News, views and insights on maintaining a healthy edge.

Movers & (Salt) Shakers

Movers & (Salt) Shakers

Remember the row over Michael Bloomberg’s ban on super-sized sodas? Well, the Big Apple is now taking aim on sodium. New York’s Department of Health proposed that chain restaurants operating in the five boroughs add a salt-shaker icon to menu items that contain more than the recommended daily limit of 2,300 milligrams (roughly a teaspoon). “Studies show that those of us who consume higher amounts of sodium are more likely to develop hypertension, and those who already have high blood pressure are likely to develop heart problems and stroke as a result of higher sodium intake,” says

Michelle Ali, RD

Director, Food and Nutrition, Trinitas Regional Medical Center 908.994.5396

Michelle Ali, RD, Director of Food and Nutrition at Trinitas. You may not want to hear this (or you may know it already and don’t care) but every major chain has at least one delicious-sounding entrée that pushes past 3,000 mg of salt. And they aren’t always the obvious ones. Ali points out that, while most fruits and vegetables are naturally low in sodium, when they are prepared, sodium/salt is sometimes added to improve flavor. “Nutrition information is a tool that can guide consumers to make better food choices,” she says. “If a dish exceeds the recommended amount of sodium, move on to another food choice with less. Do portion control; take a portion home. Finally, add a salad, limit the dressing, and finish off with fresh fruit for dessert.” A final vote on the sodium “warning” should occur this September and the little shakers may be popping up on menus in time for the holiday season.

Bum Deal for New Yorkers

Bum Deal for New Yorkers

What are those folks across the river up to these days? Not much, according to a study by NYU’s School of Medicine. According to findings published in the latest issue of Preventing Chronic Disease, the average New Yorker sits more than seven hours a day. The study involved 3,600 subjects who wore devices that monitored whether they were moving or sedentary during waking hours. The seven hours broke down to four during the day and three in the evening. Manhattanites actually logged eight hours on their fannies. The stats for men and women were equal. Trinitas Endovascular Surgeon

Ajay Dhadwal, MD RPVI

Endovascular Surgeon, Trinitas Regional Medical Center (Assistant Professor, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School) 973.972.9371

Ajay Dhadwal, MD RPVI, observes that the ill effects of a sedentary lifestyle influence almost every aspect of one’s health, from vascular disease in the blood vessels supplying the brain and the legs, to joint pains and obesity, to heart disease. “Endovascular surgeons often see conditions which, at their worst, can lead to stroke and eventual amputation of the legs,” he says. “Even a minimal increase in activity level can help reduce future risk, especially for those who smoke. For certain patients, regular walking can be as beneficial in the long term as stenting blood vessels of the leg in improving the distance they can walk. To see an overall positive impact, take the stairs more often or walk 20 minutes a day.”

$150 Up in Smoke

$150 Up in Smoke

The Holy Grail for anti-tobacco groups is an idiot-proof way to stop smoking. Patches, gums and hypnotherapy are effective in some cases but not in others. A recent study of 2,500 smokers took a different approach and yielded some breathtaking results. The key ingredient was bribery. Subjects were divided into four groups and offered different types of financial incentives. Two groups were offered financial rewards for quitting. Two had to put their own cash on the line. Smokers who had to make a $150 deposit and stop smoking to get it back had a success rate twice as high as the first two groups. More revealing is that the $150 group had a success rate five times that of smokers who undergo traditional cessation programs.

Nothing Rotten in the State of Denmark

Nothing Rotten in the State of Denmark

Allergy awareness in grade schools has been growing for a good two decades now. In some schools, the presence of a single peanut is enough to trigger a lockdown. But do school lunches actually have the potential to positively impact childhood allergies? A study published in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition this summer attempted to answer this question. Nine Danish schools gave 3rd and 4th Graders their typical pre-packed lunches for three months, and then meals rich in fish, vegetables and fiber for another three months. At the end of each period, parents were asked to evaluate the status of their children’s asthma and/or allergies. The difference? None. Although undoubtedly healthier, the nutritionally balanced school lunches did not “perform” any better than the usual items the kids were eating when it came to allergies. Research on childhood allergies is critical, says

Kevin Lukenda, DO

Chairman, Family Medicine Department

908.925.9309

Dr. Lukenda, DO, Chairman of the Trinitas Family Medicine Department, even when the results are not headline-grabbing. “A child who experiences a full blown anaphylactic response to a food allergen can experience lifelong effects and anxieties,” he says. “This research doesn’t change the fact that having a peanut-free table or classroom can have a tremendous upside benefit for the student and their family, as it allows them to focus on school and not worry about a potentially life-threatening situation.”

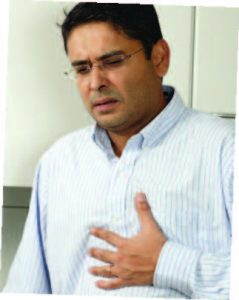

Link Between Heartburn & Heart Attacks

Link Between Heartburn & Heart Attacks

Back in June, acid reflux drugs were in the news after a study conducted by researchers at Stanford University and Houston Methodist Hospital showed a link between their use and an increased risk of heart attacks. The drugs in question are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which are among the most widely used and prescribed in the United States and are marketed under names such as Prilosec, Prevacid and Nexium. The researchers scanned the medical records of 2.9 million patients for key words like “heart attack” and found that they occurred at a rate 15 to 20 percent higher with people who used PPIs. The same correlation did not exist with patients who treated their acid reflux with H2 blockers, including Tagamet and Zantac. It’s worth noting that this is a highly unconventional approach to big data, and although the media grabbed it and ran, the medical community looks at the methodology with natural skepticism. This type of conclusion is typically the result of a randomized control trial, where PPIs would be compared to a placebo to see if the drug did actually produce the specific effect. On the other hand, the fact that H2 blockers did not show a heart attack link supports the idea that more research on PPIs is probably warranted. Until that happens, patients taking PPIs—whether prescribed or over the counter—should talk to their doctors before their next trip to the pharmacy.

CBT Helping Insomniacs Hit the Snooze Button

CBT Helping Insomniacs Hit the Snooze Button

Recent findings published in Annals of Internal Medicine show that people with severe sleep issues can benefit from Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT). This conclusion was the result of an evidence review of 20 separate studies, and showed that insomniacs (individuals who have trouble sleeping for at least a month) who underwent CBT fell asleep 20 minutes faster and reduced the time they were awake once they fell asleep by a half hour. The data was generated by comparisons between groups that took sleeping pills and groups that underwent short sessions with therapists. The CBT group learned new strategies for falling asleep and staying asleep. A major component of CBT is stimulus control, which involves meditative exercises and relaxation techniques.

One interesting item that emerged is that getting out of bed and “hitting the reset button” is better than endless tossing and turning.

Anwar Y. Ghali, MD, MPA Chairman, Psychiatry 908.994.7454

Dr. Anwar Y. Ghali, MD, MPA, Chairman of Psychiatry at Trinitas, agrees that this strategy can help. “Patients who wake up in the middle of the night should not stay awake in bed for longer than about 30 minutes,” he says. “They should avoid keeping an eye on a watch or a clock, since that may interfere with the ability to go back to sleep. Leave the bed and engage in other activities until you feel sleepy again, then go back to bed. Don’t go to the refrigerator for a midnight snack. You may end up perpetuating the habit of getting up in the middle of the night for that trip to the refrigerator.”

Vipin Garg, MD

Director, Trinitas Comprehensive Sleep Disorders Center 908.994.8880

Dr. Vipin Garg, MD, Medical Director of the Trinitas Comprehensive Sleep Disorders Center, agrees that getting to sleep and staying asleep can become a matter of habit. “Many times, specialists in sleep medicine like me recommend sleep restriction technique for insomnia,” he says. “Patients are advised to get into the habit of a certain number of hours of sleep and maintain a certain bedtime and wake-up time. Once they are in this pattern, patients are advised to refrain from going to bed earlier than their normal time, even if they feel sleepy. Often, those who suffer from insomnia are shocked to hear this, since the common belief is that the more time you spend in bed, the more sleep you get. Sleep restriction therapy consolidates fragmented sleep to continuous and deeper sleep.”

For less severe cases of insomnia, there are a number of websites that can help (including calm.com), and the occasional intake of Rozerem or Silenor. However, given that insomnia has been linked to a wide range of health issues—including weight gain, depression, anxiety, heart disease and diabetes—and that sleeping pills aren’t a good long-term solution, chances are you’ll be hearing more and more about CBT and other sleep-related therapies.

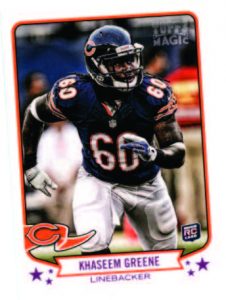

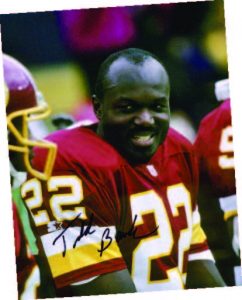

An NFL linebacker comes home.

On a sunny Saturday in Elizabeth, wide-eyed young football players fill Waterfront Field in the never-ending quest to burnish their skills. It might sound like a typical late-spring weekend morning here, but there is one big difference. On this day, the kids are being coached by a professional: hometown hero Khaseem Greene, twice Big East Defensive Player of the Year at Rutgers and now a linebacker for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers of the NFL.

For most of these kids, it is their first experience interacting with a player of Greene’s caliber. Towering over his charges, he is someone they can look up to, literally and figuratively. No matter where his football travels have taken him, Greene has always come back home. This is the second year he has hosted his football camp. It’s not a money-maker (many NFL player camps are), nor is it just about teaching on-field techniques to the city’s kids. Greene sees his camps as an important way of making a meaningful difference in the town where he first caught the eye of college recruiters as a defensive back of the state-champion Elizabeth High School varsity.

Topps, Inc.

“Kids might read about me and know a little bit about me,” Greene says, “but my coming back and having free camps—getting the kids involved with football and teaching them the basics—is for me a joy, because they get to know me as a person. We get to meet and interact.”

Greene understands what the kids of the city are going through today. He lets them know that they should not hesitate to “dream big,” because you never know the opportunities that are out in front of you. In Greene’s case, his quickness and ferocious tackling prompted a move to linebacker his junior year at Rutgers. That decision changed his life. He instantly became one of the best at the position in the country and earned Big East Defensive Player of the Year Awards in 2011 and 2012. He was selected in the fourth round of the 2013 NFL draft by the Chicago Bears and has been working hard to establish himself in the pros the last couple of seasons.

The kids at Waterfront Park don’t hear a lot of local success stories like Greene’s. Which is why he feels compelled to tell it. He hopes others from Elizabeth who find success follow his lead and come back to share their stories. “It’s a way to motivate a kid to want to do better, to make it somewhere in life for themselves,” he says. “It’s special that I get to be the guy that comes back and actually does camps and gets involved in the community the way I do. It’s definitely a big deal for me. I can’t even put it into words how excited I would’ve been to have been able to attend a camp like this when I was a kid.”

The kids at Waterfront Park don’t hear a lot of local success stories like Greene’s. Which is why he feels compelled to tell it. He hopes others from Elizabeth who find success follow his lead and come back to share their stories. “It’s a way to motivate a kid to want to do better, to make it somewhere in life for themselves,” he says. “It’s special that I get to be the guy that comes back and actually does camps and gets involved in the community the way I do. It’s definitely a big deal for me. I can’t even put it into words how excited I would’ve been to have been able to attend a camp like this when I was a kid.”

Greene found football as most young players in Elizabeth do, through his family. Several of his siblings, cousins, uncles—and especially his father—were first-rate athletes. His dad played college football at Purdue. But it was Greene’s mother who kept him laser-focused on sports. “I credit my mom for keeping me involved in and making me love the game the way I do.”

Greene found football as most young players in Elizabeth do, through his family. Several of his siblings, cousins, uncles—and especially his father—were first-rate athletes. His dad played college football at Purdue. But it was Greene’s mother who kept him laser-focused on sports. “I credit my mom for keeping me involved in and making me love the game the way I do.”

Not surprisingly, it’s all hands on deck for the Greene family when it comes to making the camp happen—from tutoring the players to serving food to passing out camp t-shirts. “Family is the reason why I grind, the reason I do what I do,” he smiles. “It means everything to me for them to be there.”

Editor’s Note: Andrew Feldman first crossed paths with Khaseem Greene on the Rutgers campus, where Andrew earned a degree in Sports Management. He has profiled other pro athletes from the Garden State for njsportsheroes.com, including Muhammad Wilkerson and Elaine Zayak, and authored histories of Rutgers basketball and Seton Hall baseball for the web site.

Has the Gaming Revolution created a generation of e-casualties?

I’ve been in the city for the day and return to discover my son still home. “Did the SPCA end early?” I ask. He gives me a dazed look. “I’m leaving now.” It’s 4:30 in the afternoon and he’s been so absorbed in his video game that he lost track of time and reality. His volunteer job is nearly over for the day.

I am the mother of an electronic addict. By electronic, I don’t just mean compulsive video gaming, which is much like gambling addiction. I mean our son is addicted to the whole electronic shebang: TV, his computer, iTouch, iPhone, anyone else’s Xbox or Wii. He can play video games, Skype with fellow gamers, watch YouTube, Dr. Who and NCIS, simultaneously and ad infinitum. Electronics—like the Zombie movies he’s captivated by—suck in his brain, consuming his concentration at the expense of schoolwork and relationships. Neuroscientists have noticed the changes in electronic-obsessed brains that mimic those of an addict. And electronics for my son are like the junk food of his life.

www.istockphoto.com

If he could regulate his appetite and intake of electronics and limit his usage, I’d have no problem. But once he sinks into the family room sofa, he becomes an electronic couch potato. I know these are strong words from a parent, and maybe it seems that I’m throwing our son under the bus.

However, he is cognizant of the issue and actually helped me research this story. We’ve been talking about his electronic addiction for several years and at college he has a “coach” with whom he can discuss his obsession with gaming.

“Vidiot” perhaps is too harsh a moniker for my son, as he eloquently discusses the finer points of a particular game’s digital animation and interaction. Gamers see video games as a cross between a science and an art. This is nothing new. We can trace these gamers back historically to arcade game aficionados of 30 and 40 years ago. It’s become so imbedded in our culture that various science museums have mounted interactive gaming retrospectives, beginning with Pong and Space Invaders. There is, in fact, an appreciation among video gamers that borders on connoisseurship (in the way a wine expert might also be a drunkard). Our son’s good friend, who plays in video game tournaments for minor profit, suggested I try a certain game and see how fast I got hooked. Interesting idea, but it holds no appeal to me.

To be sure, electronics has influenced our culture in positive ways. Both the art of Japanese anime and video graphics has fostered and influenced a whole new dimension and medium of art. Over 30 years ago, Nam June Paik fused video with music and performance art at his 1982 Whitney Museum retrospective. Digital art has flourished ever since. The audience created by global web use also has inspired some artists to create installations reflecting our obsessive usage. Artist Rachel Lee Hovnanian uses iPads as substitutes for husband and wife at the dinner table, bride and groom at their wedding feast and even her depiction of multi-generations of a Chinese family—all of whom are engrossed with their iPhones and ignoring each other—at a lunar New Year’s feast. Each installation depicts the haunting message of our daily struggle and infatuation with the cold allure of electronics and our subsequent loss of human interaction and warmth. And electronic addiction has become a hot topic in the press, with Jane Brody writing a two-part piece in the Science section of the New York Times and PBS recently airing a program devoted to Web Junkies.

Some colleges are viewing high-achieving gamers with good GPAs as possible recruits for campus e-sports. At Robert Morris University in Chicago, being a web jockey can translate into a full-ride scholarship. This fall, the University of Pikeville, a liberal arts college in Kentucky, has devoted 20 scholarships to League of Legends video gamers. League of Legends is a multiplayer battle game played online. Full Sail University in Winter Park, Florida, has offered BAs and MAs in game design and development for years. In addition, opportunities for gamers who can program abound in tech and entertainment companies. But that requires being entrepreneurial, ready to tackle Java and C++—and a willing ability to apply for a job.

E-Tox Detox

So electronics can be the user’s best friend or worst enemy. How did our son get hooked? We made every effort to discourage him. During the week, we’d snap the breaker that powered the TV to the Off position. We never owned an Xbox or PlayStation. Yet our son would ferret out video games online—passwords were minor hurdles—or play at friends’ houses. I can’t say it started with the Game Boy Color his grandmother gave him for Christmas, or the robotics team he joined in middle school. Probably part of the appeal of electronics is that it’s the playmate that’s always ready to play. Also, kids who have trouble focusing in school hyper-focus on gaming, and any anxiety in school will fuel the need to take solace in the alternate reality of video games. As our son matures, he is slowly grasping the benefits of focusing on his college courses and the rewards of working hard at his summer job.

Electronic addiction, it turns out, is not uniquely American. It is a global problem. India and Singapore actually have the highest incidence of Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD).

SETTING LIMITS

SETTING LIMITS

According to Dr. Rodger Goddard, Chief Psychologist at Trinitas, Internet use, social media, video gaming and being hooked on technology is a very intense problem for our children (and many adults) today.

Rodger Goddard, PhD Chief Psychologist,

Trinitas Regional Medical Center 908.994.7334

“I believe that we are undergoing an experiment in child-rearing. Never before in history have children been brought up with such intense exposure to technology. We do not yet know the results of this experiment. Research is showing that it may be having a very negative impact on our children’s learning skills and potential for success. The best advice for parents is to limit the time their child spends online and screening. Taking away electronics as a punishment can sometimes make using it even more attractive and exciting. Limiting its use gets a child more accustomed to being without continual technological exposure. Some parents have found that no screening outside of school work during the week and just a few hours on the weekend is just the right amount.”

According to a story in The Telegraph, a British newspaper, it’s epidemic in China, too: over 24 million suffer from some form of internet addiction. As a result, internet “boot camps” have been set up across China to take addicted kids—estimated at 14% of all youth—off the grid. In Japan, “internet fasting” has been set up to help create electronic “detox.”

Our own “detox” program has been to send our son on programs in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, where he is completely off-the-grid for weeks and able to experience nature’s beauty while ice-climbing, sea kayaking and scaling a rugged mountain at midnight to watch a meteor shower. As a college student, he has also trekked in faraway lands in the Himalayan foothills and in rural Central America. His most recent trip lasted a semester. While he has risen to the occasion, learned about Tibetan refugees and Buddhist monks and considered social justice issues of Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador, the challenge is still there. He returns to electronics the moment he gets home. And, needless to say, our version of detox has come with a hefty price tag.

Which is not to say that breaking video game addiction is ever cheap. Or easy. Although it is strikingly similar to more familiar addictions, such as alcohol, food and drugs, it is unlike them in that gaming can occupy every waking hour and involve everyone in an addict’s social network. Another problematic aspect of video game addiction is that gamers are separated from others by thousands of miles, and also by the ability to edit their words before hitting the return button. As a result, they can be uncomfortable dealing with others face-to-face and unedited, which makes traditional therapy a particular challenge.

The consensus among therapists is that families need to unplug their addicted gamers and, ideally, put them in situations where they are stimulated by non-electronic activities and develop off-line social skills. Options range from the aforementioned boot camps and fasting programs to wilderness camps and boarding schools, all of which are geared toward breaking the addiction. The challenge for parents is to pick an option that suits their child’s personality and demeanor.

www.istockphoto.com

Perhaps the most striking development in this area is that health insurance companies are starting to address video game addiction, if not specifically then under “compulsive disorders” or “depression.” Which means we may soon see an entire industry created around breaking this addiction.

MIT engineers recently developed a keyboard that delivers an electric jolt to over-users. I’m not sure our family will be an early adopter of this device, but I have to admit that it did cross my mind. EDGE

Editor’s Note: Is your child hooked on electronics? The web site netaddiction.com offers an internet addiction test that may be an eye-opener. Special thanks to Ben Fleming for his work on this story.

Lessons in the journey to educate our gifted and learning disabled son.

I never heard a three-year old talk like that. He sounds like a little professor. My husband and I would look at each other and smile proudly when our friends and family made remarks like these, as if we should be credited for our son’s charm and unusual precociousness. His grown-up conversational skills earned him the name “Little Man” long before he was out of diapers.

Despite Little Man’s advanced verbal skills as a toddler, he struggled in school from the start. He absolutely hated going. He refused to read and had extreme difficulty writing. We hired tutors and arranged for him to receive “extra help” at the parochial school he attended. He still continued to struggle. One day after school, Little Man ran off the bus with tear-stained cheeks and terror in his eyes. He shrieked, “He said he was going to kill me!”

We quickly learned that Tim, a student with whom Little Man was friendly, had joked with him, “Aw, man. I am going to kill you for taking the window seat.”

It was undoubtedly odd. We initially chalked it up to Little Man overreacting. After that day though, there were similar incidents at home, at school and around the neighborhood. It became obvious there was more going on with Little Man than we realized. Several months, many doctor visits and thousands of dollars later, we sat in the office of Dr. Beth Potashkin, a counselor in Scotch Plains. “Dr. Beth” was reviewing the report Johns Hopkins University’s doctors had prepared after evaluating Little Man for a full two days.

“Your son has extreme difficulty understanding nonverbal communication,” she said. “He also has other learning disabilities that severely affect his visual perception, his ability to read and write, and how quickly he can process certain kinds of information.”

Panic set in and I stopped breathing. The sound of Dr. Beth’s words dragged out in slow motion as she explained the impact these disabilities would have on Little Man’s education and the rest of his life. When I recovered enough to tune back in and decipher Dr. Beth’s words, I heard, “All that aside, they found your son is smarter than 99.9 percent of people in the area of verbal intelligence.”

Dr. Beth appropriately paused, expecting some kind of reaction. There was none. We sat stunned in silence. It was one of the rare moments in my life when I was rendered speechless. While the words wouldn’t came out, my mind was screaming What does this mean? As if she could hear my mind-scream, Dr. Beth continued, “You’re son is a ‘2E’kid…he is ‘twice exceptional.’ He is profoundly gifted and he is learning disabled. The school is going to have to accommodate his disabilities and gifts, especially in how they communicate with him, and pace teaching. Sometimes teachers will need to slow down…sometimes they will need to speed up and skip him forward a few grades in the subjects of his giftedness. It’s pretty complicated to teach 2Es. Little Man definitely is going to need an IEP.”

www.istockphoto.com

Seeing our confused faces, Dr. Beth explained, “An Individual Educational Plan.”

And that’s how the journey for Little Man’s special education began. Many, many mistakes were made along the way.

Knowing what I know now, and if finances permit, I strongly recommend you retain a special education lawyer, or consult with one before you start the process. Since I am a lawyer, I represented our family through the classification and IEP process. I know, I know. I was a fool to disregard the wise adage, “A lawyer who represents himself has a fool for a client.”

If you research special education rights on the web, you will likely come up with some variation of this paragraph:

Public schools are required to provide a “free and appropriate public education” (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE) to children who are eligible for special education…To be eligible for special education, a student must: (1) have 1 or more disabilities in specific disability eligibility categories; (2) Which adversely affect(s) educational performance; and (3) For which the student needs special education and related services.

Now, practically speaking, what does that mean for our child in the classroom? I have absolutely no idea. Much of the law I read did zero to prepare me for navigating the process. Those head-spinning special-education acronyms and jargon did not teach me how I could best advocate for Little Man. What did help was understanding what the school must do; what it could do; and what it could not do.

www.istockphoto.com

Lessons Learned

Lesson #1: Do not expect the school to tell you what the musts, coulds and could nots are. It will not happen. Of course, it is in your child’s interest to have a good relationship with the school and work together collaboratively. Just realize that, although a school must give parents a parental rights information booklet, it is not required to educate you on every step of the process. Consequently, when I finally recognized our school was not going to hold my hand through the process, I became much more effective in advocating for Little Man.

Lesson #2: You will never know everything there is to know about special education. You will be the most knowledgeable expert at the table on the most important subject: Your Child. No teacher, educational consultant or school psychologist will know more about your child than you. Don’t shy away from making requests, asking for information or voicing disagreement.

Lesson #3: A doctor’s note—or private educational evaluation stating that special education services are necessary—does not guarantee that your child becomes eligible for special education. Nor will it enable you to skip the evaluation process. These recommendations, however, often provide satisfactory documentation to the school that an evaluation to determine eligibility for special education is warranted. And, since the school can decline to evaluate your child, those recommendations may prove invaluable.

Lesson #4: An Individual Evaluation Plan (IEP) should specify the testing, evaluations and data collected to properly evaluate your child. At a minimum, the school’s evaluation will include parent and teacher interviews, a summary of your child’s educational and health history, classroom observations and other assessments, depending on the suspected learning disability. If it’s feasible, invest in a private evaluation; it is money well spent. Private evaluations usually are more thorough and targeted. Optimally, the final evaluation should identify your child’s intellectual ability in all areas; strengths and weaknesses; learning style and preferences; academic knowledge; and potential environmental barriers to learning. The evaluation should include recommendations for the IEP and give parents the knowledge needed to make specific requests of the school, which, without the private evaluation, might not otherwise be proposed.

Lesson #5: Closely monitor the IEP. It is a legally binding contract between the school and parents, acting on behalf of their child. It sets forth what the school specifically is required to do to appropriately meet your child’s unique educational needs. Even though the school is required to follow the IEP, there could be times the school won’t do so. Sometimes it’s because staff are unaware of the IEP’s requirements, or there is a shortage of staff or resources to implement the IEP. Stay vigilant and monitor if the IEP is being followed. Check with your child and his or her teachers to confirm that the IEP’s accommodations, modifications and/or therapies are being implemented. Make sure appropriately qualified staff are providing services with the frequency stated in the IEP.

Lesson #6: Do not settle for an inappropriate education. There are occasions when a school district is unable to provide an appropriate education to a student who requires special education. In these cases, parents or the school may request to “place” the student in another public school outside of the district—or send the student to a private school. In either case, the school will pay the tuition and transportation costs. Before the IEP is developed, find out what the educational capabilities are of your local school district and of other public and private schools in the area.

A Custom Fit

There is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all approach to teaching kids with learning differences. How our brains take in, process and retrieve information affects how we learn. At a recent meeting of parents of children with learning disabilities, Kathy Russo, a Westfield based educational consultant and former director of a special education school in New Jersey, asked, “Do we learn best by hearing, seeing, touching or through experiencing?”

“Differentiated instruction is a highly individualized teaching approach that meets students where they are,” Russo explains. “Teaching is tailored to the individual student’s current knowledge, strengths, weaknesses and learning preferences. Differentiated instruction has proven remarkably effective at preventing students from disappearing into the cracks at school.”

Public schools are required to provide differentiated instruction to disabled students based on FAPE requirements that are individualized to a specific child and designed to meet the child’s unique educational needs. The requirement is to provide a “free and appropriate education” (FAPE) that is individualized to a specific child and designed to meet the child’s unique educational needs.

However, as noted earlier, the possibility of public schools to provide differentiated instruction is easier said than done. That’s because public schools have to balance providing an appropriate, individualized education that is designed to meet a student’s unique educational needs with the requirement to educate disabled students in the “least restrictive environment” (i.e., a regular classroom with nondisabled peers) “to the maximum extent appropriate.” So in school districts that have small class sizes, providing differentiated instruction to disabled students while in general education classes is manageable. Faculty members are able to provide individualized attention while also educating nondisabled students.

Unfortunately, most school districts have class sizes ranging from 20 to 30 or more students. Providing true differentiated instruction in the face of these numbers can be problematic. As a result, there is increasing pressure on public schools to place students in private special education schools, at no cost to the parents. Before parents can expect a private school placement, they must demonstrate that they have given their local school district a chance to provide the appropriate support. If the core team group of the general education teacher, special education teacher and child study team members (e.g. school psychologist, learning disabilities teaching consultant, school social worker) agree with the parents, and a private school placement is warranted, parents then have to figure out which schools are appropriate for their child. And, with more than 150 special education schools in the state, finding the right school can be a rather daunting task.

Among the New Jersey schools that offer innovative programs for kids with learning differences are The Calais School, Winston Preparatory School and The Jayne S. Carmody School. Each takes a unique approach to differential education.

Founded nearly a half-century ago, The Calais School, in Whippany, serves students in grades Pre-K through 12 who have language and nonlanguage-based learning disabilities. Approved as a special education school by the New Jersey Department of Education, Calais actually works with public school districts throughout the state. It is one of the few places in the country that offers a gifted and talented program to learning disabled students. The school’s Twice Exceptional program uses differentiated instruction to build on students’ gifts, while supporting their learning differences. The New Jersey School Boards Association recently awarded Calais an Innovation in Education Award for the Twice Exceptional program.

Winston Prep was the first high school in New York City specifically devoted to students with learning disabilities. A year ago, it opened a New Jersey campus, also in Whippany. It serves students in grades 6 through 12 who have dyslexia, executive functioning and nonverbal learning disabilities. Students are grouped according to their learning needs, not by grade level. Winston Prep’s differential education approach is rooted in its “continuous feedback system” and Focus Program. Students meet every day with their counselors to discuss their academic progress. The school’s faculty convenes weekly. Based on the continuous feedback provided, IEPs are adjusted as needed.

The Jayne S. Carmody School, which opened this September, was originally conceived in 2007 as a “school within a school” by The Rumson Country Day School. The goal was to keep families together when one sibling had a language-based learning difference. A small number of academically talented students received the school’s exemplary education while benefitting from equally exceptional specialized instruction for their learning disabilities. This inclusive approach, unique among the state’s independent schools, convinced RCDS to expand the physical space and specialized faculty devoted to these students in 2015. This has enabled the Carmody School to accept more mission-fit students, who attend classes with their grade-level peers for all nonlanguage-based subjects, and follow educational plans based upon each child’s unique abilities and strengths. “We are ‘threading the needle’ in terms of the students we’re accepting for the expanded program,” says RCDS Admissions Director Kevin Nicholas. “Students must be an appropriate fit from an academic and behavioral standpoint, because we know those are the children who will thrive at the Carmody School. Unfortunately, that means we’ve had to turn some prospective families away.”

In terms of the bigger picture, parochial (or other faith-affiliated) schools in New Jersey also are an important part of the differential learning landscape. However, because they do not receive state funds and resources, they tend to have a more narrow focus—typically on students who are likely to succeed within the parameters of the programs they have created. Roselle Catholic High Catholic High School has one teacher and one aide who are devoted to students with learning differences. They are provided by the Union County Educational Services Commission. “At the beginning of the year we make sure that teachers read the confidential file on a child’s learning style and work with the guidance department and special education people to accommodate them,” says Martha Konczal, Assistant Principal of Academics. “We try to teach kids what it means to live with a mind that works differently in certain situations, and help them find different ways to make learning work for them.”

Depending on the student and his or her particular needs, many of the state’s top private schools may also offer a good fit. For example, the 133-year-old Wardlaw-Hartridge School in Edison has been supporting differential learning as part of its teaching culture longer than there has been a vocabulary to describe it. “This is a small school where you get to know your students very well, very quickly,” says Maggie Granados, the head of the middle and lower schools, and also Dean of Studies for Pre-K through 12. “So we’ve always been able, within a selective admissions environment, to accommodate different learning styles. That comes from encouraging teachers to ‘recalibrate’ for each student, to alter the format so that a student has a greater sense of engagement in the classroom—whether it’s a high-achieving learner or a struggling one.”

It’s Been Hard

Many lessons learned, and three years later, we continue to march on advocating for Little Man. Many tears have been shed along the journey. It’s been particularly life-changing for our family. We moved an hour away from friends and family to be in a town that was among the highest-rated suburban school districts in the state. The move added 90 minutes to my husband’s commute. I declined career opportunities I had long pursued during the 18-plus years I actively practiced law. Almost every day, I would think or say aloud, “I can’t wait until Little Man is classified so it can be over.” That soon became, “I’ll be so relieved when he has his IEP so it can finally end.” That later evolved into, “As soon as Little Man has the right teachers or the right doctors, it will be okay.”

I kept waiting for it to be over.

One day, it dawned on me how selfish this thinking was. It’s never going to be “over” for Little Man. He’ll be balancing his challenges and gifts for the rest of life. And no matter how many hurdles we clear for Little Man, our family is not going to cross over some imaginary finish line to the life without worry that I invented in my mind. Once I let go of this idea, I think it was the first time I started breathing since that day in Dr. Beth’s office. And while I continue to advocate for Little Man every bit as hard as I always have, I stopped putting life on hold.

Lesson #7 turned out to be by far the most profound one I learned on this journey: I had to stop surrounding Little Man in bubble-wrap. My maternal shield was not protecting Little Man from the world. It only hid him from it. My well-intended protective instinct ended up interfering with Little Man learning how to get through the rainy days. It kept him from enjoying the sunny ones, too. Ever since, I have made a conscious effort to resist the temptation to search out and diffuse potential landmines in Little Man’s world. I have moved the hyper-vigilant Momster that lurks within me to on-call status.

And now, in a peace that has emerged from acceptance, I marvel at the beautiful wonders of our intriguingly complex, brilliant and kind little boy, knowing that one day—much sooner than we will be ready for it—he will no longer be our Little Man. He will be a man. An extraordinary man. Of that, I have no doubt.

Editor’s Note: Trinitas Children’s Therapy Services provides related services supporting students in 10 counties and more than 40 school districts and private special education schools with occupational, physical and speech language therapy services. TCTS is also a resource for independent evaluations (mentioned earlier in this story). For information on evaluations, call (973) 218–6394 or email info@childtherapynj.com.

Kids…They Swallow the Darndest Things

Few moments are more frightening to a parent than the realization that their child may be choking on, or have swallowed, a foreign object. Sadly, every five days a child in the U.S. dies in a choking incident, almost always involving food, toys or coins. Choking is especially common in children 4 years old and younger. Thankfully, the vast majority of incidents are resolved by vigilant parents and quick-thinking doctors and nurses. As an ER physician, you never know what you’ll find when you ask a young patient to “open wide.”

Sir Isaac Newton is famous for saying, “What goes up, must come down.” Is the opposite true?

Although I make no claim to being a world-famous physicist, I can tell you with some authority that, no, the opposite is rarely true. Once something goes down a kid’s throat, it may require a visit to your local ER.

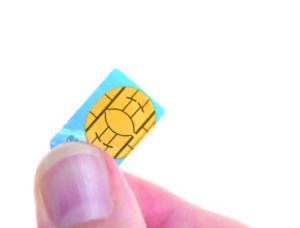

Is coughing and wheezing in a baby or toddler usually an upper respiratory issue—such as a cold or asthma—or should parents pay closer attention?

You should pay closer attention, because the problem could be the result of an ingested foreign body. Just because a child isn’t choking per se, it doesn’t mean something’s not stuck down there. For example, one morning, a father rushed his 18-month-old son into our ER coughing and wheezing. I took the child from the dad’s arms and attempted to lay him flat on a stretcher. The child refused to lay flat. He would only sit upright. I tried again.

The child began to choke and cough. The dad said, “See that? He is coughing and wheezing again.” A quick examination of the child’s eyes, ears and nose was normal.

So what was the issue?

While a nurse held the child’s head steady, I depressed his tongue and there it was: a tiny gold-colored, rectangular object lodged in his airway. We sat the child upright and I used alligator-forceps to extract the item. It was a SIM card from his father’s cell phone. Only then did the father put it all together—he realized that his son had been teething and sucking on his cell phone and had accidentally ingested the SIM card. What the father had heard was actually not wheezing. It was stridor, which is an upper-airway obstruction at or above the level of the vocal cords.

www.istockphoto.com

What other objects do you see fairly regularly in the ER?

Ingested foreign bodies come in many different shapes and sizes. Some of the most common include coins, button batteries, regular batteries, small toys that contain magnets, plastic hair beads, crayons, safety pins, paper clips and hairpins. The ingestion of button batteries, which are often lithium batteries, is a true emergency and could be fatal. Button batteries can be found in common items such as watches, small toys, cameras and children’s sound storybooks, among other things.

What’s the procedure involved in dislodging a button battery?

Once a patient has presented to the ER with this type of ingestion, the ER doctor must take an x-ray to make certain that it is not in the esophagus. The caustic within the button battery can erode the esophageal wall and cause a severe, life-threatening infection within the thoracic (chest) cavity. The treatment is emergent retrieval of the button battery via an endoscopy, performed by a Gastroenterologist. The main point here is if you think your child has ingested a button battery, do not wait. Bring your child to the ER immediately for evaluation.

What happens when a child actually swallows a small object and it passes through the esophagus and into the stomach?

The response depends on the object. An 8-year-old girl presented to the ER one evening on the night of her First Holy Communion. She had gone to bed and then, a half-hour later, ran to her mother in fear stating, “I don’t want you to yell at me, but I think I lost my St. Elizabeth metal that Uncle Joe gave me today for my Communion! I have the chain, but I can’t find the medal.” After a thorough search of the bed and room, her parents grew suspicious and feared that she had in fact swallowed the medal by accident, but she was afraid to admit the truth.

Was that the case?

It was. After an x-ray of the child’s chest and abdomen, I discovered that the medal had already passed through the esophagus and into the stomach.

Did she confess—no pun intended?

Yes, in private, I again asked the child what had happened. She spilled the beans: “I was hanging upside down off the side of my bed, flipping the medal in and out of my mouth with my tongue…and then it came off of the chain! I got scared and accidentally swallowed it when I tried to get back up onto my bed. Please don’t tell Mama!”

www.istockphoto.com

Did it pass through her system?

Yes. In general, once coins, medallions, etc., have moved beyond the esophagus, they will pass freely through the bowels. If a child has no symptoms after such an incident, a follow-up x-ray 2-3 days later can show us whether or not the coin has passed through the bowels. If a child experiences vomiting or abdominal pain, however, a repeat examination is needed, complete with x-ray. If the object is stuck, then it may have to be removed.

ALSO…

People with specific medical needs should have a wristband that would alert doctors and nurses of that special need. It might even save a life.

—Rita B.

We use different color-coded wristbands for certain (but not all) patients, Rita. It’s actually part of the Critical Care Committee’s playbook at Trinitas. Expanding this to include a wider range of conditions is something we are always looking at.

—John D’Angelo, DO

Editor’s Note: John D’Angelo, DO, is the Chairman of Emergency Medicine at Trinitas Regional Medical Center. He has been instrumental in introducing key emergency medical protocols at Trinitas, including the life-saving Code STemi, which significantly reduces the amount of time it takes for cardiac patients to move from the emergency setting to the cardiac catheterization lab for treatment.

Do you have a hot topic for Dr. D’Angelo and his Trinitas ER team? Submit your questions to AskDrD@edgemagonline.com

The stigma attached to Alzheimer’s—and a dearth of clinical trial volunteers—may be slowing the development of a breakthrough drug.

When I was doing my post-doctoral fellowship, I was in the room with a neurologist who gave a patient an Alzheimer’s diagnosis and then left. I think the family forgot I was still in the room. The man turned to his wife and said, “We really need smarter people working on this problem.”

Well, in the two-plus decades since, there have been a lot of smart people working on it, and progress has been made. New drugs have come on the market: Cognex in 1993, Aricept in 1996, Exelon in 2000, Razadyne in 2001, and Namenda in 2003. In 2011, for the first time in 27 years, a revision of the initially proposed 1986 consensus criteria for Alzheimer’s Disease were established, which incorporate all of the data and technological and clinical advances that have been amassed over the past several decades of research. Since we now know that people suffering from Alzheimer’s have probably had plaques and tangles developing in their brains for decades, the emphasis on early intervention is greater than ever.

We are currently in a better position to identify pre-symptomatic patients so that, if we had a disease-modifying medication, we could catch people early and possibly prevent the disease from progressing. There are a lot of companies looking for that breakthrough Alzheimer’s drug, which is why clinical trials are so important.

Ironically, the biggest obstacle right now in finding a cure for Alzheimer’s Disease may be the lack of participants in the studies being run on these new drugs and therapies.

Pharmaceutical companies are way behind in recruiting volunteers. Timelines for enrolling subjects are usually not met. This means critical data is coming out too slowly. We have not had an investigational Alzheimer’s drug get past Phase III in years.

WHO CAN PARTICIPATE?

The profile of a trial participant ranges from someone with cognitive impairment or concern to individuals who have received an Alzheimer’s diagnosis but are otherwise healthy. About half of the participants in the trials we run come through our clinic, the Cognitive and Research Center of New Jersey; these are people with whom we have already established trust and rapport. Others are referred by groups of neurologists, internists and gerontologists. We also get participants as a result of the public outreach I do personally. I am a big advocate of Alzheimer’s education and do a lot of speaking at churches, synagogues, senior centers, and other venues.

So why the lack of participants? Some are afraid that they’re agreeing to be “guinea pigs” for drug companies. That’s a valid objection, but people with this objection may not appreciate that these trials are very highly regulated by the government. It is very hard for a drug company to start a clinical trial. The FDA and other regulatory agencies have to be convinced that the potential benefits outweigh any risk; patient safety is concern number-one. Each trial has a set of strict criteria, and always errs on the side of safety.

www.istockphoto.com

There are other factors that make it difficult for clinics to find an adequate number of volunteers. Alzheimer’s trials have a high rate of screening failure. Even here—where we are highly specialized—the screening failure rate can range up to 50% after we’ve done urine, blood and EKG testing. Sometimes, people don’t meet criteria for a study because of preexisting medical conditions or medication regimens. There are always lists of medications that can’t be taken with the drug that’s being tested, and the patient can’t stop taking a particular medication.

www.istockphoto.com

Something else that impacts Alzheimer’s trials is that there will be a “study partner” involved. This is someone who knows the patient well and is in close enough proximity to acknowledge that the medication is being taken, and who can generate qualitative information, such as new symptoms, the level of caretaker burden, the patient’s mood and daily living skills—and just answering the question How are they doing? This is usually an immediate family member, but can also be a close friend. Without a committed study partner, it is unlikely an individual would be able to participate in an Alzheimer’s (or even a cognitive impairment) trial.

Finally, there is the stigma associated with Alzheimer’s, which I hope is changing. People think it’s a mental illness instead of a progressive medical disease. That could well be at the root of the recruiting problem pharmaceutical companies are experiencing in their trials. My perception is that a lot of people delay getting a diagnosis, mostly out of fear or perhaps denial. Incredibly, in fact, more than half the people who have Alzheimer’s never actually receive a diagnosis—even as they are being prescribed medications such as Aricept.

TRIAL BENEFITS

Among the major benefits of participating in a clinical trial is access to some of the better technology that is being developed. There are a number of procedures a patient’s insurance might not cover, including amyloid PET scans, which are very expensive. Thanks to this technology, we can actually detect microscopic changes in the brain that can give us a more concrete diagnosis.

All of the assessments a patient receives during a study are free. And sometimes there is a stipend for patients and their study partners.

Perhaps the most compelling reason to get involved in an Alzheimer’s study is the fact that people who are in clinical trials do better than people who are not—even those who are in the placebo group. Receiving attention from four or five specialists, talking about your condition, and receiving constant feedback is very therapeutic for the patient and for the study partner. In fact, most people who have completed one trial here want to get right into another.

The length of a clinical trial can vary from months to years. The length of each visit could take 45 minutes or four to five hours depending on what kind of evaluations are being done. Typically the clinic visits are more frequent at the beginning of a trial so that we can establish eligibility and collect baseline measures.

Whether volunteering for a clinical trial is appealing or not, families facing the prospect of a loved one with Alzheimer’s Disease need to take action. This disease is hard to deal with on your own, without support. The longer a family waits for a diagnosis, the sooner they’ll find themselves dealing with things in disaster mode.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Association estimates that 5.3 million Americans suffer from Alzheimer’s, and that number will continue to rise as the Baby Boomers age.

Unfortunately, right now less than half of these individuals are actually being told they have it. They don’t want to hear the diagnosis. So large numbers of patients and their families are suffering through the disease with no help.

They need to be educated to plan for the future and understand changes in behavior, and to prepare for the practical and emotional issues of care they will face. When we conduct our initial neuropsychological evaluations, everyone leaves with a folder containing information about relevant resources. People may be hesitant to use those resources initially, but they are good to have on file. Also, individuals who get linked with resources fare much better than people who put off being evaluated.

www.istockphoto.com

The first step for many patients and their families is to deal with the overwhelming idea that once you have Alzheimer’s, there’s nothing anyone can do. The fact is there are things we can do. And the trials that clinics like ours are conducting hold great promise that soon we’ll be able to do much, much more.

Editor’s Note: Michelle Papka is a neuropsychologist specializing in Alzheimer’s Disease and mild cognitive impairment. For more information log onto thecrcnj.com or email info@thecrcnj.com.

Renal Patients Learning to THRIVE Through Education & Intervention

The best-kept secret in Linden isn’t a chic boutique. It’s not a trendy eatery, nor is it a new after-hours hot spot. According to Joseph McTernan, it’s the Trinitas Renal Services Unit, which has made the difference in countless thousands of lives since opening in 1993.

“Right here in Linden, we offer world-class expertise in both the diagnosis and treatment of renal disease,” says McTernan, Senior Director of Community and Clinical Services for Trinitas Regional Medical Center. “Our renal program has won a national award for excellence in patient care, and our highly qualified physicians and staff boast years of experience. We have won a five-star rating from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which puts us in the top 10 percent of dialysis centers around the country. It’s a designation that affirms the strength of our renal care outcomes.”

Ruby Codjoe, Nurse Manager of the Linden Dialysis Center, Peggy Custode, Renal Clinician at the Dialysis Center at the Williamson Street Campus, and Dr. James Mc Anally, Chair of the Nephrology Division at Trinitas, regularly review patient cases. On a weekly basis, the Linden Center treats up to 90 Chronic Kidney Disease patients while the Williamson Street Renal Dialysis Unit treats up to 75 patients.

How does one measure such a thing? It’s a numbers game, says Dr. James McAnally, Chair of the Division of Nephrology: ER visits, hospital admissions, and infection rates. And the Trinitas numbers are indeed outstanding.

“Our patients require 40 percent fewer emergency department visits than the national average, and 43 percent fewer hospital admissions,” says Dr. McAnally. “Our rate of infection is less than half of the national average.”

Besides its Linden location, which treats chronic patients, the Renal Services Unit also has a location at the main campus on Williamson Street and another at the New Point campus, both in Elizabeth.

10 STEPS TO RENAL HEALTH

10 STEPS TO RENAL HEALTH

- Exercise regularly

- Don’t overuse over-the-counter painkillers or NSAIDs

- Control your weight

- Get an annual physical

- Follow a healthy diet

- Know your family’s medical history

- Monitor blood pressure & cholesterol

- Don’t smoke or abuse alcohol

- Talk to your doctor about getting tested if you’re at risk for chronic kidney disease

- Learn about kidney disease

“If you have high blood pressure, diabetes, a family history of kidney failure, or are over age 60, the best thing you can do is to get tested for kidney disease annually by a doctor,” Sean Roach, Public Relations Manager for the National Kidney Foundation tells EDGE. “Usually, a urine test is all you need.”

“If you have high blood pressure, diabetes, a family history of kidney failure, or are over age 60, the best thing you can do is to get tested for kidney disease annually by a doctor,” Sean Roach, Public Relations Manager for the National Kidney Foundation tells EDGE. “Usually, a urine test is all you need.”

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is found in 26 million adults in the United States. The most common causes of CKD are diabetes and hypertension. Data shows that African Americans and Hispanics are disproportionately effected.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is found in 26 million adults in the United States. The most common causes of CKD are diabetes and hypertension. Data shows that African Americans and Hispanics are disproportionately effected.

So, what’s the plan of attack to diagnose and treat all those who have chronic kidney disease?

www.istockphoto.com

INTERVENTION & EDUCATION

“Education is a big part of what we do,” Dr. McAnally points out. “We teach patients how to take the best care of themselves. We have them meet with nutritionists and other professionals to make every day the best day possible.”

The first step on this journey toward living the best days possible is The High Risk-Intervention Via Education (THRIVE) Program at Trinitas, which Dr. Mc Anally founded more than 20 years ago. It addresses CKD in its early stages. Dr. Mc Anally explains: “The goal of the THRIVE program is not only to educate and to empower patients regarding CKD and its various treatment options, but more importantly to develop strategies to slow the progression of CKD.

With the support of the National Kidney Foundation, Trinitas has conducted annual screenings to help community members become aware of the likelihood that they may develop CKD based on hereditary or lifestyle factors. “Through our efforts, we have reached more than 500 people who have participated in our Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP),” explains Peggy Custode, Renal Clinician.

The THRIVE program is based on the five “E’s” of rehabilitation:

- Encouragement. The THRIVE team gives patients with impending kidney failure the encouragement they need to adopt a positive attitude toward rehabilitation.

- Education. The THRIVE team gives patients and their families the education they need to handle the sometimes profound life changes associated with chronic illness, including coping strategies for successful adaptation.

- Exercise. Gradual decline in muscle strength and endurance is a result of inactivity. THRIVE patients are encouraged and counseled about exercise. There are many levels of activity to fit varying degrees of functional ability, from vigorous workouts for the otherwise healthy patient to stretching exercises for the chairbound.

- Employment Referrals. Occasionally there is a need to alter the work environment to address healthcare needs. The THRIVE staff assists patients in meeting these needs.

- Evaluation. Identifying patients early and educating them about kidney disease—and how to comply with a treatment plan—enables them to manage their own health, which will improve outcomes.

These 5 E’s of rehabilitation work. As a result of the THRIVE program, most patients begin renal therapy electively in an outpatient setting. “Such therapy has been associated with decreased morbidity, decreased mortality and lower costs overall,” reveals Dr. Mc Anally.

“Our mission isn’t simply helping patients survive,” McTernan adds. “It’s about showing them how to thrive.”

DIABETES & KIDNEY DISEASE

How prevalent is kidney disease? Sean Roach of the National Kidney Foundation says that 26 million American adults—nearly one in 10—have kidney disease. “And, most don’t know it,” he says. “That figure is projected to climb to 14.4% in 2020, and 16.7% in 2030.”

Dr. McAnally says the current diabetes epidemic is largely to blame for the increasing number of kidney disease cases. Diabetes is one of America’s leading killers, as well as the number-one cause of kidney failure. Also, signs and symptoms of kidney disease are often nonspecific. That means they can be caused by other illnesses. And because kidneys are highly adaptable and able to compensate for lost function, signs and symptoms may not appear until irreversible damage has occurred.

“Dr. Mc Anally’s professional career has been devoted to nephrology and to teaching patients how to manage their kidney disease,” says Joe Mc Ternan. “He has encouraged people who have hypertension or diabetes to take responsibility for their renal care before they experience significant kidney failure.”

Toy Story 0.5 (aka Surviving the 1960s)

Once upon a time, in a foreign country called the 1960s, there were no au pairs, soccer moms or helicopter parents. City kids rode public buses to school and back. In the suburbs, children roamed neighborhoods like packs of feral animals. Uncle Frank might slip 12-year-old nieces and nephews fireworks and cigarettes and a gulp of his beer every now and then—and make them promise not to tell mom and dad (or Aunt Shirley). Granddad would take you out in his Pontiac Bonneville at dawn on Sunday morning and teach you to drive on the Pulaski Skyway and the New Jersey Turnpike. Believe it or not.

Upper Case Editorial Services

If, like me, you were born in the United States between 1954 and 1964, you belong to an exclusive demographic: The Late Baby Boomers. We were born smack-dab in the middle of what economists have dubbed The Thirty Glorious Years, an epoch of prosperity and abundance unparalleled in human history. We were the progeny of the can-do New Frontier. We were expected to grow up fast and, in large part, do it on our own. More and more of us were children of divorce, with two or more working parents. The term invented for us was latchkey kids. A close friend who’s a bit older and wiser observed that a lot of us suffered from benign neglect. He maintains that we didn’t get enough time with our folks, who were always working. And that they couldn’t wait until we were old enough to start working, too.

www.istockphoto.com

So many of the toys produced and marketed to us in the 1960s, and that our parents bought for us, are looked upon a half-century later with horror and disbelief. If you’re a Late Baby Boomer, however, you also harbor a certain nostalgia for all those hot, sharp and toxic playthings. I think this is because they reflected the cultural philosophy of our parents. Life is full of risks, kid—here’s some dangerous stuff to get you used to taking them. And don’t come crying to us unless you need stitches.

Mattel, Inc.

CALIFORNIA DREAMIN’

I was born in San Francisco in 1960 and was a toddler in Santa Monica. My parents relocated back to Manhattan before I turned three. On weekends, I’d kick around my grandfather’s car dealership in Jersey City. In March of 1968, my mom put me on an American Airlines flight from JFK to LAX, alone, to meet up with my copywriter dad, who was shooting a series of KOOL cigarette ads in Southern California. The stewardesses pampered me like a lost puppy.

For an eight-year-old kid who only knew the gray, gritty streets and harsh winters of New York, Los Angeles in 1968 was like paradise. Perfect concrete streets, fantastic googie architecture, Hollywood studio backlots, dayglo and hippies and surf music and Kustom Kars. And the Valhalla of all 1960s kids: the Magic Kingdom of Disneyland in Anaheim. On the way to D-Land, on the I-5 Golden State Freeway, we passed through Hawthorne. Right there along the side of the freeway was Disneyland’s not-so-distant cousin, the Magic Factory of Mattel Toys, where just about everything cool—from Hot Wheels to Creepy Crawlers—were actually made.

In San Gabriel, five minutes off the I-10 Santa Monica Freeway, just about everything else that was cool was made at the Wham-O factory: Hula Hoops, Frisbees, Super Balls, Slip and Slides, Instant Elastic Bubble Plastic, Silly String and Silly Slime. If it could be made from some potentially toxic new plastic polymer, you could be sure that Wham-O would serve it up.

Think about it. Pretty much all of today’s extreme sports were birthed by us Late Baby Boomers. We built jumps for our Sting-Rays and Tarzan swings at lake shores. We snuck into neighbors’ backyards to skateboard in their empty swimming pools. Cowboys & Indians seemed quaint and outdated to us. We played war…how much more “extreme” can you get?

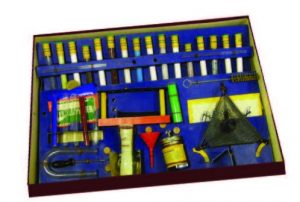

Not that we had many options. Growing up in the 1960s, there were no video games, just a black & white screen (only the seriously affluent had color TVs) with a handful of channels that actually ran children’s programming. Most of the shows I watched had product tie-ins with toy companies like Marx, Transogram, Mattel, Ideal and Topper. Most of the action toys—particularly for boys—launched projectiles like rockets or grenades, using springs or water/air pressure. A few in particular that stick in my head are the Fireball XL5 Space City Playset, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Napoleon Solo gun, and the James Bond 007 Attaché Case, which shot a hard plastic bullet with the press of a hidden button in the handle.

I grew up a Junior Mad Man. My dad was an advertising copywriter, my mom an account executive and stepdad an art director. Basically, I was hardwired to consume from the cradle. Television was the gift that never stopped giving. It brought the money into the house, and then showed what you could exchange for it. For me, it was invariably the latest dangerous, worthless plastic piece of junk as seen on TV. Surviving examples are still dangerous and toxic, but the ones in mint-condition are far from worthless. Spend five minutes on eBay and you’ll see.

It occurs to me that the much-maligned Helicopter Parent might be the indirect product of these toys. Maybe these are the boys who were bludgeoned or terrorized or used as guinea pigs by their older siblings. Or the girls who scorched themselves cooking cupcakes with 200-watt lightbulbs. In one generation, the protection pendulum swung from one extreme to the other.

I look back at the halcyon days of irresponsible parenting and no longer ask What were they thinking? I’m halfway through my 50s now and I get it. All is forgiven. The folks who designed and marketed the toys we played with, however, are another matter entirely. I don’t think I’ll ever understand how some of these products found their way on to store shelves. Here then are my Unlucky 13:

I NEVER INHALED

Which is a good thing, because the Gilbert Glass Blowing Kit—manufactured until the early 1960s and available at garage sales for another decade—was permanent lung damage waiting to happen. Lest you forget, molten glass has a temperature of 1000º F. A sure litmus test to see if your parents were cheapskates (or simply out to maim you) was whether or not they’d cough up the additional coin for goggles, a pair of welder’s gloves, and an asbestos table board. Because, you guessed it, safety equipment was “sold separately.”

Upper Case Editorial Services

BIG BANG

Introduced in the 1940s and manufactured until the early 1970s, Chemistry Sets put the boom in the Baby Boom. Blowing yourself up or poisoning yourself was no problem thanks to entry-level basics Potassium Permanganate and Ammonium Nitrate, Tannic Acid and Sodium Ferrocyanide. Bomb- and poison-making made simple and fun! Refills available. Some of the most popular and dramatic things a kid could do with a deluxe set was to perform magic tricks, like turning water (aqueous solution of sodium carbonate and bicarbonate) into wine (adding phenolphthalein), then into milk (adding barium chloride), and then into beer (adding potassium dichromate and hydrochloric acid). The grand finale? Persuading your “assistant” (younger sibling, idiot neighbor) to drink it.

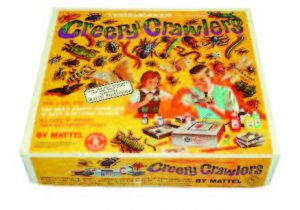

BURN NOTICE

Why squander precious nickels and dimes buying rubber bugs out of gumball machines when you could make your own? The economics of Mattel’s

Mattel, Inc.

Creepy Crawlers seemed obvious to anyone with a first-grade education. And that’s about how old kids were when their parents handed them a box containing a 300ºF hot plate, cast metal molds and a semi-liquid “non-toxic” substance in plastic squeeze bottles that everyone called “goop.” Creepy Crawlers hit the market in 1965 and were incredibly popular. Unfortunately, they weren’t edible. So in 1968, Mattel unveiled Incredible Edibles—featuring the same equipment along with semi-liquid candy called Gobble-Degoop in six colors and flavors: root beer, cherry, licorice, butterscotch, cinnamon, and mint. My friends and I got some very nasty burns and blisters from these child scar-makers. We’d become impatient for the bugs to finish cooking solid, and get splattered with super-hot molten plastic and gummy sauce trying to pry them out of the burning-hot molds with tweezers and sewing needles. On the plus side, visiting the emergency room was very educational.

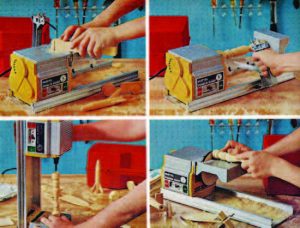

SHOP TIL YOU DROP

Sand off your fingerprints! Lose a pinky! Drill-press the cat! The Mattel

Mattel, Inc.

Power Shop, introduced in 1964, offered dozens of possible projects and hours of fun. All of the big, noisy machines those lucky big kids were allowed to use in junior high were now within your seven-year-old grasp (at least until you started severing tendons).

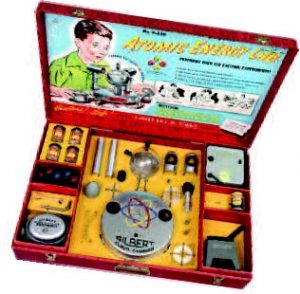

HONORABLE MENTION

For two years in the early 1950s, parents could purchase at the then-astronomical cost of $50 the

A.C. Gilbert Company

Gilbert Model #U-238 Atomic Energy Lab. The sell copy says it all:

- Most modern scientific set ever created!

- See paths of alpha particles speeding at 12,000 miles per second!

- Watch actual atomic disintegration—right before your eyes!

- Prospect for Uranium with Geiger-Mueller Counter!

- 10,000 Dollar Reward: That’s what the United States Government will pay to anyone who discovers deposits of Uranium ore!

- Full details in the book Prospecting for Uranium, packed with this Atomic Energy Lab.

- Includes: Geiger-Muller Counter, Wilson Cloud Chamber, Spinthariscope, Electroscope, Nuclear Spheres, Alpha Beta and Gamma radiation sources, radioactive ores.

- Three illustrated books: Prospecting for Uranium, How Dagwood Splits the Atom, Gilbert Atomic Energy Instruction Book

- All Samples of Radioactive Materials are Completely Harmless!

I can’t imagine why this was pulled off the market. By the way, if you want a mint-condition original today, get out your gold coin. They can sell for thousands at auction.

DIGITAL DIVIDE

Say what you will about Mattel’s electric-powered toys. At least they were certified by Underwriters’ Laboratories. No such luck with Jig Saw Junior, which hit the market in 1958 courtesy of Burgess Industries, with this bit of marketing gold: “It will vibrate well enough to cut balsa or other thin soft woods without taking off your child’s finger.” You can practically hear Dan Aykroyd’s sleazy Irwin Mainway character pitching this product on SNL between Bag o’ Glass and Johnny Human Torch.

BLAST FROM THE PAST

Water Rockets were our gateway drug to the Space Race. For a couple of bucks, every child could do his or her part to beat the Russkies to the moon—and get a refreshing, explosive splash of water on a hot summer day. So let’s do the Newtonian calculus: Two pounds of air-pressure water sealed in hard plastic, accelerating to a velocity of 40 miles per hour within a few yards. Just what a kid needs to crack the windshield of the family car. Or dent the skull of his nerd cousin Elaine.

Transogram Company, Inc.

WEARABLE WHIPLASH

The

Swing Wing, introduced in 1965, was one of those toys that made absolutely no sense, but how could you not beg your parents for it after seeing those head-twirling kids on the commercial? It was a plastic chin-strapped beanie, with a long weighted cord attached to a pivot on top. It was meant to be a cranium-mounted spin-off of the Hula Hoop. Which translated to permanent neck vertebrae damage and—for the accomplished Swing-Winger—potential paralysis. From Transogram…Where the FUN comes from!

Photo by Santishek

STRING THEORY

The idea was elegant in its stupidity. Klik-Klaks were two hard-plastic spheres attached by thin cords to a central ring, which slipped over your finger. Move your hand up and down at just the right speed, and they crashed together at 12 o’clock and 6 o’clock again and again and again. They were outlawed in schools for noise and safety reasons, but that just made them more alluring, and in the late-60s companies rushed cheaply made competing versions to market with no regard for quality. This led to two basic outcomes: String failure, leading to property damage, or a shattered ball, leading to eye damage.

SLIPPERY SLOPE

Wham-O introduced the Slip and Slide in 1961as the backyard progenitor to the waterslide theme park. It was nothing more than a garden hose attached to a long strip of slick vinyl. Millions were sold before anyone gave a second thought to safety. If you broke a toe on one of the stakes that secured it to the lawn or caught a major raspberry on the driveway because you slid off the end, well…that was your problem. Kids who limped away from these injuries were the lucky ones. Adults who found this toy irresistible relearned much of what they had forgotten from physics class, like “a body in motion tends to stay in motion” (Newton again) even when you run out of Slip and Slide. Eventually, words like “spinal cord injury” and “death” were included in the instruction manual’s safety warnings. A handicapped access icon should have been added, too.

Louis Marx & Co.

NO BRAKES NO STEERING NO PROBLEM

Introduced in 1968, the Krazy Kar from Marx was an ill-conceived kiddy car compounded by a near-total absence of control. Kids sat in a circular plastic frame and propelled themselves using two oversized wheels with handles. Two pivoting shopping-cart wheels at the front and rear ensured kraziness. The children pictured on the packaging seemed blissfully unaware of their fate. Perhaps they lived in a hilltop subdivision or at the end of a steep driveway. Its more-than-passing resemblance to a “krazy” wheelchair should have been a tip-off to parents. And yet, the Krazy Kar has endured, careening back into stores during the 1990s to inure a whole new generation of kids.

TRIGGER HAPPY