What happens when a game-changing product hits the market…and consumers just change the channel?

By Luke Sacher

Thomas Edison once said, “I can never pick something up without wanting to improve it.” The man who brought to millions the light bulb, phonograph and motion pictures embodied the spirit of invention and innovation as he churned out one culture-changing product after another. That same spirit is still alive and well today, driving an unprecedented wave of new, transformative consumer products and technologies.

It’s worth noting that Old Tom also laid more than a few bad eggs, some of which proved quite costly both to his investors and him personally. The electric pen, the spirit phone… who knows why they never caught on?

www.istockphoto.com

My point is that even when true geniuses are involved, and no matter how many hotshot business executives have green-lighted a product or how much money has been plowed into promoting it, there is no guarantee that people will buy what they are selling. And when they don’t, it’s a catastrophe.

I grew up in a family of Madison Avenue advertising executives. The ongoing conversation about marketing calamities—during meals, on car rides, and at the cocktail parties I was often allowed to stay up for—is a subject that still fascinates me. In my adult lifetime, I can think of more than a dozen “What were they thinking?” moments. Here are four you might remember, one you probably don’t, and one that predates me—which just might be the worst flop in history.

Photo by Tim Reckmann

GOOGLE GLASS • 2014

In the summer of 2010, the FOX animated series Futurama aired an episode entitled “The Eye Phone.” It was a blistering satire of iPhone-mania that featured a smartphone implanted directly into the eye socket, providing a “Head In, Heads Up” video display. “With the new Eye Phone,” the episode’s “Apple-esque” parody TV ad explained, “you can watch, listen, ignore your friends, stalk your ex, download porno on a crowded bus… even check your email while getting hit by a train. All with the new Eye Phone.” Meanwhile, back in the real world, a genuine Augmented Reality (AR) device was being designed and engineered by Google, in their cutting-edge X Development division: a pair of Luxottica designer eyeglass frames, fitted with a heads-up semi-transparent display equal to a 25-inch screen viewed from 8 feet away. Among its features was an HD video camera that recorded continuously for at least 10 minutes with no one knowing but the wearer. Google Glass was made available to consumers on May 15, 2014.

The initial reaction was euphoric. Time pronounced Google Glass (“Glass,” for short) as one of the best new products that year. Everyone who was anyone wanted one. It looked like something out of a 007 or Mission: Impossible flick. But there were issues. At $1,500, it was expensive. Other than the display and the spy camera, it offered nothing more than a smartwatch costing a third as much. And due to both potential health risks and battery requirements, Glass had no 4G LTE cellular capability. To use it for phone calls, it had to connect via Bluetooth to a smartphone somewhere on your person (Google Android recommended, of course).

Oh, also…it made you look like a rich dork pretending to be a creepy secret agent. Or just plain creepy.

Glass soon became the object of widespread public outrage over safety and privacy concerns. Laws were passed banning it from use while driving, as well as in banks, movie theaters, sports arenas, locker and dressing rooms, classrooms, casinos, bars, hospitals—you get the picture. Nine months after its release, in February 2015, Google suspended production.

Unwilling to relegate Glass to the ash heap of tech history, the company shifted gears and began focusing on another market. The product had enormous potential for people who needed real-time information while keeping both hands free, such as precision engineers and certain medical professionals. In July 2017, Google announced the release of its Glass Enterprise Edition and, this past May, Enterprise 2.

ninebot

SEGWAY • 2001

On December 3, 2001, after months of goosebump-raising build-up in the popular press, Dean Kamen— genius inventor of lifesaving medical devices and all-around good guy—unveiled his latest creation live on Good Morning America, in Manhattan’s Bryant Park. He called it the Segway. It was a phonetic spelling of segue, which (as we all know?) means “to follow without pause or interruption from one thing to another”. Kamen described his invention as the world’s first self-balancing human transporter. “This product is going to revolutionize transportation forever,” he promised. It will do for walking what the calculator did for pad and pencil. You’ll get there quicker, you’ll go farther…anywhere people walk.

By 2007, Segway—which carried a sticker price of $5,000—had reached only 1% of projected sales. Popular opinion deemed it nothing more than a status toy for bored celebrities, techies and people willing to risk severe injuries trying to learn how to ride it. This despite initial glowing reviews from the likes of Steve Jobs, who said the Segway might be “as big a deal as the PC.” Later, Jobs changed his mind, saying it “sucked.”

Not everyone gave up on the Segway. In 2010, British entrepreneur Jimi Heselden purchased the company, with plans to turn it around. Later that year, however, Heselden was unable to turn his own Segway around and drove it off a cliff to his death.

In the years that followed, Segway’s market dwindled down to mall cops and tourists. Kamen’s gyroscopically controlled, self-balancing single axle technology still had potential, however. In 2015, the Chinese company Ninebot purchased Segway and now markets a fleet of hoverboards and in-line scooters featuring this technology. Ninebot shipped more than a million scooters alone in 2019—more than 10 times the number of Segways sold in 17 years. In 2020, the company is debuting a dirt bike for adult motocrossers.

When asked about the Segway’s initial failure, Kamen references the Wright Brothers. “They certainly weren’t giving out frequent flyer miles by 1920,” he says. “But I don’t think anybody would say, ‘Hey Wilbur, hey Orville, how do you feel about that failure?’”

PERSIL POWER • 1994

All laundry detergents do two things, but we only think about one of them: They clean clothes. The other thing detergents do is damage clothes. Success in the suds biz depends on getting consumers excited about the first thing, and hoping they don’t notice the second thing. Striking the delicate balance between maximum cleaning and minimum damage dates back to 1907 when the Henkel Company created Persil, the first commercially available “self-activated” detergent. The product’s name came from two of its original ingredients: sodium perborate and silicate.

This product launch disaster happened across the pond, in Great Britain. In the early 1990s, independent tests showed that all major laundry brands available in the UK, including Persil, performed pretty much the same in removing stains. Around that time, Persil’s chief UK competitor, Ariel—made by arch-rival Procter & Gamble—introduced a “super compact” detergent featuring chemical catalysts to make it clean better using less soap per wash, and in colder water. Unilever/Henkel responded by developing a super-compact of their own, adding a manganese catalyst that they branded as the “Accelerator.”

Before new Persil Power hit the market, Procter & Gamble did something unprecedented in its history: It contacted its main competitor to issue a warning. P&G had tested the “Accelerator” and found it to be way too strong. It actually destroyed clothing after a few washes. The inevitable public outcry would damage the credibility of the entire detergent market. If Unilever/Henkel went ahead and released Persil Power as is, P&G promised to publicize its test results as extensively and graphically possible. The Persil folks responded by saying their test results looked just peachy, thank you, and in May 1994 rolled out the biggest advertising campaign in British detergent history—sinking a quarter-billion pounds into the product launch. P&G made good on its promise. One press release said: “If you use this product, your clothes will be shredded to the point of indecency.”

Within weeks, it was clear that Persil Power was a total train wreck. Despite an unprecedented advertising blitz, combined sales of Persil Power and regular Persil did not move the needle one bit. Far worse, thousands of new Persil Power users from Belfast to Brighton were reporting big problems. Their clothes were losing their colors after a couple of washes, and after a couple more, were disintegrating. A gentler formulation was rushed to market, but by then, it was too late. Consumer confidence was lost. A full product recall was issued, and Persil Power was discontinued. In 1995, Persil re-engineered its super compact formula to boost stain performance without a catalyst and released it as New Generation Persil.

How the two companies’ test results on Persil Power differed so dramatically—or why the Unilever/Henkel people completely ignored P&G’s warning—no one knows to this day. One theory is that Persil’s testing was done on brand-new garments, which would have been more resistant than older ones to the damaging effects of the new catalyst.

Today, Persil is manufactured and sold all over the world by both Henkel and Unilever. It came to the United States in 2015 and is sold exclusively at Walmart. Consumer Reports rated it the best detergent it ever tested.

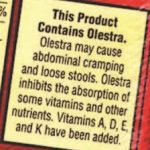

OLESTRA • 1996

OLESTRA • 1996

In 1837, English candlemaker William Procter and Irish soapmaker James Gamble— brothers-in-law through their marriage to two sisters—became business partners. In the ensuing decades, Procter & Gamble became synonymous with household brands including Ivory, Crest, Tide, Crisco, Jif, and hundreds of more products made with animal, vegetable, and petroleum-based oils and fats.

In 1968, P&G researchers synthesized Olestra, a vegetable oil (sucrose polyester) intended to be easily absorbed by premature infants. To their dismay, it worked in precisely the opposite way, passing straight through the digestive system with zero absorption. However, Olestra did have one intriguing property: It bonded with cholesterol and escorted it directly out the “back door,” so to speak. So P&G executives green-lit test studies to earn FDA approval for Olestra’s use both as a food additive and a drug. However, after six years, results showed that it did not reduce cholesterol levels by the FDA’s 15 percent requirement to qualify as “safe and effective.”

Unwilling to write off Olestra as a complete failure, P&G continued clinical trials for its approval as a calorie-free cooking oil substitute. It looked and tasted and behaved in the kitchen like Crisco, yet produced results closer to Castoria. Unfortunately, those trials also found that Olestra bonded with essential fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K (and carotenoids) the same way it did with cholesterol, flushing them out of the body, too. On top of that, one of the studies concluded that even moderate consumption of Olestra caused a statistically significant increase in diarrhea and gastrointestinal distress.

Fast-forward to 1987, by which time the company had amassed enough long-term data to submit an application to the FDA for Olestra. Nine years later, in 1996, the FDA approved its use in the manufacture of potato chips, tortilla chips, and crackers—under the condition that a health warning label is printed on every bag, reading “This Product Contains Olestra. Olestra may cause abdominal cramping and loose stools (anal leakage). Olestra inhibits the absorption of some vitamins and other nutrients. Vitamins A, D, E and K have been added.”

Fast-forward to 1987, by which time the company had amassed enough long-term data to submit an application to the FDA for Olestra. Nine years later, in 1996, the FDA approved its use in the manufacture of potato chips, tortilla chips, and crackers—under the condition that a health warning label is printed on every bag, reading “This Product Contains Olestra. Olestra may cause abdominal cramping and loose stools (anal leakage). Olestra inhibits the absorption of some vitamins and other nutrients. Vitamins A, D, E and K have been added.”

P&G approached Frito-Lay with a licensing deal to use Olestra to make fat-free potato and tortilla chips. Not long after, Lay’s, Ruffles and Doritos WOW! chips hit the store shelves, with millions of dollars in advertising and publicity behind them. A snack food that could be consumed by the bagful repercussion-free? Although that’s not exactly what the messaging was, that was the message received by America’s couch potatoes, and they were all-in.

The Internet hadn’t hit full stride yet and social media was still years away, but it didn’t take long for the proverbial you-know-what hit the fan. Soon everyone had heard an Olestra story, each seemingly worse than the one before it. The Center for Science in the Public Interest reported that a “63-year-old Indianapolis woman ruined three pairs of underwear and had no friends for two days after eating Olestra chips.” An independent study found that eating only 16 Olestra potato chips caused diarrhea in half of the participants. Meanwhile, people (as they still do now) were downing entire bags of these chips—far more than any testing had anticipated. Comedians were having a field day with “anal leakage” jokes. Damage control efforts proved futile and Olestra quietly disappeared from the market.

NEW COKE • 1985

NEW COKE • 1985

If you lived through the 1980s, you no doubt remember the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War. But how about the Cola Wars? During those fizzy-headed years of Miami Vice, Mad Max and mullets, Coke and Pepsi faced off in a grudge match for the title of King Cola.

First: a little history. For nearly a century since the birth of both companies, Pepsi had remained a comfortably distant competitor to Coca-Cola. During World War II, thanks to exclusive government contracts and exemptions from sugar rationing, Coke—not Pepsi—shipped out with America’s military, which resulted in the building of 64 bottling plants from Manchester to Manila and make Coke the most-recognized brand on the planet. In the postwar years, Pepsi was quick to target the only market left open to them, which to their great good luck happened to be the biggest ever: America’s Baby Boomers. In 1975, Pepsi discovered its competitor’s Achilles’ heel. It began airing commercials showing hidden-camera blind taste-tests (aka The Pepsi Challenge), which showed conclusively that people preferred the taste of Pepsi to Coke just over half the time. As a result, that year, Pepsi surpassed Coke in supermarket sales. Coca-Cola ran its own blind tests and, much to its corporate dismay, came up with identical results.

No one in Atlanta pulled the fire alarm until 1981 when new Coca-Cola CEO Roberto Goizueta and President Robert Keough set their chemists to work creating an entirely new “Holy Grail” formula that would beat both Pepsi’s and Coke’s original flavors. After three years of experimentation and blind-testing 200,000 consumers, they felt statistically certain that they had a winner. So certain were they, in fact, that they completely discontinued production of the original formula and replaced it with the new one, spending tens of millions in advertising and PR to ready the public for the switch. By the time they were ready to premiere “New Coke”, 96% of Americans knew about it—more than who could name the President of the United States (for the record, it was

Upper Case Editorial

Ronald Reagan). It was a masterwork of strategic marketing.

Except for one thing. It wasn’t The Real Thing.

People tried “New Coke” and freaked out. They hated it. They called it “Coksi” and “Pepsi in drag.” Five thousand nasty phone calls a day poured into Coca-Cola’s headquarters—and that was back when calling Georgia was a toll call. Songs were recorded and played over the airwaves: “Please don’t change the taste of Coke. Why would you want to fix it? It ain’t broke!” Sales cratered.

Goizueta and Keough had overlooked the most important and valuable quality of Coke: authenticity. To millions of Americans and billions all over the world, Coca-Cola was more than just a soft drink. It was an American icon. Changing its formula was akin to “updating” the Statue of Liberty with an 80s wardrobe makeover. Or adding a base in baseball. Or spitting on the Flag. Or Mom. Or her apple pie.

It took Coca-Cola exactly 11 weeks to bring back the original formula, renaming it “Classic.” Sales rebounded, then skyrocketed. Goizueta and Keough had survived one of the dumbest corporate decisions in the history of consumer products and taught every other marketer an important lesson. Now when you describe something as “New Coke” you need to say nothing more.

A common conspiracy theory remains that Coca-Cola deliberately launched New Coke as a pariah, in order to stoke loyalty for the true original. Well… at that time, my stepdad was president of the ad agency handling the Sprite and Minute Maid accounts for Coca-Cola, so he had a boardroom-side seat to the whole mess. When I asked him about it, he simply told me what Keough had said: “We’re not that smart, and we’re not that stupid.” Maybe the happy moral of this story is: Familiarity doesn’t always breed contempt.

BLAST from the PAST

In the mid-1950s, the Ford Motor Company launched an entirely new division to compete with rivals General Motors and Chrysler in the growing mid-priced field. Henry Ford II assigned the task to his “Whiz Kids,” a group of 10 veteran officers from the Army Air Force Office of Statistical Control who had steered Ford out of near-bankruptcy just after World War II. They were masters of corporate finance and management but had no practical experience with marketing cars. Using statistical analysis and the nascent social science of “motivational research,” the Whiz Kids set about producing a car that offered everything that the average customer could possibly want—and wound up creating one that nobody wanted: the automotive dumpster fire we now know as The Edsel.

The Edsel was available in four trim classes, six body types, and 90 head-spinning color combinations. It offered several design wow-factors, such as “Teletouch” automatic transmission, which was operated by push buttons located in the center of the steering wheel. This happened to be where the horn button was in virtually every car made since 1920. One can only imagine how many times Edsel drivers were “wowed” by both frightening silence and physical agony after pressing their palms full force into the jagged edges of the Teletouch control center at the moment of a traffic emergency. You get the idea.