Read this story before you buy that painting!

Art is a very personal thing. You must like it when you buy it, because you may have to live with it. The chances of an average Joe (or Jane) finding something exceptional out of pure, dumb luck are probably less than 5 percent, meaning you’d have to gamble on 25 or 30 paintings before finding a monster bargain. Who’s got that kind of time? Or money? Or wall space?

www.istockphoto.com

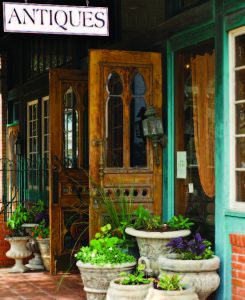

If you are someone who has decided to invest a few thousand dollars (or much more) in high-quality art, and are determined to go it alone, the places you are most likely to encounter the painting that sings to you are an antique store, auction, estate sale or a gallery that specializes in older works or works of listed artists. Often, like true love, you find that special work of art when you aren’t even looking for it. An unseasoned buyer may panic and pass…or panic and overpay.

Things can get especially complicated if there is no signature and no attribution. How in the world do you get a value? How do you know the price a gallery or dealer or antique store slaps on a mystery painting is fair? Unfortunately, the answer is, “It’s a muscle you work over time.” Experience, research, some wins, some losses. Usually, the first thing I’ll ask myself in these situations is, “Does this painting accomplish what it’s supposed to accomplish?” That being said, my husband and I have both bought paintings that passed the basic sniff test, but ultimately weren’t what we wanted them to be.

If I form an emotional attachment to a painting, often that’s enough to spend $500 or $700. I have works of art that I adore with no signature and I couldn’t care less. They serve me well. And sometimes that’s okay. Again, buy what you like. That’s a decent starting point.

So what’s my magic formula for buying smart? As I look back on my career and experiences as an art historian, dealer, appraiser and collector, I think it’s a little bit of patience, a fair amount of scholarship, and being in the right place at the right time. I offer as evidence four war stories…

So what’s my magic formula for buying smart? As I look back on my career and experiences as an art historian, dealer, appraiser and collector, I think it’s a little bit of patience, a fair amount of scholarship, and being in the right place at the right time. I offer as evidence four war stories…

YOUTH IS SERVED

When I was starting the field in the early 1980s, the gallery owner I worked for purchased an unsigned American impressionist painting for around $1,000. I felt it had been executed by John Leslie Breck (1859–1899), the artist who is often considered the first American to bring the French Impressionist art movement to the U.S., after befriending Monet. Breck died at 39, so his body of work was very small. I implored him not to sell it; I told him I had this hunch. This took me on another adventure. I knew someone in Boston at the St. Botolph Club, an exclusive arts club which, at the time, was still restricted to male membership. He arranged a private viewing of several Breck paintings and drawings they had in their amazing collection. I left completely convinced that the $1,000 painting was by him, which made it a $30,000 painting. Today, it might sell for over $300,000. I was just 22 years old at the time.

ART BUYER’S CHECKLIST

ART BUYER’S CHECKLIST

The more you know, the less money you’re likely to blow so, as mentioned earlier, a little bit of scholarship can go a long way. However, anyone who comes across an old painting that “speaks to them” should be armed with a checklist to help keep a potential investment in perspective:

- Does it appeal to me?

- Is it likely to hold the same appeal to others?

- Does the subject matter make sense?

The old saying that a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing applies here. You may know that an artist’s work is prized, and make an educated guess on value. But have you considered what the subject of your painting is? If an artist is known for seascapes and you find a painting of his or her grandmother, you are not comparing apples to apples. You are comparing apples to oranges (or worse).

- Is the condition acceptable?

Here you have a little wiggle room. If a painting is centuries old and has damage or evidence of in-painting, you can live with that. If a painting is 50 years old and in poor condition, as an investment you really can’t tolerate that. Remember to check front and back.

- Has it been repaired?

Never ever compare a painting that’s been restored to one that is in pristine condition. The most obvious signs of repair is if a painting has been re-lined or if there is an application of another material. So for instance, reinforcement behind an oil on canvas means the integrity of the painting has been disrupted. There was a tear, or mold or water damage. Also, don’t spend serious money on a painting older than 1960 or so without first seeing it under a black light (a handheld one is a modest investment). New paint fluoresces. However, be aware that masking varnishes can be used—if it’s worth faking, it will be done.

- What info is on the back of the painting?

Are there numbers in the corner, drawn or written in chalk?This suggests that has been up for auction at some point and you may be able to find out more about it—including the selling price. Is there a label that says it was exhibited at a gallery or museum? Or is there some record of ownership? All of these details can be very helpful in your sleuthing; your goal is to extract the painting’s provenance, which can dramatically affect its value.

- Is it in a quality frame?

A period frame signed by the artist (usually just initials) indicates that he or she went to great expense to showcase the work.

- What does the seller know about the painting?

Never buy a painting without asking the seller what he or she knows about it. It is not out of bounds to ask where the seller bought it, either. Provenance can be critical in determining the fact behind a work of art, not to mention its value.

- Have you done any research?

A lot of people are discouraged researching art because auction sites generally don’t reveal selling prices unless you subscribe to a service, like Artfact or Artnext, that gives you access to this information. And auction sites are often among the first entries to come up in Google searches. The good news is there are some great free research sites, including ones run by the Getty Research Institute, the Smithsonian (Siris), the National Portrait Gallery, the Guggenheim, the Louvre and the National Gallery of Art.

- Is my information current?

Don’t assume that something that was worth “X” 20 years ago will be worth “2X” today. In the late 1990s, people were killing each other to buy Louis Icart. Now I can’t give them away.

www.istockphoto.com

FAIRY TALE ENDING

Once upon a time, we bought five small illustrations of nursery rhymes at a local auction. They were from the late 19th century and were exquisitely done. They bore no signatures. For the better part of 10 years, I tried to get attributions. I didn’t even know if they were American or British. I did feel strongly that they were done by a female artist. There were fingerprints—not literally, of course, but tantalizing clues. I did extensive research and contacted many colleagues in the art world, but could never get an exact match to an artist. We have a particular client who really likes unpublished illustrations. I pulled them out for him because I thought he might recognize the work. He loved seeing them, yet even he couldn’t shed any more light on their origin.

Some time later, we were up in Massachusetts visiting an art dealer friend. She happened to own a book from the same period that had never been published. She asked if I’d like to see it, and the instant I saw just the title page I knew exactly who my artist was. It was someone with whom I was well acquainted…I could have kicked myself! The artist was Laura Coombs Hills (1859–1952) and it turned out my illustrations were meant to be Christmas cards published by Louis Prang & Co. circa 1897. And with this new information, the value of the five pieces went up about eight times.

www.istockphoto.com

BUT I BOUGHT IT IN AN ANTIQUE STORE

Overpaying for art in antique stores happens from time to time. That doesn’t surprise me. There is not as much crossover in the fields of furniture and art as there should be, so some dealers don’t know a whole lot more about a painting than what they paid, and maybe what someone paid for something similar at an auction. That can lead to overpricing. However, it also means you can stumble past a phenomenal bargain without even realizing it. You may also have more negotiating room than with a dealer of fine art. Antique stores often try to buy items with a 100% markup in mind. This is because they deal with decorators, who take a big bite out of the pieces they purchase on behalf of their clients. It’s built into the business, so why not haggle a little?

STEALING ONE FOR A C-NOTE

STEALING ONE FOR A C-NOTE

We were at an auction among people we knew had a lot of knowledge about fine art. A William Brice (1921–2008) painting came up. He was a California modernist. The pure quality of the painting drew us in. But the front of a painting tells you only so much. If you don’t look at the back, you’re missing a crucial part of the story—maybe even the whole story. In this case, there was an exhibition label on the back. That told us this particular painting was well recognized in its time, which was the 1950s.

No one else noticed. No one else bid. We got it for $100. Now his work is taking off. A well-advised collector would expect to pay in the neighborhood of $20,000 in today’s market for a piece of this quality, subject, size, condition and period.

I have to say, there’s a special satisfaction when you’re with the art mob and you manage to eke one out like that.

People know us and were watching us all auction to see what we were and weren’t bidding on. In this case we kept things very low-key.

A BEAUTIFUL CIRCLE

My husband attended a garage sale and the owner turned out to be friendly with a New Yorker illustrator. She had ended up with a lot of belongings from the illustrator’s estate. The collection was being housed in her garage. At the time, she wasn’t really ready to sell off her trove of illustrations. Our interest never waned.

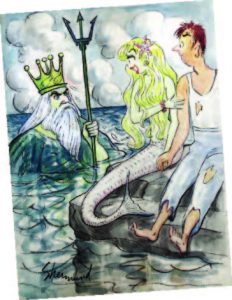

The artist was Barbara Shermund (1899-1978), and she had been on the original team of illustrators for the magazine. My husband put me in charge of the research and inventory process. What a complete pleasure it was. We even had a retrospective exhibition for her witty and wonderful pen-and-ink original images.

We periodically looped back to her. We learned that she had gifted some of the works to her kids. And then, about two years later, we found out her garage had been broken into and also had experienced some minor flooding issues. That was the decisive moment; we convinced her to sell what remained—about 800 illustrations in all.

The Houghton Library Collection of American Illustrators learned about our find and a benefactor purchased more than 100 pieces and donated them to that library at Harvard. Liza Donnelly, a current illustrator at The New Yorker who was writing a book called Funny Ladies of The New Yorker, found out, too. She interviewed me for her very successful book. The artist’s great niece contacted me and wants to write the definitive book on her. There is also interest now from a museum in San Francisco to mount an exhibit of her illustrations.

SMARTPHONES LIVE UP TO THEIR NAME

You’ve found the painting of your dreams. It looks right, the price seems fair, but you’re just not sure. Time to whip out your smart phone. If you are a seasoned buyer, then you are already logged into a subscription service (AskArt costs $100/month) to help you determine its value. If not, don’t underestimate the power of eBay. You’re looking for “completed sales” (they’re in green—don’t look at the red prices—this recently changed). Type in your search words, go to refine, then show more, then sold items. What I like about this is that it shows you the good, the bad and the ugly. Look for the most recent auctions, and take note of any regional differences.

QUICK! WHICH WOULD YOU PICK?

QUICK! WHICH WOULD YOU PICK?

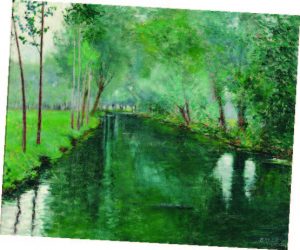

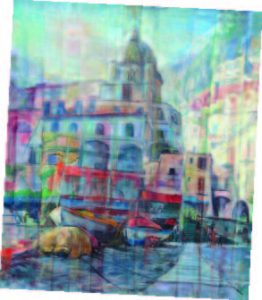

Musicians or Venice? One is wall candy, the other runs into serious dollars. Made your decision? Okay, here goes…

The Musicians painting on the left is what I would refer to as a decorative piece: pleasing to look at, easy to interpret and utilizing only a moderate degree of skill. It’s not a deep image, but it’s light, dynamic and charming, albeit somewhat superficial. The signature is completely indiscernible (this could be intentional) so I cannot look up the artist’s bio or see any type of track record. A closer look indicates materials that would not be considered high-quality or archival (stretcher wood, frame, canvas). In spite of this, it’s an enjoyable decoration, but that is its only value.

The Musicians painting on the left is what I would refer to as a decorative piece: pleasing to look at, easy to interpret and utilizing only a moderate degree of skill. It’s not a deep image, but it’s light, dynamic and charming, albeit somewhat superficial. The signature is completely indiscernible (this could be intentional) so I cannot look up the artist’s bio or see any type of track record. A closer look indicates materials that would not be considered high-quality or archival (stretcher wood, frame, canvas). In spite of this, it’s an enjoyable decoration, but that is its only value.

Venice, on the other hand, is a serious piece by Ida Dengrove (1915-2005)—a trained fine artist who is listed and easily researched. A bio reveals her schooling, exhibitions and many accomplishments. The painting itself employs a beautiful balance of perspective and color values, and is a homage to cubist painters who came before her.

There is a rhythm and an emotional tangibility to the scene. This view of busy Venetian streets is complex. Her deliberate brush strokes evoke a time, a place, a temperature, and so much more. Looking at the “verso” of this painting, you’d immediately see the finer quality materials as well as the labels and notes indicating a serious-minded artist.

This was a great find, and a team effort that turned out to be very profitable. To me, as an art historian, however, the more important piece was that through luck and persistence, I was able to re-open and re-invent an artist whose life’s work was relegated to a suburban garage. Wow. This amazing journey has made me now want to shed more light on other artists from the first quarter of the 20th century. It also got me more interested in illustrations. It was a beautiful circle.

This was a great find, and a team effort that turned out to be very profitable. To me, as an art historian, however, the more important piece was that through luck and persistence, I was able to re-open and re-invent an artist whose life’s work was relegated to a suburban garage. Wow. This amazing journey has made me now want to shed more light on other artists from the first quarter of the 20th century. It also got me more interested in illustrations. It was a beautiful circle.

My first piece of advice to friends and clients who are embarking on this journey is don’t get discouraged before you even get out there. Very good art can slip through the cracks because of generational swings of taste and interest. It can pass down into the hands of a family member who doesn’t appreciate its quality.

And yes, sometimes it’s just sitting there, for no good reason at all, waiting for the average Joe (or Jane) to snap it up for a song.

Unless I beat you to it, of course.

Editor’s Note: The author’s husband, Chris, penned one of our most popular articles a couple of years back: Storage Warrior. Like all of our past stories, this one can be accessed at edgemagonline.com. Rose says he hasn’t shot himself recently with a gun-pen (now you’re curious, aren’t you?). The Myers own Shore Antique Center in Allenhurst.