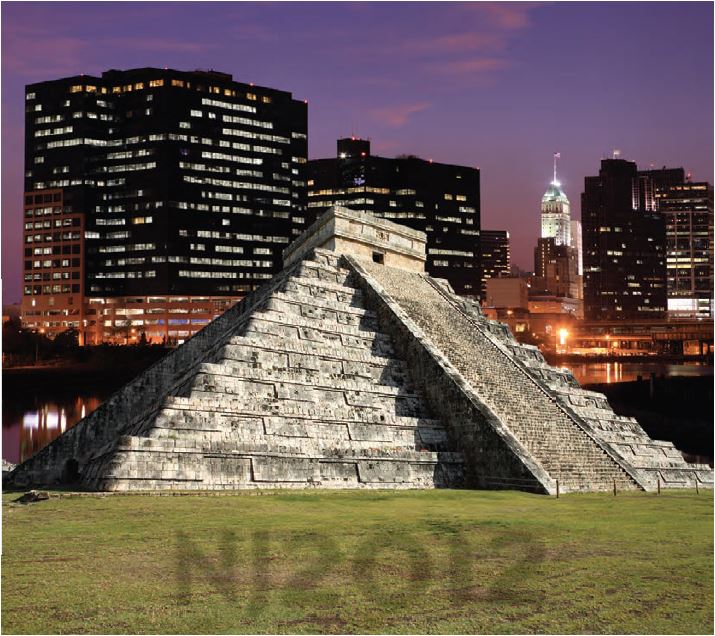

According to the Mayan calendar, on December 21, 2012, the world will come to an end. Deep down, no one really buys into this apocalyptic vision. However, it would be nice to think that New Jersey is moving away from impending doom, rather than towards it. So, the question is: Are we?

When out-of-towners think of New Jersey, they tend to picture belching smokestacks, floating medical waste and other less-than-complimentary images. Unfair as that may be, the state does have a reputation for contributing more than its fair share to the world’s pollution problem. More and more, however, we hear that New Jersey is actually a leader in the Green Movement. Everyone, it seems—from cities to businesses to individual citizens—is focused on reducing our collective carbon footprint, protecting our precious resources and promoting sustainability. Granted, there is often a credibility gap between saying you’re green and putting your money where your mouth is. But as this snapshot of “where we are” shows, in many important (and surprising) ways, the Garden State really is living up to its name. Change is never easy, especially when it comes with a price tag. And make no mistake, the initial cost of going green can be steep. Yet slowly but surely, what was once a polarizing issue is becoming a foundational one. The poster child for environmental sustainability no longer sports a beard and sandals. More often than not, it’s a guy like Mike Kerwin. Kerwin is the CEO of the Somerset County Business Partnership and founder of the state’s first Energy Council. He has been at the forefront of leading the effort to make New Jersey green. Whether it’s convincing people to walk, bike, use mass transit, bring their own bags to the grocery store or reuse water bottles, he has been committed to teaching the masses how to live more environmentally friendly. Kerwin himself sees the change. Where he once found himself lecturing people on why it’s important to live green, he now spends a lot of time providing answers to inquisitive New Jerseyans on how to embrace a cleaner, healthier and more environmentally responsible lifestyle. While everyone is still watching their pennies these days, there is a general acceptance that the added cost (and effort) required to achieve these goals is worth it in the long run. “I definitely notice that younger people—starting with my own kids—seem to embrace it,” says Kerwin of going green. “I think it’s going to be a generational shift. I think ultimately there is going to be a demand for some lifestyle changes. And I think the older generation will follow suit. The case has been made that change has to be made.”

OLD DOGS, NEW TRICKS One of the most daunting obstacles to the greening of New Jersey is breaking old habits. The same person who dutifully recycles plastic bags or keeps their tires perfectly inflated may be completely resistant to a resource-preserving technology that simply rubs people the wrong way. Ted Carey knows all too well what it feels like to bump up against logic-defying behavior. His Hillsdale company, C&C Service, markets and installs LaundryPure, a device installed above the washing machine that uses the hydrogen contained in tap water to eliminate the need for hot water and laundry detergent. It saves money. It saves energy. It extends the life of clothing. And from a cost-to-benefit standpoint, the $450 LaundryPure amortizes itself in less than two years. You’d think by now every home would have one, and that Carey would be sipping Mai Tais on some beach overlooking a secluded tropical lagoon. There is just one problem.

“The promise that the unit makes is so great, that there is a natural skepticism,” he says. “Madison Avenue has indoctrinated us to believe that you need bleach and detergent in order to have clean clothes. And when something seems too good to be true, we have a tendency to move away from it.” “We need to give a unit to Oprah,” Carey laughs.

GRIP IT & RIP IT The verdant Hyatt Hills Golf Complex, situated on the borders of Clark and Cranford, was once a condemned brown site. Now it counts among its accolades the NJTA’s Environmental Stewardship Award. Hyatt Hills was reclaimed and transformed into a destination for golfers and their families, with first-rate teaching pros and fine dining.

CAR TALK Perhaps the ultimate test of our willingness to flip the switch on the status quo is the environmentally friendly automobile. America’s car culture is deeply embedded in New Jersey. Look around the next time you’re stuck at a stoplight. Almost everyone is driving something smelly, noisy, big—or some combination of the three. At what point will Garden Staters embrace hybrids like the Prius or Volt, or the batterypowered Leaf? (Note to Nissan: Real men may not drive a car called the Leaf.) The numbers are too premature to draw any lasting conclusions, but what does exist may raise a few eyebrows. Toyota dealerships like the one in Cherry Hill reported that they were having a hard time moving the Prius—and that was before the mother company’s PR nightmare. In 2008, New Jersey ranked 11th in hybrid vehicles sold, with 6,072, despite being the 9th-most populous state. According to the salespeople in Cherry Hill, the vast majority of New Jerseyans are still in love with their SUVs, and have a hard time with the concept of plugging in a car at night. The idea of not being able to go out and just start your car immediately is still viewed as a hassle versus a benefit. Not to mention that there are conversion steps the average home must undergo before it can support a hybrid vehicle.

GROWING PAINS We are what we eat. Countless studies support this old axiom. Although only a small percentage of fruit, vegetables and dairy grown in the Garden State is organic, that number has been rising dramatically as New Jersey consumers are becoming wise to the real cost of food grown with the help of chemicals, or trucked in from thousands of miles away. Business is booming at the state’s beloved produce stands, many of which feature organic goods. Meanwhile, the major grocery chains are devoting more and more space to these products. Some even have organic house brands. All told, sales of organic foods have seen double-digit percentage increases each year for more than a decade, with some years well over 20 percent. It’s a drop in the bucket, of course, but anything that heightens consumers’ awareness of the bigger environmental picture—especially in such personal terms—is a step in the right direction. Stephen McDonald would certainly agree. He founded Applegate Farms, a Bridgewater-based natural foods business, 22 years ago. Back then he and his peers seemed to be fighting a losing battle against that other McDonald’s. Today, Applegate Farms has grown from a niche market in the health-food category to mainstream markets all across the state. McDonald credits the growth of his business and others like it to the fact that New Jersey shoppers are making informed choices about what they feed their families—significantly more informed than even a decade ago. “When you walk into a store you want to understand how it was made, and what’s in it and what is not in it,” he explains, adding that “you can eat less and eat better, and it doesn’t have to cost you any more money. And it’s better for your diet. What excites us is that people are learning and becoming more engaged.”

LEARNED BEHAVIOR

Of course, a major component of changing our longterm relationship with the earth depends on setting a good example for our children. In this regard, New Jersey schools are getting with the plan. Most if not all of the major additions and renovations that have occurred in recent years have embraced some aspect of green sensibility. One of the early trend-setters was the Willow School in Peapack-Gladstone, built from the ground up in 2001. Most of the school was constructed with salvaged and recycled materials. From the wooden beams that hold up the walls to the stonework that graces the steps, much of the physical plant is experiencing a second coming of sorts. Solar pane ls have cut energy bills by as much as 70 percent, while rainwater is recycled in a filtering tank and stored for everything but drinking water. The school even has a lunchtime garden on-site. Head of School Kate Walsh is quick to point out an added benefit to going green: an enhanced learning environment. “There’s sort of a peaceful easiness in our classrooms,” she says. “We keep cool with a lot of natural air and natural light. We don’t have a lot of sickness. It’s a very healthy environment. There are no toxins, so the kids are basically healthy and the energy is really nice. What we teach our children is that they need to be responsible decision-makers as they live in the world.”

FINDING THE RIGHT MIX

Ultimately, the agent for green change in New Jersey will be a mix of common sense and economic survival. As Randall Solomon, Executive Director of the New Jersey Sustainable State Institute at Rutgers, points out, “We want to make sure the foundation of our economy and our standard of living is built on a stable foundation that will last into the future.” As for the Mayans, one might be tempted to say that they could have used a smart guy like Solomon to give them a heads-up when their society began crumbling. Then again, New Jersey might do well to take a hard look back at the lessons learned by that vanished civilization. There are some haunting parallels. Yes, we’ll make it past 2012 all right. But the next time you find yourself complaining about food and water shortages, skyrocketing fuel prices, overbuilding and overpopulation, it might be worth remembering that in responsible, proactive stewardship of the environment lies the key to the future of the state.

Editor’s Note: Zack Burgess is the Assignments Editor for EDGE. He decided to tackle this assignment himself—with assists from architect Bob Kellner and transportation Expert Josh Leinsdorf. For more information on the energySMART program call (866) NJ–SMART.