My mother. My hero. My problem?

By Ashleigh Owens

In the summer of 2017, my mother lost her life to pulmonary fibrosis, the puzzling disease that takes your life by literally taking your breath. The illness plagued her through a 16-year-long battle that began in her 30s. She never saw it coming. She was at the height of her success when the disease crept into her life, robbing her of her dreams, her mobility and, ultimately, her time. I witnessed her excruciating decline and her diminished quality of life starting when I was in grade school. During those years, I wrestled with some difficult questions about the origin of the disease, its management and, of course, whether I too might be gasping for air one day.

In the summer of 2017, my mother lost her life to pulmonary fibrosis, the puzzling disease that takes your life by literally taking your breath. The illness plagued her through a 16-year-long battle that began in her 30s. She never saw it coming. She was at the height of her success when the disease crept into her life, robbing her of her dreams, her mobility and, ultimately, her time. I witnessed her excruciating decline and her diminished quality of life starting when I was in grade school. During those years, I wrestled with some difficult questions about the origin of the disease, its management and, of course, whether I too might be gasping for air one day.

“Am I next?” I often wondered.

You may be familiar with my mother’s work. Her name was Tracey Smith-Owens and she conducted celebrity interviews (as Tracey Smith) for EDGE until her passing. She had a knack for engaging people—including Louis Gossett, Chazz Palminteri and Frank Vincent—in thoughtful conversation, and often carried those conversations past the magazine’s pages into civilian life.

You may be familiar with my mother’s work. Her name was Tracey Smith-Owens and she conducted celebrity interviews (as Tracey Smith) for EDGE until her passing. She had a knack for engaging people—including Louis Gossett, Chazz Palminteri and Frank Vincent—in thoughtful conversation, and often carried those conversations past the magazine’s pages into civilian life.

Her own words held great weight, too. Of her fight with pulmonary fibrosis, she once wrote: My freedom is limited and my assailant is a fifty-foot tube that lingers around my ankles and is connected to a concentrator to provide me with the oxygen necessary to live. My mother often spoke about the way this culprit, which had weakened her lungs, sliced into her life with no regard for the innocent people it impacted. We shared that fear and anxiety.

My mother was in the hospital for over a month until peacefully departing in her sleep. I never saw it coming; pulmonary fibrosis is full of surprises. My mother and her lungs were true fighters, the doctors told me. Her ability to survive and in many ways thrive for more than a decade-and-a-half astounded them.

My mother was in the hospital for over a month until peacefully departing in her sleep. I never saw it coming; pulmonary fibrosis is full of surprises. My mother and her lungs were true fighters, the doctors told me. Her ability to survive and in many ways thrive for more than a decade-and-a-half astounded them.

Throughout my mother’s illness, she constantly warned me to keep myself healthy. She was unable to identify a connection or source of her disease—and indeed, pulmonary fibrosis is very much a mystery. Her greatest fear was that it was genetic, that there might be some chance of me inheriting it. Although this was always in the back of my mind, I was primarily focused on being my mother’s protector during her trials and tribulations. The life I had known as an only child with a single mother, who was devoted to watching over me, was suddenly juxtaposed: I became a shield for her.

Seeing how pulmonary fibrosis affected my mother physically, mentally and emotionally could be overwhelming, especially when I was a teenager. We felt a distance from family and friends, who lacked an understanding of her condition. My mother knew she could rely on me to listen. She could count on me to be her cheerleader, to root her through her at-home medical therapies and doctor visits, to remind her of maintenance with lung exercises, and to step in for her on day-to-day tasks, as her pace and strength weakened over time. Our bond strengthened as two became one to fight against this illness.

www.istockphoto.com

My mother left me a recording of a February 2017 doctor visit, which included a conversation regarding her eligibility for a lung transplant. To get on the list involves meeting certain criteria, in her case to demonstrate how her lungs and heart coincide. This recording drove home for me the monumental medical obstacles she faced and her commitment to explore any options that would enable her to stay on this earth longer with me. The doctors in the recording seemed amazed as she described her journey, and her will to keep ongoing. They said my mother would make a great spokesperson for the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation. Hearing these words validated for me that my mother was the ultimate heroine in the fight against this life-crippling disease.

Following the loss of my mother, the fear that I might be next weighed heavily on me. It forced a certain growth. We were guardians for each other; now she wasn’t there to guard me. However, fighting alongside her all those years prompted me to explore ways I could live a healthy life that might diminish the chances of my getting this disease—and to take the initiative and see a pulmonologist early on to determine the state of my lung function. I went through a series of tests and x-rays, both of which came back with satisfactory results.

The severe (or idiopathic) pulmonary fibrosis that eventually claimed my mother usually affects people in their 50s or 60s. She was diagnosed with the disease in her 30s. She lived a decade longer than average. She was a fighter. I am in my 20s.

Fortunately, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis rarely occurs in more than one family member. But because its causes are not completely understood, no one can say with certainty that it is not hereditary. There does in fact appear to be a genetic link in certain cases where it runs in families: Two genes, TERT and TERC, are found to be mutated in about 15 percent of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis sufferers. However, not everyone who develops these mutations develops the disease. Needless to say, a lot more research needs to be done.

So am I next?

When I asked my doctor, he said where pulmonary fibrosis is concerned there is never really any guarantee, but emphasized that the disease doesn’t “have” to be hereditary. He said to live healthily and be proactive by monitoring the state of my lungs, and that everyone should be as curious and vigilant about their health as I am. You can choose to be oblivious to the inevitable, he added, but you do so at your own risk.

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute

Pulmonary Fibrosis: The Hard Facts

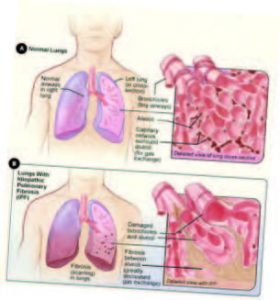

Individuals suffering from pulmonary fibrosis must struggle for every breath. Thick, scarred tissue becomes progressively stiffer until the lungs can no longer function properly, preventing oxygen from entering the bloodstream. The damage is irreparable and the cause often is unknown. In some cases, pulmonary fibrosis can be attributed to long-term exposure to environmental toxins—including airborne asbestos, metals or silica particles—or an adverse reaction to certain medicines or medical procedures, such as radiation therapy. Pulmonary fibrosis has also been linked to other conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, connective tissue disease and even pneumonia.

Medication (including steroids and antibiotics) and various therapies can ease symptoms, but only for a while. Depending on the severity of the disease, pulmonary fibrosis can progress very quickly or linger for a decade or more. Over time, it can trigger pulmonary hypertension, heart failure and respiratory failure. For some pulmonary fibrosis patients, a lung transplant is a possibility. About half of the lung transplants performed in the U.S. each year are for pulmonary fibrosis sufferers. Not all patients are good candidates for a transplant; many who are don’t live long enough to receive a suitable pair of lungs.