Courtesy of ABC-TV/Channel 7

ABC’s Michelle Charlesworth

Clawing your way to the top of the New York news business is not for the faint of heart. Staying at the top not only takes talent and tenacity, it requires the kind of authenticity that connects with viewers, who trust you to get every story right. And, of course, an occasional bit of luck. Michelle Charlesworth, longtime reporter and anchor for Channel 7, paid her dues on the way to joining the Eyewitness News team in the 1990s. However, it’s what she endured on the job—including a skin cancer scare and near miss on 9–11—that helped endear her to fans and define her as both a person and a professional. A Jersey Girl (since age 13) with a lifelong love of TV journalism, Michelle is as honest and skilled a storyteller as you’ll find on the air.

EDGE: When did the journalism bug first bite you?

MC: It started with my grandmother Jean, my dad’s mother. We would watch Sunday Morning with Charles Kuralt together. It dawned on me around age 13 that I loved learning and I loved people and I loved traveling. What if I could get paid for this and never grow up? What a great racket!

EDGE: Whom did you model yourself after?

MC: I gravitated to Judy Woodruff, who [like me] was a Duke person. She wasn’t flashy, yet she had a no-nonsense approach to finding things out that, to me, seemed very elegant. I loved to watch her do interviews on television. She had a way of breaking things down where she would stop, back up and say Please clarify this. For me, coming of age when women were achieving more power and more parity, it was great to see that work like this was possible. I also admired Diane Sawyer and Charles Kuralt—salt of the earth, everyman, a North Carolina guy—and I loved Charlie Rose, who’s the king of giving a little bit of himself so his guests give more back.

EDGE: Why broadcast journalism over print?

MC: I was always interested in the creativity that television affords one. Now I like the challenge. I’ll be out there covering the same story as my friends who are print journalists and they’re interviewing people on the phone in their car. I have to actually go get the person on television and get the pictures—that’s a challenge. But putting a story together is like making a little movie. Which is why I love television.

EDGE: What path took you from college grad to Eyewitness News in New York?

MC: I’d gone to graduate school for economics in Freiburg, Germany—I loved econ and poly sci—but at some point I thought, I don’t know what I’m doing over here. I want to go home and get a job as a reporter. I came back and sent out 208 résumés to different TV and radio stations. Nobody called me. Nobody bit. Nobody wanted to meet with me. So my mom said, “Why don’t you just go to these stations?If you pay for gas and Red Roof Inns and Denny’s, I’ll bring some library books and go with you.” So we took our station wagon and began zig-zagging through Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and all the way down to Ft. Myers. We’d stop at the stations that didn’t write me back or take my phone calls. I’d wait two minutes, two hours—however long it took to talk to somebody. I offered to work free for a month to learn if I could really make a difference and be good at this. The only news director who kind of offered me a job was at WYFF in Greenville, South Carolina. Many years later, he called me and said, “Gosh, I knew you’d do something.” I couldn’t believe he remembered me. Anyway, when we got down to Ft. Myers I called home and my dad said, “Atlantic City called. They’ve got a radio station job and an assignment desk job at the TV station.” It was WMGM Channel 40, the smallest NBC station in America. It was run out of a garage in Linwood, next to a 7–11. It paid $6 an hour. I said, “Oh my God! I’ll take it!”

EDGE: Small station, big responsibility?

MC: I worked very long hours. I think I made $14,500 that year. But I was hooked. I loved doing radio. I loved ripping stories. I loved writing stories in different ways. We didn’t have the Internet then, so I would call all the fire and police departments in the surrounding towns. I would just call and call and call. I spent my life on the telephone. I worked there as a reporter and later as a fill-in anchor for a year and a half. Next I worked down in New Bern, North Carolina for WCTI Channel 12, then WNCN Channel 17 in Raleigh for two years.

EDGE: And then you got the call.

EDGE: And then you got the call.

MC: Bart Feder, the news director in New York, saw me on somebody else’s audition tape. I was fill-in anchoring and I called out a story, saying,  “We don’t have enough information on this. I don’t even understand what we just showed. We’re going to get that for you. I apologize.” Then the co-anchor said, “This is ridiculous. I can’t believe we dropped the ball like this. That’s awful.” Well, he thought it was a great moment and he inexplicably put me and him on his tape. So the news director called me and said, “This is Bart Feder from WABC in New York. I’ve heard great things about you and I was just wondering what else you’ve done.” I said, “Sir, let me just stop you there. I loved doing radio, but I want to stay in TV.” After a long silence he said, “I’m the news director at the flagship station for WABC- hyphen-TV.” I said, “Can we go back to 45 seconds ago when I wasn’t a complete moron?” He was laughing so hard. He said, “On your contrition alone, you basically just got the job.”

“We don’t have enough information on this. I don’t even understand what we just showed. We’re going to get that for you. I apologize.” Then the co-anchor said, “This is ridiculous. I can’t believe we dropped the ball like this. That’s awful.” Well, he thought it was a great moment and he inexplicably put me and him on his tape. So the news director called me and said, “This is Bart Feder from WABC in New York. I’ve heard great things about you and I was just wondering what else you’ve done.” I said, “Sir, let me just stop you there. I loved doing radio, but I want to stay in TV.” After a long silence he said, “I’m the news director at the flagship station for WABC- hyphen-TV.” I said, “Can we go back to 45 seconds ago when I wasn’t a complete moron?” He was laughing so hard. He said, “On your contrition alone, you basically just got the job.”

Courtesy of ABC-TV/Channel 7

EDGE: 2017 will mark your 20th year with Channel 7. A lot of news people make it to the New York market only to disappear a few years later. What is it that enabled you to carve out such a niche?

MC: I am so grateful, first and foremost, that I work for a TV station that doesn’t make a lot of changes. They cling steadfastly to the choices they make, and recognize that our viewer does not like a lot of change.

EDGE: Local news is like comfort food.

MC: You’re right. But a lot of local TV stations don’t believe this. Some change all the time. I’m out in the field and I’m friendly with the reporters from other stations, but often I don’t know who these people are. At Channel 7, we have so many people who’ve been there 15, 20, 25, 30 years. We have a photographer celebrating 50 years at WABC this year. Our station is great about promoting people and staying the course. They are very rooted in You’re here. You’re good. You’re going to stay. So that doesn’t mean I’m great…but I’m good or good-plus. I’m lucky to work at a place that makes a commitment and sticks with it. Loyalty is important in this place.

EDGE: In 2000 and 2001, in a very compact amount of time, you did your skin cancer story and then reported from the scene of the trade towers on the morning of 9-11. How did those experiences, coming so close together, shape your life and career?

MC: They definitely got me hitched, those two things. I realized that we don’t know how long we’re going to be here, that there’s a timeline we don’t know about. I had the great fortune—I thought it was a misfortune at the time—to have my face blow up. I had all these stitches. I looked like a monster. Here I was crying in the bathtub and my boyfriend, Steve, gets in the tub fully clothed and embraces me. You don’t get to try guys out like that, to see if they’ll be there for better or worse. He passed the test with flying colors. I got the chance to see that he was a keeper.

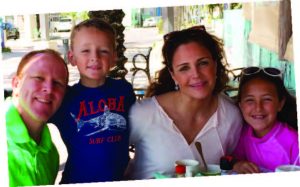

Courtesy of Michelle Charlesworth

At the worst possible time, he really came through for me. I knew that he was my partner forever—even though we weren’t even engaged yet, even though I didn’t want to get married, even though I didn’t want kids. And then on 9–11, here I was, the first person broadcasting live, from the West Side Highway. We were being told by firefighters that the whole West Side Highway was going to blow up because there is a gas main the size of a city bus that runs the length of it, and it hadn’t been turned off or secured. No one has ever really told this story. I thought I was going to die. After what I’d seen, with the two towers down, I thought anything could happen. I started almost giggling to myself as I was running, thinking Boy, am I stupid. I’ve been worrying about all the wrong things. I never got married. I never had kids. So I had this amazing epiphany. The worst day in the world had the best message for me. It really did. Now Steve and I are married and we have two kids, Isabelle and Jack. There you go.

EDGE: The skin cancer story began as someone else’s story assignment.

MC: Right! I wasn’t even supposed to be on it! It was a “Lunchtime Lipo” story. One of the feature reporters couldn’t make it that day, so here was this story about how you could stop in and get your fat sucked out. I thought, Okay…this is interesting. I’ll do it. And then as we were leaving the doctor’s office, my photographer asked about a mole on his eyebrow. I said, “Hey Frank, you’re not supposed to ask that. It’s not professional.” The doctor, Bruce Katz, said, “No, don’t worry about it…but I’d like to ask you about this thing on your cheek, next to your nose.” I thought he was kidding. I told him that every time I get a facial they just pop it. And he said, “Well, they might be popping your cancer. I want to biopsy that thing on your face right now.” Forty-eight hours later I realized he was right—I had a basal cell carcinoma.

EDGE: So had they put someone else on it, the outcome for you personally could have been very different. Isn’t it interesting how small moments can create such a profound ripple on people’s lives?

MC: Talk about a throw-away moment! Had Frank not asked about his eyebrow and had I not scolded him…had I not filled in and been on that story that day…luck, luck, luck.

EDGE: How long was the procedure and what did they do?

MC: It took all day long. First, they did a Mohs surgery, where instead of removing the cancer they take out a little bit at a time and keep checking the margin. Take a little out, go in and check, take a little out, go back and check. I ended up with a huge hole in the middle of my face that was the size of five or six dimes in a stack, which they sewed up. That took the longest time. Dr. Michael Bruck sewed me back together and he did an amazing job. He had to cut a football shape around the opening because if you just cut a circle it “puckers.” By elongating the defect, the two sides go together a lot better. Now I don’t even think about it, thank heaven, because the scar went from my nose to the side of my mouth, probably two inches. It was done so well. Dr. Bruck put it in my laugh line. I don’t even have to put makeup on it.

EDGE: In your case, you suspect that your cancer is related to where you spent the first 12 years of your life.

MC: I have two hometowns, Durham, North Carolina and Princeton, New Jersey. I was born in Durham and lived there until I was 12. My dad was a professor at Duke University. There was arsenic in the well water where we lived in Durham. It was a well-documented study done at Duke Medical School, and interestingly one of the students who did that study, Dr. Ira Davis, ended up doing the surgery on my face—which I found out during my surgery. Crazy. I was telling him that I thought people who damaged their skin by having sunburns were the ones who got skin cancer, which I never had. He asked me where I grew up. Durham. Where? Cornwallis Road. He’s like, You’ve gotta be kidding me…past Kerley? Yes. He said, “We did a study on arsenic in well water in agrarian neighborhoods and that’s exactly where you were.” I said, “Yeah, we drank well water every single day. And we have cancer elsewhere in my family.”

EDGE: The entire experience was covered nationally on Good Morning America. Talk about taking one for the team.

MC: That was surreal. That was crazy. But it was good, because my skin cancer didn’t look like skin cancer and I don’t have a lot of moles. It touched a lot of people who went and got things checked out that didn’t look like classic skin cancer—people who, like me, weren’t typical candidates for skin cancer, who thought you should be looking for moles that have odd shapes or that change in color.

EDGE: You always hear about public figures who want to use their fame to do good. In your case, you were able to do so.

MC: Yes. Hopefully, my story helped change the way we think about skin cancer. I think it did. People still come up to me and say, “Show me your scar, Michelle.”

EDGE: Really.

MC: They do…and then they show me theirs!

TAKE THAT, SUNSHINE!

TAKE THAT, SUNSHINE!

“Sunscreen is a part of my life,” says Michelle Charlesworth. “I wear it on my face and my neck 24/7, 365 days a year.”

John D’Angelo, DO Chairman/Emergency Medicine Trinitas Regional Medical Center

Dr. John D’Angelo, Chairman of Emergency Medicine at Trinitas, recommends that anyone who has had a skin cancer scare do the same. As for everyone else, sunscreen is a must any time you are likely to be exposed to the sun for long periods of time. What’s a long period?

“The sun’s ultraviolet rays can damage unprotected skin in as little as 15 minutes,” says Dr. D’Angelo. “Wear sunscreen with UVA and UVB protection with an SPF of 15 or higher and don’t be shy about reapplying it often.”

Some folks, he adds, need to be more vigilant than others, including those with light-colored skin, red or blonde hair, multiple moles or a history of sunburns.

“And obviously, if you have a personal or family history of skin cancer, like Michelle, you need to protect yourself at all times. And everyone should schedule routine skin exams with their physician or dermatologist.”

Editor’s Note: Michelle’s father, professor James H. Charlesworth, is still teaching at Princeton, where he is director of the Dead Sea Scrolls Project. Special thanks to Rob Rubilla for setting this interview in motion.