Me and My Elephant

As a child I had no interest in Nancy Drew, or Jo of Little Women. Pippi Longstocking had yet to appear, but even had she arrived a few decades sooner, I’m sure I would have ignored her as well. For me, the very center of my imaginary world was Toomai the Elephant Boy. Toomai of the Elephants was just one of Rudyard Kipling’s marvelous contributions to childhood. Along with millions of other children in any of 70 languages, I was hooked by the Just So Stories in general, by Toomai in particular. Toomai who bullied his elephant. Who shouted commands and stamped his bare foot when his elephant dared not to obey him on the instant.

As a child I had no interest in Nancy Drew, or Jo of Little Women. Pippi Longstocking had yet to appear, but even had she arrived a few decades sooner, I’m sure I would have ignored her as well. For me, the very center of my imaginary world was Toomai the Elephant Boy. Toomai of the Elephants was just one of Rudyard Kipling’s marvelous contributions to childhood. Along with millions of other children in any of 70 languages, I was hooked by the Just So Stories in general, by Toomai in particular. Toomai who bullied his elephant. Who shouted commands and stamped his bare foot when his elephant dared not to obey him on the instant.  Atop his elephant, Toomai rode fearlessly through the jungles of India. Together, child and beast were impervious to all authority of his elders. Toomai and his elephant. The stuff of dreams! So it was that when I first read about Patara Farm in Thailand—and its program entitled “Own an Elephant for a Day”—I knew I had no choice. Patara Farm is located about an hour’s jeep ride outside of Chiang Mai in Northern Thailand. The owner of the farm and the inspiration for the program is a soft-spoken, 37-year-old conservationist, named Theerapat Trungprakan. (“Please, just call me Pat.”) My day of elephant ownership begins in the cool of the morning. Along with seven other would-be elephant owners (groups are limited to eight), I arrive at the 100-acre property carved out of lush woodlands and tropical verdure. Patara is home for Pat, his wife, Dow, three very young sons and 28 elephants. It’s a huge undertaking. To help him, Pat has a staff of 18 local boys, one of whom leads us from the road where our jeeps were parked, along an improvised narrow boardwalk, across a stretch of marsh to a thatched shelter, where Pat greets us. Every inch the attentive host, Pat ushers us to seats on hand-hewn benches. As we help ourselves to fruits and juices, he introduces himself and his life’s work, beginning by sketching for us the story of how elephants were domesticated 2,500 years ago in India, where they were first captured in the wild, tamed and trained. Generation after generation of these massive mammals were bred for docility, agility and robust health. The art—and what an art it is!—of training an elephant for a lifetime of productive work was handed down, father-to-son, and about 500 years ago was passed from India to Thailand. Pat tosses in a few elephant facts: An elephant has a life span of 60 to 70 years.

Atop his elephant, Toomai rode fearlessly through the jungles of India. Together, child and beast were impervious to all authority of his elders. Toomai and his elephant. The stuff of dreams! So it was that when I first read about Patara Farm in Thailand—and its program entitled “Own an Elephant for a Day”—I knew I had no choice. Patara Farm is located about an hour’s jeep ride outside of Chiang Mai in Northern Thailand. The owner of the farm and the inspiration for the program is a soft-spoken, 37-year-old conservationist, named Theerapat Trungprakan. (“Please, just call me Pat.”) My day of elephant ownership begins in the cool of the morning. Along with seven other would-be elephant owners (groups are limited to eight), I arrive at the 100-acre property carved out of lush woodlands and tropical verdure. Patara is home for Pat, his wife, Dow, three very young sons and 28 elephants. It’s a huge undertaking. To help him, Pat has a staff of 18 local boys, one of whom leads us from the road where our jeeps were parked, along an improvised narrow boardwalk, across a stretch of marsh to a thatched shelter, where Pat greets us. Every inch the attentive host, Pat ushers us to seats on hand-hewn benches. As we help ourselves to fruits and juices, he introduces himself and his life’s work, beginning by sketching for us the story of how elephants were domesticated 2,500 years ago in India, where they were first captured in the wild, tamed and trained. Generation after generation of these massive mammals were bred for docility, agility and robust health. The art—and what an art it is!—of training an elephant for a lifetime of productive work was handed down, father-to-son, and about 500 years ago was passed from India to Thailand. Pat tosses in a few elephant facts: An elephant has a life span of 60 to 70 years. Female elephants often give birth right up through the age of 50. A newborn weighs in at about 260 pounds, delivered after 22 months of gestation. A full-grown elephant can weigh as much as 11,000 pounds and will stand as high as 10 feet at the shoulder. Elephants are herbivores, who every day pack away 350 to 400 pounds of plant material. Sugar cane and bananas rank high on their list of Favorite Foods. As we listen, we gaze out into the surrounding woodlands, where elephants stroll by at their leisure, thoughtfully munching untidy mouthfuls of shrubbery. The warm, moist air carries a strong animal musk. It smells marvelous. It bespeaks nature unbounded. Nature in the raw; somehow it conveys an elemental certainty. It’s as if, however briefly, we are transported beyond the trivia, the excess and, yes, the absurdity of human events into a realm of uncorrupted truth. To call Pat impassioned on the subject of elephants is a massive understatement. His understanding of these extraordinary animals is exceeded only by the love and respect he bears them. He tells us that there was a time when elephants roamed vast areas of Asia and Africa— before man made fire, before man stood upright, before farmers farmed. Their numbers were legion.

Female elephants often give birth right up through the age of 50. A newborn weighs in at about 260 pounds, delivered after 22 months of gestation. A full-grown elephant can weigh as much as 11,000 pounds and will stand as high as 10 feet at the shoulder. Elephants are herbivores, who every day pack away 350 to 400 pounds of plant material. Sugar cane and bananas rank high on their list of Favorite Foods. As we listen, we gaze out into the surrounding woodlands, where elephants stroll by at their leisure, thoughtfully munching untidy mouthfuls of shrubbery. The warm, moist air carries a strong animal musk. It smells marvelous. It bespeaks nature unbounded. Nature in the raw; somehow it conveys an elemental certainty. It’s as if, however briefly, we are transported beyond the trivia, the excess and, yes, the absurdity of human events into a realm of uncorrupted truth. To call Pat impassioned on the subject of elephants is a massive understatement. His understanding of these extraordinary animals is exceeded only by the love and respect he bears them. He tells us that there was a time when elephants roamed vast areas of Asia and Africa— before man made fire, before man stood upright, before farmers farmed. Their numbers were legion. Today, it is estimated that in the whole world there are probably no more than 52,000 left in the wild. Every passing year sees their numbers decline. Where once they were used as beasts of burden, as transport, as invaluable aids in forestry, in heavy labor of every kind, today they are used only in ceremonial pageants and in a few instances as tourist attractions. “In 20 years, maybe less, elephants could become extinct. Except in a zoo, they will cease to exist.” Pat pauses, then resumes. “Extinction,” he tells us, “is forever.” He turns and we read those very words on the back of his bright red Tshirt. Each of us is paired up with an elephant. Ours for the day. I’m introduced to Nui, a 14-year old female. Tethered by one massive leg she stands in the shade of a giant mango tree. I approach with delight generously mixed with total ignorance. Meet a dog, hold out your open palm. Meet a horse, speak softly, move slowly, stroke the neck and muzzle. But meet an elephant? Toomai, help me! I reach up and run my hand over the crinkly skin.

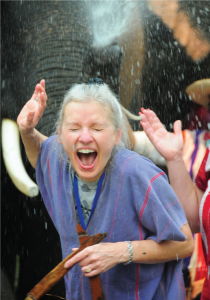

Today, it is estimated that in the whole world there are probably no more than 52,000 left in the wild. Every passing year sees their numbers decline. Where once they were used as beasts of burden, as transport, as invaluable aids in forestry, in heavy labor of every kind, today they are used only in ceremonial pageants and in a few instances as tourist attractions. “In 20 years, maybe less, elephants could become extinct. Except in a zoo, they will cease to exist.” Pat pauses, then resumes. “Extinction,” he tells us, “is forever.” He turns and we read those very words on the back of his bright red Tshirt. Each of us is paired up with an elephant. Ours for the day. I’m introduced to Nui, a 14-year old female. Tethered by one massive leg she stands in the shade of a giant mango tree. I approach with delight generously mixed with total ignorance. Meet a dog, hold out your open palm. Meet a horse, speak softly, move slowly, stroke the neck and muzzle. But meet an elephant? Toomai, help me! I reach up and run my hand over the crinkly skin. Surprise! It’s covered with short, black, bristly hairs that are all but invisible unless you’re standing very close. She’s so big that even on tiptoe I can hardly reach higher than her eyes. By way of introduction I feed her about 20 pounds of corn cobs and sugarcane stalks provided by Tang, one of Pat’s helpers. It’s a tricky business, because each offering has to be poked directly into her mouth, which is obstructed by her trunk which curls and uncurls in unpredictable ways. “Good Nui,” I tell her, “good girl,” forgetting that though English is my language, her language is Thai. As the sun climbs toward the zenith of noon, Pat shows us how to command our elephants to lie down in order to sweep their backs free of dirt, leaves and twigs with a fistful of palm fronds. Once tidied up, I offer Nui the palm fronds, which she consumes in a single messy mouthful. Bath time! The approved technique by which one moves one’s elephant out from under a mango tree down to the river some 200 yards away consists of taking a firm grip on the edge of one ear and telling her “My-my-my-my,” the Thai word for “Come.” Slowly but surely, we progress to the river’s edge. There I release my hold, step aside and Nui wades in to join the other seven elephants. It’s playtime. With much swooshing and spraying, much splashing and squirting, all the elephants—along with their owners-for-the day—have a watery free-for-all.

Surprise! It’s covered with short, black, bristly hairs that are all but invisible unless you’re standing very close. She’s so big that even on tiptoe I can hardly reach higher than her eyes. By way of introduction I feed her about 20 pounds of corn cobs and sugarcane stalks provided by Tang, one of Pat’s helpers. It’s a tricky business, because each offering has to be poked directly into her mouth, which is obstructed by her trunk which curls and uncurls in unpredictable ways. “Good Nui,” I tell her, “good girl,” forgetting that though English is my language, her language is Thai. As the sun climbs toward the zenith of noon, Pat shows us how to command our elephants to lie down in order to sweep their backs free of dirt, leaves and twigs with a fistful of palm fronds. Once tidied up, I offer Nui the palm fronds, which she consumes in a single messy mouthful. Bath time! The approved technique by which one moves one’s elephant out from under a mango tree down to the river some 200 yards away consists of taking a firm grip on the edge of one ear and telling her “My-my-my-my,” the Thai word for “Come.” Slowly but surely, we progress to the river’s edge. There I release my hold, step aside and Nui wades in to join the other seven elephants. It’s playtime. With much swooshing and spraying, much splashing and squirting, all the elephants—along with their owners-for-the day—have a watery free-for-all.  Pat and his helpers provide us with buckets and scrub brushes; when our charges lie down, we are shown how to baste them and scrub them, an exercise which Nui and I enjoy in equal measure. At last, my Toomai moment arrives! It’s time to climb on board. Pat demonstrates four different ways of handling it. As I recall, Toomai would say the word and his elephant would wrap his trunk around him and lift him onto his head. But that method is not included in the four styles we are shown. I choose what appears to be the easiest and in so doing, I find there is no “easy” (much less “easiest”). Still, I make it onto Nui’s head by standing on her curled front leg and hauling myself up by shamelessly using her ear as a handhold. Once seated, Toomai-like, I tuck my bare feet one foot behind each ear, and speak the magic words that Nui clearly understands. It’s “Sai” for left and “Kwa” for right. We fall into parade formation and, with Pat in the lead, we make our way, slowly and stately, through a mile or so of woodlands from which we emerge in a glen into which tumbles a sparkling waterfall—the perfect antidote for Thailand’s torrid temperatures. A delectable picnic lunch of unidentifiable Thai dishes has been laid out for us atop layers of banana leaves. While we set to, our elephants gambol in the water, shooting trunksful of water at each other, not caring one whit if they soak their owners in the process. It’s late afternoon by the time we make our way back to Patara Farm. I’m soaked, exhausted, exhilarated. Nui and I have bonded. She kneels down so I can slither off her and in farewell I stroke her trunk, whispering endearments. “Lah gorn, Nui” I tell her. Remembering my Kipling, I know full well that Nui will never forget me. It goes without saying that I will never forget Nui. We bid Pat farewell. Our group heads for the jeeps and I think to myself, Well, Toomai, at long last, I made it! EDGE

Pat and his helpers provide us with buckets and scrub brushes; when our charges lie down, we are shown how to baste them and scrub them, an exercise which Nui and I enjoy in equal measure. At last, my Toomai moment arrives! It’s time to climb on board. Pat demonstrates four different ways of handling it. As I recall, Toomai would say the word and his elephant would wrap his trunk around him and lift him onto his head. But that method is not included in the four styles we are shown. I choose what appears to be the easiest and in so doing, I find there is no “easy” (much less “easiest”). Still, I make it onto Nui’s head by standing on her curled front leg and hauling myself up by shamelessly using her ear as a handhold. Once seated, Toomai-like, I tuck my bare feet one foot behind each ear, and speak the magic words that Nui clearly understands. It’s “Sai” for left and “Kwa” for right. We fall into parade formation and, with Pat in the lead, we make our way, slowly and stately, through a mile or so of woodlands from which we emerge in a glen into which tumbles a sparkling waterfall—the perfect antidote for Thailand’s torrid temperatures. A delectable picnic lunch of unidentifiable Thai dishes has been laid out for us atop layers of banana leaves. While we set to, our elephants gambol in the water, shooting trunksful of water at each other, not caring one whit if they soak their owners in the process. It’s late afternoon by the time we make our way back to Patara Farm. I’m soaked, exhausted, exhilarated. Nui and I have bonded. She kneels down so I can slither off her and in farewell I stroke her trunk, whispering endearments. “Lah gorn, Nui” I tell her. Remembering my Kipling, I know full well that Nui will never forget me. It goes without saying that I will never forget Nui. We bid Pat farewell. Our group heads for the jeeps and I think to myself, Well, Toomai, at long last, I made it! EDGE

Editor’s Note: Linda Stewart is a syndicated travel writer whose stories appear in national magazines and newspapers. For more information on Patara Elephant Farm, log onto pataraelephantfarm.rom or telephone 081.992.2551.