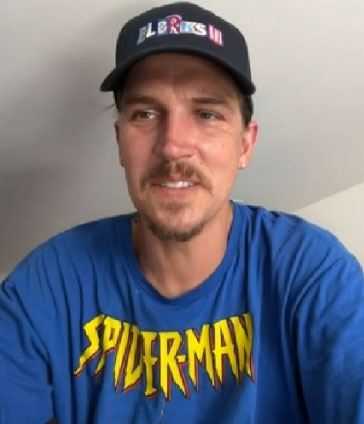

Kevin Smith said that you’ve inspired him in some ways…do you feel you have had a positive effect on his movies and other work?

It’s weird to talk about myself and be like Well, yes, I did this for him, whatever. But I’ve heard him saying that out of his own mouth. He saw something in me, he thought I was funny and he wondered if other people would think I was funny. So he put me out there to see. He says that along the way, I have always been a Yes! person…if he has an idea, I’m never like, “Don’t do that, you’re gonna fail buddy.” I’m like, “Yes!, let’s try it! What can I do to help?” Kevin definitely has great ideas and is super-talented and smart. It’s been a really good team-up.

In 2019, you made your own movie, Madness in the Method. When did you decide you wanted to direct?

It was on Clerks II. Kevin was up in his editing suite and everyone else was ready for the first shot. They were like, “Come on, let’s get going, we’re gonna be late.” Kevin was in the zone and was like, “One more minute.” So I said, “Kevin, let me direct a shot.” I was joking around, but he said, “Go for it.” It was an easy shot, but I got to say Action! and Do it again. I don’t know, man, just right there, I was like, Wow, this is awesome. I’d really love to do this for a full movie.

How did you get Stan Lee to do a cameo?

We worked together on Mallrats, we did an Audi commercial, and I saw him at comic conventions all the time. But it’s not like I had his phone number and talked to him or anything. I did have his assistant’s number, so I called him up and was like, “Bro, I know this is a big ask, but is there any way you think that Stan would be able to come down and we can get him in and out in like two hours at the most?” He called back and said, “Stan told me you have to be done in two hours because he has to go home and eat dinner with his wife. He never misses dinner with his wife.” That was so sweet to me.

At what point were you able to pursue a movie career full-time?

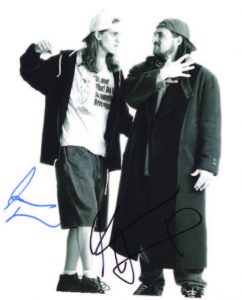

I would say in 2001, with Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back. From Clerks to Dogma, I worked construction, roofing, and delivering pizza. After Clerks, I went back to my normal job, roofing, for a while. And then when we went to do Mallrats, I quit roofing because I was gonna be gone for a couple months and the guy couldn’t hold my job. When I got back from Mallrats, I went to Vancouver and did the movie Drawing Flies. Then I came back and I started doing construction with my buddy. Another buddy owned a pizza place, so he gave me a job delivering pizza. I was delivering pizza and doing construction, like tiling and bathrooms and stuff. After we did Chasing Amy I still did that. It really wasn’t until after Dogma, because that’s when I came to California.

Editor’s Note: This Q&A was done by Andrew Talcott and was edited for length. To read Andrew’s full interview with Jay—and find out how Jay overcame his stage fright—read below!

When did Clerks III begin shooting?

I think it started on Kevin’s birthday last year and we were in Jersey for almost two months. It was awesome, because my wife produces the movies. She’s produced Yoga Hosers, Jay and Silent Bob Reboot and now Clerks III. She runs all the touring and the Convenience Tour and all this stuff with Lionsgate. So it’s great. She came back to Jersey with me and was working producer, and then my daughter came out of course, and my mother-in-law and so the four of us were staying in an Airbnb. It was really cool to be back in Jersey. I have family still in Highlands and we also have our comic-book store in Red Bank.

How did you and your wife meet?

She was going to college at UCLA and her plan was to take a year off and then go to law school. During that year, Kevin was like, Oh my gosh, I need help with this. Can you help me do this? She said sure and did it really fast. Then he kept asking her to help out with other things: Can you book my and Jay’s travel? Can you talk to the venue and see if they can make sure that we have a hotel room? She just did everything really fast and Kevin was like, Wow, I need you to work for me. After like three or four months, Kevin’s like, Hey, let’s open a company together called SmodCo. So they opened the company. But yeah, her plan was never to be at all in any type of entertainment. She wanted to be a lawyer.

When you first shot Clerks, you were nervous about being in front of the camera. How did you overcome your shyness?

I just had to step it up. During Clerks, I was able to get away with needing more time or privacy to feel comfortable. But when Kevin said to me, “Hey, we’re gonna do Mallrats, it’s going to be a studio movie and I wrote a character for you—Jay and Bob are in this movie—but you can’t be like you were on Clerks. Not only can you not do that because, it’s a studio movie, it’s not gonna be just ten of us working on set, like a bunch of friends, putting duct tape around a hockey stick to hold up as a boom mic. There’s gonna be a first AD, second AD, there’s gonna be like forty people on set at all times. You gotta get over this.”

So again, in my head, I was like, I can’t pass up this opportunity. On set, I was [still] nervous, but I was like“ I can’t not do this.” So I sort of just pushed through it and, each day, it got a little bit easier and more comfortable. But honestly, I was nervous throughout the whole movie, but not as nervous—but I still didn’t feel confident. Then I did an independent movie called Drawing Flies right after Mallrats and I was still nervous, but I got a little more comfortable. It just got a little bit more comfortable, more practice, a little easier.

You know the next thing I had to get over? Kevin used to do An Evening with Kevin Smith and he would bring me on stage in front of like 1,500 people and say, “Welcome Jason Mewes!” It was so awesome. Everyone would scream and it was such a cool thing that I loved to do. But then, when I’d get out there, it was like, I was on camera in Clerks again! Someone would go up to the mic and say, “This question’s for Jason. Hey Jason, what was it like filming Clerks for the first time?” And I’d be like… It was good. Kevin afterwards would be like, “Bro, you gotta learn to answer better. Like answer the question, but give a little bit of a story.” It took years to get over that. Thankfully now, you know, it’s been long enough. I do my own A-Mewesing Stories. It’s interesting to go back and think it took four or five movies for me to get comfortable in front of the camera where I didn’t get nervous anymore. And it took me being on stage at least twenty times in front of an audience before I started feeling comfy, answering a question with a little bit of a story and not just being like, Yes. No. It was great.

www.istockphoto.com

Doctors and patients can do more to recognize IPF… an elusive disease that literally takes your breath away.

Three years ago, very few people gave serious thought to the health and function of their lungs. As a result of the Covid pandemic, the public gained a profound appreciation for these vital organs. It is one thing to suffer a heart attack or contract a long-term disease, or even to be the victim of an unlucky accident. It is quite another, however, to be unable to breathe. It is truly terrifying.

www.istockphoto.com

As a pulmonologist, I see patients every day struggling with a variety of breathing issues. Some are curable and others manageable but, unfortunately, some do not have a good long-term prognosis. One in particular is of what happens to the lungs in patients that suffer from Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, or IPF for short. Fibrosis means that the lungs are getting thick and hard. To understand, think of an individual breathing in and out with a normal lung. That lung is like a sponge—you can squeeze it and it comes right back. No problem. Now imagine that sponge is thrown in the backyard for a couple of weeks—and think about how hard and stiff it would feel when you squeeze it. That gives you an idea of what happens to the lungs in patients that suffer from Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The number of patients officially diagnosed with IPF suggests it is an exceedingly uncommon disease. There are as many as 132,000 cases in the US, with 50,000 new cases diagnosed annually. The fact is that, because the symptoms are not specific, IPF can be mistaken for other more common diseases, such as COPD, which means the actual number of cases is likely much higher. IPF commonly goes undiagnosed, often for many months to years. If the possibility of IPF is overlooked on the initial visit, it takes three to five doctors before the correct diagnosis is secured.

Which is a problem, because IPF patients are living on borrowed time. From diagnosis to death, they may only have five years.

What complicates the situation is that the symptoms of IPF are not specific. They include a cough that is dry and non-productive, as well as increasing shortness of breath. However, if a doctor examines patients with the possibility of IPF in mind, there are several signs that can point towards the appropriate diagnosis. They include clubbing of the fingers, Velcro crackles and acrocyanosis—a bluish discoloration of the extremities—among others. More on these symptoms later.

It is a lack of awareness of signs like these that causes a delay in the diagnosis, which is why I have devoted a great deal of time toward raising awareness among healthcare providers and the public of IPF.

Slow and Insidious

Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) encompasses a diverse group of conditions that cause lung fibrosis. There are approximately 150 different diseases that are part of ILD, one of which is Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. These are fairly rare diseases—so much so that most doctors do not always think of them. When patients are referred to doctors with shortness of breath and cough, those patients will be diagnosed most likely with COPD, bronchial asthma, or chronic bronchitis. That translates into thousands of people who go on living their lives while they are actually dying from IPF, believing they have something else. The fact is that many doctors do not think of IPF when the disease might just be staring them right in the face.

IPF is slow and insidious. It usually begins with a cough or increasing shortness of breath to the point where patients realize that they cannot do the things they’re used to doing, such as walking a few blocks or going up a staircase. That’s what triggers the initial physician visit. If there is a history of smoking, COPD is the immediate suspect and the IPF diagnosis may be missed in that critical initial visit.

IPF occurs more frequently in men than women, typically in the later years, after age 60. IPF patients tend to be, or have been, smokers; they have been ignoring what they believe is a “smoker’s cough.” When healthcare providers listen to them with a stethoscope, they don’t really hear anything. Often they figure it is bronchitis, prescribe them an antibiotic, and that’s it.

Eventually, a patient’s persistent, repetitive cough does not improve and the shortness of breath gets noticeably worse…that is when doctors will start looking for other, less-obvious causes.

The unfortunate thing, as mentioned earlier, is that patients might see several doctors with the same symptoms before they are correctly diagnosed. It takes time before the patient is sent to a specialist, and not all specialists are focused on making the diagnosis. Pulmonologists are trained how to diagnose and treat IPF; they are your best bet for getting to an appropriate diagnosis.

Why is IPF so elusive? One reason is that the signs and symptoms are non-specific, and because of all the different diseases that can present similarly. Consequently, in its early stages, some symptoms of IPF may look like other conditions. It is important for doctors to have an open mind and consider the diagnosis of ILD and pursue a differential diagnosis that will lead them to the diagnosis of IPF.

IPF Clues

There are clues that doctors can look for that will lead them down the path toward an IPF diagnosis. The most important is the cough. It is a cough that is dry, non- productive and repetitive. That cough is the most common presentation. The others, as mentioned earlier, are increasing shortness of breath and the inability of Also, when I listen to a COPD patient’s lungs, I hear distant sounds, diffuse rhonchi or expiratory wheezes. By contrast, in IPF, I hear those Velcro crackles—that distinct sound similar to when you separate one piece of Velcro from another. patients to exert themselves as they had before. COPD, by contrast, usually has a cough that produces phlegm.

Other clues I look for include a patient who may be breathing faster than normal and, sometimes, when I look at a patient’s hands with IPF I may observe a rounding condition of the nails called “clubbing.” Also, I may observe Raynaud’s phenomenon, where their fingers feel cold and are discolored. In patients with scleroderma, one may see “sausage fingers.” All of these can be associated with ILD, although they are not exclusive to the disease.

Surprisingly, chest x-rays are not very helpful in diagnosing Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The ideal test is a non-contrast high-resolution CT scan. It can provide doctors with some clues that are otherwise difficult to detect, including honeycombing, subpleural reticulation and traction bronchiectasis, which is a “pulling” on the bronchi. If I see those three things in a CT scan, chances are a patient has IPF. Needless to say, it is important that a radiologist knowledgeable in ILD is looking for these signs, too. We are also encouraging pathologists to recognize signs of IPF when an open lung biopsy is done, because that is not always the case.

Unfortunately, there is no cure for IPF. However, in some cases, we can consider lung transplantation. For a variety of reasons, the number of transplants is very small, including the fact that many IPF patients are elderly and they might not have the strength to survive a procedure like this, or because the disease has progressed too far. Also, there is a shortage of donors. In my practice, we’ve been working with different medical centers on lung transplants. Recently, I have had patients receive transplants at Temple University in Philadelphia; Mt. Sinai and NYU Langone in New York, and Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, where I have been working closely with Dr. Joshua Lee. For many diseases, a major issue in treatment, is that patients wait too long to go to the doctor. For the most part, this is not the case with IPF. I cannot stress enough that Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a disease where, the more closely a doctor looks, the more a doctor will find. The lack of awareness across a broad spectrum of disciplines—including primary caregivers, radiologists, pathologists and others—makes this diagnosis elusive. It is incumbent upon us to recognize IPF when we first encounter it because, for these individuals, the clock is ticking.

Finally, if you are a patient who has been told you have COPD and you are not satisfied with that diagnosis, seek another opinion. If your condition persists and you’re not getting better, get someone else to look at it. Sometimes a pair of different eyes can make all the difference.

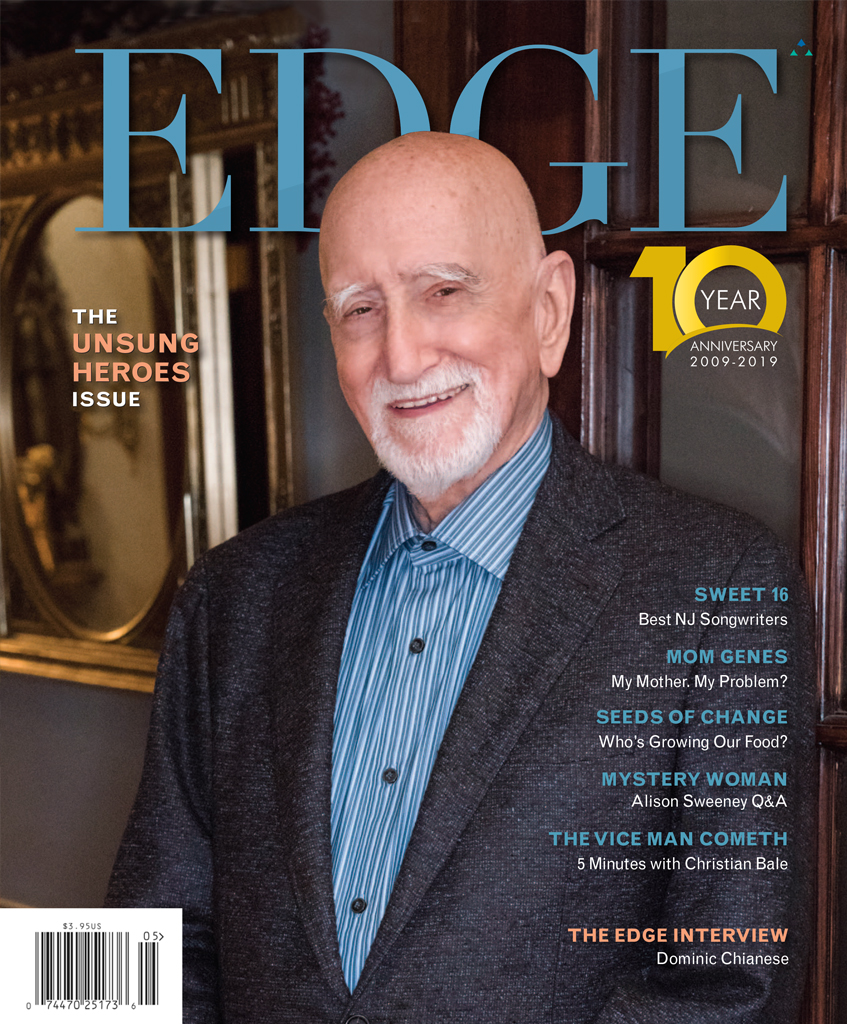

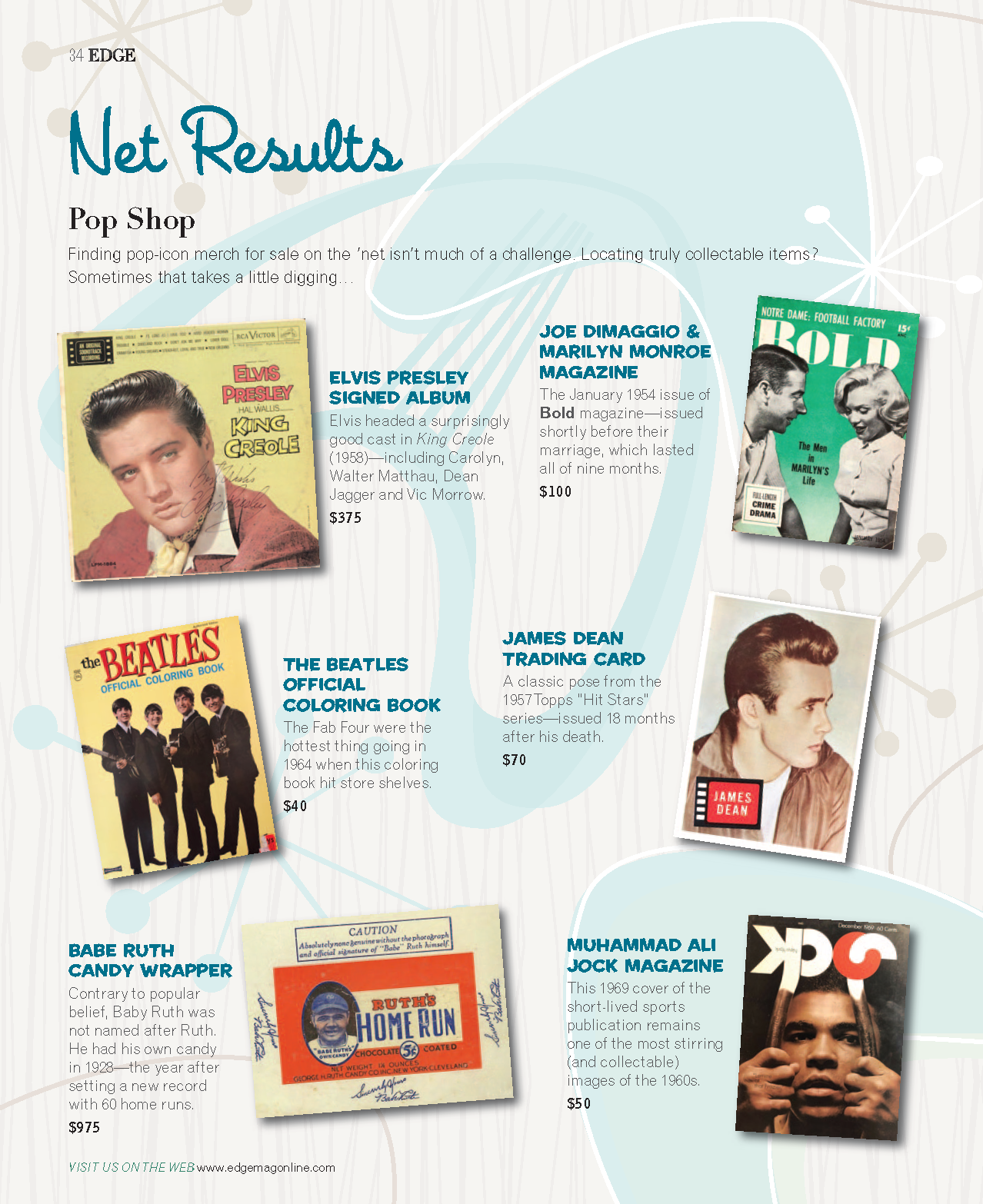

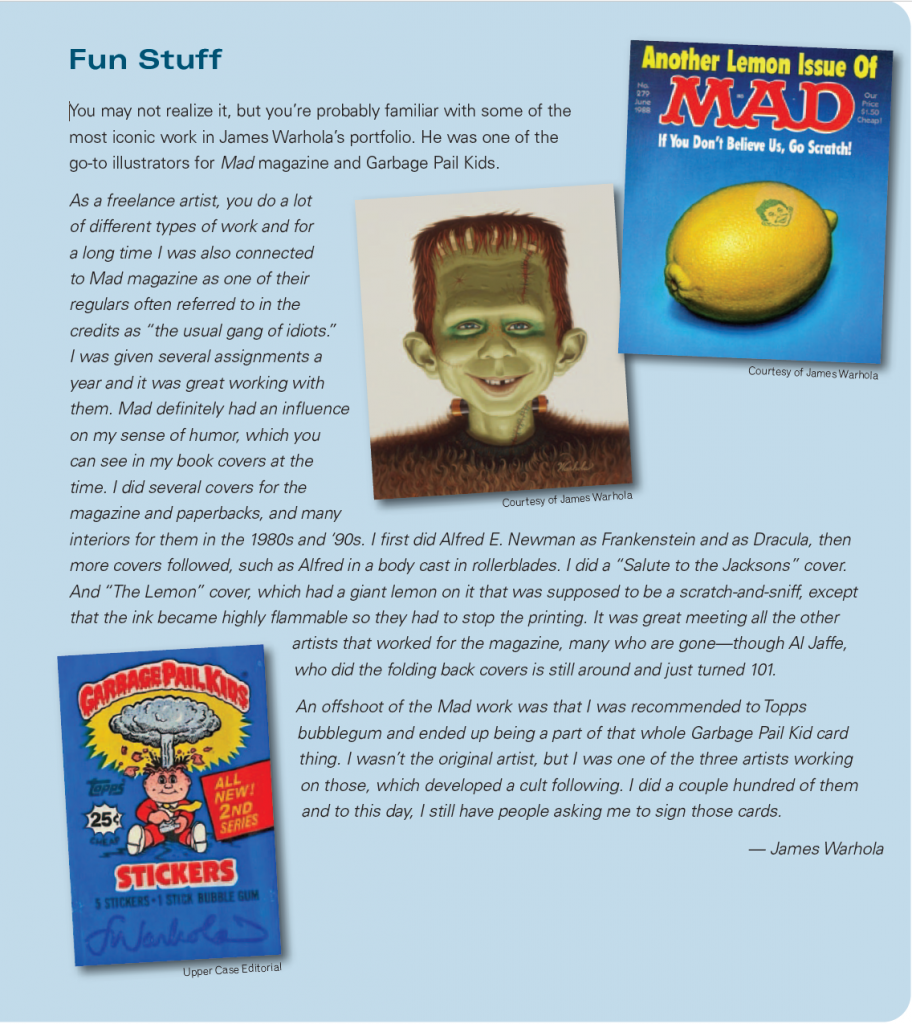

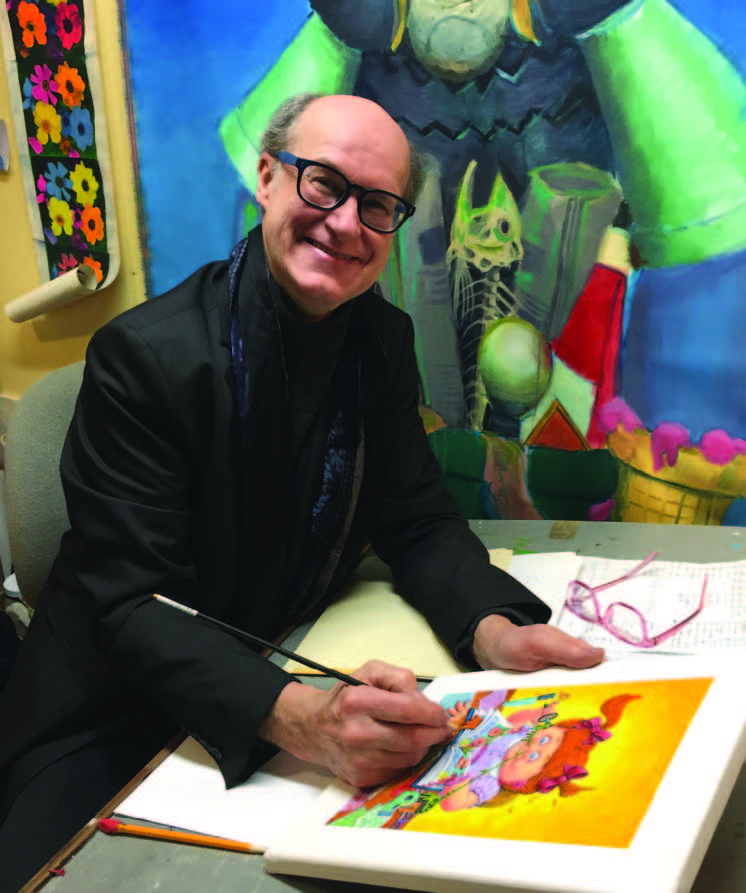

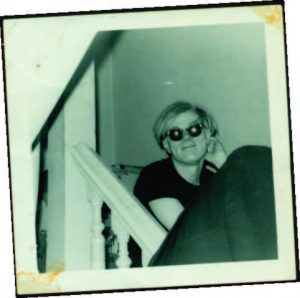

Andy Warhol was a lot of things to a lot of people. To artist James Warhola, he was Uncle Andy. During a career that stretches back four decades, Warhola has been celebrated for his technical mastery, fertile imagination and sly sense of humor. Are we seeing a pattern here? After creating hundreds of covers for popular science fiction titles, he wrote and illustrated a best-selling children’s book about his boyhood visits to his uncle’s New York City studio and home. EDGE editor Mark Stewart sat down with Warhola to find out more about this unique window into the life of a Pop Art icon, and how James found his own niche in the “family business.”

EDGE: What are your memories of the early interactions you had with Andy?

JW: When I came along in 1955, my uncle was already working in New York as a commercial illustrator. I knew him as kind of a bit of an odd creature, living outside the family, who was not like my working-class relatives employed in steel mills and scrap yards around Pittsburgh. His mother, Julia, my grandmother, raised Andy and his brothers in Pittsburgh, but she moved with him up to New York. It was a disconnected situation for me because I couldn’t picture my father having this younger brother who was a very creative, unique individual—into all sorts of great things. I aspired at a young age to be an artist like my uncle. He was illustrating all sorts of things—shoes, appliances, record albums. It just seemed like a wonderful world to get into.

EDGE: Were your parents behind this plan?

JW: Knowing that he made a really good living at it, they were very supportive. Ultimately, I ended up going to Carnegie Mellon University—which used to to be called the Carnegie Institute of Technology, which is where my uncle went. I had a few of the professors that had taught him and they always had “Andy stories.” Apparently, he left quite an impression on his teachers and fellow classmates in college.

EDGE: This was in 1946, right after the war ended, and all these GIs were coming back to school. I’m trying to picture a class full of soldiers and teenage Andy Warhol, and it’s not easy.

JW: Yeah, he was a youngster next to his classmates. And yes, exactly, that first year was difficult for him. He almost was kicked out of school because they had to make room for these vets who were coming back from the war on the GI Bill. Andy was maybe three or four years younger. But he made up a few of his courses during that summer and they allowed him to stay. He ultimately became kind of a star amongst his fellow students. I’ve had the good fortune of talking to many of his classmates and they were just in awe of his ability. He was a little awkward and shy, but his work spoke for itself.

EDGE: Earlier, you mentioned shoes. I covered the footwear industry in my early days as a journalist and people would always say to me, “You know, Andy Warhol, started in this business.” He must have made an impression on the people in that business, too.

JW: Oh, yes. In fact, his very first job was for Glamour magazine—a story titled “Success is a Job in New York” At the beginning of the article, there were a few shoes that needed to be illustrated which he did in a very realistic way. But in the rest of the article his illustrations were kind of whimsical, with these types of young women climbing ladders.

EDGE: What was different about his commercial work?

Courtesy of James Warhola

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: He had this technique which he started in college, called the “blotted ink technique.” He would basically use pen and ink on paper and then hinge another piece of paper to it that he would blot with. The blotted image that had an irregular line became the final art.

Art directors just loved that spontaneous style. It was almost like it was printed, but quite accidental at times, and he got a reputation for it. Lo and behold, one of the upscale women’s shoe companies called I. Miller, which had several stores in the city, contracted with him to do their New York Times advertising. He was able to represent shoes, which were basically boring if they were photographed, in a way that made them look very sleek and wonderful in the advertising. I always felt that the 10 or 12 years he spent in the commercial world was the ultimate graduate program. It was a really great experience. He learned how to work with people, a lot of whom were great art directors and designers. He learned a lot about color, about promotion and how to be noticed amongst the crowd. He caught on really quickly. I never heard of any art director or designer that did not like working with my uncle. A lot of times, he would come in with not just one illustration, but with three or four for them to pick from, which was kind of unheard of at that time. Whether people realized it or not, he was elevating the everyday to the mundane.

EDGE: It sounds like it prepared him well for what was on the horizon.

JW: Yes, I guess it was his training ground for that approach to his art. He was perfectly groomed to be one of the top pop artists of the day. There were several—Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, James Rosenquist—quite a group that started all about the same time in the early 1960s. They were all working in the same vein, pushing imagery of the popular culture of the time. But my uncle was the one as I said, perfectly groomed to know what he was doing. He was truly plugged into that world.

EDGE: What did Andy’s rise to fame in the early 1960s look like through the eyes of a child?

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: I was five or six years old when he moved with Julia from his rented apartment on 35th Street to a beautiful townhouse uptown on 89th and Lexington. It had a lot more room and, at that point, he started experimenting with doing fine art canvases that were related to his commercial product drawings—only more experimental, more spontaneous—imagery of refrigerators, typewriters, windows, telephones and canned fruit. In the beginning, they were kind of loose and drippy. He thought that being expressionistic was making it more artistic. These were his early “pre-pop” paintings that he thought was the direction to go. At some point, he shifted to doing them more cleanly—somebody actually recommended that the drippiness wasn’t necessary—but the idea was still to use the images from advertising in his art. So then, like in 1962, he started doing these clean images of soup cans, which were hand-painted; he hadn’t quite discovered the silkscreening process yet. I didn’t quite understand where he was going with it. It was different. The images were blown up on the canvas using an opaque projector. I remember as a boy his using that projector, which I inherited and used in my field when I was going into illustration. It was soon after that he discovered that silkscreening images was better, so there at his townhouse he experimented doing multiples.

EDGE: What do you recall about of your time with him on your New York visits?

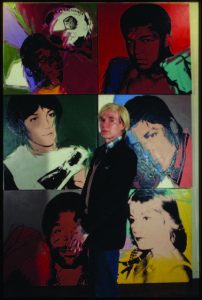

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: I used to love watching him draw. It was like magic. His hand would dance around the paper. He practiced using a ballpoint pen and he had these 16” x 20” pads and he would just fill them up with drawings. I think it was his way of keeping his talent, keeping his hand going. But he did thousands of “practice” drawings. They’re all wonderful and a lot of people who know him from his silkscreens don’t realize that he actually was a really incredible draftsman. I remember wanting to be like him in that way, being a good draftsman. When my siblings and I would visit from Pittsburgh, we often saw him paint. He’d let us watch and sometimes he would give us little chores to do while he was painting. I thought it was quite an exciting time. I mean, of course, he was special to us. He wasn’t really famous at that point, but he was famous to us. He lived in this strange place that was so different and we were all captivated by him.

EDGE: So I have to ask…are there silkscreens hanging in museums that you had a helping hand in?

JW: We did help him by holding the frame so he could pull the paint through. That was when he was doing the smaller silk screens, for instance the Coke bottles, the Fragile labels, the little ones of Elvis and Natalie Wood, in his small studio room. So, yeah, those early silkscreens were done at home. In fact, the early Marilyn Monroes are the ones that have “mistakes.” Some of them have a lot of ink. Some of them have hardly any. Silkscreening is not an easy process. The ink very often has a powerful smell to it and it dries really quickly. So you have to clean the screen out continuously, otherwise the image gets lighter and lighter. If you look at the early silkscreens he did in 1962, those are full of mistakes. To me, my favorite works of art that my uncle did are those early silkscreens of ’62, because I can just picture him working at home doing the best he can.

EDGE: When did he start working in a studio that was separate from the townhouse?

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: He wanted to do large silkscreens of Liz Taylor and Elvis Presley and he couldn’t do them at home, because they required much more space so in 1963 he had to get an outside studio and an assistant. Nathan Gluck continued to help him with his illustration assignments at his home studio and Gerard Malanga was hired to assist with the large silk screening at the firehouse studio he rented two blocks away.

EDGE: In what ways do you think you were inspired or influenced by your uncle?

JW: I was inspired by the fact he was an artist and he was an illustrator. But as far as being a fine artist, I didn’t quite make it to that point. I was too much of a traditionalist, I think, and because of my upbringing, I had a totally different viewpoint. I was part of the television generation starting in the 1950s and ’60s. I didn’t quite understand the creative avant garde aspects of what my uncle was doing. So he didn’t really have that great of an effect on me, although he did support what I was going through. When I told him I was going to study at Carnegie-Mellon, he thought it was great idea.

EDGE: Did he offer any advice at that point?

JW: He thought that I probably should go more into photography than illustration. He believed that illustration was a dying art in the 1970s—that they were using much more photography. And he was right about that. The Golden Age of illustration from the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s was kind of going bye-bye, and they were using a lot more photography. So the available work for an illustrator was more in book publishing, which is where I ended up.

EDGE: You were one of the most prolific sci-fi cover artists of your era. How did you get into that genre?

JW: I had this interest in science fiction and fantasy, being that I grew up with comic books and watching science fiction movies. So I had an idea that I’d go into illustrating books that were science fiction-oriented. And that’s what I did for many years. I illustrated a lot of well-known authors and did three or four hundred covers. I loved reading the books and envisioning some important part of the story to put on the cover. Then the opportunity came up to do children’s books and that kind of opened up a whole new area for me. Instead of illustrating just the one cover that represents a whole book, I would illustrate the entire story, which is a lot more satisfying.

EDGE: What was the actual process for creating a cover that sells?

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: I would get a big, thick raw manuscript. I’d read it over a few times, pull out details and come up with some thumbnail sketches. I would show those to the art director, the art director would go to the editor, the editors would discuss it, and then they’d get back to me with suggestions—or they might like one that’s going in the right direction and give me the go-ahead. I never spoke to the writers. In fact, the process was always that the editors and art directors purposely kept the writer and the artist separate. So we would start with sketches of multiple cover ideas and then I would do one they liked in color. I kept to an organized process so I wouldn’t have to do any kind of corrections in the final art. Since I worked in oil paints, it wasn’t an easy thing to correct. Of course, you wouldn’t want to give away any details in the story that would ruin the ending, but you wanted to pick a climactic moment. I mean, if there was a dragon in the story, you’ve got to use that dragon somehow—also, personally, I loved doing dragons.

EDGE: What set you apart from other artists in the sci-fi/fantasy world?

JW: Over the years, publishers discovered that I was really good at doing covers that had a sense of humor. If there was some kind of humorous aspect to the story I could capture, I loved that aspect. I kind of got a reputation for that. I used to do these books by Spider Robinson who wrote stories about a futuristic bar room with all these crazy alien creatures in them. So, I usually did these scenes for the covers.

EDGE: Did any of your covers become movies posters?

JW: No, not specifically. When a book is turned into a movie, they’ll usually eliminate the illustrated cover and use a photograph from the movie. Like, I did Robert Heinlein’s Starship Troopers and sure enough they came out with the movie, so they republished the book with the lead actor on the cover, my original illustration was kind of jettisoned. I did do the very first cover for William Gibson’s Neuromancer, which became a groundbreaking science fiction book. It delved into the whole computer world and was the first of its kind, known as Cyberpunk. They only published a few thousand copies at first, but then it ended up winning the Nebula Award that year in 1985, which is the big science fiction award. It was never made into a movie, though it was attempted.

Courtesy of James Warhola

EDGE: I recently unearthed some articles I wrote in the 1980s and thought, “Wow I might actually hire this guy!” Do you look back at the early work you did coming out of Carnegie-Mellon and the Art Students League in New York and feel positive about it?

JW: I’m quite impressed with it, actually, because the detail and amount of time I would put into my paintings was so beyond what I’d have the patience for today. I guess it’s just the gradual evolution of an artist who becomes a little more impressionistic. But I quite often marvel at the amount of detail that I used to work with, and the patience. I tell you, that’s quite a gift at a younger age. It’s hard to recapture that.

EDGE: It’s the energy of youth…

JW: Yes…and sticking with a painting! I mean, I can remember sitting at an easel, probably for 16 hours straight, taking a quick break for a bite to eat, and just plowing through all the work that would be required to paint every little creature in those covers. And then, quite often, you’d pick something out and have to repair it or repaint it.

EDGE: As you mentioned, you’ve done a lot of work in children’s books, as both an illustrator and a writer. How did that come about?

JW: Initially, an art director came to me with a manuscript, The Pumpkinville Mystery and said, Try this.

Of course, the whole project didn’t pay as much as a book cover—it was a lot less money and a lot more work, so I kind of resisted at first. But then I did give it a try and liked the result—and everybody else that I did it for liked it, too. So they continued to give me book projects to do. Mapping out a whole children’s book is fun because you’re actually showing the plot and the climax as you come to the end. I have to say, it’s one of the most creative areas that an illustrator can work in. There’s not one type of accepted style, like in the paperback market, where you had to be kind of photographic and couldn’t be cartoony. But in the children’s book area, you can be anybody you want. I like that flexibility. At some point, I was encouraged to try to write my own stories, because if you write and illustrate your own story, you get the full royalty if the book sells well.

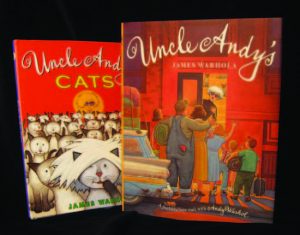

EDGE: Which brings us to your Uncle Andy books.

Courtesy of James Warhola

JW: The first book that I authored as well as illustrated was Uncle Andy’s: A Faabbulous Visit with Andy Warhol. It was about my visits with my family to my uncle’s and grandmother’s house in New York City at a time when he was producing all that early pop art. It was also a window into my uncle’s homelife. Most people didn’t realize that he lived with his mother and had two brothers with large families that would occasionally show up unannounced. It was kind of fun to enlighten the world on his personal life. At one point, my uncle had a lot of cats. They were all Siamese cats and they paraded throughout the house for several years. Everybody saw the cats in the first book and they said, Oh, you gotta do a book about the cats! So I did Uncle Andy’s Cats, which was very enjoyable.

EDGE: Do you think of yourself as coming from an “art” family?

JW: Yes, I do in a way. From an early age, thanks to my uncle Andy, I felt that I that I was a part of the art world. And now my daughter, who’s 25, graduated a few years ago from Cooper Union and she has this obsession with being an artist herself. She doesn’t want to be an illustrator—she saw the pain and agony that I’d go through with my strange books—so maybe the fine art aspect skipped my generation. But, yeah, I definitely feel I’m part of an art family. And I think that my grandmother, Julia, played a significant part in that. She felt there was an artistic aspect to everything—a beauty, whether it’s visual or just an idea. She connected with her kids, who then connected to us. My grandmother was a very creative person. She liked to sing and dance, she did all kinds of art and sewing projects. She brought this belief directly from the “old country,” the Carpathian Mountains in eastern Slovakia, that you could create something different from anything. She emphasized this to her grandkids and I think that’s what I’ve been inspired by. She was a very unique individual who was the one person most important in nurturing my uncle Andy’s creative abilities.

Editor’s Note: In the off-the-record part of their conversation, Mark Stewart and James Warhola found they had something in common beyond the children’s books each has written. In the late-1970s, both studied at The Art Students League on 57th Street in New York.

Museum people like to say they eat and sleep their jobs.

Meet someone who actually does.

The folks who look after New Jersey’s historical structures and small museums have much in common, starting with their daily routine. They arrive at work each morning, walk up to the front door, turn a key, and then ready themselves for the day’s steady stream of visitors. One notable exception is Katherine Craig, who is in charge of the crimson-shingled mid-1700s structure located on East Jersey Street in Elizabeth.

In her case, the unlocking happens from the inside. Because Katherine Craig actually lives in Boxwood Hall. And in the museum world, this makes Craig decidedly uncommon.

Although Craig performs the typical, day-to-day duties of a curator—arranging displays, designing new exhibits, conducting tours and lots and lots of paperwork—her official title is caretaker. Because Boxwood Hall is nearly 300 years old, the state requires that someone with an intimate knowledge of the house make note of (and if possible take care of) any necessary repairs—full-time, around the clock. “It is like living above the family business,” she says. “Living here makes it possible to know every nook and cranny of the house.”

This arrangement makes Craig the most-qualified person on Earth to educate people about Boxwood Hall, from groups of wide-eyed elementary schoolers to day tourists to hardcore history junkies. Not surprisingly, she has become quite adept at tailoring her tours to the age and interests of her visitors. A group of architects came just to study the building’s original door hinges and support beams, which naturally she knew plenty about. “They could give two pins about the Revolutionary War, and that’s okay!”

Craig studied biology at Rutgers before becoming a tour guide at Sandy Hook National Park. When presented with the opportunity to serve Boxwood Hall as its full-time, live-in guardian, her first thought was, I can do that!

The Rest Is History…Literally

Vinny Fleming

Impressed by the long list of prominent and influential Americans who lived in and visited Boxwood Hall, Katherine Craig applied for and got the job in 1981. She was also intrigued by the ways in which Boxwood Hall changed with the times, putting on different faces to preserve itself and its legacy, and decided to turn its evolution into storytelling opportunities.

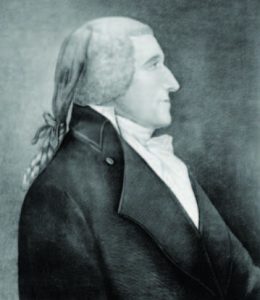

The earliest chapter of Boxwood Hall’s story dates back to 1750, when it was built for 40-year-old Samuel Woodruff, one of 13 children born to Captain Joseph Woodruff, who moved from Long Island to New Jersey as a young man and settled in current-day Cranford. At the time of construction, Samuel was serving as the second mayor of Elizabeth (then known as Elizabethtown), an office he would hold for 14 years. Upon his demise in 1768, Samuel passed Boxwood Hall to his son, John, who in turn put the property up for auction, in 1768. By this point, Elizabethtown had become a well-established and prosperous city, with a population of perhaps 2,000 people. The prestige associated with owning one of the most important homes in one of Colonial America’s most important towns had particular appeal to the winning bidder, a 28-year-old lawyer named Elias Boudinot (above).

The Boudinots, a Huguenot family that fled religious persecution in France in the 1680s, had built an impressive fortune as merchants and silversmiths. Growing up in Philadelphia, Elias was a neighbor and friend of Benjamin Franklin. However, Boudinot business interests had not fared well in the 1760s. Elias figured that buying Boxwood Hall was a prudent first step on the way to rebuilding his family’s reputation. Little did he suspect how prominent the Boudinot name would soon become.

Elias was already moving in impressive circles. He had studied law at Princeton under Richard Stockton, who would add his signature to the Declaration of Independence a few years later. Stockton was married to Annis Boudinot, Elias’s older sister. Elias, in turn, married Hannah Stockton (left), Richard’s younger sister. Elias and Hannah’s daughter, Susan, grew up to marry William Bradford, George Washington’s attorney general. When Bradford passed away in 1795, Susan moved back to Boxwood Hall. Elias, Hannah and Susan lived together in the home for another decade before moving to South Jersey.

By then, Katherine Craig points out, Boxwood Hall had already seen quite a bit of history.

In 1772, an ambitious teenager named Alexander Hamilton enrolled at the Elizabethtown Academy and lived with friends of the Boudinots, Susannah and William Livingston. Like Richard Stockton, William Livingston—a future Governor of New Jersey—would also lend his signature to the Declaration of Independence. Hamilton was a frequent visitor to Boxwood Hall, which was fast becoming a hotbed of revolutionary activity.

Elias Boudinot aligned himself with the American revolutionaries and, once the shooting started, used his wealth and influence to encourage enlistment, procure supplies and support a network of spies. General Washington tasked Elias to oversee the Continental Army’s prisoner situation and commissioned him as a colonel. In 1781, when the outcome of the war was very much in doubt, Boudinot was appointed as a delegate to the Continental Congress and, in 1782, was elected as the body’s president for a one-year term. Under the Articles of Confederation, the position was mostly ceremonial, however his time in office was notable for being America’s first peacetime president.

After the Articles were replaced by the U.S. Constitution and Washington was named President of the United States, Washington stopped at Boxwood Hall before boarding a special barge that transported him across the river to New York for his inauguration. Following three terms in the US House of Representatives, Boudinot was appointed by Washington as Director of the US Mint—an appointment that may have been influenced by his relationship with Alexander Hamilton.

Following the Boudinots’ departure in 1805, Boxwood Hall came into the possession of retiring Senator Jonathan Dayton. Dayton had succeeded Boudinot as a US representative and also served as US Speaker of the House. Dayton was a friend and classmate of Alexander Hamilton at Elizabethtown Academy and almost certainly spent time in Boxwood Hall as a young man. Elias Boudinot and Jonathan Dayton had something else in common: both claimed sizeable real estate holdings in Ohio. In fact, the Ohio city of Dayton was named for the third owner of Boxwood Hall, even though he never set foot in the Buckeye State.

As Katherine Craig points out on her tour, Dayton got into hot water later in life for his association with the notorious Aaron Burr—who was also educated down the street at Elizabethtown Academy and who killed Hamilton in a duel in Weehawken. Small world, although for Hamilton apparently not big enough.

Changing with the Times

As Elizabeth grew up around Boxwood Hall, its purpose changed. After changing hands several times in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the building became the Elizabeth Home for Aged Women. It was not a final landing place for the destitute or infirm. As Tony Soprano insisted to his mother It’s not a nursing home, it’s a retirement community! so too was Boxwood Hall. It was a place for older women of sound mind and body, who for whatever reason, couldn’t afford their own housing. The women residing there participated in a variety of social functions and produced crafts such as needlepoint and crochet that could be sold to support the home.

In 1941, the state took over operation of Boxwood Hall. Over the next few decades, generous private donations of furniture and accessories from local residents slowly filled the building. When Craig began her duties at Boxwood Hall, the antiques were jumbled throughout the various rooms, without much rhyme or reason. But Craig instantly saw the potential.

“When I first got there, it looked too much like a furniture store,” she recalls. “It was like the world’s biggest dollhouse. I thought each room should represent one of the different periods of its history.”

So now it does. The curated period décor, in fact, helps Craig set the scene as she moves from room to room, guiding visitors through the evolution of the historic home. On her tours, she talks about the other iterations of the mansion, including stints as a school for girls and as home to the Red Cross.

Craig also talks about the architectural history of Boxwood Hall and changes in the surrounding neighborhood. At the conclusion of her tours, you feel as if you’ve walked in the footsteps of its many residents. Which, Craig maintains, is the best takeaway: “Whether it is someone famous, infamous or almost forgotten, when we look back, we are talking about human beings, not cardboard cut-outs.”

Editor’s Note: That Boxwood Hall is standing at all is a testament to the people of Elizabeth. Long before Craig arrived, the structure fell into disrepair and was slated for demolition. A group of citizens raised the funds needed to buy and renovate the property, and then deeded it to the state so it could be run as a museum. Boxwood Hall is open to visitors Monday thru Friday from 9:00 to 5:00, with an hour break from noon to 1:00. The museum is closed on weekends because Katherine Craig has a life, too.

Paul Bennett Hirsch’s Cultural Commentary

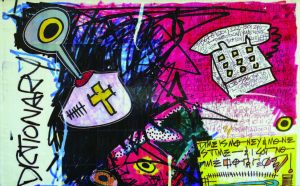

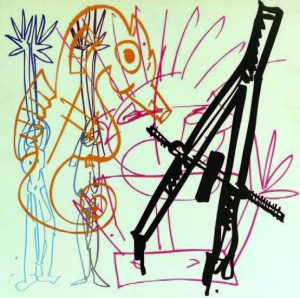

Pissarro, Monet, Cassatt and Degas are a few impressionist artists who rebelled against 19th-century academic art. In post-World War ll into the 1950s, Abstract Expressionism à la Pollock and de Kooning was sideswiped by Pop, or popular, art, with its mainstream images. Think, for example, Warhol’s soup cans, Lichtenstein’s comic-strip paintings, George Segal’s plaster-wrapped human figures. Thereafter, from the mid-1950s into the late ’70s and early ’80s, Pop art took hold. Think Keith Haring, and now Paul Bennett Hirsch, both of whom studied at The School of Visual Arts, NYC. Hirsch also holds a degree in fine arts and graphic design. Be of hyper vision when you see Hirsch’s works, bold and subtle, keenly observant, unique in language and energy, akin to the intricacy of the way a neurosurgeon navigates a brain.

Untitled (Scissor) (1989) 48” x 48” Acrylic Denim on Canvas Paul Bennett Hirsch #PBH

Untitled (Dictionary) • (1989) 74” x 45” Multipage laser enlargement, Paper, Acrylic, Canvas Paul Bennett Hirsch #PBH

Untitled (couple seahorse compass) (1991) 48” x 48” Acrylic on masonite Paul Bennett Hirsch #PBH

Factory Workers • (1992) 40” X 30” Ink, Uni Ball Metallic Paint on Board Paul Bennett Hirsch #PBH

Untitled (House Car Saw Phone) • (1991) 44” x 22 1/2” Lithograph printed 5 colors, Somerset textured white 300g. in an edition of 22, Rutgers University Press Center for Innovative Print Making. Paul Bennett Hirsch #PBH

Untitled (2000 Bomb Roche Pre 9-11 / Diary Premonition) (1990) 7’x5′ Multipage Laser Enlargement, Paper, Acrylic, Canvas Paul Bennett Hirsch #PBH

Untitled (There’s A Sister At The Supper) (1992) 48” x 48” Acrylic Krylon on Canvas Paul Bennett Hirsch #PBH

Untitled (Fertilization) • (1989) 70 x 50” mixed media painting on canvas Paul Bennett Hirsch #PBH

Self-Portrait

A long time New Jersey resident who now lives across the country in Washington, Pop artist Paul Bennett Hirsch knows that any and all styles of art can co-exist. Hirsch has created a huge, impressive body of work. “I began as a photo realist,” he says, “then I morphed into a neo-expressionist. Now I’ve embraced the moniker of creative survivalist.” His art includes works on canvas and paper, objects, plates, screens, steel sculptures, cones (of knowledge), clothing and textiles, flora and fauna, plastic proto paintings, and many more mediums…one might say “Picasso-esque,” for his art appears on just about anything but a fish skeleton. In addition to Hirsch’s museum exhibitions and corporate collections, he is working on a 2023 solo exhibition at the prestigious Ryan James Fine Arts gallery in Kirkland, WA. Search every inch of his work for the many-splendored symbols, letters, words and numbers within his dominant images at ryanjamesfinearts.com or check out his Facebook page (paul.b.hirsch).

—Tova Navarra

www.istockphoto.com

A Nobel-winning breakthrough and lessons from the pandemic

have cancer researchers rushing to develop and test new vaccines.

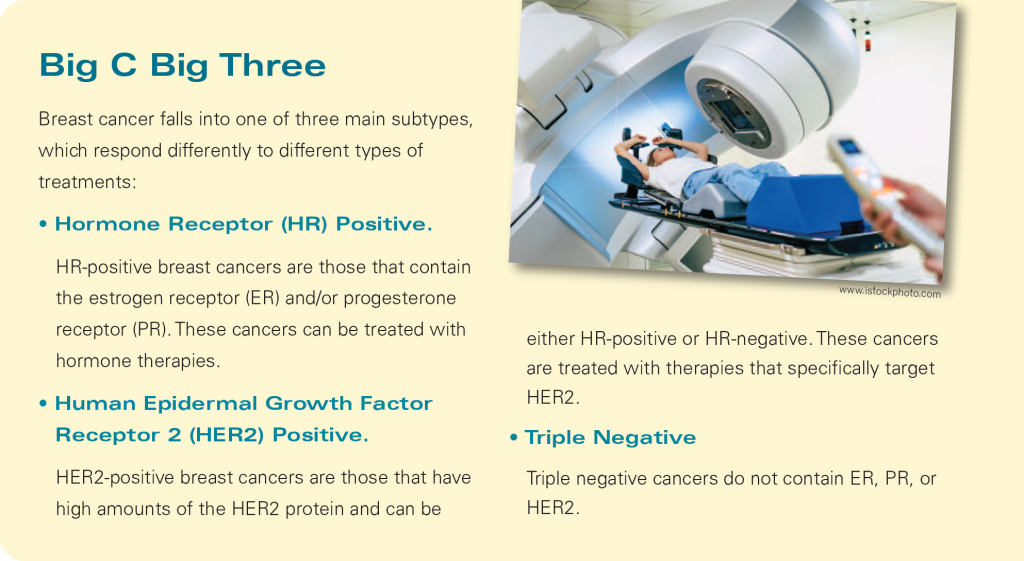

Understanding how and why the human body works, and when and why it doesn’t, has led to countless health and wellness breakthroughs—including innovative treat-ments, therapies, medications and vaccines. Breast Cancer Awareness Month, which concluded in October, focused our attention on the impact of the disease, as well as the importance of access to screenings. Another component of Breast Cancer Awareness Month is fundraising earmarked for research. In recent years, more and more of that research has concentrated in an area with which we have all become intimately familiar these past few years: vaccines.

The search for clues on how the immune system might be enlisted in the battle against cancer has intensified thanks in part to: 1) COVID having taught us how to dramatically accelerate the production of new vaccines, and 2) a Nobel Prize-winning discovery that clears the path for new cancer vaccines to be tested. Much of this research has been devoted to understanding cancer itself, particularly the ways in which a tumor’s defenses are able to thwart the immune system. Researchers are not only getting a firmer grasp on how this happens but, just as importantly, how well the human body already eliminates rogue cells as they develop. There is even a word for it: immunosurveillance.

“This is a very exciting time to be an oncologist,” says Clarissa Henson, MD, Chairman of Radiation Oncology at Trinitas Comprehensive Cancer Center (left). “The fields of virology, immunology and oncology have been rapidly joining forces to combat and cure cancer.”

Trinitas patients now have access to a wide range of advanced treatment options such as immunotherapy, precision medicine, and clinical trials—many of which are not available elsewhere—thanks to RWJBarnabas Health’s partnership with Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, the state’s only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Researchers there are focused on translating discoveries directly to patients to reduce the incidence of cancer and improve outcomes.

MUC1

Many of those researchers believe that tumors are formed by cells that have found a way to escape immunosurveillance by “looking” normal—sort of a microscopic cat-and-mouse game going on inside our bodies all the time. If this is indeed the case, then the key to effective cancer vaccines may be learning how both the cat and the mouse do what they do. This information would be used to “teach” the immune system how to recognize the cells that elude it now so that they can be neutralized.

One exciting recent breakthrough, by a team at the University of Pittsburgh, was the identification of an antigen specific to tumors—in other words, a molecule or protein that exists on cancer cells but not on normal ones. Researchers believe this is a critical first step in teaching the immune system what to target. Among the cancers that have this antigen, which is called MUC1, is breast cancer. MUC1is also present on cells related to colon, lung, pancreatic and prostate cancer. That’s quite a list of targets, which explains the excitement in the vaccine community. Initial trials have been focused on preventing pre-malignant lesions, such as polyps, from becoming malignant. A similar trial at Pittsburgh on early breast cancer is already gearing up.

Another branch of cancer vaccine research that holds great promise is the field of neoantigen vaccines. These vaccines address mutations unique to one person’s tumor—a “personalized” vaccine, one might say. A neoantigen vaccine is created using a sample of an individual’s tumor, and is then used to prime that person’s immune system to attack the cancer cells. Trials on melanoma patients have shown great promise, prompting research on a neoantigen vaccine targeting pancreatic cancer. An exciting aspect of these types of vaccines is that, once effective versions have been developed, they could be produced very rapidly thanks to the work that was done to scale up production of coronavirus vaccines.

Although it is encouraging to think that we all might have personalized vaccines one day, that may not be necessary because, as mentioned earlier, many different cancers share similar antigens. A case in point is HER2-positive breast cancer, which accounts for about a quarter of all breast cancers and frequently relapses and metastasizes. The HER2 molecule is considered a driver antigen, meaning that it instructs cells to keep dividing. Without these instructions, the cancer cannot grow. A vaccine that prompts the immune system to make its own HER2 antibodies would be a game-changer.

www.istockphoto.com

An early version of that game-changer has already been through initial trials at the Mayo Clinic. A HER2 vaccine was given to 22 patients with invasive breast cancer. Two-plus years later, 20 of the 22 showed no sign of recurrences. It is a small sample, but the results are encouraging. The same team is also working on a vaccine that might prevent breast cancer in women at high risk for the disease.

“We are still learning more every day about the human body and how the immune system fights illness, viruses and cancer,” says Dr. Henson, who adds that the pandemic provided an impetus for some important research, including a study at Emory University.

“Radiation is used to kill both viruses and cancer, UV light is used for sterilization and to kill bacteria and viruses, while higher-energy x-rays are used to kill cancer,” she explains. “During the pandemic, the Emory study showed that low-dose radiation to the lungs in patients with COVID-19 related pneumonia resulted in quicker recovery times, lower rates of intubation and quicker time to hospital discharge.”

Checkpoint Inhibitors

If we are indeed, as top researchers are optimistic, approaching an age of breast cancer breakthroughs, it is due in no small part to an earlier breakthrough that has made research in therapeutic cancer vaccines possible. That would be the development of checkpoint inhibitors, which are now combined with the vaccines given to patients in many test trials.

Chemotherapy suppresses the body’s response to an immunologic stimulus. So, too, does cancer itself. Because cancer vaccines are tested on people with cancer, it can be challenging to accurately gauge the effectiveness of the vaccines. Checkpoint inhibitors stimulate immune checkpoints, counteracting the effects of cancer. This has cleared the path for critical research. In 2018, the Nobel Prize was awarded to James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo for “their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation.”

Checkpoint inhibitors technically fall under the heading of immunotherapy. Immunotherapy is another area of intense focus that has yielded possible breakthroughs in the fight against breast cancer. An article earlier this year in JAMA Oncology reported work by Korean researchers on a new treatment for HER2-postive breast cancer that works as well as current drugs, but without the often-devastating side effects. Many HER2 patients receive TCHP chemotherapy before surgery with fairly good results; about half go into remission. But TCHP is highly toxic, especially to gastric mucosal cells, which can result in severe diarrhea and even sepsis. It is hard on bone marrow, too. So TCHP is not recommended on elderly patients or women with certain comorbidities.

The Korean phase-2 study replaced carboplatin—the “C” in TCHP—with a monoclonal antibody called atezolizumab and enrolled 67 HER2-positive patients in a yearlong trial. After surgery, patients received more targeted immunotherapy and, at the end of the trials, 61% responded completely. There were still side effects (including immune-related events in 6% of trial participants), but mostly they were aches and pains and some skin conditions.

In other words, another encouraging step in the development of new weapons in the breast cancer arsenal.

An old-school moniker revisited.

In the world of sports, athletes often use “Pop” as a good-natured term of derision for opponents and teammates whose hair has turned white (or disappeared altogether)—or whose skills have eroded with age. For a select few, however, the nickname has been one of affection, reverence and respect. Here’s a look at our Top 10 Pops…

Office of the President

Gregg Popovich (1949– )

Known as “Coach Pop” long before a gray hair appeared on his head, Popovich led the San Antonio spurs to winning seasons in each of his first 22 years as their coach. He has won more games than any coach in pro basketball history and collected five championship rings.

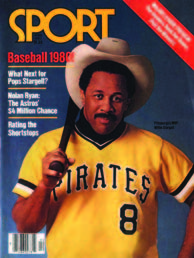

Macfadden Publications

Willie Stargell (1940–2001)

The Pittsburgh Pirates’ Hall of Fame power hitter acquired his nickname after becoming the team’s elder statesman in the twilight years of his career. In 1979, his 18th season, he made headlines by winning the National League MVP award and leading the club to a World Series championship.

Basketball Hall of Fame

William Gates (1917–1999)

Seven months before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in major league baseball, Pop Gates debuted for the team that now plays as the Atlanta Hawks, in the National Basketball League—forerunner of the NBA. Eight years earlier, he’d led the Harlem Rens (short for Renaissance) to the World Championship of professional basketball.

Arizona Alumni Association

James McKale (1887–1967)

Pop McKale became an institution at the University of Arizona, serving as athletic director from 1914 to 1957. He was responsible for the naming of the school’s sports teams—the Wildcats—and the football stadium was named in his honor.

Oklahoma Athletics

Lee Ivy (1916–2003)

Only a handful of head coaches led teams in both the American Football League and the National Football League, and Ivy was one of them. Players were already calling him “Pop” when he played for the Cardinals in the 1940s because he was prematurely bald.

Upper Case Editorial

John Henry Lloyd (1884–1964)

One of the two or three greatest shortstops in baseball history, Lloyd played his entire career in the Negro Leagues. He lived the last half of his life in New Jersey, becoming a beloved community hero in Atlantic City.

Wiley College

Fred Long (1896–1966)

Pop Long was a legendary football coach for four historically black colleges, winning 227 games between 1921 and 1965. He led the Wiley (Texas) Wildcats to national titles in 1928, 1932 and 1945.

Upper Case Editorial

Glenn Warner (1871–1954)

During four-plus decades as a college football coach, Pop Warner coached four national champions and devised offensive sets and special plays, such as the screen pass, that led to the modern game. Among the legendary players he developed were Jim Thorpe and Ernie Nevers.

GAD Baseball

No Fly Zone

Bill Schriver (1865–1932)

In the early days of baseball, players were obsessed with the challenge of catching a ball tossed from the top of the Washington Monument, more than 500 feet above the National Mall. Pop Schriver was reportedly the first to try, in 1894, and nearly pulled it off. The ball—you guessed it—popped out of his mitt.

Upper Case Editorial

John Corkhill (1858–1921)

Pop Corkhil was a clutch-hitting outfielder who helped Brooklyn win pennants in 1889 and 1890. He retired at 33 after being hit in the head with a pitch. Corkhill lived out his final years as a resident of Pennsauken, New Jersey.

Charles Snyder (1854–1924)

In an era when baseball teams positioned their best athlete behind home plate, Pop Snyder was one of the game’s top catchers. He became a respected umpire after his playing days.

www.istockphoto.com

War stories from the trenches. And basements. And attics.

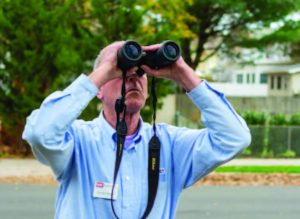

The scorching-hot New Jersey real estate market of the past few years has put a ton of pressure on the various people involved in taking a house from original listing to worry-free closing. It might be a stretch to say there have been “unsung heroes” in this process, but if there were, home inspectors would garner a lot of votes. They have one of those rare jobs where, the more detailed their work product is, the more likely it is that one person will be elated and another will be furious. Now that’s pressure.

Photo by Donald Rankin

As cringy as the process can be for the buyer, seller and real estate agents, the objective of a home inspection is undeniably admirable: to make sure the future homeowner is aware of the risks associated with a property in order to avoid any costly surprises. Tell that to the seller, who hopes the inspection report does not dramatically impact the final sale. And then there are the agents, whose livelihoods depend on steering clear of surprises and tamping down any kind of acrimony until all the documents have been signed.

Although not required in New Jersey, a home inspection is almost always recommended since, without one, the buyer inherits responsibility for all pre-sale conditions, no matter how major. Typically, the buyer pays the bill ($300 to $500 in most cases), so the home inspection company is working for them. Occasionally, a seller will order a “preemptive” inspection in order to gain a full understanding of a home’s pros and cons, which can then be listed in the seller’s disclosure that is filled out when a property is listed. Buyers rarely accept a seller’s inspection and usually arrange for an inspection on their own.

Photo by Mack Knight

Whoever is ordering the work, it does not—as any inspector will confirm—mean you are their boss. Donald Rankin, a Certified Home Inspector and Thermographer, counts among his most irritating clients “the buyer who treats me as stereotyped hired help,” as well as the occasional client who stalks him and impedes his progress and, of course, the client “who always knows better than me about everything.”

A typical inspection involves examining a home from top to bottom, starting in the basement and ending with the roof, with a “hit list” of targets in between (e.g., floors, walls, plumbing and electrical systems, the foundation and some optional extra-cost items such as radon testing and oil tank and septic system sweeps). If an inspector is unable to access something (behind a wall, for example) that is usually listed in the report. Should any local building code violations be observed, these too usually merit honorable mention in the final inspection report.

With a record number of first-time homebuyers entering the market in New Jersey over the last couple of years, the job of inspectors has taken on a bit more of an “educational” role. The untrained eye can miss significant flaws that might be obvious to buyers on their third or fourth home.

Jim Stoffers of Mack Knight Home Inspections says even a rookie home shopper can detect potentially serious problems if they know what to look for. For example, he recently inspected a brand-new build and saw a ridgeline issue, which hinted that something wasn’t quite right between the basement and the roof. In some lower-value homes, sometimes you can spot foundation issues before you even get close to the front door. “All houses settle,” he points out. “Some faster than others. However, a five-year-old house shouldn’t be as settled as a 100-year-old house.”

Stoffers adds that it is not unusual for buyers to read his inspection report and say, Wow, we’ve been in here twice and didn’t notice that! “And I completely understand,” he says. “They are looking for the beauty in a home they want, imagining what it will look like with their furniture and their family.”

What should first-time buyers take note of? Among the top-line consensus items are sloping floors, uneven gaps under interior doors, and horizontal cracks in unfinished basements. All could be signs of bigger issues.

Most home inspectors follow a Code of Ethics, such as the one developed by the American Society of Home Inspectors (ASHI), which emphasizes integrity, clarity, honesty and, above all, objectivity. As mentioned earlier, home inspectors function much like a dual agency in real estate transactions in that the resulting report is equally significant to both the determined seller and the prudent buyer in closing the sale. And they take this role very seriously. Often the commitment paperwork and contract of sale will include a home inspection contingency—which means a report that accurately identifies a major (unexpected) issue can allow a nervous buyer to wriggle off the hook or initiate an entirely new negotiation on price. Veteran home inspectors always prepare in advance how to handle delivering either good news or bad to their clients. The reactions of the parties involved can run the gamut of human emotions, from pleased to crazed. The good inspector has seen it all.

The great inspector can handle it all.

Photo by Rick Pettit

Rick Pettit of Eastern Home Inspections of New Jersey estimates he has done more than 14,000 inspections during a career that stretches back to the mid-1980s. He enjoys sitting down with his clients and reviewing his report. He keeps his terms simple and makes sure his clients understand what he’s talking about.

“I remind everyone that everything that is wrong can be fixed—at a price,” he says.

Pettit notes that the industry has changed recently, with more people getting into the home inspection business, and is disappointed that licensing requirements, in his view, have become so lax. There are too many new hires who are “overly confident and think they don’t need much training to get a license.” One thing that hasn’t changed is that he loves working with his prospective homeowners, even on those rare occasions where they might be tempted to tell him how to do his job. Like every inspector, though, Pettit has had a nightmare experience or two.

“I did have a buyer who kept asking so many questions that I couldn’t get my job done,” he recalls. “Then she ended up suing me…accusing me of not being thorough enough to answer her questions!”

www.istockphoto.com

After reviewing Pettit’s report, the judge dismissed the case. That didn’t stop the woman from confronting him in the parking lot screaming, “There’s no justice! No justice at all!”

Lynn Brancato joined her spouse, John, 17 years ago to form a husband-wife team that goes by JAB Inspections. In serving countless thousands of customers since then, they have learned to give a client the full benefit of their experience and expertise, but also to stop short of offering advice. You don’t want a dentist doing your heart surgery, she likes to joke. Being a woman in a male-dominated industry isn’t always fun and games, however. While many clients are thrilled about hiring a woman, she suspects that some callers hang up when they realize they are not dealing with a man. Brancato tries to be philosophical about it.

“I accept that many men don’t accept me working on the job in the same way that I have had to accept working in their world,” she says, adding that, “like women everywhere, female inspectors still have to take care of people, places and things while trying to do our job.”

Brancato prides herself in being able to “sniff out” potential problems that might easily be missed.

“I have the nose of a Labrador,” she smiles.

www.istockphoto.com

Brancato has seen her fair share of amateur renovations, but while looking at a new playroom in one particular house, her instincts told her something wasn’t quite right. After chatting up a neighbor, she discovered that in the 1960’s there had been an in-ground fiberglass pool in the same spot—and that it was never removed. The large “play” room was more of a “pool” room” without a proper foundation.

Brancato’s advice to other women in the field? Don’t be afraid to be who you are and know what you know.

Donald Rankin has no fear of being who he is. A native of Ireland and a gifted storyteller, he loves recounting the ups and downs from a seven-year career that has included around 2,500 home inspections. Home buying is a high-anxiety situation, he points out, and he relishes the challenge of meeting new people and making them smile. What makes Rankin anxious?

“Extreme summer heat just kills me,” he admits. “I warn ahead whenever it’s going to be a ‘two-towel’ day. I really don’t like filthy dirty crawl spaces. I got bitten by a poisonous spider once.”

www.istockphoto.com

With apologies to the Boy Scouts, Rankin’s motto is Be prepared…because there’s always going to be a challenge—from the buyer, the seller or even the house itself. Some things, he adds, you can never be totally prepared for. Like the time a client brought his entire family along on the inspection, including an uncle who took the liberty of disassembling the furnace and leaving Rankin to explain to the seller why it was in pieces on the basement floor.

Even so, Rankin maintains that “nothing can rattle me. I’ve seen it all.”

Among the many things our four house inspectors have in common is that they will always find issues. “That’s our job,” Jim Stoffers explains. “It comes down to what you want to negotiate. The rest is out of our control.”

They also agree that buying a house “As Is” can be a very risky proposition, and remind buyers who do that, just because you waive the inspection with the seller, it doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t bring in an inspector for your own purposes. In fact, many listings that begin “As Is” can be negotiated to carve out a limited inspection, including environmental, structural and safety issues only.

Another area of concurrence is that successful inspectors understand that objectivity, clarity, integrity and honesty is key. Lynn Brancato sums it up well when she says, “My job is to give the client what they need when we know and they don’t.”

New Jersey’s contributions to American popular culture are historically significant and meticu-lously documented, if not always fully appreciated in real time. Kevin Smith is practically the embodiment of real time. He is in the moment and of the moment, and that has defined his work as a film maker, podcaster and all-around multi-dimensional entertainment visionary. Clerks III, which debuted in September at an historic Jersey Shore movie theater he now owns, is the latest chapter in a three-decade career that has included critically acclaimed films, innovative live tours and podcast mega-success—punctuated by a near-fatal heart attack. The grassroots success of Smith’s first effort, Clerks, taught him valuable lessons about the movie business and the importance of forging a personal connection with his audience. Gerry Strauss asked Kevin to explore the roots of his fascination with film and examine how building connections —with actors, directors and fans—has enabled him to keep moving forward in dynamic, surprising and impactful ways.

EDGE: I admire the passion with which you stay connected with your New Jersey roots. Now that extends to the theater you’ve bought in Atlantic Highlands.

KS: It was one of my hometown theaters where I grew up. We’re coming up with this big mural to put into the lobby that’s got all the people from New Jersey who became successful. Look, there’s Tom Cruise, he was here once, and DeVito and Nicholson and Brittany Murphy. The idea of some kid coming into theater looking up and being like, These people came from New Jersey? Maybe I’ve got a shot—it takes me back to when I was a kid.

EDGE: How so?

Upper Case Editorial

KS: When anybody would reference New Jersey in a movie or TV show, it was like, They know we exist. You felt positively cosmopolitan. You felt like you were part of the conversation. It was thrilling. I think that’s what I’ve always been trying to accomplish, to be part of the conversation. And I found that Jersey is an excellent conversation-starter worldwide. It carries with it credibility that other places don’t necessarily have. If I was from Rhode Island, it wouldn’t make much of a difference.

EDGE: I was thinking about films from my youth with a New Jersey connection, like The Karate Kid, and then realized the first few minutes of that movie they were getting the heck out of New Jersey.

KS: Yes! [laughs] Most Jersey origin stories have people leaving the state. That was one thing I was always proud about. My characters were content to stay within state.

In Clerks II, the plot hinged on whether or not Dante’s going to move away to Florida, and then ultimately he decides to stay. So yeah, New Jersey is in my DNA, man. I absolutely adore the state. It adds this weird layer of working-class credibility—which I think Bruce and Bon Jovi are kind of responsible for—that I have been benefiting from, and it has been absolutely magical. Being from New Jersey has sometimes been the only thing that’s kept my career alive.

EDGE: How do you think storytelling became part of your DNA?

KS: My journey with self-expression, for lack of a better word, began because of a Jersey Girl—specifically, my sister Virginia. I found a composition notebook under her bed when I was about five or six years old. I opened it up and the front page was a drawing of her and her friends kneeling around a cellar door. The title was The Secret of the Cellar Door. “What is this?” I asked. She said, “This is a book that I’m writing. It’s a story about me and my friends on an adventure.” I was like, “You can’t just write a book. You’ve got to ask for permission from the government…we have a library card and Anybody can write whatever they want at any time.” That really captured my imagination. The family had this big electric typewriter, this thing you plugged in and it hummed and it sounded official, and it was very powerful. Once I learned how to use it and tell a story, that electric typewriter became one of my best friends. the flag is on it, and the eagle. It’s official.” She goes, “Look, not every book looks like the books in the library, and you don’t have to get ‘permission’ to write, ever.

EDGE: When did you become conscious of movie making?

Film Venture Intl

KS: There was a movie called Don’t Go into the House that was shot in our neck of the woods, in Atlantic Highlands—including in front of that movie theater that I’m buying. It was a horror movie and the house that represented the killer’s lair—where he would bring women and chain them up and then use a flame thrower on them—is now the Historical Society of Atlantic Highlands. When we were kids, you would watch that movie and you’d be like, that’s here. I could bike to that house. That’s real, that exists. Little tangible moments like that.

EDGE: Nothing locally in the way of influences or role models?

KS: No. The role model had to come from outside of the state: Richard Linklater. When I saw Slacker I was like, Wait, you could be in nowhere, Texas, and make a movie? I didn’t know it was Austin [laughs]. I didn’t realize Austin was the capital of Texas. But a little ignorance went a long way because, when I saw the movie, I was like, This guy making a movie in Texas means that I can make a movie in New Jersey. It was saying that you ain’t got to be from New York or Los Angeles—make it up in your world. He made Austin the backdrop of the city, almost the main character. I was like, where I live is interesting and I’ve got that whole convenience store. So he inspired me more than anybody.

EDGE: Do you take pride in the fact that you’re now serving that role, inspiring up-and-comers?

KS: I love that. Money was never the big driver for me. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not a communist, I’m a capitalist as much as the next guy, but it has never really been the motivator. The motivator at first was for people to hear my voice, my stories, my opinions. Now the driver is the people that you inspire along the way. Richard Linklater did it for me. He wasn’t looking for me. He wasn’t thinking about me. But his art made me believe that maybe I could do something. The same with Spike Lee. I recently saw Spike Lee in Minneapolis at VeeCon, the big NFT convention. We share mutual friends. I told him, “When you started your journey, when you made She’s Gotta Have It, and even before that when you went to NYU, I know you weren’t trying to reach me. But you did and I can’t thank you enough, it launched my ship.”

EDGE: How did he respond?

Miramax

KS: He said, “The professor teaches all students, Kevin. So if I reached you, then that was the point. Then I did my job.” Later he said, “We’re still here. We’re still doing it.” That “we” meant the world to me. That made me feel like such a professional. Seeing Spike take off with She’s Gotta Have It, that was fuel for me later on. It’s no coincidence that She’s Gotta Have It was a black-and-white movie and so was Clerks.

EDGE: It strikes me that the Clerks franchise is the thing you go back to when you’ve got something to say from the heart. Are these movies most personal work among all of the films you’ve done?

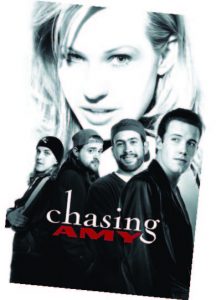

KS: I would say of everything I’ve done, the Clerks movies always strike closest to home. Chasing Amy runs second. There’s personal stuff in all the movies, but Clerks started me on this path.

EDGE: You told that story in the first movie so naturally.

KS: It was easy to tell the story because I was in that world. I worked at that convenience store. I was a guy who tended register, man, at a bunch of different convenience stores. So I knew retail and I knew what it was like to deal with customers. When we made Clerks II, twelve years after the first one, at that point I had a full-blown movie career. I didn’t know about retail anymore, so it had to be infused with something else altogether, because it lacked that personal edge of knowing what it’s like to be an employee. The boys had to go on a journey that was kind of similar to mine, where, by the end of the movie they realized, Oh my god…we can be our own bosses instead of just working for somebody else. But Clerks III is super personal because not only does Randal have my heart attack, but then the boys go on and make my movie. They get to make their version of Clerks. That’s been the formula for Clerks since the beginning: take my personal life and fictionalize it to some degree. Clerks III was like midlife crisis fantasy camp. I got to go back to the job that I have a very complex relationship with. When I worked at Quick Stop, I didn’t want to work at Quick Stop. I wanted to be any place else—until 10:30, when we locked the doors and I would hang out inside Quick Stop ’til three, four in the morning with my friends. It was a clubhouse. I loved the place…I just didn’t like working. So I got to go back to Quick Stop all summer when we were shooting the movie, but in the best way possible. I would literally walk in and out of the store and walk in RST Video like I used to in the late ’80s and early ’90s. But I didn’t have to wait on customers and I didn’t have to be there. I was there by choice. And when we were done making pretend that we were working, we all left, walked away. I didn’t have to mop the floors like I used to back in the day. It was the best possible version of working at Quick Stop.

EDGE: You’ve worked with a number of different actors who were just arriving in the film world—Ben Affleck and Jason Lee come to mind—whom you helped shepherd into becoming the stars they became. Do you look back at those times with pride, knowing that you were able to be a part of that development?

Smodcast Pictures