Two decades before Al Jarreau gained international fame with his joyous theme from the hit TV series Moonlighting, he was moonlighting as a singer with the George Duke Trio in San Francisco. Jarreau was busy putting his Master’s degree to work as a vocational rehabilitation counselor when he found his stride on stage…or vocal thumbprint, as he likes to call it. Needless to say, he’s never looked back. Editor at Large Tracey Smith asked the six-time Grammy winner to look back—at his musical family, his early influences, and the unexpected twists and turns in a professional career that is now in its sixth decade.

EDGE: What kind of impact did Moonlighting have for you?

AJ: People heard me who had never heard me before. People who were unlikely to go to Tower Records and search through the jazz bin and find this singer named Al Jarreau—who was singing Chick Corea and Dave Brubeck, who was doing this really eclectic form of music that had a mixture of styles. I mention Tower Records because that’s the time period covered by Moonlighting, when we had brick and mortar stores to go into.

Picturemaker Productions/ABC Circle Films

EDGE: Moonlighting had an international audience.

AJ: That’s an important point. People in Jakarta, Indonesia, and Oslo, Norway found out about Al Jarreau by hearing [singing] Some walk by night, some walk by day. Moonlighting strangers, who just met…on the way. It was a very wonderful introduction to people, who went out and found my music. And [laughs] guess what? Listening to me they learned about Dave Brubeck and Chick Corea and found that music, and got their lives enriched some more.

EDGE: How did you get that job?

AJ: The writer called me and he mentioned he was doing music for a pilot show that would star Cybill Shepherd and—I could hear papers rattling…he was looking for Bruce Willis’s name and he finds it—Bruce Willis, this young actor. Who knew!

EDGE: What did you want to be when you grew up?

AJ: My Dad was a preacher, a Seventh Day Adventist Minister—four years of school, ordained ministry, not somebody who read the bible a few times and decided to open a church on 3rd and Vine. So I wanted to be a preacher until I was 13 or 14 years old [laughs]. But then I figured out that probably was not for me. My older brothers had brought jazz and stuff into the house. They sang the Mills Brothers, Count Basie, Sarah Vaughan, Billy Eckstine—they called themselves The Counts of Rhythm. I was knee high to them looking up in total wonderment. That was the heaven I wanted to go to, where they do this kind of music. Impactful! Greatly impactful.

EDGE: When did you start singing?

AJ: When I was four years old. It was a wonderful thing to stand there and open your mouth and something comes out that makes people smile. I got it. Whatever I did, my folks were big on education, so I knew that I would stay in school, graduate from high school and go on to college somewhere. I didn’t know what my vocation would be, but I knew that more education was in my future, and that I would be doing music all the way through. And that’s exactly what happened. All through high school, I sang in the a capella choir, solos that I rehearsed for and looked forward to, doing the sacred music of Bach, the show music of Broadway, singing doo-wop music on the street corner and in the bathroom with three other guys [laughs], because there was good echoing off the tile. I rehearsed with quartets that only sang a couple of nights a year at Lincoln High School—we got together to laugh and smile and make this music we could make with these four people.

Photo by Helmut Riedl

EDGE: Did your father sing?

AJ: My dad sang his butt off! He sang in a quartet that traveled all the states of the Union doing church music. They were all students at Oakwood College and becoming ministers within the faith. My dad was a brilliant singer, an Irish tenor type of voice. My mother was a pianist and she could sing, too. But her main thing was to play the piano, and she played for the choir and with the soloists that sang during most of the years of my upbringing in church.

EDGE: When did you know you shared that gift for music?

AJ: At five or six I knew. I knew I had it—that early! The dream began then to do music in whatever situation I could.

EDGE: How did you establish your voice and perfect your craft?

AJ: Simply by doing it. When you do it over and over, you find yourself. We all begin trying to sound like somebody that we admire and that’s good, but if you do it long enough, you’ll find your own voice. There’s a thumbprint inside you, inside your mind, inside your throat, that is only you, that nobody else has. If you have time to research and look for it, you find your own thumbprint. Don’t nobody sound like Ray Charles or Joe Cocker or Celine Dion.

EDGE: Who did you emulate at first?

AJ: When I started out, I wanted to sound like Johnny Mathis…and Jon Hendricks. Pound for pound, Hendricks is one of the best jazz singers that ever walked the face of the earth. He’s 95 and still doing it. Go and find Lambert, Hendricks & Ross—I wanted to sing like those guys. Most singers who sing jazz don’t sing complex stuff like Take Five, or scat like I do. But I started out wanting to be like Jon Hendricks.

EDGE: When did you start writing your own music?

AJ: I really started writing my own music in about 1969 or ’70, about five years before I recorded We Got By, my first album. It was rather frightening for me. When you listen to Bob Dylan, when you listen to Joni Mitchell, when you listen to Janis Ian—those singer/songwriters who were writing at such a high level, it’s intimidating. So, it took me a while to find my own voice as a writer. I’m still struggling as a lyricist, writing in that way. Musically, it comes out a little more easily for me. But I don’t think I’m a great music writer—I mean, the melody and the chord changes for the melody I do okay. And when I collaborate, that really lifts it to a different level musically. But in terms of the message and the lyrics and all of that…if you read poetry, you see how some people put together words in a way that just [laughs] scares the crap out of you if you’re going to start messing with words!

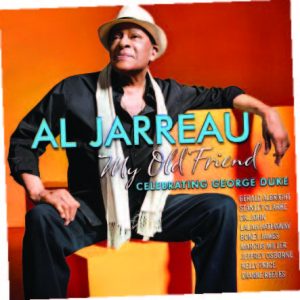

EDGE: Talk about your history with George Duke. Last year you recorded a tribute album to him, My Old Friend.

Concord Records

AJ: [laughs] George and I go back to when we were puppies. I was 24 or 25 and George was 19. There’s a record called Al Jarreau and the George Duke Trio Live at the Half Note 1965. George was not even old enough to be in the Half Note Club! I was doing jazz standards, American Songbook standards and some Broadway music, but George was swinging like Ahmad Jamal and Wynton Kelly—at age 19. I walked in on a Sunday afternoon, which was a “Matinee Sunday,” and stood in line with five horn players and a guitar player, waiting to get up and play with this wonderful trio that was led by George. That started a three-year run with George and me at the Half Note, in San Francisco. His mother would come to the club and shake her finger at the owner, Warren, and tell him to get her son home immediately when he was done performing, because he had to play for church the following Sunday morning. We did a lot of great George Duke music on My Old Friend, with Stanley Clarke, Marcus Miller, Boney James, Jeffrey Osbourne, Dianne Reeves and a bunch of people who came and played on this record. It’s been out there since last August, and its doing great…we’re on the charts since that time and we’ve got numbers, and I’m tickled to death to be doing this summer’s tour with that record under my arms, presenting it basically to the rest of the world. He was one of the most important music people in this sector of the universe during the last one hundred years.