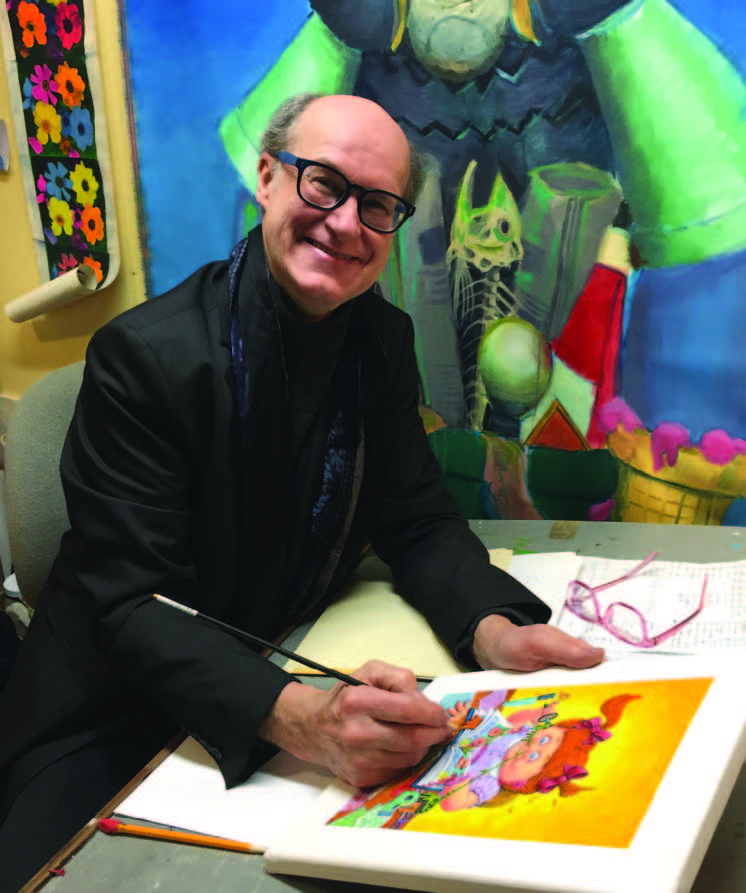

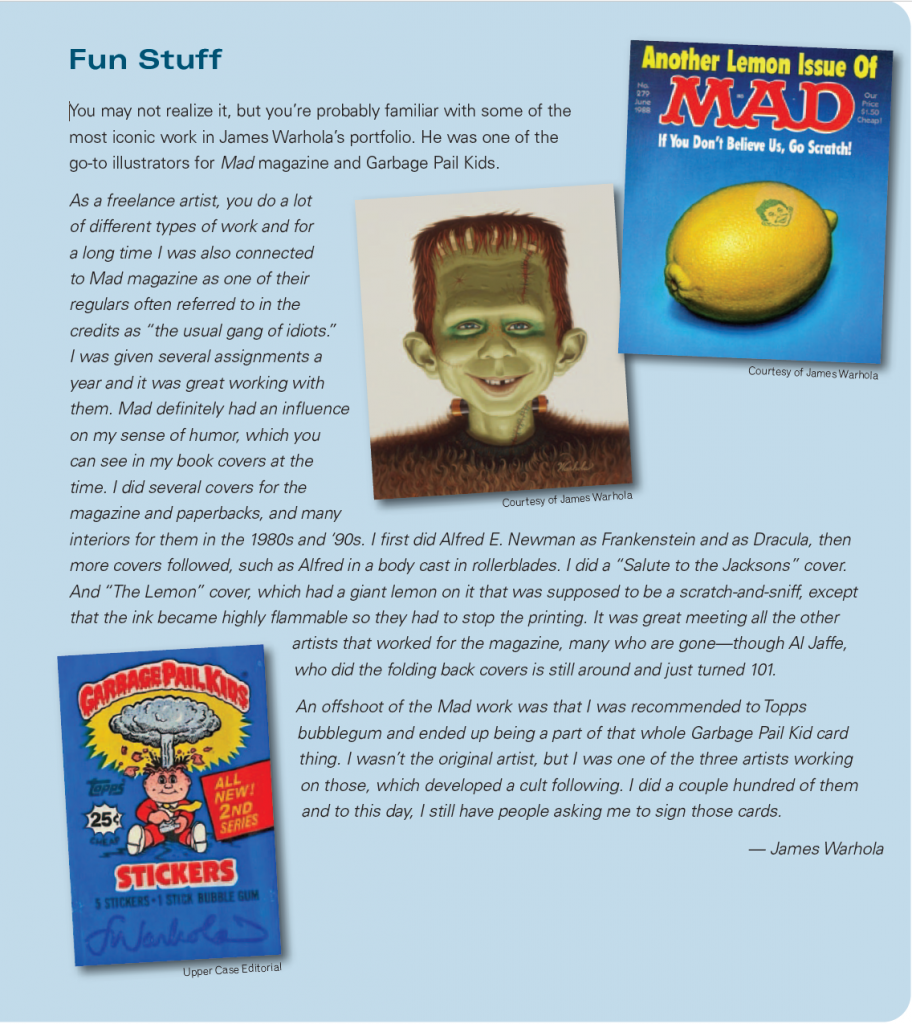

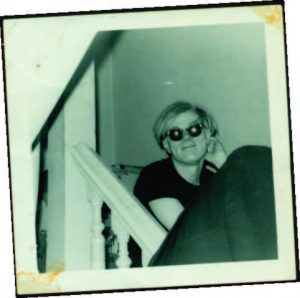

Andy Warhol was a lot of things to a lot of people. To artist James Warhola, he was Uncle Andy. During a career that stretches back four decades, Warhola has been celebrated for his technical mastery, fertile imagination and sly sense of humor. Are we seeing a pattern here? After creating hundreds of covers for popular science fiction titles, he wrote and illustrated a best-selling children’s book about his boyhood visits to his uncle’s New York City studio and home. EDGE editor Mark Stewart sat down with Warhola to find out more about this unique window into the life of a Pop Art icon, and how James found his own niche in the “family business.”

EDGE: What are your memories of the early interactions you had with Andy?

JW: When I came along in 1955, my uncle was already working in New York as a commercial illustrator. I knew him as kind of a bit of an odd creature, living outside the family, who was not like my working-class relatives employed in steel mills and scrap yards around Pittsburgh. His mother, Julia, my grandmother, raised Andy and his brothers in Pittsburgh, but she moved with him up to New York. It was a disconnected situation for me because I couldn’t picture my father having this younger brother who was a very creative, unique individual—into all sorts of great things. I aspired at a young age to be an artist like my uncle. He was illustrating all sorts of things—shoes, appliances, record albums. It just seemed like a wonderful world to get into.

EDGE: Were your parents behind this plan?

JW: Knowing that he made a really good living at it, they were very supportive. Ultimately, I ended up going to Carnegie Mellon University—which used to to be called the Carnegie Institute of Technology, which is where my uncle went. I had a few of the professors that had taught him and they always had “Andy stories.” Apparently, he left quite an impression on his teachers and fellow classmates in college.

EDGE: This was in 1946, right after the war ended, and all these GIs were coming back to school. I’m trying to picture a class full of soldiers and teenage Andy Warhol, and it’s not easy.

JW: Yeah, he was a youngster next to his classmates. And yes, exactly, that first year was difficult for him. He almost was kicked out of school because they had to make room for these vets who were coming back from the war on the GI Bill. Andy was maybe three or four years younger. But he made up a few of his courses during that summer and they allowed him to stay. He ultimately became kind of a star amongst his fellow students. I’ve had the good fortune of talking to many of his classmates and they were just in awe of his ability. He was a little awkward and shy, but his work spoke for itself.

EDGE: Earlier, you mentioned shoes. I covered the footwear industry in my early days as a journalist and people would always say to me, “You know, Andy Warhol, started in this business.” He must have made an impression on the people in that business, too.

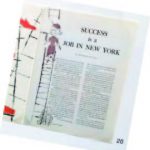

JW: Oh, yes. In fact, his very first job was for Glamour magazine—a story titled “Success is a Job in New York” At the beginning of the article, there were a few shoes that needed to be illustrated which he did in a very realistic way. But in the rest of the article his illustrations were kind of whimsical, with these types of young women climbing ladders.

EDGE: What was different about his commercial work?

Courtesy of James Warhola

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: He had this technique which he started in college, called the “blotted ink technique.” He would basically use pen and ink on paper and then hinge another piece of paper to it that he would blot with. The blotted image that had an irregular line became the final art.

Art directors just loved that spontaneous style. It was almost like it was printed, but quite accidental at times, and he got a reputation for it. Lo and behold, one of the upscale women’s shoe companies called I. Miller, which had several stores in the city, contracted with him to do their New York Times advertising. He was able to represent shoes, which were basically boring if they were photographed, in a way that made them look very sleek and wonderful in the advertising. I always felt that the 10 or 12 years he spent in the commercial world was the ultimate graduate program. It was a really great experience. He learned how to work with people, a lot of whom were great art directors and designers. He learned a lot about color, about promotion and how to be noticed amongst the crowd. He caught on really quickly. I never heard of any art director or designer that did not like working with my uncle. A lot of times, he would come in with not just one illustration, but with three or four for them to pick from, which was kind of unheard of at that time. Whether people realized it or not, he was elevating the everyday to the mundane.

EDGE: It sounds like it prepared him well for what was on the horizon.

JW: Yes, I guess it was his training ground for that approach to his art. He was perfectly groomed to be one of the top pop artists of the day. There were several—Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist—quite a group that started all about the same time in the early 1960s. They were all working in the same vein, pushing imagery of the popular culture of the time. But my uncle was the one as I said, perfectly groomed to know what he was doing. He was truly plugged into that world.

EDGE: What did Andy’s rise to fame in the early 1960s look like through the eyes of a child?

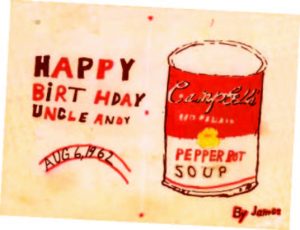

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: I was five or six years old when he moved with Julia from his rented apartment on 35th Street to a beautiful townhouse uptown on 89th and Lexington. It had a lot more room and, at that point, he started experimenting with doing fine art canvases that were related to his commercial product drawings—only more experimental, more spontaneous—imagery of refrigerators, typewriters, windows, telephones and canned fruit. In the beginning, they were kind of loose and drippy. He thought that being expressionistic was making it more artistic. These were his early “pre-pop” paintings that he thought was the direction to go. At some point, he shifted to doing them more cleanly—somebody actually recommended that the drippiness wasn’t necessary—but the idea was still to use the images from advertising in his art. So then, like in 1962, he started doing these clean images of soup cans, which were hand-painted; he hadn’t quite discovered the silkscreening process yet. I didn’t quite understand where he was going with it. It was different. The images were blown up on the canvas using an opaque projector. I remember as a boy his using that projector, which I inherited and used in my field when I was going into illustration. It was soon after that he discovered that silkscreening images was better, so there at his townhouse he experimented doing multiples.

EDGE: What do you recall about of your time with him on your New York visits?

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: I used to love watching him draw. It was like magic. His hand would dance around the paper. He practiced using a ballpoint pen and he had these 16” x 20” pads and he would just fill them up with drawings. I think it was his way of keeping his talent, keeping his hand going. But he did thousands of “practice” drawings. They’re all wonderful and a lot of people who know him from his silkscreens don’t realize that he actually was a really incredible draftsman. I remember wanting to be like him in that way, being a good draftsman. When my siblings and I would visit from Pittsburgh, we often saw him paint. He’d let us watch and sometimes he would give us little chores to do while he was painting. I thought it was quite an exciting time. I mean, of course, he was special to us. He wasn’t really famous at that point, but he was famous to us. He lived in this strange place that was so different and we were all captivated by him.

EDGE: So I have to ask…are there silkscreens hanging in museums that you had a helping hand in?

JW: We did help him by holding the frame so he could pull the paint through. That was when he was doing the smaller silk screens, for instance the Coke bottles, the Fragile labels, the little ones of Elvis and Natalie Wood, in his small studio room. So, yeah, those early silkscreens were done at home. In fact, the early Marilyn Monroes are the ones that have “mistakes.” Some of them have a lot of ink. Some of them have hardly any. Silkscreening is not an easy process. The ink very often has a powerful smell to it and it dries really quickly. So you have to clean the screen out continuously, otherwise the image gets lighter and lighter. If you look at the early silkscreens he did in 1962, those are full of mistakes. To me, my favorite works of art that my uncle did are those early silkscreens of ’62, because I can just picture him working at home doing the best he can.

EDGE: When did he start working in a studio that was separate from the townhouse?

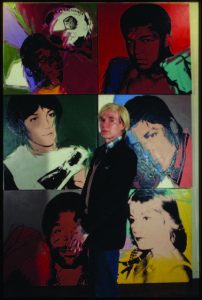

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: He wanted to do large silkscreens of Liz Taylor and Elvis Presley and he couldn’t do them at home, because they required much more space so in 1963 he had to get an outside studio and an assistant. Nathan Gluck continued to help him with his illustration assignments at his home studio and Gerard Malanga was hired to assist with the large silk screening at the firehouse studio he rented two blocks away.

EDGE: In what ways do you think you were inspired or influenced by your uncle?

JW: I was inspired by the fact he was an artist and he was an illustrator. But as far as being a fine artist, I didn’t quite make it to that point. I was too much of a traditionalist, I think, and because of my upbringing, I had a totally different viewpoint. I was part of the television generation starting in the 1950s and ’60s. I didn’t quite understand the creative avant garde aspects of what my uncle was doing. So he didn’t really have that great of an effect on me, although he did support what I was going through. When I told him I was going to study at Carnegie-Mellon, he thought it was great idea.

EDGE: Did he offer any advice at that point?

JW: He thought that I probably should go more into photography than illustration. He believed that illustration was a dying art in the 1970s—that they were using much more photography. And he was right about that. The Golden Age of illustration from the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s was kind of going bye-bye, and they were using a lot more photography. So the available work for an illustrator was more in book publishing, which is where I ended up.

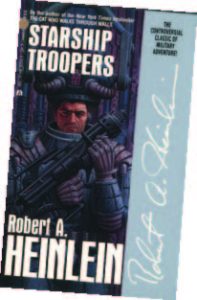

EDGE: You were one of the most prolific sci-fi cover artists of your era. How did you get into that genre?

JW: I had this interest in science fiction and fantasy, being that I grew up with comic books and watching science fiction movies. So I had an idea that I’d go into illustrating books that were science fiction-oriented. And that’s what I did for many years. I illustrated a lot of well-known authors and did three or four hundred covers. I loved reading the books and envisioning some important part of the story to put on the cover. Then the opportunity came up to do children’s books and that kind of opened up a whole new area for me. Instead of illustrating just the one cover that represents a whole book, I would illustrate the entire story, which is a lot more satisfying.

EDGE: What was the actual process for creating a cover that sells?

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: I would get a big, thick raw manuscript. I’d read it over a few times, pull out details and come up with some thumbnail sketches. I would show those to the art director, the art director would go to the editor, the editors would discuss it, and then they’d get back to me with suggestions—or they might like one that’s going in the right direction and give me the go-ahead. I never spoke to the writers. In fact, the process was always that the editors and art directors purposely kept the writer and the artist separate. So we would start with sketches of multiple cover ideas and then I would do one they liked in color. I kept to an organized process so I wouldn’t have to do any kind of corrections in the final art. Since I worked in oil paints, it wasn’t an easy thing to correct. Of course, you wouldn’t want to give away any details in the story that would ruin the ending, but you wanted to pick a climactic moment. I mean, if there was a dragon in the story, you’ve got to use that dragon somehow—also, personally, I loved doing dragons.

EDGE: What set you apart from other artists in the sci-fi/fantasy world?

JW: Over the years, publishers discovered that I was really good at doing covers that had a sense of humor. If there was some kind of humorous aspect to the story I could capture, I loved that aspect. I kind of got a reputation for that. I used to do these books by Spider Robinson who wrote stories about a futuristic bar room with all these crazy alien creatures in them. So, I usually did these scenes for the covers.

EDGE: Did any of your covers become movies posters?

JW: No, not specifically. When a book is turned into a movie, they’ll usually eliminate the illustrated cover and use a photograph from the movie. Like, I did Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers and sure enough they came out with the movie, so they republished the book with the lead actor on the cover, my original illustration was kind of jettisoned. I did do the very first cover for William Gibson’s Neuromancer, which became a groundbreaking science fiction book. It delved into the whole computer world and was the first of its kind, known as Cyberpunk. They only published a few thousand copies at first, but then it ended up winning the Nebula Award that year in 1985, which is the big science fiction award. It was never made into a movie, though it was attempted.

Courtesy of James Warhola

EDGE: I recently unearthed some articles I wrote in the 1980s and thought, “Wow I might actually hire this guy!” Do you look back at the early work you did coming out of Carnegie-Mellon and the Art Students League in New York and feel positive about it?

JW: I’m quite impressed with it, actually, because the detail and amount of time I would put into my paintings was so beyond what I’d have the patience for today. I guess it’s just the gradual evolution of an artist who becomes a little more impressionistic. But I quite often marvel at the amount of detail that I used to work with, and the patience. I tell you, that’s quite a gift at a younger age. It’s hard to recapture that.

EDGE: It’s the energy of youth…

JW: Yes…and sticking with a painting! I mean, I can remember sitting at an easel, probably for 16 hours straight, taking a quick break for a bite to eat, and just plowing through all the work that would be required to paint every little creature in those covers. And then, quite often, you’d pick something out and have to repair it or repaint it.

EDGE: As you mentioned, you’ve done a lot of work in children’s books, as both an illustrator and a writer. How did that come about?

JW: Initially, an art director came to me with a manuscript, The Pumpkinville Mystery and said, Try this.

Of course, the whole project didn’t pay as much as a book cover—it was a lot less money and a lot more work, so I kind of resisted at first. But then I did give it a try and liked the result—and everybody else that I did it for liked it, too. So they continued to give me book projects to do. Mapping out a whole children’s book is fun because you’re actually showing the plot and the climax as you come to the end. I have to say, it’s one of the most creative areas that an illustrator can work in. There’s not one type of accepted style, like in the paperback market, where you had to be kind of photographic and couldn’t be cartoony. But in the children’s book area, you can be anybody you want. I like that flexibility. At some point, I was encouraged to try to write my own stories, because if you write and illustrate your own story, you get the full royalty if the book sells well.

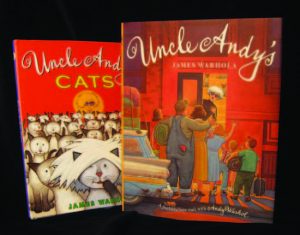

EDGE: Which brings us to your Uncle Andy books.

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: The first book that I authored as well as illustrated was Uncle Andy’s: A Faabbulous Visit with Andy Warhol. It was about my visits with my family to my uncle’s and grandmother’s house in New York City at a time when he was producing all that early pop art. It was also a window into my uncle’s homelife. Most people didn’t realize that he lived with his mother and had two brothers with large families that would occasionally show up unannounced. It was kind of fun to enlighten the world on his personal life. At one point, my uncle had a lot of cats. They were all Siamese cats and they paraded throughout the house for several years. Everybody saw the cats in the first book and they said, Oh, you gotta do a book about the cats! So I did Uncle Andy’s Cats, which was very enjoyable.

EDGE: Do you think of yourself as coming from an “art” family?

JW: Yes, I do in a way. From an early age, thanks to my uncle Andy, I felt that I that I was a part of the art world. And now my daughter, who’s 25, graduated a few years ago from Cooper Union and she has this obsession with being an artist herself. She doesn’t want to be an illustrator—she saw the pain and agony that I’d go through with my strange books—so maybe the fine art aspect skipped my generation. But, yeah, I definitely feel I’m part of an art family. And I think that my grandmother, Julia, played a significant part in that. She felt there was an artistic aspect to everything—a beauty, whether it’s visual or just an idea. She connected with her kids, who then connected to us. My grandmother was a very creative person. She liked to sing and dance, she did all kinds of art and sewing projects. She brought this belief directly from the “old country,” the Carpathian Mountains in eastern Slovakia, that you could create something different from anything. She emphasized this to her grandkids and I think that’s what I’ve been inspired by. She was a very unique individual who was the one person most important in nurturing my uncle Andy’s creative abilities.

Editor’s Note: In the off-the-record part of their conversation, Mark Stewart and James Warhola found they had something in common beyond the children’s books each has written. In the late-1970s, both studied at The Art Students League on 57th Street in New York.