Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Drywall*

*BUT WERE AFRAID TO ASK

By Jim Sawyer

www.istockphoto.com

Drywall giveth and drywall taketh away. If you’ve ever had to build a new structure, add to one, or repair one that’s old or damaged, you probably understand the myriad advantages of using drywall. Relative to traditional construction and plastering techniques, drywall is inexpensive, light, safe, and requires far less expertise to install. And when it comes time to knocking something down, drywall is just as quick, easy, and inexpensive.

The disadvantages of drywall? It is easily damaged, it can be tricky to repair, it doesn’t do much to baffle sound or to insulate and, if it gets wet, well, there’s that nasty mold issue. In areas of the country (including our own) where floodwaters have inundated homes constructed with drywall, the result is almost always a gut job. Left to mold, a drywall home can quickly turn into a lung-choking teardown. By contrast, older historic homes featuring traditional plaster just need a basic hose-down after a flood; a splash of paint and they are good to go. No mold. No problem.

So it’s a trade-off. But on the construction industry’s big balance sheet—where the speed of construction and demolition can make the difference between a big profit and a razor-thin one—drywall is a no-brainer.

That certainly accounts for the tens of billions of square feet manufactured in North America each year. Say what you will about the ups and downs of the housing market in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, but the population of this continent continues to boom and people need places to live. So until some better material comes along, drywall is here to stay.

WHAT IS IT?

WHAT IS IT?

Drywall goes by many names: wallboard, plasterboard, and sheetrock among them. Whatever you call it, there isn’t a whole lot of science to drywall. It typically comes in a 4’ x 8’ sheet, usually 3/8” or 1/2” thick, encased in paper or a paper-pulp material. Thinner sheets are sometimes used to negotiate curved surfaces. Drywall is attached with special screws to wood or metal studs, and sometimes glued as well (especially on ceilings).

The white-gray material sandwiched between the paper is gypsum. Among its many qualities, gypsum is inherently fire-resistant. In addition, some drywall products come impregnated with glass fibers in order to further slow the spread of flames and smoke. Local building codes usually require that this type of board—which is 5/8” thick—be used in furnace rooms and garages, or homes heated by wood stoves.

Structures prone to flooding (either by Mother Nature or from plumbing or roofing mishaps) or in high-humidity areas are often built with mold-resistant or moisture-resistant drywall. Note the use of the word “resistant.” It does not imply mold- or moisture- “proof.” Mold-resistant boards are treated with a special coating and generally do not have paper, which is a favorite home of fungus. Contractors typically use mold-resistant drywall in bathrooms and kitchens. Sometimes this material is called “greenboard,” which technically is incorrect. Greenboard is slightly different (although it can be used in the same situations); it performs best in high-humidity areas of a home, such as a laundry room or damp basement.

What should you do if drywall is no longer dry? Tear it out and replace it. What if you detect mold? Do not dither, especially if someone in your home or workplace is allergic to the spores. The drywall should be replaced and the mold remediated. There are obviously professionals who do this, but an Internet search can show you ways to do it yourself. Proceed with care and caution. As with many dangerous organisms, the mold you see isn’t always the stuff you need to be most concerned about. If moisture has entered the back of a sheet that has been primed and painted, it has already had a lot of time to grow and spread before you start breaking it up. In these situations, trust your nose over your eyes—you’ll be able to smell the mold before you see it. And keep in mind that tearing it out is likely to release spores back into the environment and possibly into places it hadn’t been before, such as your HVAC system.

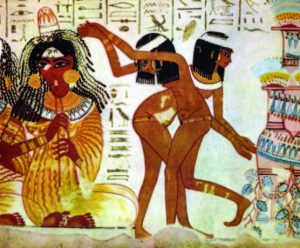

The British Museum

WHO INVENTED IT?

Now that the basics are out of the way, how about a little history? The use of gypsum as a wall material dates back more than 3,000 years. It is easy to get out of the ground, simple to process, and holds colors really well.

It was quarried for plaster in ancient Egypt in the Old and New Kingdoms—in 2017, archaeologists identified one quarry on the east bank of the Nile that measured three square kilometers. The ancient Egyptians discovered that gypsum could be ground into a fine powder and mixed with water to produce a bright, durable skim coat of plaster that could hold paint extremely well on interior walls in homes, temples, and tombs. Thousands of years later, it still looks great. The mineral owes its name to the ancient Greeks, who used it in much the same way. Gypsos actually means “plaster” in Greek.

www.istockphoto.com

Gypsum or lime were used more or less interchangeably as a component in plaster in the ensuing centuries. One of the most famous sources of plaster was in the Montmartre section of Paris, hence the name Plaster of Paris. The French like to say there is more Montratre in Paris than Paris in Montmartre.

They’re speaking literally in this case—the gypsum and lime deposits there were used in plaster and paint in the city for centuries. In the hands of French artisans, it was made to look like wood, metal, and stonework when those materials were either too cumbersome or expensive, or just unavailable.

US Gypsum

The process by which gypsum becomes plaster has remained relatively unchanged. It is heated to about 300 degrees, until the moisture is released and it becomes a dry powder—which is then reconstituted with water to be applied or shaped as needed. Gypsum being a mineral, it has other uses, too. For example, it was used in colonial America to improve soil quality; Ben Franklin was a huge proponent of this particular use, which reduced runoff and delivered additional nutrition to plants. In the early days of Hollywood, shaved gypsum was sometimes trucked in to mimic snow. Although gypsum is used in the manufacture of Portland cement—making up two or three percent of the mix—it is not what makes sidewalks sparkle (that’s mica). In case you’re wondering, Portland cement gets its name from the Isle of Portland, on the southern coast of England, not from Portland ME or Portland OR.

Getting back to drywall, the world’s first “wallboard” factory actually opened in England, in 1888, in the English town of Rochester, about 30 miles east of London on the River Medway. The Industrial Revolution was shifting into high gear and an alternative to traditional lath-and-plaster construction for interior walls intrigued British homebuilders: Wallboard used far less wood and required limited plastering expertise, and also avoided the weeklong drying process of traditional plastering. In addition, it could be put up in a poorly heated environment, which was a Godsend in England with its cool, damp climate (and historic issues with central heating). By the 1920s, it was the material of choice in most new construction in the UK.

In America, the plasterboard revolution came a bit later, and shifted into high gear during the post-WWII building surge. The first drywall factory in the U.S. dates back to around 1900, in upstate New York. According to the web site gypsum.org, the product was initially favored because of its fire-resistant properties and featured multiple layers of gypsum (which was cheaper and more plentiful than lime plaster) sandwiched between two pieces of wool-felt paper. In 1917, US Gypsum Corp. debuted “Sheetrock,” the now-familiar single, non-layered sheet of gypsum plaster completely encased in paper, which could be joined with smooth, even seams. At the 1933 Century of Progress World’s Fair in Chicago, several building were constructed almost entirely of Sheetrock, which was a huge marketing coup.

By the Baby Boom years, when more than 20 million new homes were constructed in America, drywall was the cheap and easy workaround for traditional plastering. It has continued on as the material of choice for new homes, renovations, home repair projects—you name it.

FEMA

WHAT IS “CHINESE” DRYWALL?

In the seven decades that drywall has been widely available to homebuilders and homeowners, the domestic supply has had no problem keeping up with the demand, as gypsum is plentiful and easy to process in North America—until the early 2000s, that is. You probably remember the housing boom, but do you also recall that no fewer than nine major hurricanes smashed into Florida in the span of two-plus years, and then Katrina inundated New Orleans in 2005? Demand for drywall soared and caught North American manufacturers by surprise. With the supply low and prices high, many builders in the Southeast turned to a new source: China.

Unfortunately, drywall factories on the other side of the Pacific were focused on production and profitability rather than safety, and as a result, countless millions of square feet of defective or contaminated product found its way into American homes. The first sign that something was wrong came in the form of complaints by homeowners that exposed copper surfaces were turning black and “ashy.” Also, new refrigerators and air conditioners (which contain copper coils) were malfunctioning.

New West Gypsum Recycling

This made people wonder what was happening to their copper pipes and wiring—and they were right to wonder. The cheap drywall was giving off volatile gases, including hydrogen sulfide, which corrodes copper and also created health issues that included a range of upper respiratory problems. By the time the problem was identified, the tainted drywall had been used in somewhere between 50,000 and 150,000 homes; no one can say for sure because much of the product bore no markings that could be traced back to a specific manufacturer. One manufacturer that did pop up fairly often was Knauf, a Tianjin-based company with a deceptively European-sounding name. Some estimates put the amount of Knauf drywall unloaded in New Orleans and various Florida ports at close to a billion pounds between 2003 and 2009. In the aftermath of this debacle, a New Orleans court ruled that homeowner’s policies had to cover the remediation of contaminated drywall. The IRS also provided tax relief for people who suffered property damage because of the tainted product.

www.istockphoto.com

They Did What?

While the substandard Chinese drywall flooded the market in the mid-2000s, domestic drywall producers—who had been ramping up production since the late-1980s—doubled down and invested heavily to further increase their output. Consequently, the deflation of the housing bubble in 2008–09 devastated the industry. North American drywall companies were suddenly stuck with huge supplies and withering demand. Many were in no shape to wait for the economy to rebound.

All was not lost, however. As the housing market receded, a growing number of builders, flippers, and rehabbers began snapping up cheap properties and foreclosures and demand for drywall began to creep up again. However, contractors noticed a rise in cost on drywall at a time when it should have been bargain-priced. This was accompanied by an inexplicable reluctance on the part of manufacturers to compete on price. Obviously, since the manufacturers could not boost profits by increasing volume, they had to raise their prices.

There is nothing illegal about this…unless they plan to do it together. Which, apparently, they did. The result was a class-action suit against eight companies near the end of 2012 that ended with a nine-figure settlement. It wasn’t the first time drywall companies had been slam-dunked by the courts; price-fixing litigation dates back to the 1920s in North America.

WHERE ARE WE NOW… AND IN THE FUTURE?

We are in good shape. Today, the drywall supply is safe and sound—which is good to know in an era of increasing environmental sensitivity. Unused sheetrock scraps can actually be recycled, keeping thousands of tons out of landfills each year. Also, a steady demand for installation provides jobs for millions of people who do not have traditional construction skills, creating an entry point into an important trade. The retail price in New Jersey for drywall is $10 to $20 for a 4’ x 8” sheet (depending on type and quality) and another $50 or so per sheet to install professionally, including labor, supplies, and equipment.

Since you’ve made it this far, you are probably wondering, “What’s in the future for drywall?”

I’m so glad you asked.

The industry is aware that its product is somewhat problematic in the climate-change picture, in that it does not insulate particularly well. A new material called ThermalCORE, developed by the German chemical company BASF and National Gypsum, a U.S. company formed in the 1920s, could be a game-changer for builders and consumers. The new drywall material is impregnated with tiny wax beads encased in plastic shells. During the day, the wax melts and absorbs heat. At night, the wax hardens, releasing the stored heat.

Builders in Europe have been testing a version of this technology and it has demonstrated an ability to reduce energy bills by as much as 20 percent. The cost of using ThermalCORE in a typical home in New Jersey would probably raise its construction cost by $5,000, which would be recouped in about five years.