An award-winning documentarian is leaving his mark on the Lambertville art scene

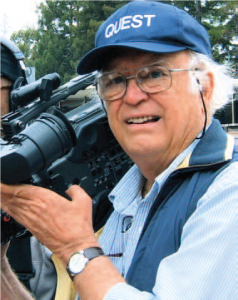

Bill Jersey

How do you segue from a gig as Art Director of the 1958 sci-fi potboiler, The Blob, to become one of the pioneers of the cinema vérité movement? If your name is Bill Jersey, you grab your camera, prop it on your shoulder and never look back. The legendary documentary filmmaker—now a robust 85 and a fixture in Lambertville arts circles—laughs that his Fundamentalist upbringing on Long Island hardly predicted his future stature as a cinematic trailblazer. In fact, Jersey never saw a film until he ran off to join the Navy. He was 17. “The first film I saw was on the USS Arkansas, a battleship that I went on to the South Pacific,” recalls Jersey from his home office along the banks of the Delaware River. “I enlisted in the Navy to get away from home. It was my escape.” The G.I. Bill helped bankroll his undergraduate studies in art. “Studying art in college was the only thing I could do that was acceptable to my parents,” he says. “I couldn’t go to the movies, dance, drink, smoke, swear or play cards.”

After graduation, he put his paint box in mothballs and tested the waters at Good News Produ ctions, a religious film company in Valley Forge, PA. “I told them I didn’t know anything about film,” says Jersey. “They hired me anyway, and I learned how to be an art director. I also realized how little I knew.” So he headed West to graduate film school at the University of Southern California. Graduating in 1956, he dipped his toe in the B-movie drama pool as Art Director of The Blob, Manhunt in the Jungle and 4D Man. But he was primed for documentaries. “There was something about wanting to connect to people in the real world and finding them much more interesting than working with actors with a script,” he says. “If you really care about people, they will know it, and they will open themselves up to you. And that’s what makes a good documentary.”

ctions, a religious film company in Valley Forge, PA. “I told them I didn’t know anything about film,” says Jersey. “They hired me anyway, and I learned how to be an art director. I also realized how little I knew.” So he headed West to graduate film school at the University of Southern California. Graduating in 1956, he dipped his toe in the B-movie drama pool as Art Director of The Blob, Manhunt in the Jungle and 4D Man. But he was primed for documentaries. “There was something about wanting to connect to people in the real world and finding them much more interesting than working with actors with a script,” he says. “If you really care about people, they will know it, and they will open themselves up to you. And that’s what makes a good documentary.”

In 1960, Jersey launched Quest Productions and began attaching his own vision to a slate of industrial films for corporate giants Western Electric, Exxon and Johnson & Johnson. He won his first Emmy Award in 1963 for directing Manhattan Battleground for NBC-TV’s DuPont Show of the Week. Ever the maverick, Jersey never felt compelled to toe the company line. “I don’t do ‘promotional’ films,” he emphasizes. “I found you have to really try to understand the company better than they do. I try to give them what they need, even though frequently they would not describe their needs that way. The only way is by taking the big risk, the hero’s journey, to look at things honestly.” Jersey got a chance to kick-start that journey when he filmed A Time for Burning in 1965. Commissioned by Lutheran Film Associates, the cinema vérité Civil Rights documentary records the failed mission of young Lutheran Pastor  Bill Youngdahl to integrate a large, all white church in Omaha.

Bill Youngdahl to integrate a large, all white church in Omaha.

A Time for Burning tracks the crises of conscience and faith that arose when the minister encouraged his white congregation to engage with black congregants from a neighboring Lutheran church. Despite his gentle, faith-based approach, Pastor Youngdahl’s impact on Omaha’s Lutheran community proved to be, as Jersey predicted, incendiary. “The Lutherans wanted a film about the church and race,” he recalls. “So I found a minister who had an integrated church in New Jersey and was being called to a big al lwhite church in Omaha. I knew he’d want to integrate it, and that there could be some tension. I met with the minister, who said, ‘You can do a film here, there’s no problem.’ And I thought, ‘Well, that’s what you think.’ “Look,” adds Jersey, “the church didn’t need a film about a minister getting kicked out of his church.

They needed a film about how wonderful the church was, and how Jesus was going to be loving to everybody.” Unencumbered by a script, narrator, captions, timelines or media stars and filmed with a minimal crew, A Time for Burning became a benchmark Civil Rights documentary that subsequently received critical acclaim, an airing on most PBS stations nationwide, and an Oscar nomination. It thrust Jersey to the forefront of the cinema vérité movement where he has remained for almost 50 years,  producing and directing independent documentaries on such hot button issues as racism, criminal justice, gang violence, AIDS, Communism and integration. “For me, cinema vérité means letting the truth drive the story,” explains Jersey. “I don’t set out to prove anything— as many documentarians do. The difference between me and others is that I believe in being a participant observer. I explore options with my participants in the belief that our encounters will open them up to seeing more of themselves—not to see themselves as I see them. It’s a tricky business; but in my view, it’s an essential part of being a documentarian.”

producing and directing independent documentaries on such hot button issues as racism, criminal justice, gang violence, AIDS, Communism and integration. “For me, cinema vérité means letting the truth drive the story,” explains Jersey. “I don’t set out to prove anything— as many documentarians do. The difference between me and others is that I believe in being a participant observer. I explore options with my participants in the belief that our encounters will open them up to seeing more of themselves—not to see themselves as I see them. It’s a tricky business; but in my view, it’s an essential part of being a documentarian.”

A Time for Burning continues to be a staple in film schools where Jersey is a sought-after guest lecturer. In 2004, the film was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the prestigious National Film Registry. Despite his résumé of more than 100 films, Jersey—with typical self-effacement—claims to have lost count of the awards and honors he’s received. In the mix are names like Emmy, Oscar, Peabody, DuPont Columbia, Christopher, Gabriel, Cindy and Cine Golden Eagle. Jersey continued in the winners’ circle this spring, garnering a Peabody Award for Eames: The Architect and the Painter. The documentary profile of visionaries Charles and Ray Eames had a healthy theatrical release in late 2011 prior  to debuting on PBS as part of the American Masters series. It should come as no surprise that Bill Jersey—father of five and grandfather of five—has no intention of winding down. “On the contrary, I’m winding up!” he says with relish, as he now juggles two careers instead of one.

to debuting on PBS as part of the American Masters series. It should come as no surprise that Bill Jersey—father of five and grandfather of five—has no intention of winding down. “On the contrary, I’m winding up!” he says with relish, as he now juggles two careers instead of one.

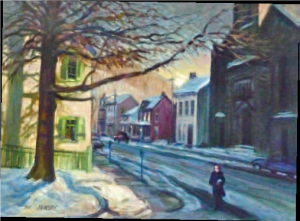

With a new two-hour documentary in the works—The Failed Revolution—about the history of the Communist Party in the U.S., Jersey has also enthusiastically returned to painting. He takes full advantage of the lush natural landscapes in and around his home, a charming 19thcentury boat builder’s cottage in Lambertville on the canal bordering the Delaware River. “We love it here!” he enthuses. “And since my passion is painting, this is a great community to be a part of.” A fan of painter Edward Hopper—“his use of light”— Jersey brings his filmmaker’s eye to his painting: “One of the reasons I like landscapes so much is I like being  out in the country where the light is changing. If you’re painting a river, you’re painting something in motion. The light does not sit there for you. That lovely shadow from the rooftop that you love will be gone in 15 minutes. It’s a very alive process.”

out in the country where the light is changing. If you’re painting a river, you’re painting something in motion. The light does not sit there for you. That lovely shadow from the rooftop that you love will be gone in 15 minutes. It’s a very alive process.”

Sharp and witty with energy to burn, Jersey spent his 85th birthday with his wife, Shirley Kessler, painting in Italy and enjoying his favorite sport—fine dining. He’s quick with a quip when asked if “80 is the new 60”. “Not in the knees,” he laughs, “but in terms of intellect and one’s capacity to engage in meaningful interaction with the world. That’s what keeps me young. Every day I read The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times because those are two perspectives I need to understand the world.” “Life is good!” admits Jersey, the eternal optimist. “With all my aches and pains, I am grateful—that’s the magic word—for every minute of every day!” There are Jersey tomatoes, Jersey Boys and Jersey Devils, but there’s only one Bill Jersey.

All photos courtesy of Bill Jersey

Editor’s Note: Bill Jersey’s paintings will be on exhibit at a one-man show at the Bank of Princeton Gallery in Lambertville, NJ, November 15 through December 15, 2012. A Time for Burning and Eames: The Architect and the Painter are available on DVD. Judith Trojan has written and edited more than 1,000 film and television reviews and celebrity profiles for books, magazines and newsletters. Her interviews have run the gamut from best-selling authors Mary Higgins Clark, Ann Rule and Frank McCourt to cultural touchstones Ken Burns, Carroll O’Connor, Judy Collins and Caroll Spinney (aka Big Bird and Oscar the Grouch). Follow Judith’s media commentary in her FrontRowCenter blog at judithtrojan.com.