop of melodrama. However, one can hear the exuberance pouring out in every word when he talks about the Bonhomme women. “Adolphine Dorel and her daughter, Jeanne Bonhomme, were unbelievable individuals,” he says. “For someone in France, at that time, to have this grandeur of spirit was incredible. And in many ways, Adolphine Dorel was my grandmother. My Meme.”

Hidden from the occupying Nazis, the boys fashioned yarmulkes out of cloth and recited the only Jewish prayer they knew. One night, Adolphine overheard them and asked what the prayer meant. She asked to learn it, and prayed with them to help them feel safe. The Bonhomme family was sheltering the Schanzer children—the boys with Adolphine, Anna with Jeanne—at great risk to themselves, and yet they never felt unwelcome.

“If they had been caught, they could have been deported for what they were doing, yet we never felt anything but safe and secure when we were with them,” recalls Dr. Schanzer. He talks about them through a contagious smile—testament to the light, the courage and the love that surrounded him and his siblings during that horrific epoch.

Bernard and Henry survived the war, made their way to the United States, started families of their own and became the proud grandfathers of 39 grandchildren between them. Last year, members of the Schanzer clan had the opportunity to meet Camille Ponchaut, the teenage great-great-granddaughter of Adolphine Dorel (and great-grandniece of Jeanne Bonhomme), when she came to America for a three-month study abroad program. During her stay, a delegation led by Senator Raymond Lesniak held a ceremony at the Statehouse in Trenton honoring Adolphine and Jeanne in a Resolution for their bravery.

“I knew about the role my family had played in their lives,” says Camille, “but I had never heard a detailed story before I met them. I was indeed very proud to discover more about my ancestors—how they were able to hide children during the Holocaust.”

For Senator Lesniak, the presentation of the resolution to the Schanzers and to Camille was part of a very personal storyline: Dr. Schanzer had treated the Senator following his stroke last summer. “Dr. Schanzer’s approach is very understated, and as a patient, that really builds your confidence,” Lesniak says; then he laughs. “This is how understated he is—it was during a follow-up exam that Dr. Schanzer asked me if I would do him a favor and arrange a tour of the statehouse for Camille. I said, ‘You want me to do you a favor?’ I was absolutely honored. He is a giant in the field of neurology in New Jersey.”

Dr. Schanzer says his greatest professional joys are still teaching and working with his residents. He’s seen the medical center—and the city of Elizabeth—undergo far-reaching changes since he joined the staff in 1970. “I was in residency at Albert Einstein College of Medicine,” he recalls. “A friend there referred me to what was then Elizabeth General Hospital. At that time, there were no fully trained neurologists in the area.”

These days, he oversees a department full of them.

In a profession where positive outcomes are everything, one wonders how the course of countless lives and careers might have been altered had Dr. Schanzer’s path not crossed that of Camille Ponchaut’s ancestors. “When all the lights were out in Europe,” he says, “Jeanne and Adolphine were stars. They are true examples of how we should behave and respect other people. How many people today can say they would have the courage to do what they did?”