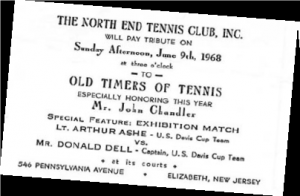

One of the most revered and innovative tennis coaches in the North-east also happens to be the preeminent authority on the culture and history of black tennis. In fact, Arthur A. Carrington Jr. wrote the book on it. Born and raised in Elizabeth, he learned the game at the legendary North End Tennis Club and, in the 1960s and ‘70s, became one of the most formidable players in the American Tennis Association (ATA), the oldest African-American sports organization in the United States. EDGE editor Mark Stewart spent a Sunday morning swapping tennis stories with Art, who received an education at North End that transcended the strokes he perfected there.

EDGE: Growing up in Elizabeth, do you recall how you first became acquainted with the North End Tennis Club?

AC: My mother had introduced me to the North End, but I didn’t really get with it until I was in the fifth grade. A friend of mine moved across the street from the tennis courts and we would come from the playground and see all these black adults and all these nice cars—you know, guys wearing white shorts and playing tennis. Naturally, we were curious and we’d wander over to the club. Well, the members got us involved right away and we started playing. Sydney Llewellyn was out there—he coached Althea Gibson—and he would work with the younger fellows. All the top African-American players from the New York, New Jersey and Philadelphia areas would come and play there. It was quite incredible. It was very busy on the weekends, and in the evenings. In the summertime, me and my boys would play throughout the days.

EDGE: How important was the club to your development as a player and a teaching pro?

AC: I’ve been teaching over 53 years now. Every day, since my introduction to North End, whenever I go to a tennis court, in my mind I’m going back there because it became a safe haven and a place that we could really grow and learn from the kind of adult that was there. We had a small junior program at the club, but we interacted with the adult members tremendously. We had a lot of cookouts in addition to tennis tournaments at the North End Club. I got hooked on the social life as much as the tennis. You never really saw much alcohol, so there was no disruptive behavior. It was the place where you learned about conduct and etiquette. It was a different environment—this is where the black doctors and lawyers and schoolteachers and funeral-parlor directors from all around Union and Essex Counties would come to play and socialize. This was my first exposure to people who we would now call middle-class, that were employed outside of, say, factories or the construction world. This is also where we were introduced to the idea of attending black colleges, such as Howard, Hampton, Morgan, Fisk, Morehouse, Delaware State and Lincoln University.

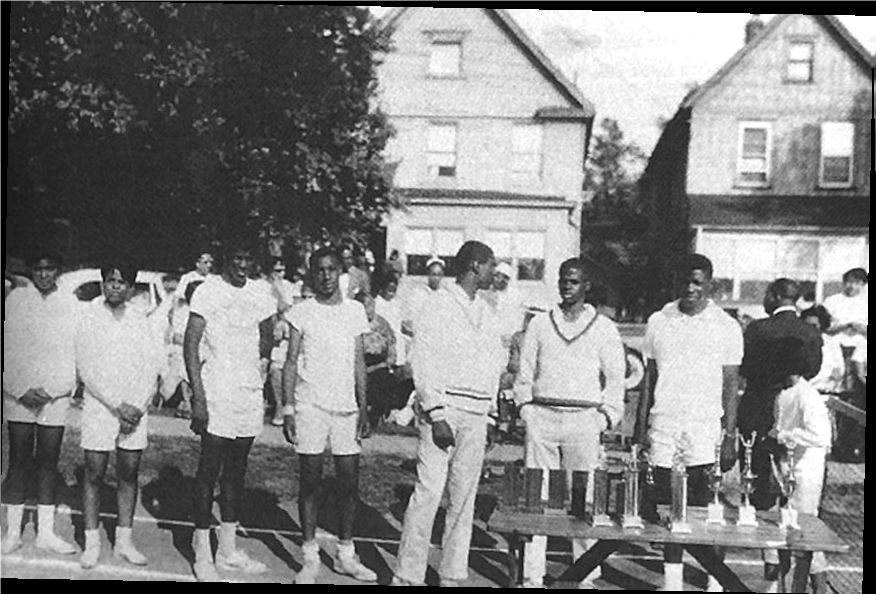

EDGE: What type of tournaments were held at North End?

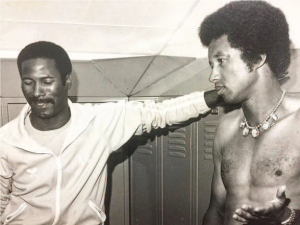

Art Carrington and Arthur Ashe

AC: We would have our little state ATA tournament, which drew people of color who lived in New Jersey. I would see really high-quality tennis players come in. The first one I remember was a guy by the name of John Mudd, who lived in Orange. He was like 17 years older than me, but we later became doubles partners and he was very instrumental in my life—influential as far as tennis and socially. He was an entrepreneur who owned a nightclub in New York and a nightclub in Asbury Park, where he was from originally. He had a topspin forehand and a kick serve—he opened my eyes up to another level of tennis.

EDGE: Did you have other mentors at the club?

AC: Yes, many. One was Dr. William Hayling, a gynecologist who delivered thousands of babies. He was one of the founders of 100 Black Men along with Jackie Robinson. He grew up with Mayor Dinkins in Trenton. I met African Americans from all over the country at the North End Tennis Club and gradually I began to spread my wings. I would go to these people’s houses, where for instance I remember seeing my first finished basement. I mean, I came from good parents—working parents—but this was a step up, financially and socially speaking. This led me to be introduced to their counterparts in the white world. White doctors, white lawyers, and their kids.

EDGE: Describe the location within the context of Elizabeth back then.

AC: North Avenue was a very commercial strip. At one time, around 1900, it was a leading thoroughfare that went from Elizabeth to Newark. There was a doctor who owned a large house and he had the only double lot, which extended all the way back to the next street, which happened to be the start of the black neighborhood. His family sold the house, but the tennis court was sold to the North End Club.

EDGE: What kind of friendships did you forge at the club?

EDGE: What kind of friendships did you forge at the club?

AC: There was a guy name Eddie Eleazer who lived near the club, who was a very good player. We went from fifth grade through Hampton Institute together. When colleges started recruiting me, I would tell them about him, as well as my brother, who was a year behind us and also was very good—he went to Rutgers. Eddie and I graduated from Hampton together and we won all the conference and national black titles together in doubles. There’s nothing like having a comrade, you know what I mean? We were on the same teams together going back to Thomas Jefferson in Elizabeth. He and I and Ron Freeman, an Olympic 400-meter man, formed a partnership that is unbreakable to this day. We all speak several times a week. We used to say, “We are doin’ our thing and movin’ on.” [Laughs].

EDGE: At the other end of Union County was Shady Rest. In what ways did that differ from the North End Tennis Club?

EDGE: At the other end of Union County was Shady Rest. In what ways did that differ from the North End Tennis Club?

AC: Shady Rest was a country club out in Scotch Plains. That was the number-one country club for black people. The people who built Echo Lake built Shady Rest and sold it to black owners in 1921. It had nine tennis courts, a nine-hole golf course and a large dining hall. It had the same kind of people as North End but was much larger. Shady Rest was the kind of place where you’d go to see Count Basie, Duke Ellington and Sarah Vaughan. Segregation made black entertainers go to places where black people socialized. It was the spot. There was nothing else like Shady Rest in the country.

EDGE: Let’s get back to your coach, Sydney Llewellyn for a moment. He seemed like quite a character. Can you paint a picture for me?

AC: I met him when I was 12. He came in from New York and he was always a real smooth dresser. He had his safari suit on with the safari hat—he was dressed to kill. He was the first tennis “pro” I knew, in that he had the tennis pro look, he had the gear, but he was also very cosmopolitan, a very smooth brother. [Laughs] As young urban kids, we loved to listen to him. He came from Jamaica at about 18 years old to New York. He told us he came to America to be a dancer, a hoofer and whatnot. Dancing was like the rap industry in those days. I learned a tremendous amount from Sydney about life and spirituality and family and manhood. He was a tremendous mentor of mine.

EDGE: What is it that made him special as a tennis coach?

EDGE: What is it that made him special as a tennis coach?

AC: He was a purist as far as his stroke production. So he was like Nick Bollettieri—very fundamental.

EDGE: I worked with Nick on a book, by the way, and it was the most stressful year of my life.

AC: [Laughs] I can imagine that. That’s what I’m saying, because when you don’t have a real tennis background, you just pound them fundamentals, I guess. Actually, Sydney did have tennis in his background from Jamaica.

AC: [Laughs] I can imagine that. That’s what I’m saying, because when you don’t have a real tennis background, you just pound them fundamentals, I guess. Actually, Sydney did have tennis in his background from Jamaica.

He had worked somewhere as a young man and had access to a white tennis club, so I suspect he was introduced to tennis in the proper way.

EDGE: After college, you kind of kept the North End club alive. What was happening at that point?

AC: Starting in the 1960s, some Jewish doctors offered their black colleagues an opportunity to come join their clubs for tennis and golf. It was just enough that we lost our leadership, which kind of just filtered away. In the 1970s, we finally gave up our place in Elizabeth. It’s understandable. Everybody wants better facilities. When I didn’t know anything else other than North End, that was the greatest facility. As my game improved and I competed at other clubs, I realized that there were better places to play. After I graduated from Hampton in 1969, I kept North End open in the summertime to run my tennis academy until 1975.

EDGE: What made you decide after college to get into coaching? What new perspective did you feel you could offer other players?

AC: I liked being independent in terms of the business part. Also, I believed in order to coach, to be a good teacher, you need to be your own best student. You’ve got to gain inspiration in order to pass it on. I’ve always believed in whole-body integration, in purely flowing movement. I use rhythm as the special thing that makes the game flow. This has allowed me to be in tennis all these years with no injuries, no rotator cuff issues. I have a nice-looking game. I move with it and I move in a flow. So I teach people how to move properly and to respect rhythmic cycles and sequences, to understand how the body is supposed to work.

EDGE: Has it become harder to get young people to buy into this?

AC: No, because I use martial arts tools and other tools, including music, that are fun in my teaching. So when students go back out onto the court, they are more coordinated. That’s what you need to do in order to be good. I’m a physical education teacher with tennis as a specialty. I think that’s something that is missing from the game. Kids need to have a foundation, phys-ed-wise, that they can use all their lives.

EDGE: It is a rare thing for historians to be participants in the history they cover. While you were coming up as a player at North End—obviously long before you began researching your book Black Tennis—did you have a chance to interact with some of the pioneers from the early days of the ATA, the great champions like Ora Washington?

AC: Yes, I did. They were older people by then, of course. But you know, there were no books that told their story, no place you could go to learn about them. Even many years later that was the case. You hear about Arthur Ashe, you hear about Althea Gibson, but there is almost nothing about the tennis communities that produced them. If you didn’t have the doctors and lawyers and other professionals—backed up by all these progressive African Americans—at facilities like the North End Tennis Club, you might not have had an Ashe or a Gibson or an Art Carrington. That is why I wrote Black Tennis and archived it the way I did. The story is in the community and that’s what people are missing about places like we had in Elizabeth. During the time when tennis was booming with blacks, we were coming from little neighborhood clubs like North End. Most people don’t know about this. They ask me, “How did you get into tennis?” And I’m like, growing up, I thought tennis was a black game! [Laughs] When I first set my eyes on tennis, it was all black people. There wasn’t anything that told me I’m not supposed to do this, you know what I mean? It’s not like I was aware there was a “white” game. I embraced tennis and the people that went with it.

Editor’s Note: Art Carrington was the national singles champion among historically black colleges and universities three times in the 1960s and was the second African-American player after Arthur Ashe to compete in the US Open. In 1972, he played in the ATA singles final, which was the first-ever televised match between black players. In 1973, he was crowned ATA champion. Art says that keeping the history of places like North End alive is “a way of making my own black life matter.” Signed copies of his book Black Tennis can be ordered through The Carrington Tennis Academy, which operates in Amherst and Northampton, MA, at (413) 977-1967.

Editor’s Note: Art Carrington was the national singles champion among historically black colleges and universities three times in the 1960s and was the second African-American player after Arthur Ashe to compete in the US Open. In 1972, he played in the ATA singles final, which was the first-ever televised match between black players. In 1973, he was crowned ATA champion. Art says that keeping the history of places like North End alive is “a way of making my own black life matter.” Signed copies of his book Black Tennis can be ordered through The Carrington Tennis Academy, which operates in Amherst and Northampton, MA, at (413) 977-1967.