“Makeda ups the ante for restaurants that aim to do right by other than animal products.”

338 George St., New Brunswick. Phone: 732.545.5115

Hours: Lunch, Monday through Friday from 11:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Saturday from noon to 4 p.m. Dinner, Monday through Thursday from 4 to 10:30 p.m., Friday and Saturday from 4 to midnight and Sunday from noon to 10:30 p.m. The bar is open until 1 a.m. on weeknights and until 2 a.m. on Friday and Saturday nights. It’s open until midnight on Sundays. There is live music on Friday and Saturday nights. Reservations are accepted, as are all major credit cards. Prices: Appetizers and salads, $7.50 to $15.50. Entrees: $24 to $37. Vegetarian entrees are $15 to $25.50.

I wasn’t surprised when a professor pal of mine at Rutgers suggested Makeda as our lunch spot: We both love learning, adventure at the table, and foods that take us away from anything resembling an edible routine.

Makeda, the first Ethiopian restaurant to make a fine-dining statement in New Jersey, is a natural for New Brunswick, a college town that plays home to both mainstream and ethnic restaurants, lavishing equal affection on well-played versions of the normal and the novel. My friend and I were in complete agreement: Why grab a sandwich billed on a thousand menus when we could gab over fare rarely offered elsewhere? Makeda it was.

It’s a restaurant that pops into my mind whenever I want to veer from anything standard-issue. It tends to delight newcomers even as it defies expectations, for the menu is a trip to a land of new ingredients and new juxtapositions of familiar foods.

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

The eating itself flies in the face of American tradition. The conduit of food between platter and mouth is Ethiopia’s beloved injera bread, a spongy, grainy number that’s something like a thick, large crepe in appearance, but tastes engagingly sour and is used to scoop up pretty much everything served at Makeda. That mild lemony flavor clicks on all cylinders with a variety of headliners, including lamb, chicken, seafood, beef and vegetables. Every time I’m at Makeda and wrap strips of faintly sweet lamb with vigorously seasoned onions in a torn-off piece of injera and warm to the scheme of everything-in-one-bite, I wonder why more contemporary chefs don’t steal from Ethiopia’s culinary playbook.

That’s exactly what friends who went with me one recent night to sample around Makeda’s menu thought. And if they were hesitant about diving into the communal platters concocted by the kitchen so we could better share the diverse dishes we’d ordered, they certainly didn’t act a smidgen shy.

Minchetabesh, ground sirloin infused with cardamom, garlic and ginger, and liberally doused with white pepper, is pan-seared with sliced onions to make it ready for rolling in the tangy injera. Though the concept may have you thinking hamburger, the finished dish is high-toned and beguiling. It offers the same attitude as the zil-zil, those strips of lamb marinated in Ethiopian honey wine with onions and garlic, then fried in butter which makes the meat crusty, but locks in the seasonings and juices. Cosseted in the injera, it’s something my dining companions can’t stop eating.

We can’t stop talking about how plain old delicious the doro wat is, a classic Ethiopian entrée of bone-in chicken parts that have done time in a lemon marinade before being briskly sautéed with the reigning triumvirate of fenugreek, ginger and garlic. The dish is finished with a dash or three of berbere, a feisty spice mixture that’s heavy on the ground chilies but tamed by baking spices – nutmeg, cinnamon and cloves. We slice the hard-boiled egg served with our chicken and tuck every component of the dish into the foamy bread. My pals have gotten the hang of what, only a short time earlier, was newfangled finger food.

Ethiopian food is vegetable- and pulse-centric, and Makeda ups the ante for restaurants that aim to do right by other than animal products. Take the mesir wat, lentils and onions slow-cooked with garlic and ginger in a berbere that’s calmer than the chilies-rich mixture used in the doro wat. It’s both comforting and cunning, a stew that’s decidedly rustic, but sophisticated in its layering of multiple warming seasonings. If you want more vigorously spiced lentils, go for the mesir azefah, which plays green lentils off a hotter backdrop of accents that include jalapenos, mustard seeds and white pepper. Served cold, it’s something you might want to share as a starter.

Speaking of which, appetizers aren’t part of a typical meal in Ethiopia. So the kitchen crew here, guided by owner Ogbe Guobadia, borrows from cuisines in North Africa, most notably Morocco, for its starters and even throws in a salad or two. Skip the salads, which truly do seem out of place, and kick off dinner with loubia, a sauté of string beans in lots of parsley given a lift from cumin, ginger and garlic. They’re pleasingly soft, as many vegetables are in the Middle East, Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, and work in tandem with the zaalouk, a perky chop of eggplant pan-fried with the same accents, then sprayed with fresh lemon juice before hitting the plate.

Photo credit: iStockphoto/Thinkstock

I usually snag the kefta when dining at Makeda, finding those Moroccan meatballs powered by crushed red pepper irresistible, but this time out I ordered a accented opener of shrimp simmered in peppery orange juice, then served with wedges of orange juice and tomatoes. The shrimp were overcooked and the orange not integrated into the shellfish. Next time, I’ll stick with the meatballs.

I wish Makeda wouldn’t stick to its all-American desserts. The folks here can do better than carrot cake that’s done too much time poorly covered in the fridge. Even if it’s something very simple—again borrowing from Morocco—such as cookies studded with nigella seeds or oranges in orange flower water, it would do more in keeping with the mission of Makeda. Right now, there are no grand finales at a restaurant that deserves a rousing finish.

Makeda, born in 1996, is a fixture in New Brunswick. People who live in the city, those who work at or attend Rutgers, are proud to show it off to visitors: It’s unlike anything else in the state, it sports a lively scene—especially on Friday and Saturday nights when live bands take center stage—and it proves restaurants in New Jersey aren’t always focused on Italian-American standards. Give Makeda an “A” for inspiration.

Editor’s Note: Andy Clurfeld is a former editor of Zagat New Jersey. The longtime food critic for the Asbury Park Press also has been published in Gourmet, Saveur and Town & Country, and on epicurious.com. Her post-Sandy stories for NBCNewYork.com rank among the finest media reporting on the superstorm’s aftermath and recovery.

Exotic Collegiate

Exotic Collegiate

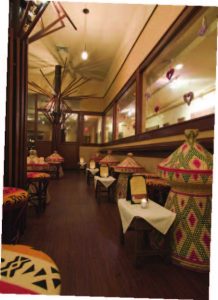

If you ever went to Tumulty’s in the old days, Makeda may strike you as a brave new century in college town dining. It’s got the requisite large and happy bar and a space that, if the ceilings weren’t so high, could be called cavernous. But comparisons to a typical collegiate hangout stop there.

Makeda sports African artwork through its dining spaces, both in the private rooms and the main dining areas. A long banquette fronted by tables for two (or four) is upholstered in colorful fabric that avoids stereotype but feels vividly African. The wood and glass that define the spaces are angular and striking. It’s a scene that melds modern times with Ethiopian/African traditions.