In the trenches with New Jersey’s heroic food producers.

By Andy Clurfeld

Morning has broken, and I’m rough-chopping Terhune’s Winesaps, an apple that’s a little more tart than sweet, and tossing the cubes into a small stovetop pot moistened by melted Valley Shepherd butter. I add a couple of cups of Morganics oats, a dash of cinnamon, and stir, coating the oats and apples with the spice and butter. A minute later, I add water to cover, pump up the heat till the liquid bubbles, then turn down the flame and cook my oatmeal, stirring now and again, for a handful of minutes until the oats and apples are soft. Should I add a splash of maple syrup from Sweet Sourland Farms? Honey? Why not a tad bit of both? I lower the heat under my pot of oatmeal to the barest of simmers and grab myself a bowl and a spoon.

The skies are cloudy and the air outside damp, but my morning is about to take a turn for pure bright: Morganics Family Farm oatmeal is the ideal breakfast, the jump-starter of any day at all, be it crammed and tense or lazy with time for dreaming. Scott and Alison Morgan’s farm in Hillsborough is where the couple oversee operations that result in the freshest possible grains—grains grown in sustainable, eco-responsible fashion. When you eat fresh, sun-dried grains, “your body will reap the benefits,” the Morgans say I agree. My breakfast of oatmeal made with Morganics oats, Valley Shepherd butter from the creamery in Long Valley, apples from Terhune Farms in Mercer County, honey from Top of the Mountain in Wantage, and maple syrup from Sweet Sourland in Hopewell, revs up my mind, body and heart. I am inspired, fueled and gratified to be eating an all-star New Jersey meal.

It’s what I most love to do. Once upon a not-so-long-time-ago, it was much harder to do. But today there are myriad and many farmers and food artisans who are the Garden State’s true unsung heroes, people who are plying the various soils and waters of a peninsula packed with some 8.9 million people and offering an array of foods that have not traveled thousands of miles over the course of weeks before transfer to supermarket shelves. These heroes increasingly farm and produce fresh foods year-round, employing new techniques and technologies to serve forth a bounty with an impeccable pedigree: New Jersey, the Garden State. Jersey-born, Jersey-bred, Jersey-proud.

River Bend Farm/Gladstone Valley Pasture Poultry • Far Hills

Dakota and Duke are loving life. They’re doing their job, these 4-year-old guardians of livestock bred in the Italian Alps and best known by their breed name, Maremma. Huge, hairy and armed with a ferocious bark, the dogs seem to be everywhere they need to be in order to protect Corné Vogelaar’s chickens from harm that may come by air or land. “Right now, they’re guarding the layers,” Corné says. “They guard against the aerial predators and they guard against the fox and the coyotes. It’s all instinct. They are not vicious; their weapon is their alertness and their bark.”

They work where the girls are, the egg-layers, the turkeys, the broilers—those Cornish crosses that are the pasture-raised chickens sold under the Gladstone Valley Pasture Poultry label. A sibling enterprise to River Bend Farm, headquartered in Far Hills, Gladstone Valley chickens are the American equivalent to the Bresse chicken in France, the anointed “queen of poultry, poultry of kings.”

They work where the girls are, the egg-layers, the turkeys, the broilers—those Cornish crosses that are the pasture-raised chickens sold under the Gladstone Valley Pasture Poultry label. A sibling enterprise to River Bend Farm, headquartered in Far Hills, Gladstone Valley chickens are the American equivalent to the Bresse chicken in France, the anointed “queen of poultry, poultry of kings.”

“They’re out on grass and rotated on fresh grass daily,” Corné says, describing the efficiency of the “chicken tractor,” which pulls the chickens’ homey coop to new servings of the good stuff. Dakota and Duke appear to smile as Corné gives them each a good rubbing behind the ears. Then it’s Corné’s turn to smile. He’s been loving life at River Bend Farm since 1996, shortly after he graduated Rutgers with a degree in animal science. Born and raised in Holland, he came with his family to the United States in 1988. Farming was his goal. He spent his first 10 years at River Bend, then all-cattle and all-Angus, improving the species.

“I really love the genetics and the breeding of better cattle,” Corné notes. Slowly, he “started harvesting beef and marketing it. The meat business is now our main business, and we also supply breeding stock to other farmers.” In more recent years, he’s added Berkshire pigs (“the Angus of pork”) and a few Mangalistas as well to his stock. There’s lamb and there are the chickens and there are eggs.

Corné sells to an A-List of restaurants, including the Ryland Inn, Pluckemin Inn and the Harvest Group eateries. “We are fortunate to work with excellent chefs who know how to work nose-to-tail and use everything,” he says. But home cooks also are in the River Bend/Gladstone mix: Along with a self-service egg cart, Corné keeps an on-farm store open for retail sales of frozen beef, chicken, pork and lamb on Friday afternoons and Saturday mornings. He sells at the in-season Bedminster Farmers’ Market.

As manager of the privately owned farm, Corné tends to the needs of a sizable span of animals. But he doesn’t do it alone. There are a couple additional full-time employees; his two oldest sons also work on day-to-day operations. Corné and his wife, Dawn, have eight children, six boys and two girls ranging in age from a baby born this past January to a 21-year-old whose welding skills are useful on the farm. Corné invites me into one of the cattle pastures. “Come meet Clover,” he says. “She’s more of a pet.” He maneuvers the sweet bovine in my direction and nods when I pet her. I’m loving life, too.

Hillcrest Orchard & Dairy/ Jersey Girl Cheese • Branchville

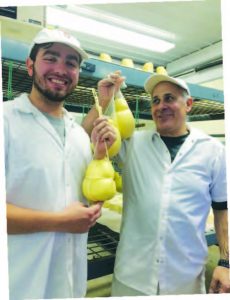

Sal Pisani is scooping ricotta into baskets set atop trays, allowing the fresh, warm cheese to drain, and talking in Italian to Raffaelle “Ralph” Saporito, who is both balling up and braiding batches of mozzarella. Sal and Ralph talk cheese in Italian almost every day, a language that bridges the near-35-year difference in their ages. Ralph was born in Raritan; at age 3, his family returned to Naples, Italy. A revered cheesemaker in Italy, he returned to the United States to teach Sal the art and craft of making classic Italian cheeses. “I’m an apprentice,” says Sal, 27, “and Ralph is my teacher.”

Professor in a doctoral program is more like it. Sal Pisani grew up under the tutelage of his father Rocco, who was born and reared in Calabria, Italy, but moved to the U.S. at 21, settling in Morris County. There, on threeacres, the Pisani family created their own Little Italy. “My father brought with him the traditions he picked up from his mother,” Sal says. “Dad would make cheese, cure meats. Every September, we’d make tomato sauce. It was all about food, when I was growing up, homesteading, not selling what we made.” There was a vegetable garden, animals – “chickens, goats, a horse, sheep, a peacock and an alpaca, but never more than 15 animals”—and the constant rhythm of time at the table with family and friends.

Professor in a doctoral program is more like it. Sal Pisani grew up under the tutelage of his father Rocco, who was born and reared in Calabria, Italy, but moved to the U.S. at 21, settling in Morris County. There, on threeacres, the Pisani family created their own Little Italy. “My father brought with him the traditions he picked up from his mother,” Sal says. “Dad would make cheese, cure meats. Every September, we’d make tomato sauce. It was all about food, when I was growing up, homesteading, not selling what we made.” There was a vegetable garden, animals – “chickens, goats, a horse, sheep, a peacock and an alpaca, but never more than 15 animals”—and the constant rhythm of time at the table with family and friends.

Sal graduated Monmouth University in 2014 and returned home. Cheesemaking was his passion; it drew him in as a career when he learned of a buffalo farm in need of someone to make the herd’s milk into cheese. After that ended, Sal found a new home at Hillcrest, an apple orchard and dairy in Branchville, Sussex County, owned and operated by farmer Jimmy Cuneo. His prize Jersey cows, which yield creamy, high-fat, high-protein, high-quality milk ideal for making Sal’s favorite cheeses, were waiting for the right partner. “Dairyfarms are closing every day, it seems,” Sal says. To keep going, “Jimmy had decided to outfit and expand to accommodate cheesemaking and retail. We made the jump with him. Ralph decided to come and work with us. It was the best luck to find this opportunity.”

The best luck for consumers, too. Sal’s Jersey Girl cheese line currently includes fresh mozzarella, fresh ricotta, scamorza (a dry, aged mozzarella), primo sale (a fresh basket cheese), cacciocavalo (a sharp-tasting aged cheese) and burrata, and is sold at farmers’ markets in Sparta, Morristown and Holmdel, as well as Saturdays and Sundays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. at the farm’s own store in Branchville.

Back in the cheesemaking room, Ralph Saporito finishes braiding mozzarella and his protege scoops a spoonful of the still-warm ricotta from a basket. Clouds to heaven—that’s what pops into my mind as I taste. Sal smiles. I sample the mozzarella, the scamorza, the cacciocavalo and know I have never, ever tasted better examples of these beloved cheeses. Italy is no longer an ocean away.

Rolling Hills Farm • Delaware Township

Opening bells at New Jersey’s farmers’ markets don’t always ring in the kind of bounty stalwart shoppers crave. May and June aren’t July, August and September, after all. Not so if you come upon the stalls of Rolling Hills Farm. Fresh from the farm in Delaware Township, Hunterdon County, May and June see bushels and baskets of cucumbers, beets, new potatoes, summer squash, snap peas, salad mixes, arugula, carrots, head lettuces, scallions, Swiss chard, broccoli, cauliflower…okay, time to catch your breath. You might lose it again when you see, up close and in person, the heart-of-spring produce grown by Stephanie Spock and John Squicciarino on a scant 1½ acres.

“Thanks to reading the works of Eliot Coleman,” John says, referring to the New Jersey-born revolutionary farmer whose Four Season Farm on Cape Rosier, Maine, does exactly what its name promises, “we farm year-round [using] high tunnels that let us have produce in May.”

“Our customers go insane over our carrots—they’re the sweetest carrots!” adds Stephanie. They grow in theground, in high tunnels, or hoop houses—plastic-covered structures that allow a plant’s roots to take in the nutrients of good soil, all the while being protected from storms and other excesses of the elements. Not that the couple wish to defy seasonality.

“Our customers go insane over our carrots—they’re the sweetest carrots!” adds Stephanie. They grow in theground, in high tunnels, or hoop houses—plastic-covered structures that allow a plant’s roots to take in the nutrients of good soil, all the while being protected from storms and other excesses of the elements. Not that the couple wish to defy seasonality.

“No tomatoes in May,” both say, as John adds: “We recognize the seasons.”

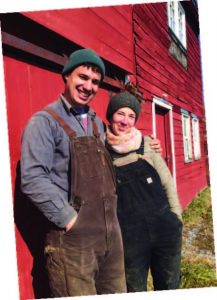

On land leased from members of the Hamill family, of Cherry Grove Farm in Lawrence Township, Stephanie and John grow produce following organic practices and sell at the summertime Asbury Fresh Market as well as at farmers’ markets in Wrightstown and Yardley, PA. Their attraction to farming began while they worked on Brick Farm Tavern’s Double Brook Farm in Hopewell, which has become something of a breeding ground for young farmers as well as chefs learning the lessons of the seasons.

“We were 26 when we started here, in 2014,” John says. “It was stressful in the beginning,” Stephanie adds.

But they were determined. In the depths of winter, Oliver Gubenko’s Harvest Drop, which delivers produce and products from area farms to restaurants and small retail outlets, brings Rolling Hills’ fresh greens for salads and more to chefs. “It’s more work for us, but it’s worth it,” says John. The couple’s year-round, smart-farming practices evens out the workload. Rather than getting burned out by summertime work weeks of 80 to 90 hours, they put in 20 to 25 hours a week in the typically fallow cold-weather months by growing those greens and gearing up for the earlier start that results in bumper crops in May. Summer, as a result, makes for more manageable 50-hour work weeks.

“We do things in winter to make for a bounty in May and June,” John says. Meanwhile, Stephanie is studying nutrition with the goal of having a practice that engages the farm. “It all ties in,” Stephanie says. “What we grow, how we eat, how we feel.”

Chickadee Creek Farm • Pennington

Jess Niederer is standing in a propagation greenhouse on Chickadee Creek Farm, her 25-acre year-round farm in Pennington. Jess looks up, smiles and says, “I got married here, right here, on the Winter Solstice, Dec. 21, 2018.” At 76 feet by 30 feet and cloaked in light, it’s not only a lovely place for a wedding but, in Jess’s words, “the proper size for the planned growth on our farm.”

Jess’s new husband is Kevin Riley, a nurse who works at a federal clinic in Trenton; Kevin’s new wife is a veritable rock star farmer, New Jersey’s answer to Eliot Coleman of Four Season Farm in Maine, and a presence at farmers’ markets both seasonal and year-round in towns all over the state: Princeton, Denville, WestWindsor, Morristown, Rutgers Garden, Hoboken, Summit, Metuchen. Full disclosure: I don’t know how to have dinner at home any more, be it a party or an any-old-night meal, without Chickadee Creek produce at hand. Wherever Jess Niederer sells, I’ll travel to buy. So I’m listening to Jess talk in a near-empty propagation greenhouse and longing to see where the harvested produce that I know is going to the next day’s market is kept. I’m going to buy some to photograph, up close and personal, for this story. And then eat.

Jess grew up in a farming family (fourth-generation, she is), went to Cornell, where she studied ecology and conservation biology, spent a couple of years working at nearby Honey Brook Farm, and is as conversant in the business of farming as she is about how to grow, harvest and market the 56 different crops she grows at Chickadee Creek.

To work it all by the numbers: The Niederer family farm is about 80 acres, 40 of which are tillable and 25 of which—Chickadee Creek—Jess leases from her father. She employs nine people full-time, year-round, and is “trying to get every single one of them up to the $15-an-hour benchmark” well before state requirements kick in. Now in her 10th year running Chickadee Creek, she is 35 years old, has approximately 500 members in her CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) program. When we walk into one of her high tunnels, where gorgeous arugula is grown in the ground all winter, she’s quick to note a $14,000 tractor can work the soil of this 196-foot-by-30-foot structure. The number most on Jess Niederer’s mind, however, is $1 million—that’s the amount Jess needs to buy her farmland from her father. “It would be about $4 million if it wasn’t in the state preserved farmland program,” she says. That would not come with a house—just the land that Jess works to feed the thousands of people in New Jersey who love eating Chickadee produce.

To work it all by the numbers: The Niederer family farm is about 80 acres, 40 of which are tillable and 25 of which—Chickadee Creek—Jess leases from her father. She employs nine people full-time, year-round, and is “trying to get every single one of them up to the $15-an-hour benchmark” well before state requirements kick in. Now in her 10th year running Chickadee Creek, she is 35 years old, has approximately 500 members in her CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) program. When we walk into one of her high tunnels, where gorgeous arugula is grown in the ground all winter, she’s quick to note a $14,000 tractor can work the soil of this 196-foot-by-30-foot structure. The number most on Jess Niederer’s mind, however, is $1 million—that’s the amount Jess needs to buy her farmland from her father. “It would be about $4 million if it wasn’t in the state preserved farmland program,” she says. That would not come with a house—just the land that Jess works to feed the thousands of people in New Jersey who love eating Chickadee produce.

Jess’s business model is based on year-round production, which is good for customers and also good for her staff. If you stop growing, harvesting and selling in the cold months, Jess explains, you effectively lay off your staff. “You can’t keep good people that way,” Jess says. By doing regular net-profit analyses, she is able to determine what’s working (new crops, such as ginger and sweet corn), what needs to be “kicked off” (cauliflower just wasn’t selling), and what’s most profitable (salad greens, head lettuces, flowers, tomatoes, cut greens). She’s keen on farmers’ markets: “They’re time-intensive, but the dollar value is the best.” She doesn’t work with restaurants much. She’s devoted to her CSA members. She keeps the just-harvested produce in temperature-controlled containers until that produce is taken to market.

Ah-ha! On that day, I buy several head lettuces, creamy white Japanese turnips, carrots colored purple, yellow and orange. Two days later, I buy more Chickadee produce at the West Windsor Winter Market. Obsessed? Guilty as charged, and proud of it.

Mishti Chocolates

Mishti Chocolates

What happens when chocolate meets ginger? Or lavender? Or toffee? How about sea salt, pineapple, chile or orange? What if you learn that these chocolate partnerships, as well as the straight-up chocolates, are vegan, organic, non-GMO, soy-free and gluten-free? When the chocolates are by Mishti, it’s about “bringing a smile to every face, one chocolate at a time.” Which is the slogan chocolatier Arpita Kohli wrote when she first started making the coveted chocolates. Because what’s not in Arpita’s chocolates just might be what makes them irresistibly delicious.

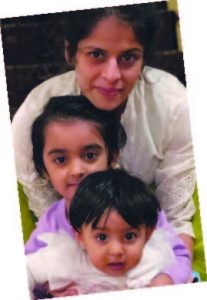

The Scotch Plains resident started making chocolates professionally when she and husband Puneet Girdhar realized their then-baby daughter Mishti had a variety of allergies, including dairy. “We have a healthy household,” says Arpita, a skilled home cook who had been making chocolates since she was a child. “So I started making vegan chocolates.” And it worked. Little Mishti, now 4½, could enjoy chocolates like her mom and dad. Arpita, creative by nature with a career in textiles, kept experimenting and perfecting the chocolate line she named Mishti. She uses 100 percent chocolate; her milk chocolate is made with almond milk and her sourcing meticulous. Her elegant packaging reflects the fundamental simplicity of her recipes and products.

The Scotch Plains resident started making chocolates professionally when she and husband Puneet Girdhar realized their then-baby daughter Mishti had a variety of allergies, including dairy. “We have a healthy household,” says Arpita, a skilled home cook who had been making chocolates since she was a child. “So I started making vegan chocolates.” And it worked. Little Mishti, now 4½, could enjoy chocolates like her mom and dad. Arpita, creative by nature with a career in textiles, kept experimenting and perfecting the chocolate line she named Mishti. She uses 100 percent chocolate; her milk chocolate is made with almond milk and her sourcing meticulous. Her elegant packaging reflects the fundamental simplicity of her recipes and products.

“I don’t want to take all the credit; both my grandmother and mother and all my aunts are excellent cooks. I grew up around great food and wonderful flavors,” Arpita says.

Life’s been busy for the chocolatier. She started the business in 2017 and, in April 2018, gave birth to a second daughter, Seher. “Puneet is my true partner,” she says, praising his support and help in marketing. Indeed, Puneet, Mishti and now Seher are popular regulars at many farmers’ markets, including those in West Windsor, Ramsey and Red Bank, and the chocolates are sold in specialty markets such as Basil Bandwagon in Flemington and Clinton and Dean’s in Basking Ridge and Chester.

For Your Little Black Book

Morganics Family Farm

morganicsfamilyfarm.com

River Bend Farm

25 Branch Road, Far Hills • 908-234-1377

RBFAngus.com • GladstoneValley.com

Hillcrest Farm/Jersey Girl Cheese

2 Davis Road, Branchville • 973-703-5148

HillcrestFarmNJ.com

Rolling Hills Farm

133 Seabrook Road, Delaware Twp. • 609-731-9175

rollinghillsfarm.org

Chickadee Creek Farm

Titus Mill Road, Pennington

chickadeecreekfarm.com

Mishti Chocolates

206-569-5269

mishti-chocolates.com