Discovering the Galapagos

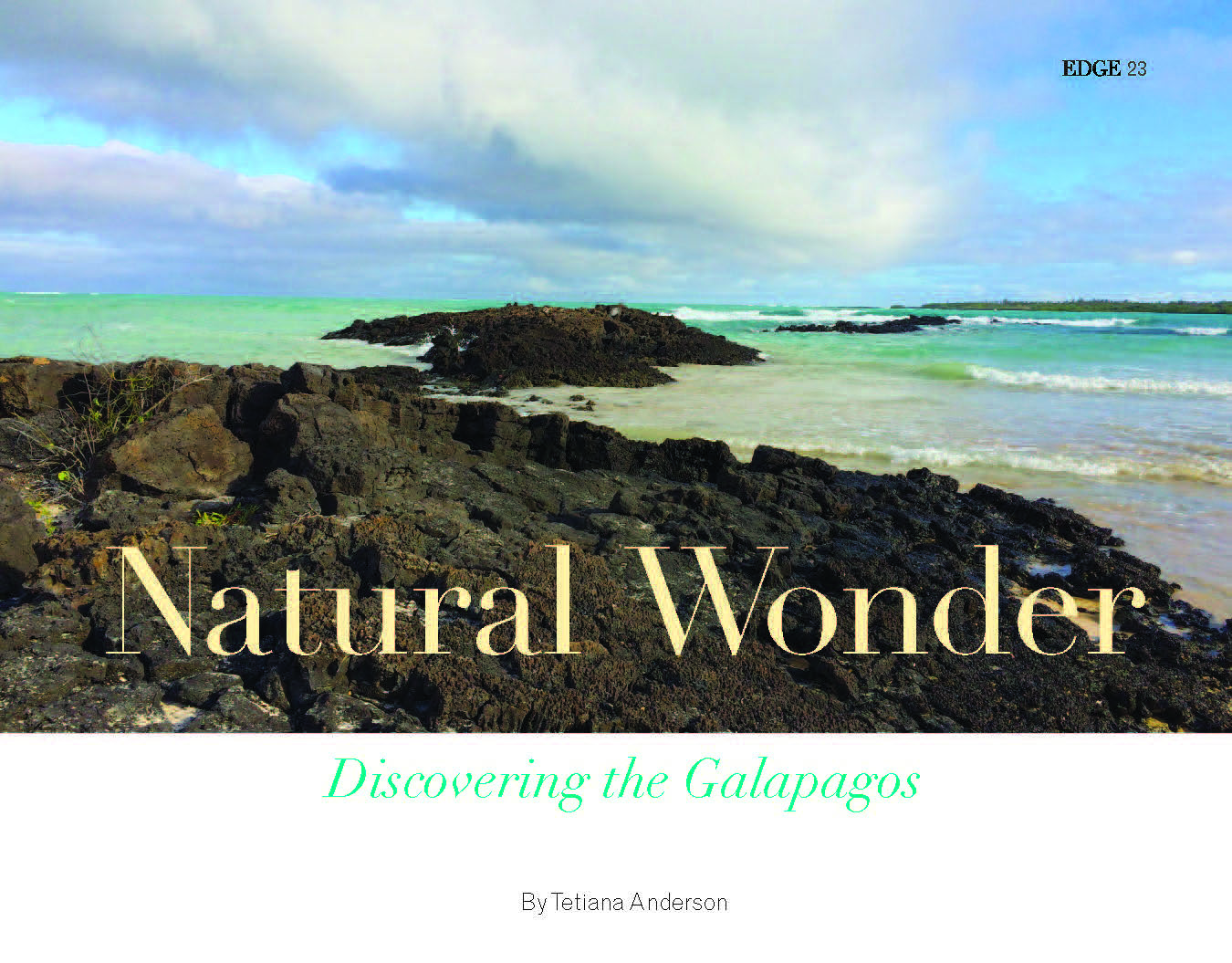

Penguins darting like torpedoes between boats moored in clear blue water. Barking sea lions jostling for the best seat on the pier’s benches. Those were the sights and sounds that greeted the water taxi as it pulled into Puerto Villamil on Isabela Island, the largest in the Galapagos archipelago. It was a dramatically different world from mainland Ecuador. Or any other place I had seen as a globetrotting journalist. In a word, it was magical.

The plan was to island-hop with the goal of seeing as many of the famously unique species as humanly possible. According to the Galapagos Conservancy, about 80 percent of the land birds, 97 percent of the reptiles and land mammals, and more than 30 percent of the plants are endemic. The best months to visit are August through November because the migratory patterns of just about all the animals, birds, reptiles and fish bring them into view on the islands during this window.

Most Americans tour the Galapagos on some kind of group excursion. Getting to know strangers from other places—and experiencing the islands through their eyes—can be part of the fun.

The members of my international crew were actually part of a sort of extended family. My Ukrainian-American mother, Christina, had retired to a seaside village in Ecuador a few years ago. Her Ecuadorian friend, Maria, came up with the idea to make the trip to the islands (which sit roughly 600 miles off the Ecuadorian coast). It turns out Maria’s parents had actually lived on one of the islands, Floriana, some 70 years ago, when her father worked for the government. Yet neither Maria nor my mother had ever been.

The members of my international crew were actually part of a sort of extended family. My Ukrainian-American mother, Christina, had retired to a seaside village in Ecuador a few years ago. Her Ecuadorian friend, Maria, came up with the idea to make the trip to the islands (which sit roughly 600 miles off the Ecuadorian coast). It turns out Maria’s parents had actually lived on one of the islands, Floriana, some 70 years ago, when her father worked for the government. Yet neither Maria nor my mother had ever been.

Maria’s husband, Washington, knew the Galapagos. He’d been stationed there while serving in the Ecuadorian military in the 1970s. Our trip would be his first time back. Maria and Washington’s adult children, Cristina and Santiago, were the fourth and fifth members of the entourage. Cristina attends university in Germany; Santiago works in Quito and had visited the Galapagos as a boy. I flew in from Washington D.C. and Cristina’s friend, Louis, traveled from the United Kingdom to make it a lucky seven.

We began our journey in Puerto Ayora, most populous town on Santa Cruz and the tourist hub of the islands. There we began our love affair with Galapagos snorkeling. The biodiversity was astounding, though not always what I’d expected. I’ve done a lot of snorkeling in warm water, including the Red Sea, where colorful fish and plants live among stunning coral formations. In the frigid waters off Santa Cruz, the colors were muted and the sea floor crowded with starfish, sea cucumbers and various non-tropical fish species. In the deep water areas sharks swam stealthily below us.

We began our journey in Puerto Ayora, most populous town on Santa Cruz and the tourist hub of the islands. There we began our love affair with Galapagos snorkeling. The biodiversity was astounding, though not always what I’d expected. I’ve done a lot of snorkeling in warm water, including the Red Sea, where colorful fish and plants live among stunning coral formations. In the frigid waters off Santa Cruz, the colors were muted and the sea floor crowded with starfish, sea cucumbers and various non-tropical fish species. In the deep water areas sharks swam stealthily below us.

Las Grietas, off Santa Cruz, translates to The Crevices. It was unforgettable. After a water taxi ride to Finch Bay and a 20-or-so-minute hike past a swanky hotel and idyllic lagoons, we swam between tall cliffs with rock walls that plunged deep into water so crystal-clear water you could see right down to the bottom.

THE LOCALS

THE LOCALS

While tourism may be the one and only industry on the islands, the attitude toward actual tourists can be uneven. For example, the owner of our hotel on Santa Cruz barely apologized for canceling one of our three reserved rooms, forcing me, my mother, Washington and Maria to be roommates for a night.

“The main income for Galapagos is tourism,” Santiago explained, “but they are not focused on the service aspect of tourism. [Many of the guides] try to trick you in order for you to hire them for everything, and they charge you whatever they want.”

Santiago, I had come to realize, possessed a highly developed sense of honor. During dinner one night a waitress mistakenly charged us for 6 entrees instead of 7. After reviewing the bill, he corrected the error as opposed to staying silent. Santiago felt everyone should at least attempt to live up to his basic standards of fairness, so when it came to the lackadaisical attitude towards tourists, as an Ecuadorian, he said he felt “annoyed and embarrassed.”

Washington added that “the taxi drivers were fine—they were quite helpful,” but, like father like son, he echoed Santiago’s sentiment about the folks in the tourist trade. “They’re kind of careless. They seem to think that, because people are going to come to the islands anyway, it doesn’t matter what they do or how you treat them. They should change that mentality.”

A few days later, on Isabela, we visited the shallower waters of the Tintoreras inlets situated just off the island. On the short Panga ride there, we saw penguins posted up on volcanic-rock islands and bright red crabs basking in the sun. Once in the water, we spotted decades-old sea turtles floating gracefully near the sea floor, and sea lions swimming close enough to grab.

“I wasn’t expecting to see the animals so close,” Louis marveled. Louis (who was half-French) turned out to be our Jacques Cousteau junior. His Go-Pro camera was always pointed at something. With Cristina’s help, he documented everything we saw above the water and below. As a bonus, Louis used his Spanish skills to extract inside information from our guides and taxi drivers.

While on Isabela we stayed in Puerto Villamil. It is a sleepy town compared to Puerta Ayora, on Santa Cruz. On the Sunday we arrived, all the shops were closed and it felt nearly uninhabited. We were lucky to find cold beer and a local woman under a walkway bridge to the beach frying up and selling the most delicious homemade meat or cheese empanadas. She made them using cassava dough, which is gluten free, instead of the flour dough I am used to in the United States.

GALAPAGOS IN A BOX

GALAPAGOS IN A BOX

The Galapagos Islands are an archipelago of volcanic islands straddling the equator in the Pacific Ocean. They were declared a province of Ecuador in 1973. About 25,000 people live on 18 primary islands and 3 smaller ones. The Galapagos Islands are in the cold-water Humboldt Current, which affects the water temperature and weather.

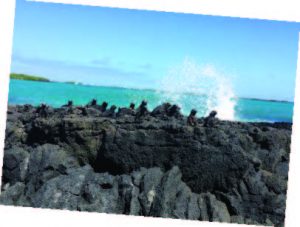

We gorged on empanadas as we took in the spectacular Malecon Cuna del Sol, a long white-sand beach surrounded by palm trees and brackish water lagoons. As I strolled along the shore later I thought my eyes deceived me. The black lava rock barrier between the sand and surf appeared to mo

ve. As I got closer I saw hundreds (and probably thousands) of land iguanas blending right in and sunning themselves.

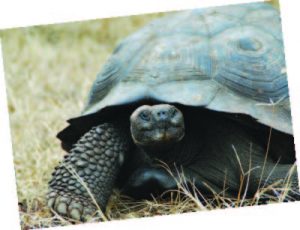

Day after day, we ticked off items on our Galapagos bucket list. We visited Rancho Primicias, a private farm and tortoise sanctuary where the giant reptiles have free range. We strolled barefoot along the beach at Garrapaterro, where flamingos nest in the surrounding lagoons. We hiked nearly

45 minute to Tortuga Bay’s beaches to kayak and watch birds and iguanas. An 8 mile round-trip walk brought us to the Wall of Tears, a 20-foot stone wall stretching more than 300 feet that was built by prisoners at a penal colony that once existed on Isabela Island.

We walked nearly everywhere. It reminded Washington of his days as a solider on the Galapagos. Weighted down by a backpack full of gear and a gun, he recalled using his machete to hack his way through raw vegetation to get from shore to shore on just about all of the islands. Today long trails leading to many of the beaches are laid with paver stones. Other paths are made of packed earth with wooden bridges across lagoon marshes. Though traversing the land is much easier than when Maria’s parents lived there, or when Washington was in uniform, one of the takeaways was that a Galapagos vacation is an active one.

My mother, who is nearly 70, is in pretty good health and full of energy. She observed that many of the activities may be too challenging for families with small children or people with a physical infirmity, even a slight one, due to some of the terrain like steep steps, long walks and the need to constantly climb in and out of small boats.

My mother, who is nearly 70, is in pretty good health and full of energy. She observed that many of the activities may be too challenging for families with small children or people with a physical infirmity, even a slight one, due to some of the terrain like steep steps, long walks and the need to constantly climb in and out of small boats.

Unanticipated costs were an occasional source of angst. We’re talking about nominal fees, such as paying for a separate water taxi after buying a full fare ferry ticket, or a small entrance fee to another island on top of the $100 tax for foreigners already paid at the main airport. But they were annoying nonetheless.

One thing that really surprised me was the amount of trash we saw. As advertised, the Galapagos Islands are an ecological wonder to be treated with great care. On the plane in, flight attendants walked through the cabin, opened the over-head bins and sprayed our luggage with some sort of anti-microbial to protect the fragile eco system from critters we may have brought with us. The effort to conserve and maintain protected breeding spaces for species like tortoises, Darwin’s finches, Blue-Footed Boobies and a range of flora and fauna is obvious and organized. That made the lax attitude toward litter even more puzzling. It was not uncommon to see trash blowing around the streets of the more populated areas, or plastic bags and cans wedged under bushes at tourist arrival points.

Where food and souvenir prices are concerned, the regulatory hand of the Ecuadorian government is always evident. That tiny carved tortoise will run $3 dollars whether you find it at the main airport on Baltra Island or at a shop on Santa Cruz. Prices in the restaurants may vary, but not by much, and are exceedingly inexpensive. And, no matter where we went, the food— including fresh ceviche, lobster, giant prawns and cassava dumplings—was delicious.

Though we could get very close to the wildlife, we respected the admonition not to touch any animals. Human scent can cause an animal to be alienated from its group. That being said, while snorkeling Cristina was practically assaulted by a sea lion determined to play.

“I wasn’t touching him…he was touching me!” she laughed, as we peeled off our wetsuits.

In the end, whatever hiccups we experienced on this adventure were completely overshadowed by the unique beauty of the Galapagos Islands and its myriad creatures. It was far from a flawlessly choreographed Disney Land experience, but that was part of the charm.

“You come here for nature and not luxury,” Louis observed. “I think in that way I wasn’t just ‘not disappointed.’ It far exceeded my expectations.”

It was a sentiment we all shared. This may have been my first adventure to the land made famous by Charles Darwin, but it certainly won’t be my last. EDGE

Editor’s Note: Tetiana Anderson writes for a wide range of newspapers, magazines and web sites and has produced news stories for CBS, CNN and The Weather Channel. She won a New York Press Club Award for her reporting in 2012, and interviewed rap star 50 Cent the last time she contributed to EDGE.