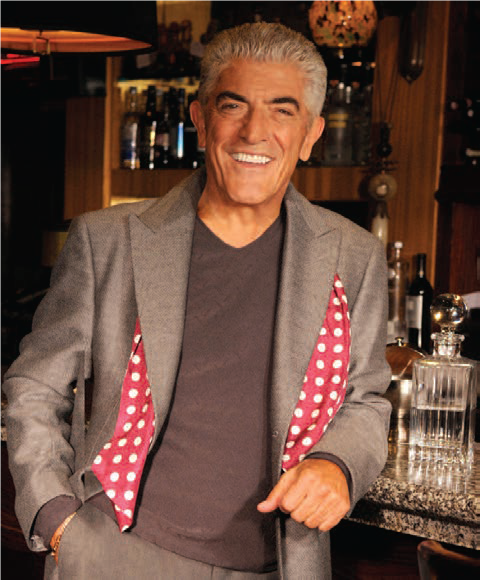

In the opening moments of Goodfellas, a murderous threesome played by Robert DeNiro, Joe Pesci and Ray Liotta struggles to dispose of made-man Billy Batts. It’s the beginning of the end for these characters, but for actor Frank Vincent, the part of Billy helped catapult him to iconic status. As “Shovel Ready” roles go, one might say this was the capo di tutti capi. EDGE Editor-at-Large Tracey Smith has made a study of the mob movie over the last year or so. Through her interviews, she has uncovered a rich tradition of storytelling, a dynamic passion for filmmaking, and a core of actors who care deeply about their craft. Frank fits this mold as well as anyone in the business. An accomplished performer long before he made his screen debut, he is always looking beyond the camera and over the horizon.

EDGE: You’ve delivered several indelible performances as a New York mobster, including Billy Batts in Goodfellas and Phil Leotardo in The Sopranos. But for the record, you’re a Jersey Guy.

FV: I couldn’t think of myself as anything else, even though I wasn’t born here. Of course, I know New York well. I’ve done a lot of New York movies and know all the boroughs. But I’m a Jersey guy. I’m proud to be from Jersey. I think it suits me.

EDGE: When did you move to the state? My father’s family came to America and settled in North Adams, Massachusetts. I was born in Massachusetts and so was one brother. My second brother was born in New Jersey. My father’s friend had a girlfriend in New Jersey, and he (my father) went out with them one time and met my mother, who was from Jersey City. They wound up getting married and eventually we moved back there.

EDGE: Who were your role models growing up?

FV: Like most men, my biggest influence was my father He was a very charismatic man—uneducated but very smart and hardworking. A great work ethic. He was the guiding light in my life. I loved my mother, but she was more of the disciplinarian in the family; my father was my idol. When I was a little boy I would watch him getting dressed in front of the mirror. He was a flashy guy, he loved to groom, his hair was always impeccable He wore Old Spice cologne and had a pencil-thin mustache. He saw himself as kind of an Errol Flynn type. My mother dressed nicely, too—when they dressed up, they dressed up. My brothers are the same way.

EDGE: Before acting there was a career for you in music. Was that your father’s influence?

FV: I think that actually started with my mother. I would come home from school for lunch and she always had music playing in the house. We would sit together and eat and listen to the radio. That implanted a love of music in my head. My father thought of himself as a singer, but he didn’t really have the ability—I think he was tone deaf. Yet he had the moxie to do it in front of people. Anyway, when I told my parents I liked music they made me take piano lessons, which I did not like because it took me away from the kids in the street. The Jersey City Department of Recreation had a drum and bugle corps, and I joined. I wound up being a bugler because I had taken some trumpet lessons. Many of my friends went on to become cops, fireman or went to jail, because it was a pretty rough neighborhood. But I stayed with the guys that played music. I finally ended up joining the St. Joseph’s Cadets from Newark. I traveled the country with them, and we were national champions. Competing in front of 70,000 people at Yankee Stadium as a 14-year-old gave me the confidence to go further. I was never afraid of an audience.

EDGE: How did you end up with your own band, playing the drums?

FV: I bought a set of drums for $100, auditioned for a band and got the job. Now all of a sudden I’m in show business! We were Bobby Blue and the Aristocats. We played in a lot of top clubs here and in the city. We were good. We were well-dressed. We were the real deal. One of the guys worked as an arranger for Frank Sinatra. Eventually I took over the band, and over the course of time we became a trio, Frank Vincent and the Aristocats. Between dates, I was in and out of New York sometimes four or five times a week working in recording sessions— backing up artists, working on albums, playing jingles. A record producer named Bill Ramal got me into that part of the business. He worked with Del Shannon, Dion and the Belmonts, Steve and Edie, and Paul Anka.

EDGE: What happened with the trio?

FV: Well, my piano player left me in 1969. That summer I hired a young guitar player who used to come to our club dates and occasionally sit in with us and sing. Our first gig was July 4th at the VIP Lounge in Seaside Heights. We ended up being the toast of the Jersey Shore that summer. We went from being piano, bass and drums to guitar, bass and drums.

EDGE: And that guitar player was…

FV: Joe Pesci. We had such chemistry. Not just playing. We’d do bits back and forth. I had a sort of Don Rickles thing going. The club entrance was right near the stage, so as people walked in off the street I’d always have something to say. We both got a lot of laughs and before you know it, we’re doing two hours of comedy a night. A couple of years later, this movie producer is in the audience and likes what we’re doing. He asked us both to audition for a low-budget movie called The Death Collector. Later they changed the name to Family Enforcer and put our faces on the cover. Joe played a little mob guy and I played a Jewish businessman. Bob DeNiro and Martin Scorcese saw that film and hired Joe to play Joey La Motta and me to play Salvy in Raging Bull. That was our first studio movie. I got my SAG card and an agent, and Joe got nominated for an Oscar. Thirty years later, 60 or 70 movies, TV shows, commercials—that was how it began.

EDGE: You mentioned Sinatra. Was he one of your main influences?

FV: Yes. The utmost person in my life, besides my father, professionally was Dean Martin. He wasn’t a great singer, but he was a great stylist. From him I learned timing, how to speak to audiences, how to carry myself, how to smoke a cigarette. Dean Martin was hypnotic. Frank would be second. Musically, I don’t think anyone in the world compares to him. I probably know the lyrics to every song he sang—that’s how much I listened to him. I learned to play the drums listening to his records. The style of music my band played was the music he sang.

EDGE: Do you think your father had an impact on your professional career?

FV: Sure. I learned to be fearless from him, that you cannot be afraid to fail. That’s what kept me going through my music years when I worked from week to week or month to month. When the acting came around, I wasn’t intimidated by Robert DeNiro or Bruce Willis or anybody that I worked with.

EDGE: What was your first meeting like with DeNiro?

FV: I had to audition for Raging Bull at a hotel on Central Park West. I went up the elevator and got to the door, knocked, and a production assistant let me in. I came face-to-face with DeNiro, and he said, “Hello Frank. I’m Bob and I loved your work in Death Collector.” I said, “Hello Bob, I loved your work in Deer Hunter.”

EDGE: How did you get along with Scorcese?

FV: He’s a first-generation Sicilian like myself, and I think that shared culture really opened a lot of doors for us. That’s probably why I did three movies with him. And, of course, Joe and I had that chemistry, which he utilized really well. Marty really knows what he’s doing when it comes to putting a cast together. His mother and father were wonderful people, in fact, may they rest in peace. It was like being home, this was the way my home was! At my house we always had Sunday dinners, I spoke a little Sicilian and Neopolitan, and we always had espresso and played cards afterwards.

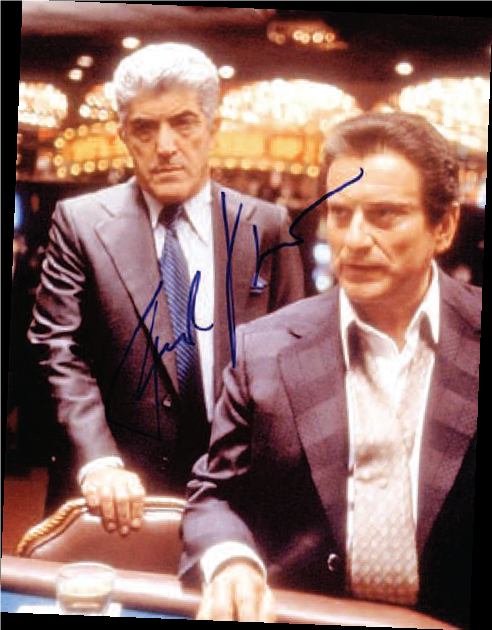

EDGE: About Pesci—he beat you up in Raging Bull and again in Goodfellas. Then you gave him a “well-deserved beating” in Casino. Did that even the score?

FV: You know [laughing] when you’re on a film, you don’t think “revenge” as you’re doing those scenes. It’s what the characters are doing, not you personally. It’s only afterwards, in interviews, that it comes up. But yes, it’s true, Billy Batts got his revenge. Although I think technically Billy got his revenge at the end of Goodfellas, when Joe got killed. And for the record, in those scenes those are stuntmen.

EDGE: All of the characters you’ve done have given you some interesting “street cred” in the Rap and Hip-Hop world.

FV: They have. In 1996, Hype Williams was directing the big-budget rap video for “Street Dreams” by Nas. It referenced the movie Casino and I was in the video. Hype asked me if I would serve as an acting coach for his first movie, Belly, which starred Nas and also DMX, Method Man and T-Boz. The rappers had already interviewed three traditional acting coaches and rejected them. They wanted a real “made guy” [laughing] so I went to meet with them and they agreed to work with me because of the image I portrayed. That’s the truth. And you know what? They had no knowledge of acting, but they were brilliant. They were all poets, so the dialogue came easy to them. It was keeping them on the spot so they stayed on camera that we had to work on. I also was in a couple of scenes. That movie was quite an experience.

EDGE: What roles do you look back on and feel like you really enjoyed doing?

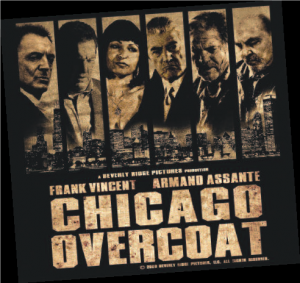

FV: I liked Lou Maranzano in Chicago Overcoat, which we shot in 2007 and was released in 2009. Lou had some interesting issues. Frank Marino in Casino was a good role for me, too, although it wasn’t a great speaking part. People think you have to speak a lot to have a big role but that’s not true. And of course, I enjoyed playing Phil Leotardo in The Sopranos because the writing was so brilliant. The level of discipline on that show was a real eye-opener as an actor. We shot each episode like a movie, on film, but in only 15 days. You could not deviate from the script. To change a single word—an uh or an and—you had to get permission.

FV: I liked Lou Maranzano in Chicago Overcoat, which we shot in 2007 and was released in 2009. Lou had some interesting issues. Frank Marino in Casino was a good role for me, too, although it wasn’t a great speaking part. People think you have to speak a lot to have a big role but that’s not true. And of course, I enjoyed playing Phil Leotardo in The Sopranos because the writing was so brilliant. The level of discipline on that show was a real eye-opener as an actor. We shot each episode like a movie, on film, but in only 15 days. You could not deviate from the script. To change a single word—an uh or an and—you had to get permission.

EDGE: Is Billy Batts the character you relate to most? It seems to be the one your fans gravitate towards.

FV: That’s certainly my most iconic role. You know, I didn’t realize how big Billy Batts would become—he really didn’t have a lot to do in that film. The fact I did that “Get your shine-box” scene with Joe is probably why it worked so well. If you played back all the takes we did at that bar, I mean, the timing of each was perfect every take. Marty said that to us. By the way, he also let Joe ad-lib in the famous “Do I make you laugh?” scene with Ray Liotta. Watch that scene again—you’ll see that Ray didn’t know what was coming.

EDGE: So will we see Billy again?

FV: In a way, you will. I have been working on a memoir with Steven Prigge, which I’m calling I Went Home and Got My Shine Box…Now What? Steven was my coauthor on the first book, A Guy’s Guy to Being A Man’s Man, which, by the way, is being optioned for a Hollywood comedy by J.C. Spink, who produced the Hangover films.

Editor’s Note: You may recall that Frank Vincent was our “cover boy” for the Gray Matter Issue earlier in 2012. You may also have seen him channeling the Rat Pack in a commercial for Ciroc Vodka with co-stars Sean (P. Diddy) Combs, Boardwalk Empire’s Michael Williams and Aaron Paul of Breaking Bad fame. Ever the entrepreneur, Frank is busy promoting Iso-Test, a performance-boosting dietary supplement. He is also prominently featured in Alan Robert’s new Killogy series of graphic novels, which debuted on Halloween. And if you are stumped for that perfect holiday gift, log onto frankvincent.com and check out the MOBblehead Doll, which utters Frank’s favorite movie lines, including Go home and get your shine box! Nobodys breakin’ up my party! and Give those Irish hoodlums a drink!