Buzzing Under the Radar

In this year of vaccine hyper-awareness, the first-ever vaccine against the deadliest of all human parasites has gone almost unnoticed.

By Mark Stewart

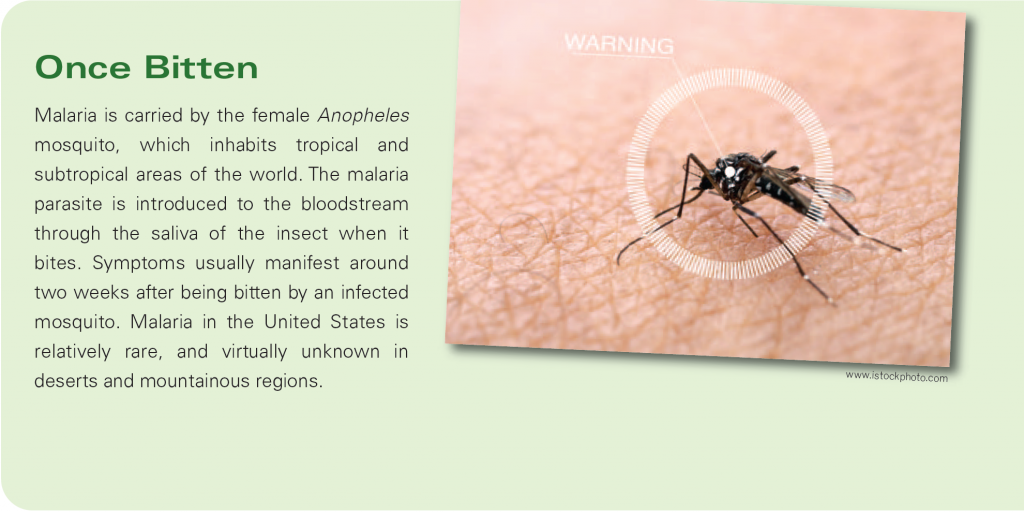

Over the past year, chances are that you have heard more facts and figures about vaccines than in all of the other years of your lifetime combined. Yet while we have all become intimately familiar with the COVID-19 vaccine, there is another vaccine on the market, which—in any other year—would have been the real headline-maker. Last year, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that it had approved use of the first-ever vaccine that is effective against malaria, a mosquito-borne disease that can kill within 24 hours of its flu-like symptoms appearing.

Over the past year, chances are that you have heard more facts and figures about vaccines than in all of the other years of your lifetime combined. Yet while we have all become intimately familiar with the COVID-19 vaccine, there is another vaccine on the market, which—in any other year—would have been the real headline-maker. Last year, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that it had approved use of the first-ever vaccine that is effective against malaria, a mosquito-borne disease that can kill within 24 hours of its flu-like symptoms appearing.

“Malaria vaccines have been in development since the 1960s,” says Dr. William E. Farrer, Chief of Infectious Diseases at Trinitas (left). “On October 6, WHO released a recommendation for widespread use of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine among children living in sub-Saharan Africa and other regions with moderate to high P. falciparum malaria transmission.”

Plasmodium falciparum is the parasite that transmits falciparum malaria, the deadliest form of the disease, which accounts for roughly 50% of cases worldwide and virtually all malarial deaths. For the record, that makes P. falciparum the deadliest of all human parasites. “The vaccine requires three primary shots and a booster,” Dr. Farrer explains. “In large trials, it decreased clinical and severe malaria by about 30%. This is only moderate efficacy, but represents a historic step forward in controlling malaria and could prevent many cases of this dread disease and many deaths.”

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director General, also described it as a historic moment, predicting it would prevent thousands of deaths a year. Currently, malaria is estimated to kill more than a quarter-million young people annually and over 400,000 in all (estimates fluctuate wildly depending on the source, but the numbers are undeniably huge). Even when it does not kill, malaria can return to sicken the same person several times over the course of a lifetime, or even in the same year—devastating the immune system over time, which makes it vulnerable to other diseases.

The new vaccine, which has been recommended for children five years old and younger, marks a significant step in an effort to conquer malaria that has seen worldwide deaths drop by 60% in the last two decades, and the number of cases cut nearly in half. Unfortunately, progress reached a kind of plateau around 2015 and the numbers have remained more or less constant since then. The recent breakthrough, which activates the immune system to battle the malaria pathogen, owes much to the work done in speeding COVID vaccines to market.

The new vaccine, which has been recommended for children five years old and younger, marks a significant step in an effort to conquer malaria that has seen worldwide deaths drop by 60% in the last two decades, and the number of cases cut nearly in half. Unfortunately, progress reached a kind of plateau around 2015 and the numbers have remained more or less constant since then. The recent breakthrough, which activates the immune system to battle the malaria pathogen, owes much to the work done in speeding COVID vaccines to market.

That being said, malaria is not caused by a virus, like COVID, nor by bacteria. Malaria is spread through a parasite which has over 5,000 genes, as opposed to SARS-CoV-2, which has only 11. That is a major reason why malaria has been so good at befuddling vaccine researchers. Indeed, the new RTS,S vaccine will still need to be combined with conventional malaria-prevention strategies—insecticides, netting and artemisinin-based drug therapies—in order to be fully effective. Artemisinin, discovered in 1972, is extracted from sweet wormwood, a plant used in traditional Chinese medicine; it earned the woman who discovered the breakthrough medicine, Tu Youyou, a Nobel Prize. The maddening aspect of fighting malaria is that a vaccine series must target the parasite at all of the different stages of its life cycle. The idea is to “get it” at one stage if it “misses it” at another, with the goal being to kill the parasite before it infects the liver.

Impact on the Home Front

Impact on the Home Front

Does the malaria vaccine have any relevance here in New Jersey? Absolutely. More than 2,000 malaria cases are reported in the United States each year, the vast majority coming from Americans vacationing in tropical countries or returning to their countries of origin to visit friends and family. Malaria can be transmitted to a fetus by its mother when bitten by a mosquito carrying the disease, resulting in low birth weight or premature delivery, as well as other more serious (and potentially deadly) health problems to a newborn.

The number of reported cases in Western Hemisphere nations with strong ties to the Garden State—including Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua and Haiti—top 5 million annually. That pales in comparison to India, which recently topped 100 million cases. Vietnam and Indonesia may have more than an estimated half-billion cases in a typical year.

Humans and mosquitoes both thrive near water, and thus have lived together for countless thousands of years—so long, in fact, that this relationship has “imprinted” itself on our genome. The origin of sickle cell anemia, for instance, is a genetic variation that very likely began as a result of malaria. Most people develop antibodies against malaria by the time they reach adulthood, but it takes a grim toll on children, particularly in Africa, where more than 90% of the world’s cases are recorded. The new vaccine completed its first trial run from 2019 to 2021 in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. It proved particularly effective against Plasmodium falciparum—as mentioned earlier, the deadliest malaria parasite (there are five in all).

www.istockphoto.com

Perhaps because humans and mosquitoes share an evolutionary history, the disease has shown an ability to mutate in response to everything we’ve done to fight it. It is anticipating the next mutation (and the next and the next and the next) that also proved challenging to the development of an effective vaccine. An example of this is the discovery in 2019 of a malarial strain that is resistant to Artemisinin. The mutation took place in Africa instead of Southeast Asia (where malaria mutations typically take place), further raising concerns because the parasite would have mutated independently to resist treatment.

A First Step, But Hardly the Last

The new RTS,S vaccine is not the be-all end-all in the fight against malaria, as Dr. Farrer pointed out. The 30% effectiveness number has drawn criticism from those who would wait for a more effective vaccine before launching the ambitious four-dose campaign in some of the world’s most remote, at-risk regions. However, it is an enormously encouraging first step upon which better vaccines can be built. The mRNA technology wielded against COVID, for instance, holds huge promise in this regard.

www.istockphoto.com

The new vaccine, which goes by the brand name Mosquirix, is the culmination of a research and development partnership, spearheaded by the pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, that began in 1987. In recent years, it has been funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, among others. In addition to being the first malaria vaccine, Mosquirix holds the distinction of being the first-ever vaccine for any parasitic disease.