No town in America packs more history into one square mile

Thursday, January 8, 1778. Midnight and iron cold. A new moon hides behind scudding clouds. Ice in chunks swirls south in the fast-flowing Delaware River. Out of the northeast, a frigid wind drives all life to cover. It’s a night that begs for shutters firmly latched, for boots resting atop the fender of an open fire, a tot of rum in hand and the family watchdog asleep on the hearth rug. Who would choose to be abroad on such a frigid night?Neither man nor beast.

But in Bordentown, on the river’s edge, a bold scheme unfolds—a scheme hatched to unleash terror in the heart of every Britisher aboard His Majesty’s ships, moored 25 miles downstream in Philadelphia. The contraption, an 18th century version of a 20th century Kon Tiki, consists of dozens of kegs—each packed tight with gunpowder—all lashed together into a crude raft to be set adrift in the icy river. Protruding iron rods hammered into the kegs will, on impact, activate a flintlock, which ignites a spark to detonate the gunpowder. The result: a resounding explosion calculated to send any British ship to the icy bottom of the Delaware River. History books called it the Battle of the Kegs. The redcoats only lost one vessel and four men, but the chaos it created was celebrated throughout the colonies with a popular song.

Bordentown, hard on the banks of the Delaware River, dates back to 1682, when an enterprising English Quaker, Thomas Farnsworth, moved into what was little more than a wilderness. He built a log cabin and a river landing dubbed Farnsworth’s Landing. So began the quiet stirrings of events that, a century later, would prove vital to the triumphant establishment of the United States of America.

“No single community in the state of New Jersey…and maybe in all of colonial America has a richer historical legacy than Bordentown,” so says Patti Desantis, a native of Bordentown and past president of the Bordentown Historical Society, housed in a colonial Quaker meeting-house. “Only one square mile in size, only 4,000 in population, but look at the history that unfolded here!”

Bordentown wears its historical laurels with a becoming modesty that amply reflects its Quaker antecedents. No souvenir stands hawking Colonial bric-a-brac. No tour buses with blaring loudspeakers. No billboards on surrounding turnpikes trumpeting the historical treasures that are Bordentown’s rightful legacy.

Architectural historians find Bordentown a veritable treasure trove of 17th to 19th century houses, still in prime condition, sturdy survivors in an age that prizes, above all else, the wrecking ball and the look-alike strip mall.

Upper Case Editorial Services

Discovery of Bordentown’s treasures is best accomplished by a leisurely one-mile stroll along the old brick sidewalks, shaded by ancient sycamores and maples. Where better to begin than on Crosswicks Street in front of Old City Hall with its Queen Anne clock tower?The Seth Thomas clock atop the tower is dedicated to Bordentown resident William F. Allen, credited with creating order out of chaos in the late 1800’s by coordinating dozens of local times into the single coordinate we call Standard Time.

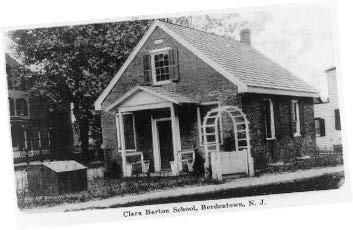

At the juncture of Crosswicks and Burlington stands the simple, gabled schoolhouse, New Jersey’s first public school. It’s the Clara Barton Schoolhouse (above), named for the town resident who founded the American Red Cross. Artifacts of her remarkable life are displayed within.

Photo by Susan Kaufmann, Hidden New Jersey/HiddenNJ.com

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places is the Francis Hopkinson House (right), a three-story architectural gem. A signer of the Declaration of Independence, barrister, poet, musician and scientist—and close friend of George Washington—Hopkinson, after studying at Oxford, returned to the colonies to be the first student enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania. He was a fierce patriot who lent more than a casual hand that frosty January night on which those legendary kegs were launched; he also penned the popular tune that commemorated the event.

PAINT THE TOWN RED

PAINT THE TOWN RED

Bordentown hosts a full calendar of events from May through October, including the Cranberry Festival, which takes place on October 5th and 6th. The festival draws thousands of people and features handmade crafts, original art, a classic car show and a wide range of gourmet and artisan foods. The restaurant scene in Bordentown is always vibrant, as is the shopping in downtown. History buffs are likely to find the city very walkable and decidedly un-touristy. Many visitors opt for a self-guided walking tour; an excellent one can be downloaded at downtownbordentown.com.

An accomplished student of heraldry, Hopkinson, at Washington’s request, designed our nation’s first flag. The stars he took from Washington’s coat of arms, the stripes from his own family’s coat of arms. Philadelphia’s Betsy Ross is credited with having sewn our first flag. But it was designed by Frances Hopkinson and formally adopted by the Second Continental Congress on June 14, 1777, a date commemorated nationwide today by our June 14 celebration of Flag Day.

Photo courtesy of Re/Max Real Estate

Just across the street is the Joseph Borden House (see page 15). It was rebuilt in 1778 after the British stormed and sacked the town, burning the original Borden House to the ground. Borden gave his name to the town where he owned the cooperage from whence came the kegs sent down the Delaware to terrorize the British navy. He also established a vital rail link (right) that provided safe travel from Philadelphia, via Bordentown, to Perth Amboy and then by ferry to New York. It was, in the late 18th, early 19th centuries, in terms of travel convenience, the equivalent of I-95. It also, not so incidentally, made Joseph Borden a very wealthy man.

National Museum of American History

Borden and Hopkinson were friends and fellow activists throughout the American Revolution and its tumultuous aftermath. Both men befriended a young transplant from England, Thomas Paine. At the age of 29, Paine journeyed to the Colonies at the behest of his mentor, Benjamin Franklin. He landed in Philadelphia but soon moved to Bordentown, where he built a house on the corner of Church and Farnsworth. Though radically altered, it is still there. In short order, Paine was publishing and distributing pamphlets entitled Common Sense, which advocated independence from England. His pamphlets were avidly read throughout the 13 colonies. Since such writing was highly treasonous (and carried a mandatory sentence of death by public hanging), Paine published anonymously. In 1777 and ’78, he donated all of his earnings to the revolutionary cause. It can fairly be said that George Washington’s army could not have survived its first six months had it not been for Paine’s financial aid. A charming statue (above) commemorating Paine’s days as a staunch patriot graces a carriage turn-around in a leafy park overlooking the Delaware.

It would be a mistake to think that Bordentown’s historical bona fides rest exclusively with the revolutionary era. In 1813, Napoleon Bonaparte’s older brother, Joseph Bonaparte, named King of Spain by his emperor brother, was stripped of the monarchy by a disaffected populace and forced into exile. Banished from France, unwelcome in England, he found his way to America. Political connections took him from New York to Philadelphia. Amorous connections took him from Philadelphia to Bordentown. There, on an estate called Point Breeze overlooking the Delaware, he had ten miles of carriage paths built and imported countless rare botanical specimens. He built an artificial lake, just right for winter skating and summer dips, and stocked it with French swans. The residence was a wonder of marble fireplaces, sweeping staircases, a vast wine cellar and a library of more than 8,000 books. At Point Breeze, the ex-King of Spain entertained many notables of the day, heads of state, prominent financiers, and internationally acclaimed musicians, authors and artists. With his American love, Annette Savage—fondly known as Madame de la Folie—Joseph Bonaparte fathered two American daughters.

In 1815, when the place was devastated by fire, the townspeople arrived en masse to help salvage as much as possible from the blaze. Reflecting back on that disaster Joseph wrote:

Photo credit: The History Girl/HistoryGirl.com

“Everything that was not consumed, has been most scrupulously delivered into the hands of the people of my house. In the night of the fire, and during the next day, there were brought to me, by laboring men, drawers, in which I have found the proper quantity of pieces of money, and medals of gold, and valuable jewels, which might have been taken with impunity. This event has proved to me how much the inhabitants of Bordentown appreciate the interest I have always felt for them; and shows that men in general are good…”

Of its glory days as home to European royalty, Bordentown today retains only the handsome wrought-iron gates that were the entrance to Breeze Point. Splendid horse-drawn carriages no longer use the lovely turn-around where Tom Paine in bronze stands, pamphlets in hand. Commercial river traffic, once the town’s prime source of revenue, has given way to weekend kayakers, fishermen and mid-summer tubing expeditions. Once a vital hub of colonial transportation, Bordentown is now home base to Ocean Spray Cranberry and corporate headquarters for Prince Tennis Racquets. Yet, as Patti Desantis likes to remind the history-hungry visitors who find their way to Bordentown, it is the town’s lineage, so lovingly preserved despite the relentless pressures of modernism, that makes Bordentown unique among New Jersey’s rich store of tourist attractions.