Christian McBride may be the hardest-working man in Jazz. The virtuoso bassist has played on nearly 300 records and has earned three Grammys for his own albums, which number more than a dozen heading into 2014. McBride learned his craft from his father (Lee Smith) and great uncle (Howard Cooper), refined it further at Juilliard, and went on to play with a who’s who of jazz luminaries, including Chick Correa, Sting, Pat Metheny, Diana Krall, David Sanborn, Joe Lovano, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, Milt Jackson, Benny Green and Ray Brown. All by age 40! McBride and his wife, jazz singer Melissa Walker, live in Montclair, where they lead the Jazz House Kids program and play starring roles at the annual Montclair Jazz Festival. Next March, he will host Jazz Meets Sports at NJPAC, an evening of music and conversation with sports superstars and jazz connoisseurs Bernie Williams and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Editor at Large Tracey Smith, who knows a thing or two about jazz herself, talked to McBride about the next step in his already over-the-top career.

EDGE: You’ve made a really impressive transition from in-demand sideman to bandleader. How does that journey work?

CM: As a sideman, when someone hires me for a gig, my first job is to serve the vision of that bandleader. It’s almost like being an actor—if someone calls you in for a role in a movie, you have to thrive within that role. Musicians often say they don’t want to have any limitations or work where there are guidelines. Finding your own place within these guidelines? For me that’s fun! It means I can do this but I can’t do that—or vice versa. Hmmm, let me see what I can find in here. I think that’s how I’m able to still retain my own identity while serving the bandleader.

EDGE: Talk about your work with Chick Correa and Sting.

CM: I’ve had a working relationship with Chick Correa since 1996. And every group I’ve played with him in, it’s quite surreal—he allows me to do whatever I want, do whatever I hear. He wants me to read the music he gives me, but once I get off the paper, I can do my thing! He’s really cool. He trusts me. I’m appreciative and honored by that. Sting, on the other hand, now this is how I think most bandleaders are…or at least should be. When I first started working with Sting, he was only just a little familiar with my playing. He’d heard a couple of the songs I had played on, but mostly it came from reputation. A few of the guys in the band told him if he was looking for a new bass player, then he should look at Christian McBride. When I started rehearsing with him, I realized I had to earn his trust, because we hadn’t played together before. To gain a bandleader’s trust, you must do exactly what they ask you to do—don’t step out of bounds, gain their confidence, and then when they start trusting you more and more, with each performance you get to establish more of your own identity, while serving the bandleader’s vision.

EDGE: Isn’t that still constrictive?

CM: Why would I go on Sting’s gig and start playing all my Ray Brown licks? That isn’t what’s called for. It’s about being selfless and serving the vision. After a few months of playing in his band I was able to throw in—every once in a blue moon—some of my own stuff. Sting would look over and give me a wink, or he would look over and give me a frown (laughs) depending on what lick it was.

EDGE: Now you are primarily a bandleader. Did that take some settling in?

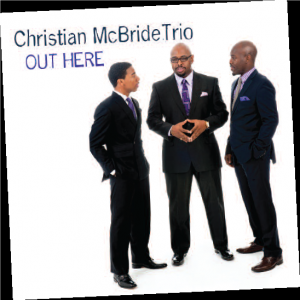

Photo courtesy of Christian McBride

CM: Yes. It’s taken quite some time to feel comfortable being a bandleader all of the time. Over the last, I would say, five or six years, the majority of my time has been dedicated to all of my own projects, my band—Inside Straight—my trio, my big band. Before that, I kind of just dibbled and dabbled at it; most of my time was spent playing with other people, being the sideman. It wasn’t a very good balance of being able to do both. I think most people viewed my being a bandleader as something I did every once in a while, when I wasn’t busy with Pat Metheny or Chick Correa. But now the tide is starting to turn.

EDGE: Both roles demand a certain degree of, as you mentioned, selflessness.

CM: I think that would be the main thread. As a sideman, you have to realize that you are there to serve the vision of the bandleader. Too many musicians are always looking for someone to tell them how great they are, even when it’s not their gig. They somehow want to have a lot of “say so” even though they’re not the bandleader. But that’s not what it is…the greatest musicians I’ve ever been around are very selfless musicians, and as a bandleader you have to be sensitive to your sidemen or collaborators. It’s a democratic process. In order for them to help you carry out your vision, they have to be on your side. You can’t be selfish, you can’t be a mean-spirited slave-driver. That only works for a hot minute, it doesn’t work for the long run (laughs). The band will turn on you at some point.

EDGE: Who do you consider your important influences?

CM: My primary influence when it comes to composition has always been Wayne Shorter. I cannot write like him. Nobody can write like him. In terms of what he writes, and how he writes, he’s always been my number-one hero. But then, there are musicians like Duke Ellington, Oliver Nelson, Chick Correa—they have always been some of my biggest inspirations.

EDGE: When I listen to you, I hear Ray Brown with Jaco Pastorius bass lines. Who are your musical mentors?

CM: Well, those two people you just named are my top two influences of all-time. If I could somehow tell someone what my playing is based on, it would be those two guys, Ray Brown and Jaco Pastorius. Again, particularly with the electric bass, I’m not as well-balanced playing both the acoustic and electric bass, at least publically, as I once did with my old band, The Christian M Band. I would say by the end of next year or early 2015, I want to start doing some work with my fourth group, called A Christian McBride Situation, which is a pretty even balance of acoustic and electric instruments. Ray Brown, Jaco, Ron Carter, Bootsy Collins, they are all my top heroes.

EDGE: 2013 has been a busy year for you.

CM: It has. I’ve had two CD releases already—People Music, with my group Inside Straight was released in May, and my new trio’s CD, called Out Here, was released in August. I also performed at the  University of Maryland a piece I was commissioned to write for the Portland Art Society, The Movement Revisited. It’s a four-part suite dedicated to four major figures of the Civil Rights Movement: Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., performed by my Big Band and Washington DC’s Heritage Signature Chorale, with spoken word selections by special guests, including civil rights activist and artist Harry Belafonte.

University of Maryland a piece I was commissioned to write for the Portland Art Society, The Movement Revisited. It’s a four-part suite dedicated to four major figures of the Civil Rights Movement: Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., performed by my Big Band and Washington DC’s Heritage Signature Chorale, with spoken word selections by special guests, including civil rights activist and artist Harry Belafonte.

EDGE: The digital age has certainly changed the recording industry landscape. How has the Internet changed things for you?

CM: It’s been like the Wild Wild West. It’s definitely a new frontier for everyone in the music industry. I think we’re still trying to plant our feet to try to get some stability. It seems like it is affecting everyone across the board, not just jazz musicians. One could argue that it is leveling the playing field, but I think that is only half-true, because what is happening now is that people are crafty and they are finding ways to get around paying for music. That’s not good on any level, because artists have to make a living. I don’t know how we can somehow change the thinking of Americans. I really feel it’s only an American problem, because people have no problem paying for music anywhere else in the world—even people who don’t have a lot of means. They realize the importance of art, but it seems like here it’s, “Why should we pay for music? All these guys are millionaires anyway!” Someone always has this knee-jerk reaction that all musicians are millionaires, or we don’t need the money, or what we do is not really an occupation, it’s a hobby.

EDGE: Who’s on your playlist when you are listening for pleasure?

CM: I really don’t do as much recreational listening anymore. I’m working on so many different projects, that most of my listening is dedicated to that. But James Brown usually dominates any of my musical devices. And there is always plenty of Cannonball Adderley, Ray Brown with Oscar Peterson, plenty of Quincy Jones—especially during his big band stuff. Those are always going to be in my player.