Forget about Chinese spy balloons…New Jersey’s relationship with lighter-than-air flight dates back 230 years.

Granger Collection

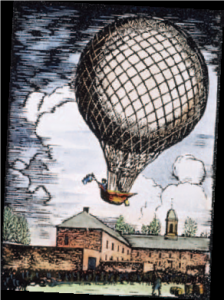

January 9, 1793

French balloonist Jean-Pierre Blanchard, author of the first-ever balloon flight in Paris in 1784, brought his marvel to America in the winter of 1793. He arranged a demonstration in Philadelphia in front of George Washington and, legend has it, four future presidents: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe. Blanchard ascended from the prison yard at the Walnut Street Jail, crossed the Delaware River and overflew Camden before turning south and landing safely in Deptford in Gloucester County, New Jersey. America’s first lighter-than-air flight concluded near the famous Clement Oak, where a plaque commemorated the event before the majestic tree was lost in a storm. Blanchard, who did not speak English, carried a letter from Washington instructing the recipient to deliver the Frenchman and his balloon back to Philadelphia. Which would make it the first air mail flight in the US, as well.

Upper Case Editorial

Upper Case Editorial

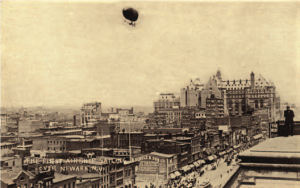

October 15, 1910

The first attempt to cross the Atlantic Ocean by air lifted off from Atlantic City in the autumn of 1910. The airship America, designed and piloted by Walter Wellman and Melvin Vaniman (left), made its way north, passing over Newark and then continuing northeast up the coast to Maine before heading out over the ocean. Near the end of the journey’s third day, the crew of six (plus Vainman’s cat) had to abort the flight after the motor died, climbing down a rope to a lifeboat before being picked up by a passing steamer. America was originally conceived as a means of flying over the North Pole, but was reconfigured for the transatlantic flight after Robert Peary beat Wellman to it. The airship was 228 feet long and 52 feet in diameter, and was constructed of three layers of silk and cotton fabric, bonded with rubber. Although the 1910 flight lasted just 71 ½ hours, it still set a world record for time aloft.

Upper Case Editorial

July 2, 1912

Undaunted by his failure to cross the ocean in 1910, Melvin Vaniman built a 258-foot airship funded by Goodyear named Akron. The large crowd gathered near the beach in Atlantic City to witness Vaniman’s departure were horrified when, just minutes later, the hydrogen-filled craft exploded, engulfing the gondola in flames as it plunged 2,400 feet into an inlet. Vaniman, his brother Calvin and three crewmembers died in the crash. An investigation determined that the balloon ruptured due to excessive internal pressure—it had been overinflated.

Alexander Cohrs

October 15, 1928

New Jersey served as the port of entry for the first-ever transatlantic commercial passenger air service when the Graf Zeppelin (LZ 127) arrived at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station, in Manchester. The sleek 776-foot rigid airship was named in honor of Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (Graf is German for Count) and constructed over the course of 18 months by Ludwig Durr. The gondola, which contained the flight deck, 10 passenger cabins, two restrooms and a common area, measured slightly less than 100 feet from end to end. The flight from Germany took 111 hours, 44 minutes and was slowed by a damaged tail fin. While repairs were being completed, a distress call was made but no other radio transmission followed, leading many to believe that airship had fallen into the ocean. On its return flight, the Graf Zeppelin carried Clara Adams, an early aviation celebrity who helped popularize air travel, as well as a stowaway who was discovered hiding in the mail room. The craft was greeted in Germany by President Paul von Hindenberg.

US War Department

US Naval History and Heritage Command

April 4, 1933

What are the odds that two airships named Akron would perish off the coast of New Jersey? Incredibly, that’s just what happened when the US Navy’s Akron—the world’s first flying aircraft carrier—plunged tail-down into the Atlantic in a violent thunderstorm. The resulting 73 deaths made it the worst air disaster in history at the time and the deadliest airship crash ever; only three people survived. A Navy blimp sent out to search for survivors also went into the sea, killing two more men. An investigation determined that virtually all of the Akron deaths had resulted from hypothermia. No lifejackets were issued to the crew, and they were unable to launch lifeboats after the airship hit the water. The accident ended the Navy’s airship experiment, as one of the dead was Rear Admiral William Moffett (left)—among the program’s main proponents.

German Federal Archives

May 6, 1937

The era of airship transportation ended more or less where it began when the Hindenberg exploded as it attempted to land in the early evening at Lakehurst. In 1936, the Hindenberg had completed 10 round trips between Germany and the US without incident, and the May flight was the first of 10 more scheduled for 1937. The airship was only half-full on the flight across the Atlantic, but was fully booked for the return leg of its journey. Many of those passengers were planning to attend the coronation of England’s George VI (of The King’s Speech fame). Poor weather had delayed the flight and prompted Captain Max Pruss to plot a course over Manhattan, stopping traffic and sending office workers racing to catch a glimpse of the craft. He later gave passengers a two-hour “tour” of the Jersey Shore while waiting for the weather to clear. At 7:25 pm, witnesses noticed a blue flame moments before a fire broke out at the rear of the Hindenberg, quickly engulfing the entire airship. The disaster was captured by multiple newsreel cameras and covered live on radio by Herbert Morrison. Of the 97 occupants of the Hindenberg, 62 were able to escape with their lives. Those who perished were badly burned, victims of smoke inhalation or jumped from an excessive height. One member of the ground crew succumbed to his injuries a day later.

German Federal Archives

May 23, 1968

Although the heyday of lighter-than-air aviation had long since passed, Hangar No. 1 at Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst, built in 1921, was still in use more than five decades later when it was designated as a National Landmark. The enormous hangar served as home base for four legendary rigid airships—Shenandoah, Los Angeles, Akron and Macon—and was America’s only stopping place for commercial airships (including the Graf Zeppelin and Hindenberg). The hangar measured 996 feet long and was wide enough to accommodate two airships side-by-side. Today, Hangar No. 1 serves as a base for multiple educational programs.

US Dept. of the Interior

April 26, 1986

Everything that flies can only weigh so much before it won’t fly anymore. There is a limit, for instance, to what a blimp can lift. And a limit to what a helicopter can lift. But what about a blimp plus four helicopters? That question was answered in 1986 by the Piasecki PA-p7 Helistat, a helium balloon with four H-34J choppers bolted to it framework. The experimental craft was ordered up by the US Forest Service for harvesting timber from inaccessible terrain. If this sounds a little crazy, well, it was. The craft performed well until a test flight that summer, when a gust of wind moments after liftoff caused one of the helicopters to break free, with its rotor slicing into the gas bag. The ensuing vibration caused the remaining three to break free, sending the Helistat to the ground in what would be its final flight.

The New York Times Co.

July 4, 1993

The summer of 1993 marked the debut of the 165-foot blimp “Bigfoot,” which was headed for Linden on July 4th when part of its tail assembly came loose and tore a gash in its nylon skin as it traveled down the Hudson River. Strollers along Boulevard East stopped in their tracks to watch the airship—emblazoned with a giant Pizza Hut logo—slowly deflate between New York City and northern Hudson County and veer off toward midtown Manhattan. Bigfoot’s descent came to an end on the side of a building on West 53rd Street. The pilot (a Goodyear veteran of 35 years) and his co-pilot, were lucky to walk away with minor injuries. New York Mayor David Dinkins, who was often out of town when weird things happened in the city, was scheduled to fly to Israel that evening. After surveying the scene, he joked, “The first thought I had was, man, I haven’t even gotten on a plane yet!”