Toy Story 0.5 (aka Surviving the 1960s)

Once upon a time, in a foreign country called the 1960s, there were no au pairs, soccer moms or helicopter parents. City kids rode public buses to school and back. In the suburbs, children roamed neighborhoods like packs of feral animals. Uncle Frank might slip 12-year-old nieces and nephews fireworks and cigarettes and a gulp of his beer every now and then—and make them promise not to tell mom and dad (or Aunt Shirley). Granddad would take you out in his Pontiac Bonneville at dawn on Sunday morning and teach you to drive on the Pulaski Skyway and the New Jersey Turnpike. Believe it or not.

Upper Case Editorial Services

If, like me, you were born in the United States between 1954 and 1964, you belong to an exclusive demographic: The Late Baby Boomers. We were born smack-dab in the middle of what economists have dubbed The Thirty Glorious Years, an epoch of prosperity and abundance unparalleled in human history. We were the progeny of the can-do New Frontier. We were expected to grow up fast and, in large part, do it on our own. More and more of us were children of divorce, with two or more working parents. The term invented for us was latchkey kids. A close friend who’s a bit older and wiser observed that a lot of us suffered from benign neglect. He maintains that we didn’t get enough time with our folks, who were always working. And that they couldn’t wait until we were old enough to start working, too.

www.istockphoto.com

So many of the toys produced and marketed to us in the 1960s, and that our parents bought for us, are looked upon a half-century later with horror and disbelief. If you’re a Late Baby Boomer, however, you also harbor a certain nostalgia for all those hot, sharp and toxic playthings. I think this is because they reflected the cultural philosophy of our parents. Life is full of risks, kid—here’s some dangerous stuff to get you used to taking them. And don’t come crying to us unless you need stitches.

Mattel, Inc.

CALIFORNIA DREAMIN’

I was born in San Francisco in 1960 and was a toddler in Santa Monica. My parents relocated back to Manhattan before I turned three. On weekends, I’d kick around my grandfather’s car dealership in Jersey City. In March of 1968, my mom put me on an American Airlines flight from JFK to LAX, alone, to meet up with my copywriter dad, who was shooting a series of KOOL cigarette ads in Southern California. The stewardesses pampered me like a lost puppy.

For an eight-year-old kid who only knew the gray, gritty streets and harsh winters of New York, Los Angeles in 1968 was like paradise. Perfect concrete streets, fantastic googie architecture, Hollywood studio backlots, dayglo and hippies and surf music and Kustom Kars. And the Valhalla of all 1960s kids: the Magic Kingdom of Disneyland in Anaheim. On the way to D-Land, on the I-5 Golden State Freeway, we passed through Hawthorne. Right there along the side of the freeway was Disneyland’s not-so-distant cousin, the Magic Factory of Mattel Toys, where just about everything cool—from Hot Wheels to Creepy Crawlers—were actually made.

In San Gabriel, five minutes off the I-10 Santa Monica Freeway, just about everything else that was cool was made at the Wham-O factory: Hula Hoops, Frisbees, Super Balls, Slip and Slides, Instant Elastic Bubble Plastic, Silly String and Silly Slime. If it could be made from some potentially toxic new plastic polymer, you could be sure that Wham-O would serve it up.

Think about it. Pretty much all of today’s extreme sports were birthed by us Late Baby Boomers. We built jumps for our Sting-Rays and Tarzan swings at lake shores. We snuck into neighbors’ backyards to skateboard in their empty swimming pools. Cowboys & Indians seemed quaint and outdated to us. We played war…how much more “extreme” can you get?

Not that we had many options. Growing up in the 1960s, there were no video games, just a black & white screen (only the seriously affluent had color TVs) with a handful of channels that actually ran children’s programming. Most of the shows I watched had product tie-ins with toy companies like Marx, Transogram, Mattel, Ideal and Topper. Most of the action toys—particularly for boys—launched projectiles like rockets or grenades, using springs or water/air pressure. A few in particular that stick in my head are the Fireball XL5 Space City Playset, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Napoleon Solo gun, and the James Bond 007 Attaché Case, which shot a hard plastic bullet with the press of a hidden button in the handle.

I grew up a Junior Mad Man. My dad was an advertising copywriter, my mom an account executive and stepdad an art director. Basically, I was hardwired to consume from the cradle. Television was the gift that never stopped giving. It brought the money into the house, and then showed what you could exchange for it. For me, it was invariably the latest dangerous, worthless plastic piece of junk as seen on TV. Surviving examples are still dangerous and toxic, but the ones in mint-condition are far from worthless. Spend five minutes on eBay and you’ll see.

It occurs to me that the much-maligned Helicopter Parent might be the indirect product of these toys. Maybe these are the boys who were bludgeoned or terrorized or used as guinea pigs by their older siblings. Or the girls who scorched themselves cooking cupcakes with 200-watt lightbulbs. In one generation, the protection pendulum swung from one extreme to the other.

I look back at the halcyon days of irresponsible parenting and no longer ask What were they thinking? I’m halfway through my 50s now and I get it. All is forgiven. The folks who designed and marketed the toys we played with, however, are another matter entirely. I don’t think I’ll ever understand how some of these products found their way on to store shelves. Here then are my Unlucky 13:

I NEVER INHALED

Which is a good thing, because the Gilbert Glass Blowing Kit—manufactured until the early 1960s and available at garage sales for another decade—was permanent lung damage waiting to happen. Lest you forget, molten glass has a temperature of 1000º F. A sure litmus test to see if your parents were cheapskates (or simply out to maim you) was whether or not they’d cough up the additional coin for goggles, a pair of welder’s gloves, and an asbestos table board. Because, you guessed it, safety equipment was “sold separately.”

Upper Case Editorial Services

BIG BANG

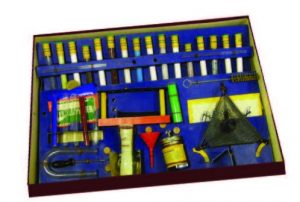

Introduced in the 1940s and manufactured until the early 1970s, Chemistry Sets put the boom in the Baby Boom. Blowing yourself up or poisoning yourself was no problem thanks to entry-level basics Potassium Permanganate and Ammonium Nitrate, Tannic Acid and Sodium Ferrocyanide. Bomb- and poison-making made simple and fun! Refills available. Some of the most popular and dramatic things a kid could do with a deluxe set was to perform magic tricks, like turning water (aqueous solution of sodium carbonate and bicarbonate) into wine (adding phenolphthalein), then into milk (adding barium chloride), and then into beer (adding potassium dichromate and hydrochloric acid). The grand finale? Persuading your “assistant” (younger sibling, idiot neighbor) to drink it.

BURN NOTICE

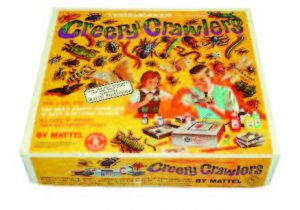

Why squander precious nickels and dimes buying rubber bugs out of gumball machines when you could make your own? The economics of Mattel’s

Mattel, Inc.

Creepy Crawlers seemed obvious to anyone with a first-grade education. And that’s about how old kids were when their parents handed them a box containing a 300ºF hot plate, cast metal molds and a semi-liquid “non-toxic” substance in plastic squeeze bottles that everyone called “goop.” Creepy Crawlers hit the market in 1965 and were incredibly popular. Unfortunately, they weren’t edible. So in 1968, Mattel unveiled Incredible Edibles—featuring the same equipment along with semi-liquid candy called Gobble-Degoop in six colors and flavors: root beer, cherry, licorice, butterscotch, cinnamon, and mint. My friends and I got some very nasty burns and blisters from these child scar-makers. We’d become impatient for the bugs to finish cooking solid, and get splattered with super-hot molten plastic and gummy sauce trying to pry them out of the burning-hot molds with tweezers and sewing needles. On the plus side, visiting the emergency room was very educational.

SHOP TIL YOU DROP

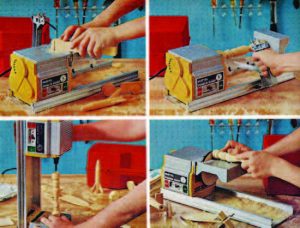

Sand off your fingerprints! Lose a pinky! Drill-press the cat! The Mattel

Mattel, Inc.

Power Shop, introduced in 1964, offered dozens of possible projects and hours of fun. All of the big, noisy machines those lucky big kids were allowed to use in junior high were now within your seven-year-old grasp (at least until you started severing tendons).

HONORABLE MENTION

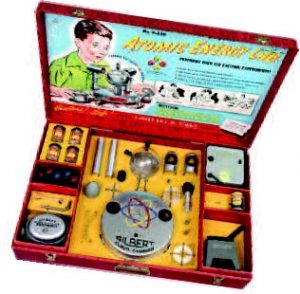

For two years in the early 1950s, parents could purchase at the then-astronomical cost of $50 the

A.C. Gilbert Company

Gilbert Model #U-238 Atomic Energy Lab. The sell copy says it all:

- Most modern scientific set ever created!

- See paths of alpha particles speeding at 12,000 miles per second!

- Watch actual atomic disintegration—right before your eyes!

- Prospect for Uranium with Geiger-Mueller Counter!

- 10,000 Dollar Reward: That’s what the United States Government will pay to anyone who discovers deposits of Uranium ore!

- Full details in the book Prospecting for Uranium, packed with this Atomic Energy Lab.

- Includes: Geiger-Muller Counter, Wilson Cloud Chamber, Spinthariscope, Electroscope, Nuclear Spheres, Alpha Beta and Gamma radiation sources, radioactive ores.

- Three illustrated books: Prospecting for Uranium, How Dagwood Splits the Atom, Gilbert Atomic Energy Instruction Book

- All Samples of Radioactive Materials are Completely Harmless!

I can’t imagine why this was pulled off the market. By the way, if you want a mint-condition original today, get out your gold coin. They can sell for thousands at auction.

DIGITAL DIVIDE

Say what you will about Mattel’s electric-powered toys. At least they were certified by Underwriters’ Laboratories. No such luck with Jig Saw Junior, which hit the market in 1958 courtesy of Burgess Industries, with this bit of marketing gold: “It will vibrate well enough to cut balsa or other thin soft woods without taking off your child’s finger.” You can practically hear Dan Aykroyd’s sleazy Irwin Mainway character pitching this product on SNL between Bag o’ Glass and Johnny Human Torch.

BLAST FROM THE PAST

Water Rockets were our gateway drug to the Space Race. For a couple of bucks, every child could do his or her part to beat the Russkies to the moon—and get a refreshing, explosive splash of water on a hot summer day. So let’s do the Newtonian calculus: Two pounds of air-pressure water sealed in hard plastic, accelerating to a velocity of 40 miles per hour within a few yards. Just what a kid needs to crack the windshield of the family car. Or dent the skull of his nerd cousin Elaine.

Transogram Company, Inc.

WEARABLE WHIPLASH

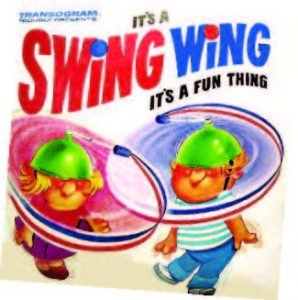

The

Swing Wing, introduced in 1965, was one of those toys that made absolutely no sense, but how could you not beg your parents for it after seeing those head-twirling kids on the commercial? It was a plastic chin-strapped beanie, with a long weighted cord attached to a pivot on top. It was meant to be a cranium-mounted spin-off of the Hula Hoop. Which translated to permanent neck vertebrae damage and—for the accomplished Swing-Winger—potential paralysis. From Transogram…Where the FUN comes from!

Photo by Santishek

STRING THEORY

The idea was elegant in its stupidity. Klik-Klaks were two hard-plastic spheres attached by thin cords to a central ring, which slipped over your finger. Move your hand up and down at just the right speed, and they crashed together at 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock again and again and again. They were outlawed in schools for noise and safety reasons, but that just made them more alluring, and in the late-60s companies rushed cheaply made competing versions to market with no regard for quality. This led to two basic outcomes: String failure, leading to property damage, or a shattered ball, leading to eye damage.

SLIPPERY SLOPE

Wham-O introduced the Slip and Slide in 1961as the backyard progenitor to the waterslide theme park. It was nothing more than a garden hose attached to a long strip of slick vinyl. Millions were sold before anyone gave a second thought to safety. If you broke a toe on one of the stakes that secured it to the lawn or caught a major raspberry on the driveway because you slid off the end, well…that was your problem. Kids who limped away from these injuries were the lucky ones. Adults who found this toy irresistible relearned much of what they had forgotten from physics class, like “a body in motion tends to stay in motion” (Newton again) even when you run out of Slip and Slide. Eventually, words like “spinal cord injury” and “death” were included in the instruction manual’s safety warnings. A handicapped access icon should have been added, too.

Louis Marx & Co.

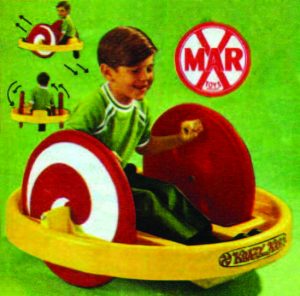

NO BRAKES NO STEERING NO PROBLEM

Introduced in 1968, the Krazy Kar from Marx was an ill-conceived kiddy car compounded by a near-total absence of control. Kids sat in a circular plastic frame and propelled themselves using two oversized wheels with handles. Two pivoting shopping-cart wheels at the front and rear ensured kraziness. The children pictured on the packaging seemed blissfully unaware of their fate. Perhaps they lived in a hilltop subdivision or at the end of a steep driveway. Its more-than-passing resemblance to a “krazy” wheelchair should have been a tip-off to parents. And yet, the Krazy Kar has endured, careening back into stores during the 1990s to inure a whole new generation of kids.

TRIGGER HAPPY

The category of Projectile-Firing Toy Guns could fill an entire issue of this magazine. Their heyday was roughly 1955 to 1970, and they ranged from easily concealed pistols to hefty weapons of mass destruction. As a boy, I owned the Zebra Pistol, which fired small rubber pellets, and the Star Trek Disc Pistol, which zipped out nickel-sized, multicolored hard-plastic disks. (An admission here and long-overdue apology: In the hands of an expert, these pellets and discs could be ricocheted off plate glass with an astonishing degree of accuracy, tailor-made for terrorizing the East Side society matrons and their tiny dogs out window shopping on Madison Avenue.) Meanwhile, it was the big guns—like

Photo by Mike Evangelist

Johnny Seven OMA and Johnny Eagle Magumba big- game rifle—that transformed innocent child’s play into a Photo by Mike Evangelist magnificently destructive experience. Hummel and Staffordshire figurines, proudly displayed Royal Doulton china, or really anything perched on a mantle or étagère, made for an irresistible target—at, I might add, an impressively long range. Finally, for those of us who couldn’t wait to get to Vietnam but were a dozen years too young, there was the ultimate in heavy artillery: the REMCO Marine Raider Bazooka. It fired a hollow blue hard-plastic two-inch “USMC” bazooka round with a muzzle velocity of at least 60 miles per hour. At point-blank range, well, Farewell, My Lovely—eyesight or baby teeth, that is.

A MIGHTY WIND

A MIGHTY WIND

For parents who had absolutely no common sense, the go-to toy had to be the Air Cannon. As their names imply, the Agent Zero-M Sonic Blaster and Wham-O Air Blaster, both introduced in the mid-60s, were a blast. Kurt Russell proved it to us in an early commercial, which you can easily find on YouTube. The wisdom of handing a small child one of these products is best illustrated in a black & white snapshot of my oldest friend, who was photographed shouldering an Agent Zero-M. He was probably blowing a squirrel out of a tree. The photo made him something of an internet sensation. If you wanted to give your enemy a sporting chance, you could opt for the handheld Wham-O blaster. Both toys were meant to blow down cardboard targets with a massive puff of air, but clever kids soon figured out that just about anything—from ping-pong balls to prune juice—could be loaded into either one and fired “to great effect” during a grownup dinner party.

INCOMING!

No story on dangerous toys would be complete without a few words about Lawn Darts. The name itself tells any sane person all they need to know. Seriously, is there any lawn in the world that is improved Irwin Sports by the introduction of

darts? Essentially, these were hard-to-see mini-javelins made for people with dubious athletic skill and depth perception—never a good combination. There’s an old saying that “close” only counts in horseshoes and hand grenades. In lawn darts, getting close to your target often precipitated a trip to the hospital.

Editor’s Note: Luke Sacher is a documentary filmmaker and an avid collector of antique and classic toys—an expensive habit he picked up from his mom, who amassed a spectacular collection. Luke authored Apocalypse Wow for our Good Earth Issue, a compendium of noteworthy end-of-the-world movies. Check it out at edgemagonline.com.