Nazi art thieves were no match for New Jersey’s real-life Monuments Men

Over the past year, the brave men and women who devoted their knowledge and efforts to save the looted masterpieces of Western civilization during World War II have risen—mostly from the dead—into the public eye more than 70 years later. The art-specialist soldiers known as “Monuments Men” marched out of history’s shadows and right into popular culture thanks to the movie starring George Clooney, John Goodman, Bill Murray and friends. Unbeknownst to all but a handful of historians, many of these heroic, dedicated and patriotic academics—who raced against time (and the Russians) to save the great masterpieces and hidden gems of the Western world—lived, worked and trained in the Garden State.

Columbia Pictures/Fox 2000 Pictures

Among the key players in this story who hailed from our state were S. Lane Faison, Charles Parkhurst, Patrick Kelleher, Ernest DeWald and Craig Hugh Smyth, who studied at Princeton to be art historians and curators. A handful of these distinguished men went on to be directors of the Princeton University Museum of Art.

The Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Commission (MFAA), a group of 345 men and women from 13 nations, was established in 1943 as the tide of war began to turn in Europe. Known as the Monuments Men, they were recruited and trained to retrieve, safeguard and return art masterpieces, many of which had been looted from museums or confiscated from Jewish families. The Hollywood film is an amalgam of people and events. In the race to save civilization, lives and irreplaceable masterpieces, real-life art historians and curators in Europe and the United States actually began their work more than four years before Germany even declared war, and continued their endeavors for many years after the Nazis were defeated.

In anticipation of the war, museums all over Europe toiled day and night, carefully packing up sculptures and paintings and shipping them to hiding places. It was a national effort. For larger paintings, the Louvre employed scenery trucks from the Comedie-Francaise to transport them to shelters. The Mona Lisa was chauffeured in its own private railway car to her hiding place in a French chateau in the Dordogne. In 1941, the United States followed suit. Art treasures, from the newly established National Museum of Art in Washington, for example, were shipped to the safety of The Biltmore in North Carolina, as well as Fort Knox.

THE DOCTOR IS IN

The aforementioned Dr. Smyth (pictured in uniform on the preceding page) was one of the young curators who helped to move the art. A Naval reservist with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in art history from Princeton, he served as a drill sergeant and officer in the Pacific before he was tapped to head the Munich Collecting Point out of Hitler’s Munich Headquarters. Smyth’s story begins mostly when Monuments Men, the movie, ends.

According to Alexandra Smyth, his daughter, Dr. Smyth settled into Hitler’s office at the Nazi headquarters—now, appropriately, the Central Institute of Art History—as “it was the only building large enough to house the huge amounts of art for cataloguing and repatriation.” Dr. Smyth, who spoke German, immediately incurred the wrath of the U.S. military for hiring knowledgeable Germans to help with the daunting task of sorting, cataloguing and returning the tens of thousands of art treasures that were being trucked in from their hiding places—including those poorly stored in the dank salt mines shown in the 2014 movie.

“He felt it was his duty,” notes his son, Ned Smyth, “to reignite German interest in art—he considered Germany the intellectual birthplace of art history—and reawaken a positive patriotic identity of German intellectual tradition of art history…and so he hired German art experts, who were cleared by the military, to help with identifying and returning the plundered treasures.”

Eyebrows also were raised when Dr. Smyth retained the services of the German custodian who had previously maintained the Nazi headquarters for Hitler. According to his son, he wanted to get qualified Germans back to work. Later, Dr. Smyth made a point to hire German Jewish art historians to work at The Institute of Fine Arts in New York.

Photo courtesy of the Smyth family

The question of whether to return the artwork to its European owners or to send it to the U.S. for “safe-keeping” was another prickly issue. The Russians, considered any art they found as spoils of war—compensation for the devastation visited upon them by the German military—and shipped vast quantities back to Moscow. The race to seize as much of the art before it disappeared into Russian hands was one of the main plotlines in the movie.

The priceless Madonna of Bruges: loaded for transport (top) and back home in The Church of Our Lady in Belgium (bottom).

UNLIKE IKE

Dr. Smyth strongly favored returning the masterpieces to the original owners or their surviving family members. However, not all the Monuments Men agreed. John Walker, a director of the National Gallery, saw the Collecting Points as convenient way stations to appropriate European masterpieces for his new museum. He convinced General Dwight D. Eisenhower that the art should be shipped to the United States. This set up a High Noon moment that would have provided a high point for the film.

“When Eisenhower arrived at the Munich Collecting Point,” Ned Smyth recounts, “Dad had the army soldiers stationed carrying machine guns guarding the head-quarters. My dad spoke with Eisenhower…and he got the message. If anything my dad did during the war captured my young imagination, it was how he risked court-martial and the end of a promising career to save the art for Europe.”

Dr. Smyth, who passed away in 2006, lived in Alpine and went on to earn his PhD from Princeton and enjoyed a distinguished career as Director of the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU and Director of the Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies at Villa I Tatti near Florence. He also was an honorary trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His efforts in restoration of art in Europe earned him honors in both France and Germany.

WILD ABOUT HARRY

The last of the Monuments Men, 88-year-old Harry Ettlinger (pictured on page 71), lives in the Morris County town of Rockaway. Born in Germany to an affluent Jewish family, he escaped to America with his parents and siblings, starting their new life in a one-room apartment in Washington Heights.

“People told my father Go West,” Ettlinger jokes. “So we moved west…16 miles to New Jersey.”

When he returned to Germany during World War II, it was as a citizen of the United States and a soldier of its armed forces. As an army private, he was plucked from his company (which was heading to the Battle of the Bulge) to help translate for the Monuments Men. His take on the movie—where his name was changed to Sam Epstein and the handsome British actor Dimitri Leonidas portrayed him—is that it was entertaining and educational, but “to a degree, they have covered certain items that reflect what Monuments Men did. The rest is Hollywood.”

While we may feel it, not many of us actually can say we worked in the salt mines. But that’s what Ettlinger did after Germany’s surrender. For ten months he oversaw the removal of artworks that had been stored by the Nazis 700 feet below ground in salt mines to protect them from Allied bombs. There among the treasures, Ettlinger and the German miners—who had been okayed by the United States—uncovered the stained glass windows of the Cathedral of Strasburg as well as a Rembrandt self-portrait. In addition, he helped with art retrieval from Hitler’s private retreat, the Eagle’s Nest. He also helped recover and return works of art owned by the French branch of the Rothschild family, which had been stored in Neuschwanstein Castle in the Bavarian Alps.

Perhaps the most meaningful moment in this experience was retrieving his grandfather Oppenheimer’s collection from a warehouse in the Swiss spa town of Baden Baden. Ettlinger, who went on to a distinguished career as an engineer, says his grandfather was a wise man, known for his humor—wonderful traits that seem to run in the family.

Neue Gallerie NYC

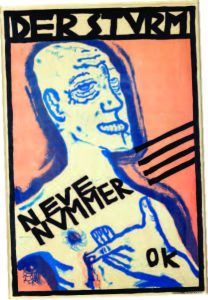

DEGENERATE ART

The Nazis’ aesthetic was intolerant towards modern art and termed it “degenerate.” Hermann Goering was charged with identifying and rounding up potentially important modern works to be sold to collectors outside Germany. This plan met with little success, and at one point an exhibition was held in Munich so that Nazi leaders could make fun of the paintings. After that, the art was supposedly burned. Much of what survived was only recently retrieved from apartments owned by the late Cornelius Gurlitt, the son of one of Hitler’s hand-picked Modern Art confiscation experts. The elder Gurlitt was tasked by the Nazis with selling the looted art through his network of contacts. Already, a valuable Matisse painting from that cache was returned to art dealer Paul Rosenberg’s descendants, one of whom is Anne Sinclair, the ex-wife of Dominique Strauss-Kahn (aka DSK), the former managing director of the World Monetary Fund. Earlier this spring, the Neue Gallerie in New York mounted a show exhibiting the stunning Degenerate Art seized by the Nazis from museums and private collections.

Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin

Whether The Monuments Men and its attendant publicity inspired people to come forward with knowledge of artwork looted or “lost” during World War II, it seems every week brings a new discovery and reunion of art with owner. Just this past April, a 17th Century painting missing during the war was sent from Germany back to Poland. And, of course, there was the startling headline last November about 1,500 works of art that were discovered behind a wall of canned food in a Munich flat. Thus the legacy of the Monuments Men is nothing if not enduring.

Editor’s Note: Sarah Rossbach grew up with stories of those who escaped the Nazi regime and those who, sadly, did not. One of the lucky German Jews, Robert von Hirsch, traded a 16th Century Cranach painting for the right to leave Germany alive with the rest of his collection. His brother, who collected original sheet music, received exit visas for himself and his family, but was ordered to leave the sheet music in Germany. His wife successfully petitioned to take her everyday china. She wrapped it in—what else?—priceless sheet music by Beethoven, Brahms and Bach.